In 1924, the year when the United States shut its doors to all Japanese immigrants, Nagata Shigeshi embarked on a trip to Brazil to complete a land purchase. As the president of the Japanese Striving Society (Nippon Rikkō Kai), a leading Japanese migration agency of its day, Nagata planned to build Aliança, a new Japanese community, in the state of São Paulo to accommodate the supposed surplus population of rural Nagano. In addition to poverty relief, Nagata envisioned that the migration would turn the landless farmers of Nagano prefecture into successful owner-farmers in Brazil, who would not only serve as stable sources of remittance for their home villages but also lay a permanent foundation for the Japanese empire in South America. Rooted in social tensions in the archipelago, the anxiety of “overpopulation” in Japan was intensified by decades of anti-Japanese campaigns that raged in North America. White racism in the United States forced many Japanese migration promoters, including Nagata, to abandon their previous plans of occupying the “empty” American West with Japan’s “surplus” population. Instead they turned their gaze southward to Brazil as an alternative, seeing it as not only an equally rich and spacious land but also free of racial discrimination. A direct response to Japanese exclusion from the United States, the community of Aliança was designed to showcase the superiority of Japanese settler colonialism over that of the Westerners.Footnote 1 Meaning “alliance” in Portuguese, Aliança was chosen as its name to demonstrate that unlike the hypocritical white colonizers who discriminated against and excluded people of color, the Japanese, owners of a genuinely civilized empire, were willing to cooperate with others and share the benefits.Footnote 2 This idea quickly grew into the principle of kyōzon kyōei – coexistence and coprosperity – a guideline of Japanese Brazilian migration in general.Footnote 3

As the main direction of Japanese expansion shifted from South America to Northeast Asia in the 1930s, overpopulation anxiety was utilized by the imperial government to justify its policy of exporting a million households from the “overcrowded” archipelago to Manchuria, Japan’s new “lifeline.” Nagano prefecture continued to take on a leading role in overseas migration, sending out the greatest number of settlers among all Japanese prefectures to the Asian continent.Footnote 4 Nagata Shigeshi served as one of the core strategists assisting the imperial government’s migration policymaking, and he often referred back to Aliança as a model for Japanese community building in Manchuria.Footnote 5 Coexistence and coprosperity, the guiding principle of Japanese migration to Brazil, also became the ideological foundation of Japan’s Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere (Daitōa Kyōei Ken). After the empire’s demise, Nagata continued to identify overpopulation as the root of all social programs in the war-torn archipelago and kept on promoting overseas migration as the ultimate cure. Under his leadership, the Striving Society worked closely with the postwar government and managed to restart exporting “surplus people” from Japan to South America by reviving migration networks established before 1945.Footnote 6

The claimed necessity for Japan to export its surplus population has been dismissed by postwar historians as a flimsy excuse of the Japanese imperialists to justify their continental invasion in the 1930s and early 1940s. Likewise, according to conventional wisdom, the slogan of coexistence and coprosperity is nothing more than deceptive propaganda that attempts to cover up the brutality of Japanese militarism during World War II. Common examinations of Japanese expansion usually stop at 1945, when the Japanese empire met its end.

However, submerged in archives across the Pacific are stories of hundreds of Japanese men and women like Nagata Shigeshi, which the current nation-based, territory-bound, and time-limited narratives of the Japanese history fail to capture. They embraced the discourse of overpopulation and led and participated in Japanese migration-driven expansion that transcended the geographic and temporal boundaries of the Japanese empire. Their ideas and activities demonstrate that the association between the claim of overpopulation and Japan’s expansion had a long and trans-Pacific history that began long before the late 1930s. The idea of coexistence and coprosperity, embodied by Japanese community building in South America, was both a direct response to Japanese exclusion in North America and a new justification for Japanese settler colonialism based on the argument of overpopulation. It emerged in the 1920s, long before the announced formation of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere during the total war.Footnote 7 Furthermore, not only did Japan’s migration machine precede the war, it also survived it. The logic, networks, and institutions of migration established before 1945 continued to function in the 1950s and 1960s to spur Japanese migration to South America.

Why and how did the claim of overpopulation become a long-lasting justification for expansion? In what ways were the experiences of Japanese emigration within and outside of the empire intertwined? How should we understand the relationship between migration and settler colonialism in modern Japan and in the modern world? These are the questions that this book seeks to answer. This is a study of the relationship between the ideas of population, emigration, and expansion in the history of modern Japan. It examines how the discourse of overpopulation emerged in Japanese society and was appropriated to justify Japan’s migration-driven expansion on both sides of the Pacific Ocean from the mid-nineteenth century to the 1960s. Through the history of the overpopulation discourse, this study redefines settler colonialism in modern Japan by demonstrating the institutional continuities and intellectual links between Japanese colonial migration in Asia and Japanese migration in Hawaiʻi and North and South America during and after the time of the Japanese empire. It further reveals the profound overlaps and connections between migration and settler colonialism in the modern world, two historical phenomena that have been conventionally understood in isolation from one another.

Malthusian Expansionism and Malthusian Expansionists

I define the discourse of overpopulation that legitimized Japan’s migration-driven expansion on both sides of the Pacific as “Malthusian expansionism.” This is a set of ideas that demanded extra land abroad to accommodate the claimed surplus people in the domestic society on the one hand and emphasized the necessity of the overall population growth of the nation on the other hand. As two sides of the same coin, these seemingly contradictory ideas worked together in the logic of Malthusian expansionism. It rationalizes migration-driven expansion, which I call “Malthusian expansion,” as both a solution to domestic social tensions supposedly caused by overpopulation and a means to leave the much-needed room and resources in the homeland so that the total population of the nation could continue to increase. In other words, Malthusian expansionism is centered on the claim of overpopulation, not the actual fear of it, and by the desire for population growth, not the actual anxiety over it.

On the one hand, Malthusian expansionism echoed the logic of classic Malthusianism in believing that the production of a plot of earth was limited and could feed only a certain number of people. As early as 1869, three years before the newly formed Meiji government carried out the first nationwide population survey, it pointed to the condition of overpopulation (jinkō kajō) as the cause of regional poverty in the archipelago. As a remedy, the government concluded, surplus people in Japan proper should be relocated to the empire’s underpopulated peripheries.Footnote 8 From that point forward, different generations of Japanese policymakers and opinion leaders continued to claim overpopulation as the ultimate reason for whatever social tensions of the day were plaguing the archipelago. They also embraced emigration, first to Hokkaido and then to different parts of the Pacific Rim, as not only the best way to alleviate the pressure of overpopulation but also an effective strategy to expand the power and territory of the empire.

On the other hand, unlike Malthus’s original theory that held that population growth should be checked,Footnote 9 Malthusian expansionism celebrated the increase of population. The call for population growth emerged as Meiji Japan entered the world of modern nations in the nineteenth century, when the educated Japanese began to value manpower as an essential strength of the nation and a vital component of the capitalist economy. The size of population and the speed of a nation’s demographic growth, as Japanese leaders observed, served as key indicators of a nation’s position in the global hierarchy defined by modern imperialism. Accordingly, the emigration of the surplus people overseas would free up space and resources in the crowed archipelago to allow the Japanese population to continue its growth.

This study examines overpopulation as a political claim, not as a reflection of reality. Japan did experience periods of rapid population growth once it began the process of modernization, and it has historically been known as a densely populated nation/empire.Footnote 10 However, the word “overpopulation” should never be taken as given when discussing the contexts of emigration and expansion because the very definition of “overpopulation,” as this study has shown, has always been subject to manipulation. Like elsewhere in the world, the claim of overpopulation was associated with a variety of arguments and social campaigns in modern Japan. As Japanese economist and demographer Nagai Tōru observed at the end of the 1920s, the issue of overpopulation served as an excuse for different interest groups to advance their own agendas. Those who called for birth control were in fact working toward the liberation of proletarians and women; those who focused on the issue of food shortage might have cared more about political security than overpopulation per se; and in the same vein, migration promoters’ ultimate goal was the expansion of the Japanese empire itself.Footnote 11 By the concept of Malthusian expansionism, this book aims to explain how the claims of overpopulation were specifically invented and used to legitimize migration-driven expansion.

