Book contents

- Mozart in Vienna

- Mozart in Vienna

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Tables

- Musical Examples

- Acknowledgements

- Notes on Musical Examples

- Abbreviations

- Introduction: Mozart the Performer-Composer in Vienna

- Part I Beginnings, 1781–1782

- Part II Instrumental and Vocal Music, 1782–1786

- Part III The Da Ponte Operas, 1786–1790

- Part IV Instrumental Music, 1786–1790

- Part V Mozart in 1791

- Appendix Mozart’s Decade in Vienna, 1781–1791: A Chronology

- Select Bibliography

- Index of Mozart’s works by Köchel number

- Index of Mozart’s works by genre

- General Index

- References

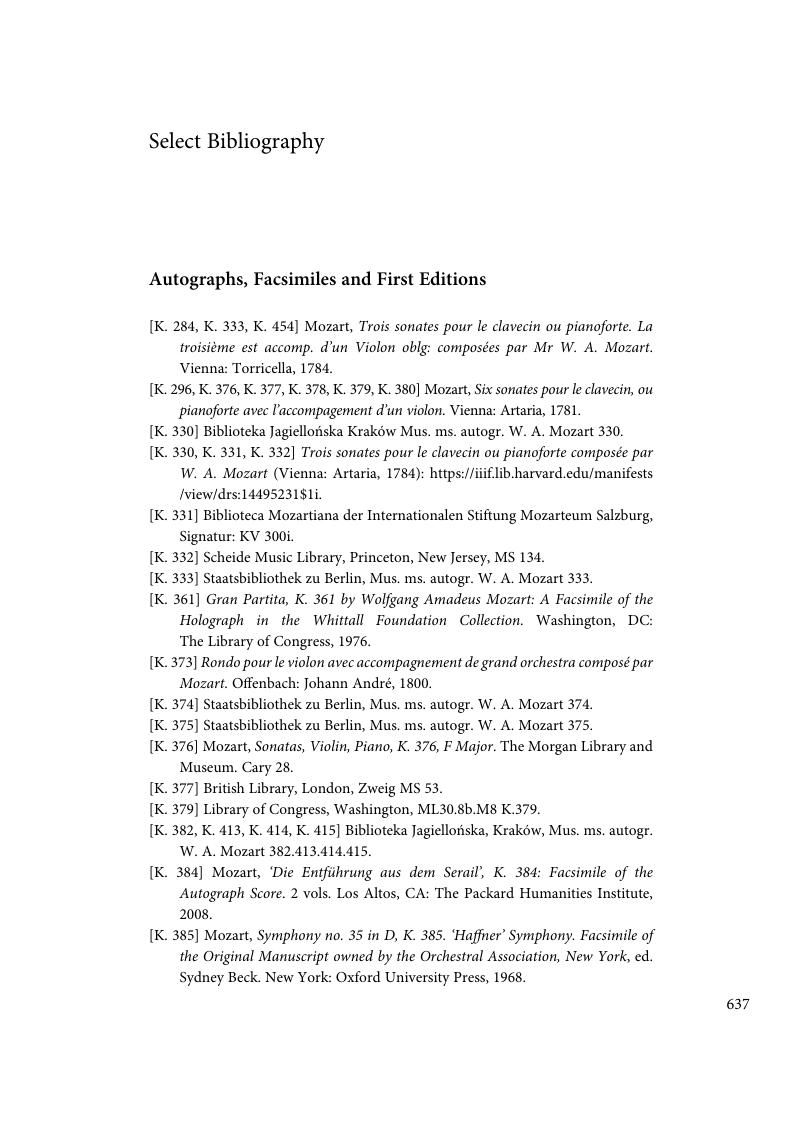

Select Bibliography

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 21 September 2017

- Mozart in Vienna

- Mozart in Vienna

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Tables

- Musical Examples

- Acknowledgements

- Notes on Musical Examples

- Abbreviations

- Introduction: Mozart the Performer-Composer in Vienna

- Part I Beginnings, 1781–1782

- Part II Instrumental and Vocal Music, 1782–1786

- Part III The Da Ponte Operas, 1786–1790

- Part IV Instrumental Music, 1786–1790

- Part V Mozart in 1791

- Appendix Mozart’s Decade in Vienna, 1781–1791: A Chronology

- Select Bibliography

- Index of Mozart’s works by Köchel number

- Index of Mozart’s works by genre

- General Index

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Mozart in ViennaThe Final Decade, pp. 607 - 636Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2017