Malthusian expansionism emerged in the Japanese archipelago during the nascent empire’s colonization of Hokkaido in early Meiji. Taking place when the nation-state itself was still in formation, the colonial expansion in Hokkaido constitutes the beginning chapter in the history of the Japanese empire. It not only offers a unique lens to look at the convergence between the process of nation making and that of empire building but also reveals the inseparability between migration and colonial expansion. To build a modern nation, the Meiji government abolished the Tokugawa era’s status system and started turning the social structure into a horizontal one. By 1876, the samurai or shizoku, who were at the top of the Tokugawa social hierarchy, had lost almost all of their economic and political privileges. The government also implemented the policy of developing industry and trade (shokusan kōgyō) in order to boost the national economy, hiring American and European specialists to formulate concrete plans to modernize Japan’s political and economic infrastructure. At the same time, the Meiji leaders were well aware that domestic changes alone were not sufficient to secure Japan’s independence in the world of empires. To be admitted into the ranks of Western powers, Japan needed to have its own colonies. Hokkaido, the island in the northeast that had been a constant object of exploitation by forces in Honshu since the late Tokugawa period, was an easy target.

The Meiji empire’s settler colonialism in Hokkaido was carefully modeled after the British settler colonialism in North America and the US westward expansion. Such imitation turned the specific social and political contexts in early Meiji into a cradle of Malthusian expansionists. Like their predecessors on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean who demanded colonial expansion in North America through the discourse of Malthusian expansionism, the Meiji expansionists rationalized colonial migration in Hokkaido by voicing the anxiety of overpopulation and calling for population growth at the same time. By a stroke of irony, this colonial imitation also inspired the Meiji expansionists to envision the American West as one of the first targets of Japanese expansion in the 1880s and 1890s.

The Shizoku Migration and the Anxiety on “Surplus People”

In 1869, the Meiji government established the Hokkaido Development Agency (Kaitakushi) to manage the colonization of Hokkaido. After Kuroda Kiyotaka took charge in 1871, the agency monopolized almost all political and financial policy-making powers in Hokkaido until its abolition in 1882. Kuroda was originally a samurai of lower rank in the Satsuma domain who held a profound interest in the West, and his empathy for shizoku and his passion for modernizing the nation according to the Western model came together in his blueprint for Hokkaido colonization. Kuroda regarded Hokkaido as a land of promises that would provide immediate help to the imperial government on two of its most urgent tasks: resettling the declassed samurai and developing its economy. He believed that the land of the island was large enough for the government to distribute to the declassed samurai settlers and that Hokkaido could provide enough natural resources to boost the entire nation’s economic development. These two missions thus converged in the colonial migration of shizoku to Hokkaido under the direction of the Development Agency.

The two flagship migration programs launched by the Development Agency were the farmer-soldier program (tondenhei) and the program of land development (tochi kaitaku). The farmer-soldier program recruited domestic shizoku as volunteer soldiers and settled them in Hokkaido by providing free land, houses, as well as other living and farming facilities.Footnote 1 These settlers were expected to conduct both military training and working the land in assigned settlement locations. The program of land development, on the other hand, encouraged nonmilitary shizoku settlement in Hokkaido by providing free lease of land between about one and a half to three chō to each shizoku household up to five years. If their farming proved successful, the shizoku settlers could own the land for no charge.Footnote 2 These policies led to a wave of collective settlements of the declassed shizoku that were financially sponsored by their former lords. These collective projects were usually launched and organized by private migration associations. Though different in format, both programs aimed to export the impoverished shizoku to Hokkaido and turn them into an engine for colonial development.

The programs of shizoku migration to Hokkaido considered both the migrants and the land of Hokkaido itself to be invaluable national resources. Through migration, the policymakers aimed to turn the declassed samurai into model subjects of the new nation and trailblazers in its frontier conquest. The land of Hokkaido was imagined as a source of great natural wealth, and the policymakers expected to convert this wealth into strategic economic resources through the boundless energy and massive manpower of the shizoku migrants.

Though Hokkaido was described as an empty, untouched land, justifying the proposal of migration was not an easy task for the early Meiji leaders. Government official Inoue Ishimi, for example, observed in 1868 that the size of the existing population in Japan proper was limited, and most of the residents shouldered the responsibility for providing food to the entire country. Unless its agricultural productivity increased, he believed, the nation could not afford to send people to Hokkaido.Footnote 3 The concern about population shortage in Japan proper was further voiced by Horace Capron, the American advisor hired by the Japanese government to guide this colonial project. Based on his investigation, Capron reported to the Meiji government in 1873 that even within Japan proper, only half of the land was occupied and explored.Footnote 4

While both Inoue and Capron were supporters of Hokkaido migration, they considered the domestic population shortage a barrier and believed that it was necessary to have a surplus population in Japan proper first. They both mentioned that modernizing agricultural technology would free some labor from food production. However, such developments still could not provide the timely source of migration that the state immediately needed. A solution was found, instead, by reinterpreting demography. Based on the assumption that a certain size of land has a maximum number of people that it can accommodate, a document issued by the Meiji government in 1869, Minbushōtatsu (Paper of the Ministry of Popular Affairs), defined the existing population distribution in the nation as imbalanced, with an excess in Japan proper, where most areas were so densely populated that there was not even “a place to stick an awl” and a shortage in Hokkaido and other peripheries where the spacious land was in dire need of human labor.Footnote 5 This imbalance, the report claimed, led to surplus people and their poverty. To allow for existing resources to be used more evenly, these redundant people in overpopulated areas had to migrate to unpopulated areas to utilize unexplored land.Footnote 6 Therefore, the uneven distribution of the Japanese population, defined by this report, provided the logical ground for the government-sponsored shizoku migration programs to Hokkaido.