To this end, I focus on the ideas and activities of the Japanese migration promoters, men and women like Nagata Shigeshi, whom I call “Malthusian expansionists.” In other words, this is a study of the migration promoters, not the individual migrants who left the archipelago and settled across seas. Malthusian expansionists were different generations of Japanese thinkers and doers, who viewed migration as an essential means of expansion. Their diverse backgrounds shaped their agendas for emigration in different ways—those inside the policymaking circles envisioned that emigration would expand the empire’s territories and political sphere of influence, business elites saw emigration as a vital step to boost Japan’s international trade, intellectuals believed that migration would propel the Japanese to rise through the global racial hierarchy, social activists and bureaucrats used emigration to realize their plans to reform the domestic society, owners and employees of migration organizations and companies hoped for the growth of their wealth and networks, and journalists aimed to expand readership and influences.

However, as advocates of Malthusian expansionism, they claimed in unison that the archipelago, in part or as a whole, was overcrowded even though it was essential that the Japanese population continue its growth. They thus agreed with each other that emigration was both an ideal solution to the problem of overpopulation at home and a critical means of expansion abroad. In different historical contexts and in their own ways, they took on the primary responsibility to plan, promote, and organize Japan’s migration-driven expansion. Many not only extolled the merits of emigration through articles and speeches but also actively participated in migration campaigns by making policies and plans, investigating possibilities, or recruiting migrants.

To be sure, Malthusian expansionism was not the only design of empire in modern Japan. The ideas that the empire needed more population instead of less were constantly challenged by different forces from within and without. Kōtoku Shūsui, a pioneer of Japan’s socialist movement, made one of the earliest and most powerful critiques of Malthusian expansionism at the turn of the twentieth century. The argument that overpopulation necessitated emigration, he pointed out, was merely rhetoric for imperial expansion because the true reason behind the rise of poverty was not population growth but the increasingly imbalanced distribution of wealth.Footnote 12 From the late 1910s to the early 1930s, leaders of socialist and feminist movements in Japan were vocal in their push for contraception and birth control. Their birth control and eugenics campaigns were both inspired and empowered by contemporary international Neo-Malthusian and eugenic movements.Footnote 13 Similarly, not every Japanese empire builder favored emigration as a practical solution to Japan’s social problems and a productive means of expansion. As the tide of anti-Japanese sentiment began to rise in the United States, liberal thinkers like Ishibashi Tanzan argued that Japan should acquire wealth and power through trade instead of emigration. Ishibashi urged Tokyo to relocate all Japanese migrants in the United States back into the archipelago in order to avoid diplomatic conflicts.Footnote 14 As a whole, though Malthusian expansionists at times worked with other interest groups such as merchants, labor union leaders, and women’s rights advocates, they were also constantly vying for leadership and influence.

Not all types of emigration fit into the ideal scenario of expansion imagined by Japanese Malthusian expansionists either. Few of them saw the Korean Peninsula and Taiwan, two major colonies of the empire, which had two of the largest Japanese overseas communities by the end of World War II, as vital parts in their maps of expansion. Due to the high population densities of the native residents and the low living standards of the local farmers, the Japanese agricultural migration, favored by the Malthusian expansionists, had seldom succeeded there. Due to similar reasons, Okinawa, a colony turned prefecture of the empire, was rarely mentioned in the discussions of the Japanese Malthusian expansionists. The rich histories of Japanese migration in the Korean Peninsula, Taiwan, and Okinawa, therefore, do not feature prominently in this book.

Instead, I focus on the histories of Japanese migration in Hokkaido, California, Texas, Brazil, and Manchuria, where Japanese settlement was crucial for the evolution of Japanese Malthusian expansionism. Similarly, in the visions of Japanese Malthusian expansionists, not every ethnic group in the empire was qualified for emigration. Though having substantial differences among themselves, colonial subjects in the Korean Peninsula and Taiwan as well as outcast groups were generally excluded from the pool of ideal subjects of emigration.Footnote 15 Although Okinawa had one of the greatest numbers of emigrants among all Japanese prefectures, Malthusian expansionists did not consider Okinawans as ideal migrants either.Footnote 16

Malthusian Expansionism as a Logic of Settler Colonialism

By moving beyond geographical and sovereign boundaries, this study brings new ways to understand settler colonialism in the histories of modern Japan and the modern world. At a concrete level, it analyzes the links, flows, and intersections between Japanese migration within the imperial territory in Asia and that outside of the imperial territories in Hawaiʻi and North and South America and the continuities between Japanese overseas migration during and after the time of the empire. The connections between Japanese colonial migration in Asia and Japanese migration across the Pacific Ocean also present an intellectual necessity to conceptualize the overlaps between migration and colonial expansion. Thus, at a more theoretical level, by recognizing certain types of migration into the territories of other sovereign states as expansion, this study reconfigures the scope, logic, and significance of settler colonialism in world history.

Until recently, the experience of Japanese overseas migration has been divided into two contrasting narratives: a story of settler colonialism inside of the empire’s sphere of influence in Asia on the one hand and a story of Japanese migrants’ bitter struggles against white racism and immigration exclusion in other areas across the Pacific on the other. Recognizing the divergence between emigration (imin) and colonial migration/expansion (shokumin) remains absolutely necessary for us to grasp the different dimensions in the experience of the Japanese overseas. However, recent scholarship has moved our understanding of Japanese colonialism and expansionism beyond geographical and temporal boundaries of the Japanese empire.Footnote 17 As a result, the concepts of emigration and colonial expansion, together with the two separated narratives they represent respectively, are no longer sufficient because they cannot explain the continuities and connections between various waves of Japanese emigration on both sides of the Pacific Ocean from the beginning of the empire to the decades after its fall.

By not taking the conceptual division between migration and colonial expansion as given, this study illustrates the ideological and institutional continuities centered around the overpopulation discourse that persisted through different periods of Japanese emigration. The history of Japan’s Malthusian expansion transcended both the space and time of the Japanese colonial empire. I trace the origins of Japan’s Malthusian expansion to the beginning of Meiji era. I demonstrate how the migration of declassed samurai (shizoku) to Hokkaido during early Meiji, an episode commonly omitted from the history of Japanese colonial expansion, was a precursor to the ideas and practices of Japanese migration to North America and other parts of the Pacific Rim in later years. Likewise, Japanese migration to the United States that began in the last two decades of the nineteenth century also provided crucial languages and resources for Japanese expansion in South America and Northeast Asia from the early twentieth century to the end of World War II. I also extend the analysis into the postwar era and consider Japanese migration to South America in the 1950s and 1960s as the final episode in the history of Japan’s Malthusian expansion: though no longer performed by a militant and expanding empire, the postwar migration was still legitimized by the same discourse of overpopulation while driven by the same institutions and networks that were established during Japanese migration to South America and Manchuria before 1945.

