Book contents

- Ovarian Stimulation

- Ovarian Stimulation

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Contributors

- About the Editors

- Foreword

- Preface to the first edition

- Preface to the second edition

- Section 1 Mild Forms of Ovarian Stimulation

- Section 2 Ovarian Hyperstimulation for IVF

- Section 3 Difficulties and Complications of Ovarian Stimulation and Implantation

- Section 4 Non-conventional Forms Used during Ovarian Stimulation

- Section 5 Alternatives to Ovarian Hyperstimulation and Delayed Transfer

- Section 6 Procedures before, during, and after Ovarian Stimulation

- Index

- References

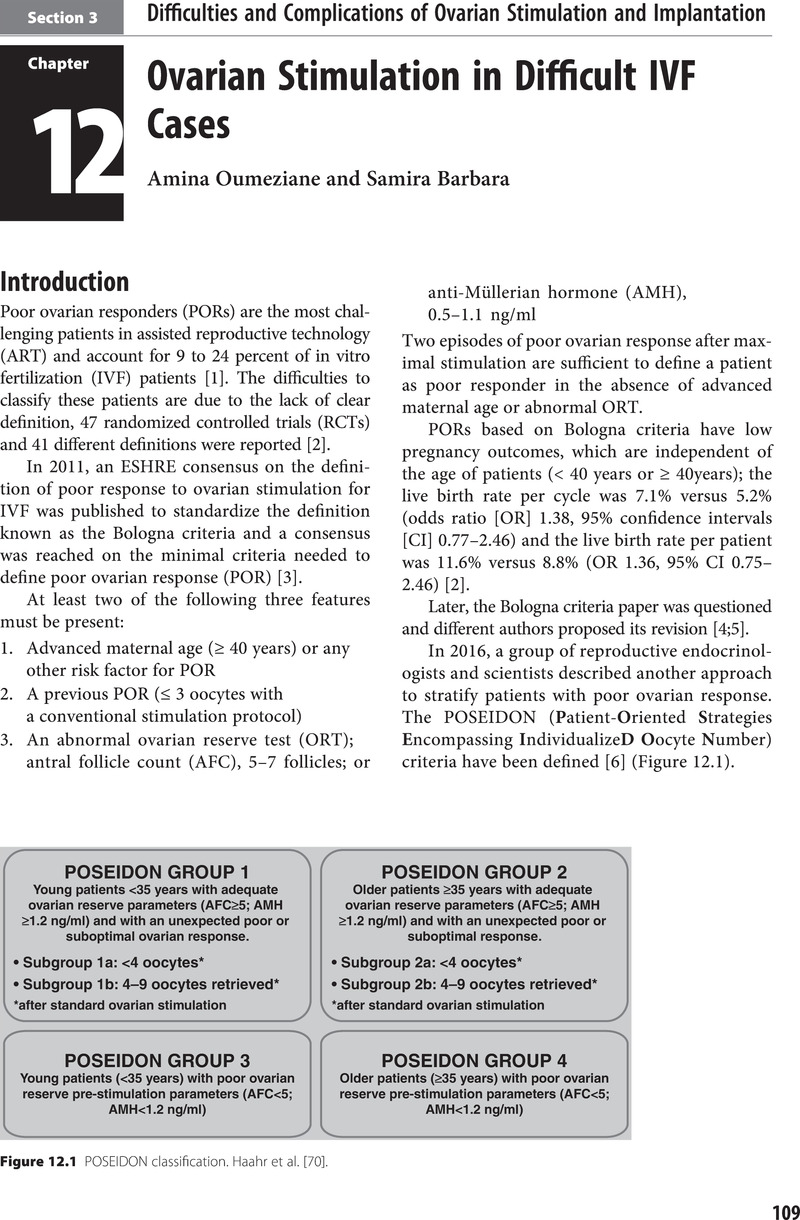

Section 3 - Difficulties and Complications of Ovarian Stimulation and Implantation

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 14 April 2022

- Ovarian Stimulation

- Ovarian Stimulation

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Contributors

- About the Editors

- Foreword

- Preface to the first edition

- Preface to the second edition

- Section 1 Mild Forms of Ovarian Stimulation

- Section 2 Ovarian Hyperstimulation for IVF

- Section 3 Difficulties and Complications of Ovarian Stimulation and Implantation

- Section 4 Non-conventional Forms Used during Ovarian Stimulation

- Section 5 Alternatives to Ovarian Hyperstimulation and Delayed Transfer

- Section 6 Procedures before, during, and after Ovarian Stimulation

- Index

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Ovarian Stimulation , pp. 109 - 188Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2022