The Birth of Demography and the Celebration of Population Growth

The idea of seeing the empty land of Hokkaido as a cure for domestic poverty was by no means new. Tokugawa intellectuals like Namikawa Tenmin had used it to rationalize their proposals for northward expansion as early as the eighteenth century.Footnote 7 However, the discourse of overpopulation that emerged in early Meiji was a direct result of Japan’s embrace of the modern nation-state system and New Imperialism in the nineteenth century. The government report of 1869 that investigated and interpreted the demographic figures in the archipelago was a result of the Meiji leaders’ efforts to make information about people, society, and natural resources visible to the state through quantitative methods.

As it did in Europe and North America, demography as a modern discipline emerged in Japan as a critical means for the government to both monitor and manage the life and death of its subjects.Footnote 8 A central figure behind the push for state expansion in population management during the Meiji era was Sugi Kōji. Growing up in late Tokugawa Nagasaki and trained in Dutch Learning (Rangaku), Sugi first encountered the discipline of statistics while translating Western books into Japanese for the Tokugawa regime. He was particularly impressed by data books of social surveys conducted in Munich in the Kingdom of Bavaria.Footnote 9 Sugi started working for the Meiji government in 1871 as the head of the newly established Department of Statistics (Seihyō Ka), the forerunner to the Bureau of Statistics. In 1872, based on information collected by the national household registration system it had recently established, the Japanese state began to regularly conduct nationwide population surveys.

However, unsatisfied with this type of survey, Sugi conducted a pilot study in 1879 on demographic data in the Kai region in Yamanashi prefecture that was modeled on censuses conducted in Western Europe. This study was the first demographic survey in Japan that was based not on household registration but on individuals’ age, marriage status, and occupation.Footnote 10 After spending two years calculating and analyzing the collected data, Sugi publicized the survey results in 1882. He urged the Meiji government to conduct a national demographic survey modeled after this pilot study in order to produce high-quality census data like those in Europe and North America.Footnote 11 However, an enormous government budget cut by Minister of Finance Matsukata Masayoshi made Sugi’s proposal impractical for the time being. In 1883, Sugi left his government post to cofound the School of Statistics (Kyōritsu Tōkei Gakkō), a private institution training students in quantitative methods using German textbooks.Footnote 12 Although the school was shut down amid the Matsukata Deflation, its pupils would go on to spearhead the Empire of Japan’s first census, conducted in Taiwan in 1905.Footnote 13

A central motive behind the quest for demographic knowledge in Meiji Japan was to provide scientific evidence to confirm the commonsense observation of rapid population growth in the archipelago at the time, a phenomenon brought on by the modernization of medicine and public hygiene. Japanese intellectuals, like their Western counterparts since the Age of Enlightenment, interpreted demographic expansion as a symbol of progress and prosperity. Since the size of population was considered a direct indicator of a nation’s military strength and labor capacity, its increase was widely celebrated in the archipelago as Japan was finding its feet in the social Darwinist world order. More importantly, the celebration of population growth in Japan, as it was in the West, took place in the context of modern colonialism. Joining hands with the claim of overpopulation, it legitimized the Japanese empire’s quest for wealth and power overseas. The necessity for population growth on the one hand and the anxiety over the existence of surplus people on the other hand formed the central logic of Malthusian expansionism that justified Japan’s migration-driven expansion throughout the history of the Japanese empire.

This logic was well elaborated in the writings of the prominent Japanese enlightenment thinker Fukuzawa Yukichi at the end of the nineteenth century. According to the rule of biology, Fukuzawa argued, a species always had a quantitative limit to its propagation within a certain space. “There is a cap on how many golden fish can be bred in a pond. In order to raise more, [the breeder] either needs to enlarge the pond or to build a new one.” The same was true, he argued, for human beings. While thrilled by the demographic explosion in the archipelago of the day, Fukuzawa warned that with such a speed of growth, the Japanese population would soon reach the quantitative limit set by Japan’s current territory and stop reproducing. However, population growth, Fukuzawa also reminded his readers, was crucial for a nation’s strength and prosperity. No nation, he argued, could achieve substantial success with an insufficient population. A nation had to maintain its demographic growth because demographic decline would lead only to the decline of the nation itself.Footnote 14

Inspired by Anglo-American settler colonialism in the recent past, Fukuzawa concluded that the only solution to Japan’s crisis of overpopulation was emigration. Although the domestic population of England was even smaller than that of Japan, he reasoned, the British Empire enjoyed the unmatched prestige and power around the world thanks to the vibrant productivity of the Anglo-Saxon race. The limited space in the British Isles pushed the Anglo-Saxons to leave their home country and conquer foreign lands. The Japanese, Fukuzawa believed, should follow the British example by building their own global empire.Footnote 15

Malthusian Expansionism and Japanese Settler Colonialism in Hokkaido

As the thoughts of Fukuzawa Yukichi also revealed, Malthusian expansionism was originally an Anglo-American invention. It was first transplanted into the Japanese soil by Meiji leaders during Japan’s colonial expansion in Hokkaido. The following paragraphs examine how Malthusian expansionism took root in the social and political contexts of late nineteenth-century Japan and was used to legitimize the colonization of Hokkaido, the first colonial project in the Japanese empire. This initial phase of Japanese Malthusian expansionism also provides a valuable lens to look at how Japanese empire builders modeled the colonial expansion in Hokkaido in early Meiji after Anglo-American settler colonialism. This imitation can be revealed in three aspects, including the settlement of shizoku, the acquisition of Ainu land, and the accumulation of material capital. Together these three aspects further explain how the call for population growth worked in tandem with the complaint of overpopulation to legitimize Japanese setter colonialism in Hokkaido.