That settler colonialism as a concept to describe the settler-centered colonial expansion and rule is different from military- or trade-centered colonialism has been widely accepted by scholars in recent decades. Yet researchers have utilized varied definitions of the term depending on the historical and political contexts of their subjects. The existing literature has offered at least three different definitions. First, in Anglophone colonial history, scholars use “settler colonialism” to describe the settling in colonies by colonizers and the establishment of states and societies of their own by usurping native land instead of exploiting native labor. The elimination of native peoples and their cultures and the perpetuation of settler states in the Anglophone history have led Patrick Wolfe to conclude that settler colonial invasion “is structure, not an event.”Footnote 18 Second, careful examinations of twentieth-century colonialism around the globe have extended our understanding of settler colonialism beyond the Anglophone model. Unlike the expansion of the Anglo world in the previous centuries, settler colonialism in the twentieth century was marked by the instability of settler communities. Whether in the Korean Peninsula, Abyssinia, or Kenya, colonial settlers from Japan, Italy, and Britain alike had to constantly negotiate their political and social space with more numerous indigenous populations. Their stories often ended with repatriation, not permanent stay. Accordingly, Caroline Elkins and Susan Pedersen have defined twentieth-century settler colonialism as a structure of colonial privileges based on the negotiation between four political groups: the settlers, the imperial metropole, the colonial administration, and the indigenous people.Footnote 19 Third, recent studies have started to extend the definition of settler colonialism beyond formal colonial sovereignty and power relations by exploring the overlaps and similarities between the experience of colonial settlers and that of migrants. Looking from indigenous perspectives, colonial histories of Hawaiʻi, Southeast Asia, and Taiwan, in their own ways, have all offered plenty of evidence of how immigrants ended up fostering the existing settler colonial structures.Footnote 20

Recognizing the overlaps between the experiences of settlers and migrants is the starting point of this research. I use the term “settler colonialism” by its most extended meaning, close to the third definition. However, different from all the approaches above, this book sheds new light on settler colonialism through the lens of migration itself. The migration of settlers is an essential component of settler colonial experience but has often been neglected. The migration-centered approach requires us to examine settler colonialism from both the sending end and the receiving end of settler migration. Existing literature of settler colonialism has provided rich insights from the receiving end. Scholars have explained in depth how a settler state is established and how the power structure of a settler colonial society is maintained.Footnote 21

This book examines the ideas and practices of settler colonialism at both ends of settler migration, highlighting the interactions between the social and political changes in the home country and those in the host societies. It seeks to explain how the emigration of setters was reasoned in the home country, why settlers demanded land more than anything else, and how settlers’ appropriation of the land owned by others was justified in both settler communities and the home country. I argue that Malthusian expansionism, which celebrates population growth and, in the meantime, demands extra land abroad to alleviate population pressure at home, lies at the center of the logic of settler colonialism in the modern era.

The migration-centered approach also allows me to examine the ideas and practices of settler colonialism beyond conventional boundaries. Though existing indigenous critiques have successfully problematized the very definitions of “settlers” and “migrants,” they are almost exclusively anchored in the host societies. I challenge the conceptual division between migration and settler colonialism from both ends of settler migration. Through the prism of Malthusian expansionism, this book shows that Japanese migration campaigns to the Americas and Hawaiʻi, territories of other sovereign states, were not only closely connected with the empire’s expansion in Asia but also propelled by settler colonial ambitions in Japan’s home archipelago.

Malthusian Expansionism in Four Threads

Why did Malthusian expansionism possess such appeal and adaptability in modern Japanese history? How did it make sense to Japan’s nation and empire builders from distinct socioeconomic backgrounds? How was this demographic discourse embraced in drastically different historical contexts to justify Japan’s migration driven expansion? To explain the power, mechanism, and significance of Malthusian expansionism, one must look beyond the realm of thoughts and words of the elites. My analysis focuses on how ideas interacted with social realities, political actions, and historical changes. It pinpoints four different but overlapping threads within the big picture of Japanese Malthusian expansion: the intellectual, the social, the institutional, and the international.

First and foremost, the history of Malthusian expansionism is a unison of two schools of thoughts – overpopulation and expansion. I explain how the claim of overpopulation that justified emigration originated and how it continued as a dominant discourse in modern Japan’s shifting intellectual debates of empire building, both among academics and in the public sphere. Second, this is also a study of social and cultural history that discusses how Malthusian expansionism took root in and was also transformed by the changing social and political contexts within the archipelago. It explores how a succession of social movements, each in response to specific sociopolitical tensions, turned to overpopulation for an easy diagnosis and portrayed emigration as the panacea. Beyond social movements, Malthusian expansionism also found expression in the form of specific laws and state apparatuses. Thus, the third thread reveals how it both influenced and was strengthened by government institutions, policies, and legislations, at both central and local levels, that aimed at managing reproduction and emigration. Finally, as a major player in the arena of modern imperialism, Japan’s expansion was inevitably shaped by its uneasy relationship with other empires. The fourth thread examines how the Japanese empire’s imitation of – as well as struggles against – Anglo-American expansion both molded and transformed the ideas and activities of Japanese Malthusian expansionists.Footnote 22

The Intellectual: Population, Land, the Lockean Principle of Ownership

From the beginning of the Meiji era, educated Japanese both within and outside of the government started collecting massive amounts of information about their nation, including its population, land, and produce.Footnote 23 Follow the example of their Western counterparts, Meiji leaders believed that the country could not be known and managed effectively without the collection of data. From 1872 onward, as a part of this “statistics fever” (tōkei netsu),Footnote 24 the Meiji government began conducting nationwide population surveys based on information provided by the newly reconstituted household registration system.Footnote 25

Along with this faith in numbers, Meiji intellectuals also found new ways of understanding the meaning of ordinary life. The masses were no longer a sea of ignorant people (gumin) who were destined for political exclusion. Instead, educated Japanese began to see every individual in the archipelago as a valuable subject of the new nation, whose well-being was a critical indicator of the nation’s strength and prosperity.Footnote 26 Beginning in early Meiji, as a result of the introduction of modern medicine and hygiene, the archipelago entered a phase of rapid population growth. Japanese intellectuals spared no efforts to celebrate the population boom as evidence for both the success of the new government and the superiority of the racial stock. In this spirit, they ranked the Japanese as one of the most demographically expanding races in the world, right alongside the Europeans.Footnote 27

It was in this intellectual context that educated Japanese introduced Thomas Malthus to their domestic readers. From the late nineteenth century onward, while the call for birth control was constantly contested,Footnote 28 the Malthusian argument that land had a finite limit on the population it could sustain was widely accepted as common sense in the society. Thus overpopulation, a natural result of the rapidly growing population within the limited territory of the empire, became a critical issue that Japanese thinkers of different generations would all contend with.

The discovery of the existence of a “surplus population” in Japan came at a time when Meiji intellectuals began to reexamine the world’s political geography by referring to past – and ongoing – Western colonial expansions. In particular, the history of Anglo-American settler colonialism became their primary source of inspiration. Unlike the Iberian expansionists, whose central goals for colonization were securing tribute, labor, taxes, and the ostensible loyalty of indigenous inhabitants, the Anglo-American colonialists focused on the acquisition of land itself.Footnote 29 Armed with a new language drawn from the Enlightenment, they also sought to justify their taking of aboriginal lands in the name of reason and progress.Footnote 30

This conceptual shift was spearheaded by the British Enlightenment thinker John Locke. Through his involvement in drafting and revising The Fundamental Constitutions of Carolina in the late seventeenth century, Locke had participated in the British Empire’s expansion in North America.Footnote 31 In his widely acclaimed Two Treatises of Government, Locke defined agrarian labor, which included both the act of enclosure and the act of cultivation, as the only legitimate foundation of claiming land ownership. Any land without the presence of agrarian labor, no matter if occupied or not, was wasted and thus open to appropriation.Footnote 32 The Lockean principle of land ownership was cited by colonial thinkers on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean to justify British settlers’ rejection of the indigenous land rights and legitimize the establishment of settler colonies in North America.Footnote 33 While the postindependence US government initially recognized some Native American tribes’ land ownership, by the late nineteenth century it had dispossessed Native Americans of most of their lands through negotiation, purchase, political maneuver, and military action. The Lockean principle, meanwhile, continued to serve as a central justification for this process.Footnote 34 In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, it not only propelled British colonial expansion and land acquisition in other parts of the world but also inspired other modern empires in their own expansion projects.Footnote 35

