Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of illustrations

- List of contributors

- Preface

- 1 Introduction

- 2 A single spark

- 3 Quotation songs

- 4 Mao quotations in factional battles and their afterlives

- 5 Translation and internationalism

- 6 Maoism in Tanzania

- 7 Empty symbol

- 8 The influence of Maoism in Peru

- 9 The book that bombed

- 10 Mao and the Albanians

- 11 Partisan legacies and anti-imperialist ambitions

- 12 Badge books and brand books

- 13 Principally contradiction

- 14 By the book

- 15 Conclusion

- Index

- References

6 - Maoism in Tanzania

Material connections and shared imaginaries

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 June 2014

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of illustrations

- List of contributors

- Preface

- 1 Introduction

- 2 A single spark

- 3 Quotation songs

- 4 Mao quotations in factional battles and their afterlives

- 5 Translation and internationalism

- 6 Maoism in Tanzania

- 7 Empty symbol

- 8 The influence of Maoism in Peru

- 9 The book that bombed

- 10 Mao and the Albanians

- 11 Partisan legacies and anti-imperialist ambitions

- 12 Badge books and brand books

- 13 Principally contradiction

- 14 By the book

- 15 Conclusion

- Index

- References

Summary

We stand for self-reliance. We hope for foreign aid but cannot be dependent on it; we depend on our own efforts, on the creative power of the whole army and the entire people.

Self-Reliance and Arduous StruggleIn December 1966, President Julius Nyerere embarked on a six-week tour of half of the regions in the newly independent East African country of Tanzania, which the national press enthusiastically dubbed his “Long March.” During this journey to both major regional centers and remote rural outposts, Nyerere called upon Tanzanians across the countryside to unite in pursuit of the country’s new developmental imperatives: self-reliance and socialism. In a pamphlet published several years earlier, Nyerere had already begun to outline these political principles, introducing the concept of ujamaa, or “familyhood,” into national discourse as the foundation for a proposed program of African socialism. It was not until the conclusion of his “Long March,” however, that Nyerere officially inaugurated the policy of ujamaa that would structure life in Tanzania over the next decade. On February 5, 1967, in a widely publicized manifesto issued in the northern town of Arusha, President Nyerere – popularly known as Mwalimu (Teacher) – announced the ideological contours of a radical approach to national development based upon collective hard work, popular agrarian transformation, and a resolutely anti-colonial stance.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

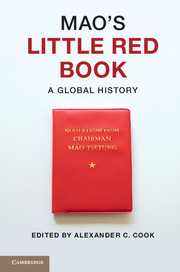

- Mao's Little Red BookA Global History, pp. 96 - 116Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2014

References

- 20

- Cited by