Making Useful Subjects: Shizoku as Mayflower Settlers

While the Meiji government defined imbalanced demographic distribution as the cause of poverty and argued that relocating the surplus people to Hokkaido would lift them from destitution, the majority of the selected migrants were not those who lived in absolute poverty but the recently declassed samurai. The abolition of the status system deprived them of their previous affiliations and transferred the loci of their loyalty from individual lords to the Meiji nation-state itself.Footnote 16 Losing almost all inherited privileges and lacking basic business skills, the shizoku were pushed to the edge of survival. These politically conscious shizoku, who struggled for both economic subsistence and political power in the new nation, posed a serious challenge to the safety of the early Meiji state from both within and without. The angry shizoku formed the backbone of a series of armed uprisings in the 1870s that culminated in the Satsuma Rebellion in 1877 and the Freedom and People’s Rights Movement spanning from 1874 to the 1890s.

Instead of perceiving the struggling shizoku solely as a burden or threat, Meiji intellectuals and policymakers believed that they could be put to better use. The question of how to resettle these potentially valuable subjects – and to some extent restore their leadership in the new nation – remained a central concern of Meiji policymakers and a hot topic in public debate until the 1890s. The idea of personal success (risshin shussei), which would later grow into a dominant and persistent discourse of overseas expansion in Japanese history, emerged at this particular moment. Risshin shussei was invented initially to provide alternative value systems for the declassed samurai. In his popular book Saikoku Risshi Hen (an adapted translation of Self-Help, a best seller in Victorian Britain by Samuel Smiles), Nakamura Masanao (Keiu) told his shizoku readers that their accomplishments and advancements in society should come not from inherited privileges but from their own virtues such as diligence, perseverance, and frugality.Footnote 17 Whereas the road to success proposed by Nakamura remained abstract and spiritual, another route, promoted by Fukuzawa Yukichi, was specific and pragmatic. In his widely circulated book Gakumon no Susume (Encouragement of Learning), Fukuzawa argued that learning practical knowledge (jitsugaku) should be the way for shizoku to regain their power. Specifically, it was knowledge in Western learning, achieved through education, that would give them wealth and honor in the new Japan. The independence of shizoku would then lead to the independence of Japan in the world.

One of the most influential promoters of shizoku success was Tsuda Sen, whose career demonstrated the intrinsic ties between the discourse of shizoku independence and that of national prosperity. Born into the family of a middle-rank samurai, Tsuda acquired English proficiency through education and visited the United States in 1867 as an interpreter on a diplomatic mission for the Tokugawa regime. Impressed by the critical role of agriculture in fostering American economic growth and westward expansion, he began a lifelong career in Westernizing Japan’s agriculture. Shortly after the formation of the Meiji nation, he founded the Agriculture Journal (Nōgyō Zasshi), a widely circulated magazine that disseminated the knowledge of Western agricultural science and advocated the importance of agricultural production. A nation’s independence, he argued in the opening article in the inaugural issue, could be achieved only when the production of the nation became sufficient so that exports exceeded imports.Footnote 18 He also established a school, the Society of Agriculture Study (Gakunō Sha), to train shizoku in practical farming skills. He sought to overcome shizoku’s traditional contempt for farming and persuade them to “return to agriculture” (kinō) with Western technologies and become “new farmers” (shinnō) of the new nation.Footnote 19 He firmly believed that the modernization of agriculture would restore shizoku’s honor and wealth as well as further enable Japan to find its footing on the social Darwinist world stage.

Tsuda’s initiative matched well with the Meiji government’s policy of shizoku relief (shizoku jusan) that aimed to help the declassed samurai to achieve financial independence while turning them into productive subjects of the nation.Footnote 20 Tsuda himself played a central role in promoting shizoku migration to Hokkaido. With the support of Kuroda Kiyotaka, Tsuda founded the Hokkaido Kaitaku Zasshi (HKZ, Hokkaido Development Journal) in 1880. This journal served as the mouthpiece of the Hokkaido Development Agency to the general public, promoting its migration programs by linking the individual careers of shizoku with the colonial development of Hokkaido. Though it was decidedly short-lived (it folded after two years due to the agency’s demise),Footnote 21 this biweekly journal provides a valuable lens to look at how the idea of making useful subjects worked together with Malthusian expansionism to foster shizoku settlement in Hokkaido.