Informed by the experience of Anglo-American settler colonialism and this new concept of land ownership, Japanese expansionists considered it the natural right of the Japanese, members of a civilized and industrious race, to participate in the imperial scramble for vacuum domicilium in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. As Japan’s colonial empire continued to grow, different generations of Malthusian expansionists saw a succession of locales – Hokkaido, Karafuto, the Bonin Islands, Okinawa, the Korean Peninsula, Taiwan, and eventually Manchuria – as empty and unworked, eagerly waiting for Japanese settlers to claim. The inconvenient fact that many of these places were already densely populated had no bearing on their narratives. Furthermore, in different historical contexts but according to the same Lockean principle, Japanese expansionists also saw potential targets of Malthusian expansion in the de facto territories of Western colonial powers and independent nations, such as the United States, Brazil, Peru, Hawaiʻi, Australia, New Zealand, and the Philippines. In their imaginations, although already under the control of nation-states or colonial empires, these territories remained partially empty and unworked due to the low density of white population. As an equally civilized people from an overpopulated archipelago, the Japanese had the right to claim a share of ownership by competing against or cooperating with white settlers in these lands.Footnote 36

While Japanese Malthusian expansionists drew their world maps of expansion according to the Lockean principle, modern capitalism enabled them to view the emigration of surplus people as a process of economic growth and material accumulation. For them, the purpose of emigration was to enlarge the empire’s population and increase its wealth. Since the very beginning of the empire, population increase was celebrated alongside economic development. The inseparability between demographic and economic growth in Meiji colonial thoughts was self-evident in the literal meaning of some Japanese terms used to describe colonialism and expansion. The word shokumin 殖民, a translation of “colonial migration,” was an early Meiji invention that combined the character shoku 殖 (meaning “to increase”) and the character min 民 (meaning “people”).Footnote 37 This translation was a clear indicator of how colonial migration was understood in the early Meiji period – it was, at least partially, an action designed for population enlargement. The fact that the programs of shokusan 殖産 (to develop the economy) and shokumin 殖民 often appeared in tandem revealed the ideological connections between the increase of economic output and that of manpower throughout the history of the Japanese empire.Footnote 38 Another word, takushoku 拓殖, was also invented around the beginning of the Meiji period to combine takuchi 拓地 (to explore land) with shokumin 殖民.Footnote 39 It indicated that the acquisition of material wealth and the increase of population were consistently regarded as two sides of the same coin.

Such a connection was only natural because for Japan, as it was for other modern empires, the act of projecting power beyond its original territory went hand in hand with its embrace of modern capitalism. Ever since the beginning of the modern era, the territorial expansion of nation-states had been intertwined with their search for materials and markets. As Japan’s migration-driven expansion evolved in response to the changes of domestic and global environments, places such as Hokkaido, California, Mexico, Hawaiʻi, the South Pacific Islands, Texas, Brazil, the Korean Peninsula, and Manchuria, one after another, came to be described as the empire’s “sources of wealth” (fugen). These destinations were invariably portrayed as spacious, empty lands with abundant natural resources, ideal for not only accommodating the surplus Japanese people but also supplying materials to feed the hungry archipelago.Footnote 40 In the 1930s, as the empire’s total war put unprecedented demands on resources, the trope of fugen took on a life-or-death significance and evolved into that of “lifeline” (seimeisen) during Japan’s mass migration to Manchuria.Footnote 41 As Japan’s overseas migration restarted at the beginning of the 1950s, South American countries that received most of the Japanese postwar emigrants were no longer portrayed as empty; nevertheless, they continued to be described as primitive but abundant in natural wealth, waiting for the civilized Japanese to explore and utilize.Footnote 42

The Social: Class, Conflicts, and Overpopulation

The discourse of Malthusian expansionism in Japan was deeply rooted in the political contexts of the society and was constantly influenced and galvanized by a succession of social movements in the archipelago. For Malthusian expansionists, the core purpose of emigration was a two-pronged one: to export surplus people abroad in order to alleviate domestic tensions and, at the same time, to pursue wealth and power for the empire by turning these displaced people into useful subjects abroad. The coexistence of these two identities of the emigrants – troublemakers in the overcrowded archipelago and trailblazers of the empire overseas – closely tied Malthusian expansionism to different social movements in modern Japan.Footnote 43 Some of these social movements were initiated by the state, others were spearheaded by nongovernmental groups, but they all responded to specific social tensions and economic pressures of their times. As the following chapters explain in detail, the early Meiji movement to resettle shizoku was motivated by the perceived political threat posed by the newly declassed samurai. The socialist movement at the turn of the twentieth century was triggered by the rise of the working class and their call for political and economic rights. The agrarian movement that peaked in the 1930s was ushered in by prolonged economic depression and intensified land disputes in the countryside. The post–World War II land reform and land exploration programs were, in a way, responding to the urgent need for accommodating the millions of Japanese who lost their livelihood due to the war and the subsequent decolonization. Be they unwilling or unable to challenge the powerful status quo, leaders of different social movements often pointed to overpopulation as a root cause of the social crises of their times. Similarly, because it circumvented political confrontation, emigration constantly served as one of the most pragmatic prescriptions for Japan’s social ills.

As Japan’s nation-making and empire-building processes proceeded hand in hand, its Malthusian expansionists also incorporated the calls for domestic changes into their blueprints for the empire’s expansion. Coming from different social backgrounds and active during different periods, they held divergent and at times contradictory views on what the Japanese nation-empire was and should be. Yet they uniformly imagined that large-scale emigration would not only free Japan from population pressure but also transform idle individuals into vanguards of the empire. For this reason, the questions of who exactly these surplus people were and how they should be called into service for the empire were as political as the definition of overpopulation itself.

In response to different social and political tensions, Malthusian expansionists had designated men and women of specific social strata as the ideal candidates for migration. The definition of strata also grew more diverse, moving from an inheritance-based caste to social and economic classes. This evolution itself testifies to the gradual horizontalization of the Japanese society, with the vertical feudal hierarchy yielding to the supposedly egalitarian social structure of the modern era. Those who were identified as “surplus” people shifted from the declassed samurai who posed immediate political dangers to the newly established Meiji regime to the commoner youth in late Meiji who had scant opportunities to realize their ambitions, from poor farmers suffering from continuous rural depression in the early twentieth century to almost everyone who failed to find a place in the war-torn archipelago after 1945.

For each of the successively targeted social groups, the Malthusian expansionists had designed specific missions for their migration according to their historical contexts. The declassed samurai in early Meiji were instructed to dedicate their talent and energy to defend the empire’s northern territory and to civilize the barbarian land by tapping its natural wealth.Footnote 44 Ambitious youth from common families at the turn of the twentieth century were to establish themselves in the United States by acquiring education, managing businesses, or running farms; they were expected to secure a strong foothold for the Japanese race in the white men’s world by the merit of their personal success.Footnote 45 Between the 1920s and 1945, the rural poor were urged to become owner-farmers in Brazil and Asia and put down permanent roots for the Japanese empire.Footnote 46 Finally, the postwar homeless and jobless were called upon to tame the wild lands in South America and represent the new Japan as a surrogate of the West during the Cold War, bringing the blessings of democracy and modernization to the underdeveloped countries.Footnote 47 Emigration, in sum, was expected to transform Japan’s surplus people into productive subjects of the empire and nation.

The Institutional: The Control of Reproduction and the Making of the “Migration State”

Beyond the existence of an intellectual foundation and deep-reaching sociopolitical roots, Malthusian expansionism was also codified into laws and implemented by a number of governmental or quasi-governmental institutions. The history of Japanese Malthusian expansionism was thus also a history of state expansion in both biopolitics of controlling population reproduction and geopolitics of managing expansionist migration. This process of state expansion culminated in the formation of what I call the “migration state” in the late 1920s. By the end of World War II, the migration state had sponsored and managed the migration of hundreds of thousands Japanese subjects to South America, Manchuria, and Southeast Asia. Except for a temporary interruption immediately after World War II, this migration state continued to function into the 1960s. The expression of Malthusian expansionism in the form of state policies and regulations was part and parcel of the modern Japanese state’s social management, a process that involved constant negotiations with intellectuals and social groups.Footnote 48