In an editorial, Tsuda reasoned that the peasant population in Japan already exceeded what the existing farmland in Japan proper could accommodate. At the same time, there were many newly declassed samurai who had to turn to farming for their livelihood. Relocating them to Hokkaido served as a perfect solution to the issue of farmland shortage.Footnote 22 The natural environment of Hokkaido, Tsuda also reminded his readers, was demanding. For Japanese pioneers in Hokkaido, it was extremely difficult to carve out a livelihood in the wilderness. They had to be resolute in the face of such enduring hardships if they were to achieve any measure of success.Footnote 23 The fact that Nakamura Masanao’s essay appeared in the first issue of the journal demonstrated the importance of the ideology of shizoku self-help as a driving force behind the Hokkaido migration. Nakamura, who enthusiastically applauded Tsuda Sen’s efforts, argued that Hokkaido was an ideal place for those who had no land or property to achieve success through their own hands.Footnote 24

Though Tsuda used the opportunity for personal success to encourage shizoku individuals to migrate, it was the prosperity of the Japanese empire that gave the Hokkaido migration its ultimate meaning. Tsuda took pains to use the legend of the Mayflower Pilgrims to encourage shizoku migrants to connect their lives with the very destiny of the Meiji empire. Conflating the story of the Pilgrims and that of the Puritans during the British expansion in North America, Tsuda described how the Mayflower “Puritans” risked their lives to sail across the Atlantic Ocean to North America in order to pursue political and religious freedom due to persecution in their homeland. Not only was their maritime journey long and often deadly, the initial settlement in the new land was also challenging. In Tsuda’s narrative, after enduring every kind of shortage imaginable (food, farming equipment, fishing and hunting tools), the “Puritan” settlers eventually survived. They overcame all these difficulties and turned the barren earth of America into an invaluable land of resources. It was the efforts of these earliest settlers, Tsuda argued, that established the foundation of the United States as one of the most prosperous nations in the world.

For Tsuda, the situation of shizoku was reminiscent of the persecuted Mayflower settlers in that they were deprived of inherited privileges. Like the “Puritans” who sailed to America for political rights and religious freedom, the shizoku were supposed to regain their honor and economic independence by migrating to Hokkaido. The success of the Mayflower settlers, therefore, served as a model for the shizoku migrants. Resolved to overcome extreme difficulties and carve out the path for the future empire builders in Hokkaido by sacrificing their own lives, the shizoku migrants could make their achievements as glorious as their British counterparts.Footnote 25

The Loyal Hearts Society (Sekishin Sha), a migration association established in 1880 in Kobe, aimed to relocate declassed samurai to Hokkaido. Tsuda applauded it as a success in emulating the example of the Mayflower settlers. The prospectus of the society argued that it was more meaningful for shizoku to find ways to live a happy life than to simply waste their time complaining about their dire conditions. Among all the paths to success, it claimed, the “exploration of Hokkaido” was the most effective and realistic choice. More importantly, participating in the exploration would allow these poor shizoku to associate “their small and humble life with great and noble goals” since their personal careers would sway the fate of the empire.Footnote 26 The regulations of the society further required them to prepare for permanent settlement in Hokkaido, building it both for their descendants and for the empire. For Tsuda, the members of the society further served as living examples of how common Japanese subjects should take on their own responsibilities for the nation.Footnote 27