Like its Western counterparts, the modern Japanese state took shape hand in hand with its discovery of population as a political force that had to be not only monitored and controlled but also cultivated and guided.Footnote 49 Considering population to be an essential indicator of national strength, the Meiji state swiftly inserted itself into the sphere of reproduction. In 1868, the same year of its own formation, the government banned midwife-assisted abortion and infanticide. In 1874, the Ministry of Education (Monbushō) began to regulate the midwifery profession by requiring prospective midwives to receive professional training and gain state-issued licenses. In 1899, the government further promulgated a set of laws that recognized midwifery as a modern profession and put it under state monitoring. Modeled after its counterparts in modern Europe, the new and professionalized midwifery was quickly enshrined as a crucial occupation that safeguarded the life of infants, thereby laying the foundation for “enriching the nation and strengthening the army” (fukoku kyōhei).Footnote 50 In 1880, the government criminalized the act of abortion itself, and in 1907 it further clarified the definition of the crime and increased its punishment.Footnote 51 However, despite increasingly strict regulations on paper, their spotty enforcement was evidence that the government’s stance toward reproductive crimes was not always consistent.Footnote 52

In addition to ensuring population growth, Japan’s policymakers also consciously drew a causal relationship between the existence of overpopulation and social issues (shakai mondai) such as poverty, economic inequality, and crimes. For the government, overseas emigration gradually became a primary solution to a host of domestic problems. Even before the first nationwide population survey was conducted, Meiji leaders had already concluded that the unequal distribution of population within Japan proper and Hokkaido was a cause of regional poverty and used this claim to rationalize their policies of sending the declassed samurai to the empire’s northern frontier.Footnote 53

Yet before the 1920s, the institutional links between emigration and domestic affairs remained inconsistent. The matter of overseas migration was classified under the umbrella of diplomacy and largely managed by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Even as the ministry strove to explore new destinations overseas for Japanese emigration, it also imposed increasingly stringent restrictions on emigration in order to maintain Japan’s international image as a civilized empire. In 1894 it issued the Emigration Protection Ordinance, which went into effect two years later. Revised a few times through 1909, the ordinance gave the government the right to restrict and even suspend overseas travel for Japanese subjects.Footnote 54 The Japanese government’s restriction on emigration reached its peak with the Gentlemen’s Agreement of 1907, according to which it banned all Japanese subjects from migrating to the continental United States as laborers.

From the 1920s through the end of World War II, the imperial government redoubled its efforts to control reproduction and facilitate emigration. In 1920, the government started to conduct national censuses regularly.Footnote 55 Also beginning in the early 1920s, the majority of the births in the archipelago were assisted by professionally trained and state-certified midwives who had no tolerance for infanticide or abortion. The reproductive laws were also enforced more vigorously.Footnote 56 Although advocates for birth control and eugenics gained increasing popularity after World War I, the imperial government never legalized contraception. The state also managed to further expand its control over reproduction by collaborating with some prominent eugenicists under the common goal of strengthening the empire’s racial stock. In 1941, during the total war, the government promulgated the National Eugenic Protection Law, aiming to both permanently maintain a high birth rate and improve the physical quality of the Japanese population.Footnote 57

In the early twentieth century, the Ministry of Home Affairs emerged as a key government branch in migration management. Two years after the Rice Riots of 1918, the ministry established the Bureau of Social Affairs in charge of unemployment issues and emigration promotion.Footnote 58 The formation of the bureau marked the beginning of the state’s institutional integration of overseas emigration with domestic social issues. From then on, the imperial government – at both central and local levels – became involved in the processes of migration promotion and management on an unprecedented scale, eventually giving birth to what I define as the Japanese “migration state.” The Ministry of Home Affairs began to subsidize emigrants to Brazil in 1923, and later also provided financial aids to emigrants heading to other destinations. In 1927, the Tanaka Gi’ichi Cabinet established the Commission for the Investigation of the Issues of Population and Food (Jinkō Shokuryō Mondai Chōsakai) and staffed it with prominent demographers, economists, and emigration advocates. As a cabinet think tank that continued to function into the 1930s, the commission was put in charge of designing government policies on both reproduction and emigration. Members of the commission saw overpopulation as a root cause of Japan’s social ills, but they were also convinced of the absolute necessity of maintaining Japan’s population growth.Footnote 59 For them, overseas migration was an ideal solution to many problems faced by the Japanese empire.

The promulgation of the Overseas Migration Cooperative Societies Law (Kaigai Ijū Kumiai Hō) in 1928 authorized each prefecture to launch its own overseas emigration projects and build communities abroad.Footnote 60 As a result, a few prefectural governments played important roles in the mobilization of Japanese migration to Brazil and later Manchuria between the late 1920s and 1945.Footnote 61 Beginning in the early 1930s, the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry (Nōrinshō) also participated in emigration promotion and management.Footnote 62 Embracing the logic of Malthusian expansionism, its policymakers claimed that the vast land in Manchuria was the ultimate rescue for landless farmers in the overcrowded archipelago.Footnote 63

The empire’s collapse and the subsequent US occupation brought emigration-related apparatuses of the imperial government to a halt. However, significant institutional continuities between the imperial and postwar governments allowed Malthusian expansionism to reemerge in postwar Japan. The new government embraced the discourse of overpopulation to explain its inability to solve a number of urgent social problems right after the war. After the US occupation ended, the migration state quickly came back to life; with the institutional structures and networks built back in the 1920s and 1930s, it now redirected Japanese migrants to South America. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, engines of the migration state before 1945, continued to drive the migration machine in the postwar era until the decline of Japanese emigration and Malthusian expansionism itself in the 1960s.Footnote 64

The International: Anglo-American Expansion, White Racism, and Modern Settler Colonialism

In addition to the intellectual, social, and institutional contexts, the advent and evolution of Malthusian expansionism in Japan was also a byproduct of Anglo-American expansion around the world. At first glance, the parallels between imperial Japan’s call for additional land to accommodate its surplus population, the Third Reich’s thirst for Lebensraum, and the demand for Spazio vitale by Mussolini’s Italy appear self-evident. As this book demonstrates, however, it was the British settler colonialism in North America and the US westward expansion that truly inspired and informed the Japanese Malthusian expansionists. Japan’s uneasy interactions with the Anglo-American global hegemony had a significant impact on the trajectory of Japanese Malthusian expansionism.

From the beginning of the Meiji era, Japan’s leaders were impressed by the history of Anglo-American expansion and followed it as a textbook example for Japan’s own project of empire building. To rationalize this imitation, they spared no effort to claim similarities between the Japanese and the Anglo-Saxons. The influential Meiji economist and journalist Taguchi Ukichi, for example, argued that Japan’s population growth proved that the Japanese were as superior as the Anglo-Saxons.Footnote 65 The colonization of Hokkaido, the first target of the Meiji empire, was carefully modeled after Anglo-American settler colonialism in general and the US westward expansion in particular.Footnote 66 As the Japanese expansionists’ gaze shifted overseas, the American West became one of the first ideal destinations for Japanese emigration: by going to the western frontier of American expansion, not only would the Japanese be able to learn firsthand from Anglo-American settlers, they would also participate in the colonial competition against them.Footnote 67

To be sure, though bearing close connections and parallels, the histories of the British and the US empires followed divergent paths. Even in the region of North America, British settler colonialism and the US westward expansion stood apart from each other in both temporal and political contexts. What the Japanese empire builders described as the expansion of the “Anglo-Saxons” was usually based on their oversimplification and misunderstanding of these two highly complicated experiences.Footnote 68 Nevertheless, these misinterpretations did not prevent them from borrowing the core ideas of Malthusian expansionism from their British and American counterparts.Footnote 69

The decades of the 1910s and 1920s marked a watershed in the history of Japanese Malthusian expansionism. Up until this point, the legitimacy of Japanese emigration rested upon the self-claimed similarities of the Japanese to the Anglo-Saxons, but now Japanese thinkers began to challenge Western settler colonialism and Anglo-American hegemony in order to promote Japan’s own version of settler colonialism. This change was a response to the waves of anti-Japanese sentiment in the Anglo world that culminated in two international events: the Allies’ rejection of Japan’s proposal to write the clause of racial equality into the Treaty of Versailles in 1919 and the passage of the Immigration Act of 1924 in the United States.Footnote 70 Japanese Malthusian expansionists believed that as their empire was suffering from the crisis of overpopulation, Japan naturally deserved the right to export its surplus people overseas. However, this impeccably reasoned request, in their imaginations, was frequently denied, for the racist white men had reserved their vast and largely empty colonial territories around the Pacific Rim for their own people.Footnote 71

As tensions between Japan and the United States continued to mount in the Asia-Pacific region, an increasing number of Japanese expansionists began to underscore and glorify the uniqueness of Japanese settler colonialism. Though Japan’s Malthusian expansion continued to draw inspirations from the Anglo-American model in reality, it was increasingly portrayed as being guided by the unique principle of “coexisting and coprospering” with the native peoples. This principle, they argued, demonstrated the benevolent nature of Japanese expansion, which set them apart from the hypocritical white imperialists.

From the late 1930s to 1945, when Japan embarked upon a total war with the United States and the United Kingdom in the Asia-Pacific region, the idea of coexistence and coprosperity was enshrined as the ideology of its new world order known as the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere. In their assuredly righteous struggle against white racism and the Anglo world, Japanese Malthusian expansionists considered a strong and growing population to be their best weapon: not only did it point to an increase of the overall strength of the empire, it also offered evidence of Japanese superiority over white men. In the minds of Japanese expansionists, racism was the indelible mark of Anglo-American hypocrisy that would lead white men to their downfall. A wartime survey published by the Japanese Ministry of Welfare gleefully noted that the population of Australia had already begun to decline due to a long history of excluding of Asian immigrants from the country.Footnote 72 In contrast, the overall population in the Co-Prosperity Sphere continued to grow at an impressive speed. More importantly, the Japanese, as the leading race (shidō minzoku), were willing to cooperate with the lesser races. Therefore, they were fully capable of using this formidable resource to empower their empire; by doing so, they would succeed in their mission to build a new and liberated Asia.Footnote 73

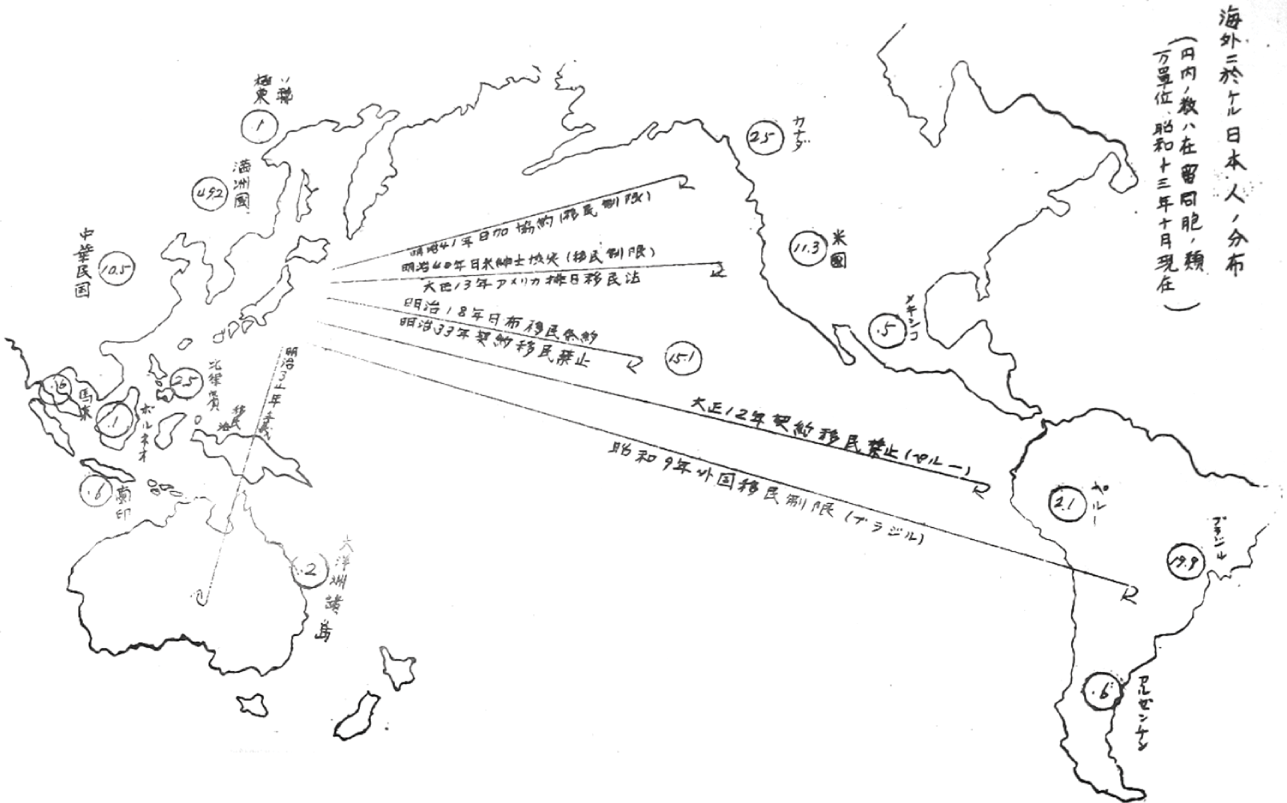

Figure I.1 This map, made in 1937 based on data from the Japan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, illustrates the sizes of Japanese overseas communities around the Pacific Rim. It also presents a causal link between the exclusion of the Japanese migration in Australia and North and South America and the Japanese migration-driven expansion in East Asia. Kōseishō, Jinkō Minzokubu, Yamato Minzoku o Chūkaku to Suru Sekai Seisaku no Kentō, no. 6, in Minzoku Jinkō Seisaku Kenkyū Shiryō: Senjika ni Okeru Kōseishō Kenkyūbu Jinkō Minzokubu Shiryō, vol. 8 (repr., Tokyo: Bunsei Shoin, 1982), 2811.

These imperial designs, however, would have to remain unrealized. Japan’s defeat in World War II and the subsequent US occupation led to yet another turning point in the evolution of Japan’s Malthusian expansionism. Postwar Japan’s policymakers and migration promoters quickly embraced the American hegemony in the Western world by characterizing Japanese emigration as not only a solution to social crises in the war-torn archipelago but also a mission of exporting modernization. Emigration now became a way for the new Japan to solidify its position in the Western Bloc by enlightening Third World countries during the Cold War.

A Global History of Malthusian Expansionism

Examining the history of modern Japan from the perspective of Malthusian expansionism allows us to rethink the relationship between life and land, between migration and expansion in the global history of settler colonialism. As students of modern imperialism, Japanese leaders were quick to adapt to social Darwinism, and they saw the Western empires’ territorial and demographic expansion as the guidebook for Japan’s own project of empire making. Though this might strike today’s readers as utterly counterintuitive, educated Japanese in different periods of the empire had imagined the snowy Hokkaido as Japan’s very own California and hailed the northern Korean Peninsula as “Brazil in the frigid zone” (Kantai Burajiru).Footnote 74

Similarly, Malthusian expansionism was not a Japanese invention. As a global discourse that served to justify modern settler colonialism, it had a long history that predated the rise of the Japanese empire. Its intellectual roots can be traced back to the formative years of modern nation-states in Europe, when Enlightenment thinkers began to discover the news meanings of population. Philosophers and political theorists such as Voltaire, Montesquieu, David Hume, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, and Thomas Paine all saw a large and growing population as evidence of social prosperity. The ability to sustain a rapid rate of population growth became a standard criterion by which a modern government’s performance was judged.Footnote 75 The celebration of population increases also grew together with the emergence of demography as a modern discipline in Europe, allowing the nascent modern states to collect and use demographic data in order to control and manage their subjects.Footnote 76