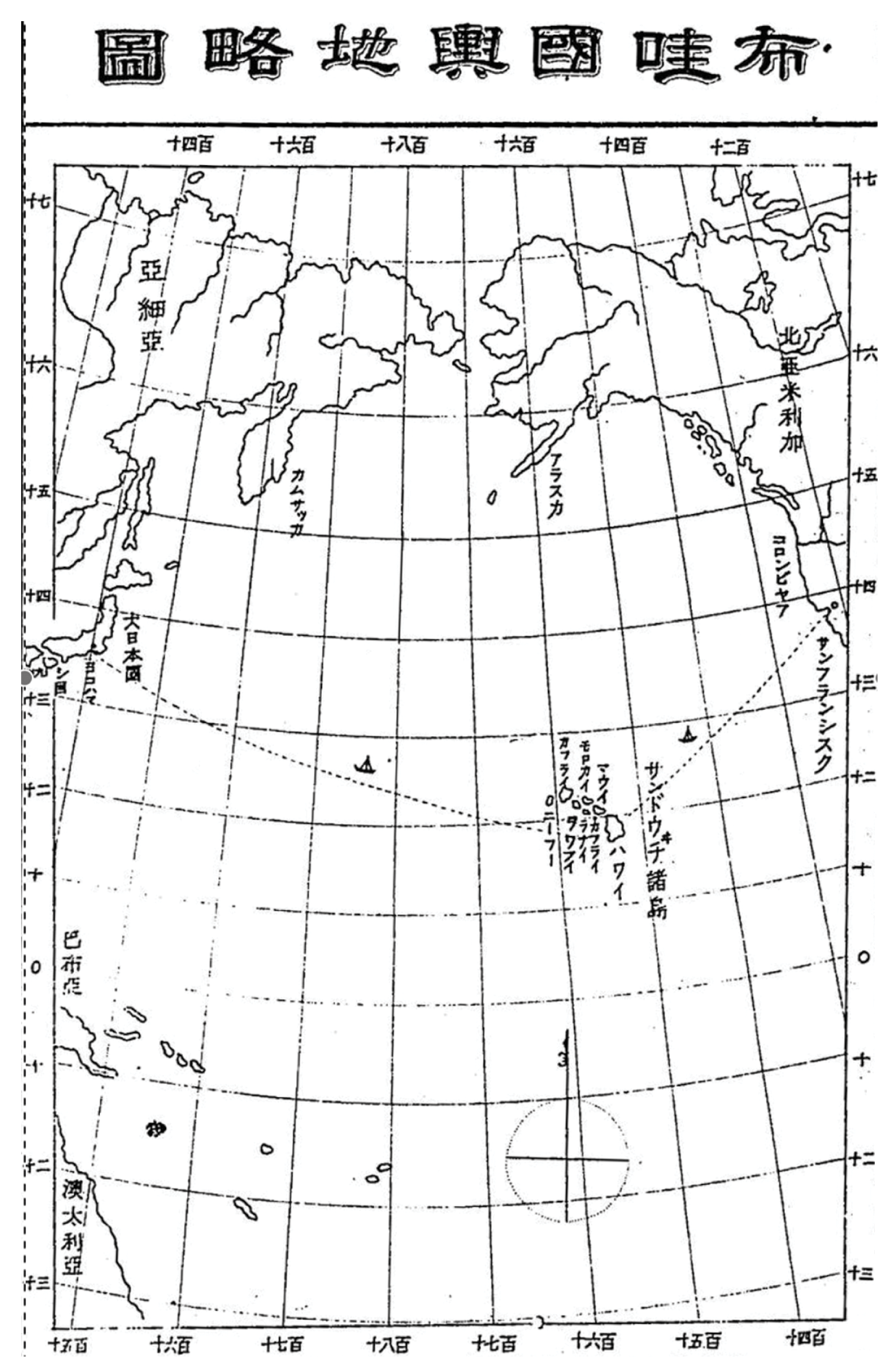

Figure 1.1 This picture appeared on the second issue of Hokkaido Kaitaku Zasshi. The caption reads, “The picture of the Puritans, the American ancestors, who landed from the ship of Mayflower and began their path of settlement.” HKZ, February 14, 1880, 1.