Due to the fear that people’s fertility rate would drop once they settled overseas, population surveys were conducted in settler colonies earlier and more often than back in the metropoles.Footnote 77 The superior population growth rate in the North American colonies, however, convinced the British expansionists that settler colonialism was an ideal strategy to boost population size of the entire empire. In 1755, Benjamin Franklin, then still a loyalist to the British Crown, published a book in Boston to drum up support for the ongoing Seven Years’ War. From a demographic perspective, he took pains to convince his readers that the war was worth fighting in order to secure and expand British colonies in North America. A swelling population, he argued, was crucial for the fate of every nation. However, if a land was fully occupied, those who did not have land would become mired in poverty because they would have to labor for others under low wages. Then due to poverty, landless people would have to stave off marriage in order to keep their living standards. This, in turn, would stop population growth.Footnote 78

Contrasting to the overcrowded Europe, Franklin argued, the vast and empty North America was occupied by only a negligible number of Indian hunters. It had an abundance of cheap land that both European settlers and their offspring could easily obtain. For this reason, the average age of marriage among the British settlers in North America was younger than that in Britain. Franklin thus believed that the population in the British colonies in North America had been growing at full speed, with its size doubling every twenty-five years. Within a century, he predicted, the number of British settlers in America would exceed the population in the British Isles.Footnote 79

With this vision, Franklin rejoiced in the population growth of the British settlers in North America and what it portended for the British Empire: “What an accession of Power to the British Empire by the Sea as well as Land! What increase of trade and navigation! What numbers of ships and seaman! We have been here but little more than one hundred years, and yet the force of our Privateers in the late war, united, was greater, both in men and guns, than that of the whole British Navy in Queen Elizabeth’s time.”Footnote 80 To emphasize the importance of North American colonialization, Franklin further explained how settler colonialism would foster both demographic and territorial expansion for the British Empire. A nation, he reasoned, was like a polyp: “Take away a limb, its place is soon supplied; cut it in two, and each deficient part shall speedily grow out of the part remaining.” Referring to the land of North America, he continued, “if you have room and subsistence enough, as you may by dividing make ten polyps out of one, you may of one make ten nations, equally populous and powerful.”Footnote 81 In his vision, the British colonies in North America offered the essential space for the British Empire to continue growing in both population and strength.

Franklin’s theory about the rapid population increase in British North America was soon picked up by many publications in the British Isles as joyful common sense. In particular, Franklin’s assumption that the size of British settlers’ population in America would double every twenty or twenty-five years became a central inspiration for Thomas Malthus to compose his fundamental thesis on population.Footnote 82 In 1789, in An Essay on the Principle of Population, Malthus laid out his demographic theory that human population, if left unchecked, would grow in a geometrical ratio while subsistence for mankind could increase only in an arithmetical ratio.Footnote 83 To prove this theory, Malthus took the newly independent United States and Britain as two contrasting empirical cases. He picked up Franklin’s hypothesis and defined American settler communities as an illustration for how fast human population could grow when given an abundance of land and subsistence. Britain, on the other hand, was a lesson on how overpopulation would take its toll by pushing millions into poverty.Footnote 84

The publication of An Essay on the Principle of Population was indeed a milestone event in the global history of demographic thoughts. By proposing that food production could never keep up with population growth within a given amount of land, Malthus forcefully established a causal link between population growth, poverty, and social disorder and gave a scientific voice to the anxieties about overpopulation that had already been emerging in Britain and France at the time.Footnote 85 The flame of fear was further fanned by the explosion of urban population and revolutions throughout Europe during the first half of the nineteenth century.Footnote 86 During the following decades, as Malthusianism gained increasing prominence, it also became a point of contention among different social forces. Nevertheless, it would be difficult to overestimate Malthusianism’s impact on social movements and state policies throughout the world to this day.

However, the rise of Malthusianism by no means brought an end to the celebration of population growth in the imperial West. Throughout the nineteenth century, expansionists in the British Isles continued to hail population growth as an indicator of power and progress both in the metropole and in the colonies. In 1853, the Manchester Guardian happily claimed that the enormous increase of the Anglo-Saxons since the beginning of the century marked Great Britain’s grand transition from a kingdom into an empire.Footnote 87

In this context, visionaries of imperialism embraced the idea of the “Malthusian nightmare” as a central justification for settler colonial expansion. While educated Britons had advanced the idea that the coexistence of an overpopulated and industrious nation and the vacant foreign land necessitated the expansion of the former to the latter as early as the sixteenth century,Footnote 88 it was Malthus who, for the first time, vested this idea with scientific reasoning. None other than Malthus himself had praised the British colonies in North America as a successful example of how population growth could reach its full scale given sufficient land.Footnote 89 The ideas of Malthus became the intellectual foundation of Robert Wilmot-Horton’s proposals to relocate the British poor to Upper Canada. Wilmot-Horton managed to implement some of his emigration plans and chaired the Select Committee on Emigration in the British government in the 1820s.Footnote 90 The Malthusian theory also inspired Wilmot-Horton’s acquaintance, Robert Gouger, to establish the National Colonization Society in England in 1830: by promoting colonial migration to Australia, he would free the United Kingdom of its paupers. Gouger is known as one of the founders of South Australia and also served as its first colonial secretary.Footnote 91 In 1895 Cecil Rhodes promoted British settler colonialism in Africa in the same logic by declaring, “My dearest wish is to see the social problem solved: that is to say that in order to save the forty million inhabitants of the United Kingdom from bloody civil war, we colonial politicians must conquer new lands to take our excess population and to provide new outlets for the goods produced in our factories and mines. The empire, as I have always said, is a question of bread and butter. If you do not want civil war, you must become imperialists.”Footnote 92

Malthusian expansionism also undergirded the westward expansion of the United States. In 1803, Thomas Jefferson argued that the rapid increase of the white American population made it necessary for the Native Americans to abandon hunting in favor of agriculture in order to free up more land for white settlers.Footnote 93 To this end, he began to envision a relocation of the Native American tribes to the western side of the Mississippi in order to leave the entire eastern side of the river to white farmers.Footnote 94 Jefferson’s idea was eventually materialized in the passage of the Indian Removal Act by the American Congress in 1830, which authorized US president Andrew Jackson to relocate Native Americans residing in the Southeast to the other side of the Mississippi. The promulgation of the Homestead Act of 1862, on the other hand, hastened US westward migration and agricultural expansion by granting eligible settlers public land in the American West after five years of farming.Footnote 95 In 1903, looking back to the history of US expansion in the nineteenth century, Frederick Jackson Turner celebrated the “free land” in the western frontier as the safety valve of American democracy and individualism. Whenever the civilized society in the East was troubled by population pressure and material restraints, he concluded, settlers could always pursue freedom by taking the empty land in the West.Footnote 96

While the “closing of the frontier,” observed by Turner at the turn of the twentieth century, led to a rising overpopulation anxiety among conservative American intellectuals, their liberal counterparts continued to celebrate population growth as the fountain of the nation’s wealth and power.Footnote 97 Similarly, the falling birth rates in the United Kingdom and France and the rise of imperial Germany in the late nineteenth century further marginalized the cause of birth control advocacy in British and French societies. The educated Europeans were also worried that the declining birth rate of the upper classes and the rising birth rate of the lower classes would lead to an overall degeneration of their racial stocks. The eugenic movement gained momentum in Europe and North America at the turn of the twentieth century by encouraging the reproduction of the “fit” and forbidding that of the “unfit.”Footnote 98 Major international wars from the end of the nineteenth century to the mid-twentieth century, including the Second Boer War, the Russo-Japanese War, World War I, and World War II, turned both the quantity and quality of population into an issue of life and death for policymakers of all major powers.