Acquiring the Ainu Land via the Mission Civilisatrice: Ainu as Native Americans

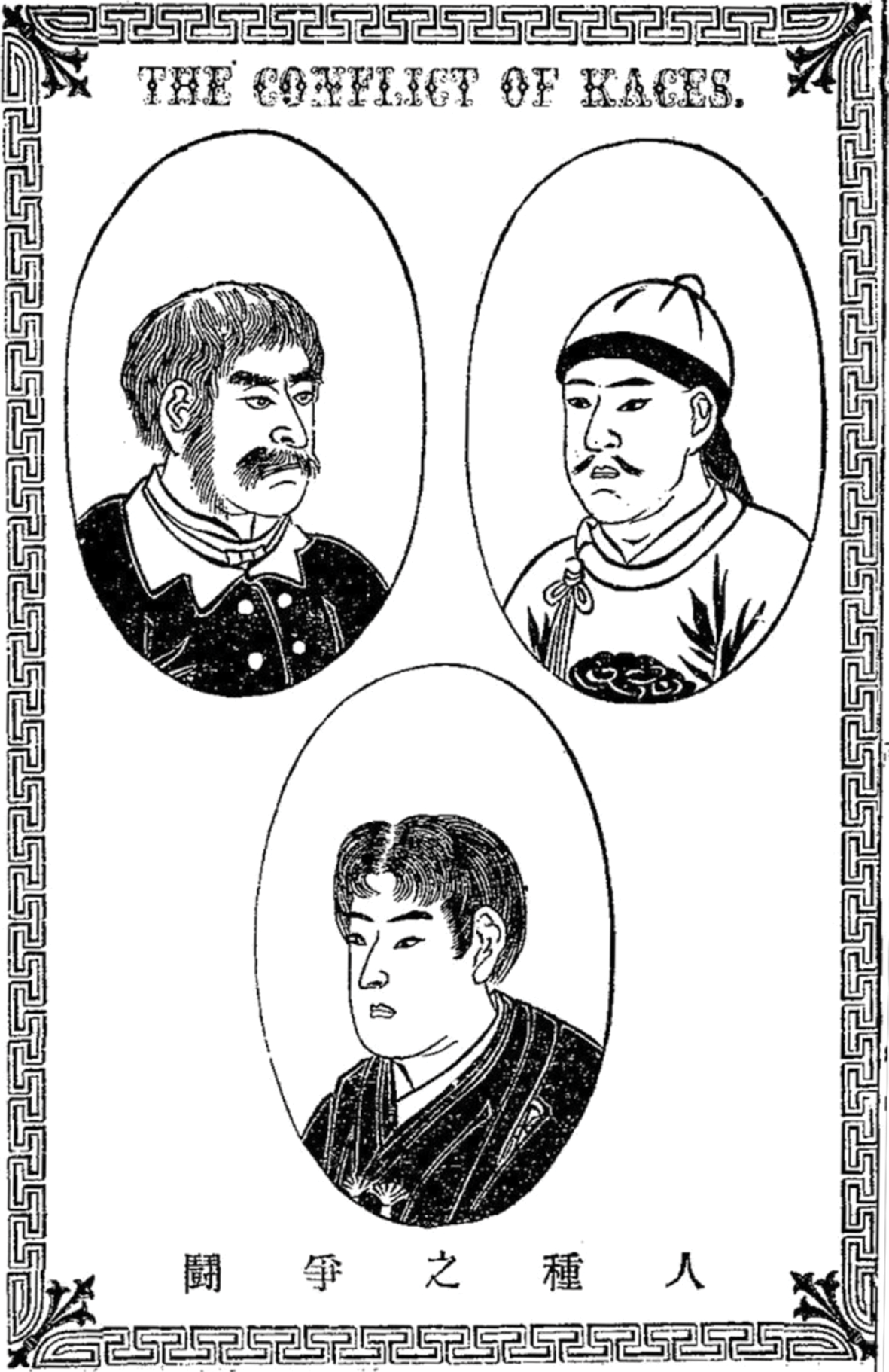

If overpopulation in Japan proper legitimized the relocation of declassed shizoku, the growth of Japanese population served as a justification for the Meiji empire to acquire and appropriate the land of Hokkaido, originally occupied by the Ainu. In the writings of demographers and economists in early Meiji, the Japanese were listed as one of the most demographically expanding races in the world. In particular, the rapid increase of the Japanese population was considered to be proof that the Japanese were a superior race, equal to the Anglo-Saxons.Footnote 28 The image of the Japanese as a growing and thus civilized race was further solidified by being juxtaposed against the image of the disappearing Ainu natives in Hokkaido.Footnote 29 The discourse of Japanese growth and Ainu decline in Hokkaido drew parallels with the growth of the white settlers and the decline of the Native Americans in North America.Footnote 30 Through this comparison, not only were the Japanese grouped with the Europeans as the civilized, but the decrease of the Ainu was also understood as natural and unavoidable in the social Darwinist world.

Such a comparison mirrors the British explanation for the expansion of the English settlers in North America in contrast to the quick decline of the Native American population in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. British expansionists attributed the divergence in the demographic trends of the British settlers and the Native Americans to the physical and cultural superiority of the former over the latter.Footnote 31 Ignoring the fact that the fall of the Native American population was mainly the result of European epidemics brought by the settlers to the new land, Thomas Malthus believed that the savageness of the Native Americans, too, functioned as a check to keep the growth of their population within the capacity of the food supply. On the other hand, the demographic growth of the British settlers was a result of their superior manners and the abundance of room in the New World.Footnote 32

The ideas of Thomas Malthus later inspired Charles Darwin to establish his theory of evolution, which explained the different fates of species as a result of natural selection.Footnote 33 The application of Darwinism in the understanding of human history and societies gave rise to modern racism that undergirded the existing discourse of racial hierarchy in the European colonial expansion through scientific reasoning. Faithful subscribers to social Darwinism, Meiji leaders, too, believed that only the superior races could enjoy a high speed of population increase while the inferior peoples were heading down a path of inexorable decline and eventual extinction. The destiny of the inferior races was sad but unavoidable because, due to their backwardness, they were not capable either to achieve social stability and community growth from within or to compete with the superior people from outside who came to colonize their lands.Footnote 34

The demography-based racial hierarchy between the Japanese and Ainu further justified the Meiji leaders’ appropriation of the Ainu land through the Lockean logic of land ownership. Like their European counterparts, the Meiji expansionists believed that the superior and the civilized had the natural right to take over the land originally owned by the inferior and the uncivilized so that the land could be better used. Therefore, it is not surprising that Kuroda Kiyotaka appointed Horace Capron, then the commissioner of agriculture in the US government, as the chief advisor of the Hokkaido Development Agency. Before working in the US Department of Agriculture, Capron was assigned by US president Millard Fillmore to relocate several tribes of Native Americans after the Mexican-American War.Footnote 35 Capron himself, while investigating the land of Hokkaido, found close similarities between the primitive Ainu and the savage Native Americans.Footnote 36

For this reason, the migration from Japan proper to Hokkaido, the land of Ainu, was not only a solution to the issue of overpopulation in Japan but also an act of spreading civilization and making better use of the land itself. In the very first editorial of the Development Journal, Tsuda tried to convince his readers that Hokkaido of the day was no longer the land of Ezo. The existing understanding of Hokkaido, Tsuda argued, was based on the book The Study of Ezo (Ezoshi), which was authored by Confucian scholar Arai Hakuseki one and a half centuries earlier. It described the island as a sterile land with only a few crooked roads. However, Tsuda continued, times had changed. The time had come for the Japanese to reunderstand Hokkaido as a land of formidable wealth, where settlers from Japan proper could farm, hunt, and engage in commerce. Such a transition would be a result of the Japanese government’s transplantation of civilization to the island.Footnote 37 The native Ainu saw their ancestral lands taken away from them due to their supposed “lack of civilization,” and the land of Hokkaido was redefined by the Development Agency as unclaimed land (mushu no chi) based on the Hokkaido Land Regulation of 1872, thereafter distributed to the shizoku settlers.Footnote 38