The Japanese empire entered the global scene of imperial rivalry at a time when the majority of land territories around the world had already been seized either formally or informally by other colonial powers. The Japanese expansionists could no longer replicate the sweeping conquest of terra nullius like their Anglo-Saxon counterparts. Along with warfare, emigration to sovereign territories (either colonies of other empires or settler nations) became one of the few options the empire had to pursue wealth and power. The Japanese empire builders embraced Malthusian expansionism at this particular moment. They celebrated the demographic explosion in the archipelago as evidence of the racial superiority of the Japanese and demanded an outlet for the empire’s surplus population. At the turn of the twentieth century, they believed that California, a sparsely populated frontier of American westward expansion, not only was a guide for Japan’s own expansion in Hokkaido but also should be a frontier of the Japanese subjects themselves.Footnote 99 The “empty” and “wealthy” land of Brazil was likewise seen in the 1920s as an ideal destination for millions of Japanese landless farmers rather than a mere metaphor to encourage Japanese migration to Northeast Asia.Footnote 100

The immigration of Asians to European colonies and settler nations soon triggered the first concerted efforts to regulate global migration. At the turn of the twentieth century, the United States, Australia, Canada, as well as European colonies in the Asia-Pacific region began to impose race-based immigration restrictions that aimed to exclude Asian immigrants. However, as Tokyo had justified Japanese emigration using the logic of Anglo-American expansion, the Anglophone scholars and politicians were forced to take the Japanese empire’s demands seriously. In the 1920s and 1930s, overpopulation in Japan was widely recognized as scientific truth in the West.Footnote 101 Warren Thompson, a leading American sociologist and one of the most widely cited scholars in demographic studies in the West, argued in 1927 that due to the population pressure in Japan, “we should recognize that the urge towards expansion is just as legitimate in the Japanese as in the Anglo-Saxons.”Footnote 102 Thompson believed that in the interest of avoiding military conflicts, the Anglophone countries should cede some unused lands in the Pacific region to meet the needs of an expanding Japan.Footnote 103 Although Thompson’s call for land share failed to convince the politicians inside the Anglosphere, it demonstrated that the logic of Malthusian expansionism was widely accepted even among the most educated minds in the West in the early twentieth century.

Germany and Italy also joined the global competition in colonial expansion in the second half of the nineteenth century, and the German and Italian empire builders shared their Japanese counterparts’ predicament. They pointed to Malthusian expansionism as a justification for their efforts to carve out extra “living spaces” for their empires within a world of increasingly shrinking possibilities. Like it was for the Japanese empire, the emigration of “surplus” subjects into sovereign nations was a vital strategy for the German and Italian empires in their quest for wealth and power. Not surprisingly, the German and Italian emigration to other sovereign nations had profound ideological and institutional connections with the territorial expansion of these two colonial empires.Footnote 104 The convergence of the “battle for births” and “battle for land” of Germany and Italy culminated in the rise of fascist imperialism.Footnote 105 In the 1930s, like the Japanese demand for Manchuria as the empire’s “lifeline,” the push for Lebensraum and Spazio vitale eventually became the two fascist regimes’ justification for wars.

Influential Western scholars like Walter Prescott Webb, who became the president of the American Historical Association in 1958, continued to embrace Malthusian expansionism after World War II in their grand narratives of modern world history. Webb saw the US westward expansion as part of the global expansion of Western civilization since the sixteenth century. The lands and seas outside of Europe, which he termed in general as the Great Frontier, did not merely save a static Europe plagued by overpopulation and poverty. The multiple forms of wealth in the Great Frontier, Webb argued, also furnished the further growth of population and the development of capitalism, individualism, and democracy, which he saw as the essential components of Western civilization.Footnote 106

Nevertheless, in the few decades following World War II, the discourse of Malthusian expansion itself had gradually fallen out of favor around the globe. As large-scale international migration and global land share schemes remained elusive in a world of nation-states, the biopolitics of fertility and mortality began to dominate intellectual debates on overpopulation and its solution.Footnote 107 Right after the war, US policy makers were convinced that overpopulation was a cause of Japanese militarism. The promulgation of the Eugenic Protection Law of 1948 in Japan, endorsed by the US occupation authorities, turned postwar Japan into one of the first countries in the world to legalize abortion.Footnote 108 What’s more, groundbreaking technologies had divested land of its absolute primacy in food production.Footnote 109 The condition of overpopulation could no longer fully justify a nation’s demand for additional land or emigration outlet, thus Malthusian expansionism disappeared from intellectual debates and political discourses around the world.

Chapter Overview: The Four Phases of Malthusian Expansionism

Malthusian expansionism in Japan evolved in four phases—emergence, transformation, culmination, and resurgence. In every stage, responding to specific social tensions within domestic Japan and the empire’s interactions with its Western counterparts, Japanese Malthusian expansionists hailed men and women of distinct social strata in the archipelago as ideal subjects for emigration. Specific locations across the Pacific also emerged in each phase as ideal places for these migrants to put down the roots of the empire. Accordingly, this book examines each of these phases by following a chronological order.

Chapters 1 and 2 focus on the formative period of Malthusian expansionism, from the very beginning of the Meiji era to the eve of the Sino-Japanese War in the mid-1890s, and examine the international and domestic contexts in which Malthusian expansionism emerged in the archipelago. By defining the home archipelago as overpopulated while Hokkaido as conveniently empty, the Meiji government justified its policy of shizoku migration as a way to balance domestic demography and a strategy to turn these declassed samurai into the first frontiersmen of the empire. Japan’s imitation of Anglo-American settler colonialism in Hokkaido also inspired the Japanese expansionists to turn their gaze to the American West as an ideal target of shizoku expansion in the 1880s. The blunt white racism that Japanese settlers and travelers encountered in California, however, forced the Japanese expansionists to shift their focus to the South Seas, Hawaiʻi, and Latin America. In their imaginations, these areas remained battlegrounds of racial competition in which the Japanese still had chances to claim a share, and the declassed samurai in the overpopulated archipelago were the ideal foot soldiers in this fight.

Unlike in Hokkaido and the American West, shizoku migration to the South Seas, Hawaiʻi, and Latin America failed to materialize on a significant scale. The decline of shizoku as a social class itself brought Japanese Malthusian expansionism to its second phase that lasted from the mid-1890s to the mid-1920s, examined in chapters 3, 4, and 5. These chapters detail how the focus of Japanese expansionists returned to North America when they replaced shizoku with the urban and rural commoners (heimin) as the backbone of the empire. These chapters also explain how the Japanese struggles against white racism in the US West Coast and Texas set the agendas for Japanese expansion in Northeast Asia, the South Seas, and South America and turned farmer migration into the most desirable model of Japanese settler colonialism in the following decades.

Following a series of domestic and international changes around the mid-1920s, Japan’s migration-driven expansion entered its heyday phase that lasted through the end of World War II, examined in chapters 6 and 7. Two aspects distinguished Japanese Malthusian expansionism in this phase from the previous decades. First, the Japanese government involved itself in migration promotion and management on an unprecedented scale at both the central and prefectural levels, giving rise to “the migration state.” Second, most Japanese expansionists who had been pursuing a seat for Japan in the club of Western empires were left severely disillusioned by the Immigration Act of 1924. They turned to an alternative model of settler colonialism to challenge Anglo-American global hegemony, marked by the principle of coexistence and coprosperity on the one hand and the emigration of grassroots farming families from rural Japan on the other. This new model was first carried out in Brazil and then applied to Japanese expansion in Manchuria and other parts of Asia during the 1930s and 1940s.

The collapse of the empire at the end of World War II brought an abrupt end to Japanese colonial expansion, but the institutions in charge of previous migration campaigns largely remained intact during the US occupation. Chapter 8, also the final part of this book, analyzes the unexpected resurgence of Japanese Malthusian expansionism during the 1950s and 1960s. This was also the final phase in its history. Policymakers and migration leaders, many of whom had led and participated in Japanese expansion before 1945, saw the returnees from the former colonies of the empire – as well as others who lost their livelihood due to the war – as the new nation’s surplus people. Utilizing pre-1945 migration institutions and networks, they were able to restart Japanese migration to South America right after the enactment of the Treaty of San Francisco. In the 1960s, Japanese overseas emigration quickly declined as a rapid growing economy enabled its domestic society to accommodate most of the Japanese labor force. Malthusian expansionism eventually lost its material ground in the archipelago.

To grasp the complexity and dynamics in the relationship between demography and expansion and between emigration and settler colonialism in Japanese history, we must start our story from the very inception. It is with the Japanese colonial expansion in Hokkaido in early Meiji that our story shall begin.