The logic that the civilized had the right to take over the land of the uncivilized so that it could be better used was more explicitly articulated in an article in the Development Journal discussing a coercive Ainu relocation. In order to secure the control of Hokkaido, the Meiji government signed the Treaty of Saint Petersburg with the Russian Empire in 1875, recognizing Russian sovereignty over Sakhalin Island in exchange for full ownership of the Kuril Islands. Ainu residents in Sakhalin were, of course, excluded from the negotiation process. About 840 of them were forced to migrate from the Sakhalin Islands to Tsuishikari, a place close to Sapporo.Footnote 39 Though Tsuda recognized the unwillingness of these Ainu to give up their homeland and admitted that the forced relocation had caused them grief, he contended that such pain was necessary: Since the Ainu lacked both motivation and ability to develop their Sakhalin homeland into a profitable place, it would be a waste to let them stay there in hunger. The Japanese, on the other hand, not only put Sakhalin to better use by exchanging it for the Kuril Islands with Russia, but also had been civilizing these relocated Ainu. Tsuda happily noted that the Ainu in Tsuishikari, in addition of receiving new educational opportunities, were learning the modern ways of hunting, handcrafting, and trading. He posited that these Ainu were now satisfied with their new life and felt grateful for the protection offered by the Development Agency.Footnote 40 By this logic, the Meiji government’s takeover of Ainu lands was portrayed as an altruist project that had the native residents’ best interests at heart.

In reality, however, the relocation soon trapped these Ainu in misery. Unfamiliar with the new environment and incapable of adapting to the new ways of production introduced by the Meiji authority, they could not sustain their own livelihood. The community was further decimated by epidemics. Especially in 1886, the spread of smallpox claimed over three hundred lives. Many survivors later returned to Sakhalin.Footnote 41 The tragedy of this group of Ainu was only an example of the rapid decline of Ainu communities in general due to a series of Meiji policies that deprived them of their land, materials, and cultures in the name of spreading civilization.Footnote 42

Accumulating Material Capital: Hokkaido as California

Meiji expansionists’ acclamation of population growth was also a product of the development of Japan’s nascent capitalist economy. Their desires to acquire more human resources as well as natural resources were driven by the impulse of capitalist accumulation. The migration of people from Japan proper to Hokkaido to explore and exploit the natural resources was to meet these demands. In their imaginations, the worthless land of yesterday’s Ezo suddenly became a precious source of ever-growing wealth (fugen), because its earth, rivers, mineral deposits, plants, and wild animals all became potential resources for Japan’s nascent capitalist economy.

In the eyes of Tsuda Sen, the enormous amount of natural wealth in Hokkaido was vital to finance industrialization, road building, and trade expansion of the Japanese empire.Footnote 43 To help readers in Tokyo understand the richness of Hokkaido through the vocabularies of capitalism, almost every issue of the Development Journal included articles that illustrated how various natural resources in Hokkaido could be either extracted for direct profit or used for material production. These included, to name but a few examples, tips for hemp processing, benefits of planting potato, knowledge of running winery, and methods of salmon hunting.Footnote 44

For the Meiji empire’s capitalist exploitation of Hokkaido through migration, the American westward expansion served as a key guide. The director of the Development Agency, Kuroda Kiyotaka, appointed Horace Capron, the commissioner of agriculture in the US government, as the main advisor to the Development Agency. The agency also hired more than forty other American experts who specialized in agriculture, geology, mining, railway building, and mechanical engineering to guide its project of transforming natural deposits in Hokkaido into profitable resources.Footnote 45

To draw the parallel between Japanese colonial migration in Hokkaido and American westward expansion, Tsuda Sen declared that soon an “America” would emerge from the Japanese archipelago. While Japan currently could not compete with America in terms of wealth, power, and progress in democracy and education, he maintained, the soil of Hokkaido was as rich as that of the United States, and their climates were equally suitable for farming. Tsuda assured his readers that as the colonial project continued to develop, material production from Hokkaido would match that in the United States.Footnote 46 In particular, he compared the position of Hokkaido in Japan to that of California in the United States. Located on the West Coast of North America, Tsuda argued, California had been no more than an empty land until it became a part of America. Within two decades of American settlement, with the discovery of gold and improvements to agricultural technology, its population and material products grew exponentially. Hokkaido, Tsuda claimed, had not only similar latitudes to California but also equal amounts of natural resources. With the influx of settlers from Japan proper making progress in land exploration, the Ezo of yesterday would surely become the California of tomorrow. It would serve as a permanent land of treasure for Japan, the output of which would sustain Japan’s economic growth at home and bring in wealth from abroad through exportation.Footnote 47

At the center of Japan’s imitation of American westward expansion was the transplantation of American agricultural technology to Hokkaido. Tsuda believed that in addition to the Puritan spirit of the early settlers, the Americans owed much of their triumph to the fertility of its land and a high agricultural productivity. Assuming Hokkaido’s land would prove to be equally fertile, Tsuda concluded that the key to the success of Hokkaido exploration was to increase the existing agricultural productivity by transplanting American technology.Footnote 48 He not only translated several books on new American farming practices from English to Japanese, but also included many articles in the Development Journal calling on farmers to adopt American farming tools and techniques in areas such as crop cultivation, animal husbandry, and pest control. Under the direction of the Development Agency, a variety of American crops, livestock, and machines were introduced and used in Hokkaido. In 1876, the agency established the Sapporo Agricultural College (SAC, Sapporo Nōgakkō) to offer future generations of empire builders advanced agricultural knowledge. It appointed William Clark, the third president of the Massachusetts Agricultural College (now the University of Massachusetts Amherst) in the United States and a specialist in agriculture and chemistry, as the head of SAC for a year. Clark passionately promoted the model of American agriculture in Hokkaido when serving in this position.Footnote 49

The Transformation of Colonial Policies in Hokkaido

The colonial project led by the Development Agency was expensive. From 1872 to 1882, it cost more than 4.5 percent of the national budget each year on average. In 1880, as much as 7.2 percent of total government spending went to Hokkaido.Footnote 50 The extent of the financial support indicated a consensus among the Meiji leaders on the overall strategic direction of the Hokkaido venture: the colonial project should be conducted through state planning and under the government’s political and financial control.

Though the intellectuals were nearly unanimous in envisaging Hokkaido as an enormously profitable colony as well as a land for declassed samurai to find their own feet and prove their value in the new nation, they were divided on how the colonial project should be carried out. Some, like Wakayama Norikazu, a Meiji political strategist and high-ranking official in the Ministry of Agriculture and Commerce, believed that the colonial exploration of Hokkaido should be controlled and protected by the state, which should subsidize the migration of poor shizoku and help them settle down in Hokkaido as landowning farmers.Footnote 51 Others, however, were highly critical of the government’s huge spending in Hokkaido. The liberalist thinker Taguchi Ukichi, the editor of Tokyo Economic News (Tokyo Keizai Zasshi) – one of the most influential newspapers in the Meiji era – was firmly in the latter camp. Attributing the success of British colonial expansion to the principle of free trade, Taguchi urged the Japanese government to cease its intervention in the colonization of Hokkaido. Tokyo Economic News acted as a platform for liberal thinkers to criticize almost every single Development Agency policy. Taguchi believed that Hokkaido exploration of the day was monopolized by the plutocrats in the government. The exclusion of common people from participation in the colonial project and the lack of fair competition, he warned, would eventually lead to the failure of the overall project.

The agency’s sponsorship of the migration programs was a special target for Taguchi. People, he argued, were driven by profits. The temporary subsidy and governmental intervention would lead only to fake achievement, with settlers staying in Hokkaido only to profit from governmental aid. Once the support disappeared, so would the settlers. The successful settlement in Hokkaido, Taguchi argued, should be accomplished by independent individuals who would build a career on their own. He believed that instead of agriculture-based migration, the wealth of Hokkaido’s natural resources should be first tapped by merchant settlers. Taguchi considered the monopoly of natural resources by Kuroda’s plutocrat allies and the high tax rates in Hokkaido as fundamental obstacles for common shizoku to pursue success in Hokkaido by starting businesses of their own.Footnote 52

The criticisms that the Hokkaido Development Agency faced as well as the government budget cuts amid the Matsukata Deflation propelled a liberalist turn for governmental policies in Hokkaido after the agency’s abolishment in 1882. The prefectural government of Hokkaido, established in 1886, placed capital importation at the center of colonial exploration, thereby reversing the agency’s migration-centered approach.Footnote 53 The new policies stimulated inflows of private capital to Hokkaido, leading to the rapid concentration of land ownership in Hokkaido in the hands of private wealthy investors and the formation of a big farm economy similar to the agricultural model in the United States. The implementation of this big-farm model of colonial development was described by colonial thinker Satō Shōsuke as turning Hokkaido into “Japan’s America.”Footnote 54 As a result of the influx of private capital, most of the explored lands in Hokkaido were soon claimed by a small number of wealthy landlords, many of whom lived in Tokyo, while the majority of the local population were turned into agricultural laborers.Footnote 55

The withdrawal of the state intervention opened the doors of Hokkaido to more migrants from Japan proper. Yet the majority of the newcomers since the mid-1880s were poor and landless farmers whose lives were devastated by the Matsukata Deflation.Footnote 56 For colonial thinkers who considered expansion a way to transform shizoku from seeds of instability to model subjects of the nation, Hokkaido was no longer an ideal land because agricultural labor without landownership was not sufficient for these shizoku to gain wealth and honor. New frontiers of expansion beyond the Japanese archipelago were thus needed.Footnote 57 Malthusian expansionism was embraced again to legitimize the proposals of migration overseas, which aimed to export the “surplus people” and in the meantime allow them to connect their personal ambitions with that of the nation. Tsuda Sen investigated the Bonin Islands (Ogasawara Guntō) as a possible place for shizoku migration in 1880.Footnote 58 One year earlier, an article in Tokyo Keizai Zasshi even proposed expansion to Africa.Footnote 59 Yet the agendas of expansion beyond Hokkaido materialized first in Japanese migration to the United States.

From “America in Japan” to “Japan in America”: The Rise of Japanese Trans-Pacific Expansion

I call the campaign of Japanese migration to the United States from mid-1880s to 1889, spearheaded by Fukuzawa Yukichi and his students, the first wave of Japanese migration to the United States. In terms of ideology, this movement was a direct offspring of the shizoku-based colonial expansion in Hokkaido of the previous years. Japan’s imitation of Anglo-American settler colonialism in Hokkaido directly inspired the shizoku expansionists to consider the American West as an alternative to Hokkaido. The imagined similarities between Hokkaido and California also allowed the expansionists to replicate their visions on Hokkaido to Japan’s expansion to the other side of the Pacific.

Though not as vocal as Tsuda Sen, Fukuzawa Yukichi was also a firm supporter of colonial expansion in Hokkaido. He believed Hokkaido’s enormous wealth should be utilized, and he connected shizoku’s personal success with the act of colonial expansion. Some of his students at Keiō School (Keiō Gijuku) participated in the Hokkaido Development Agency’s shizoku-migration program. Among them, Sawa Mokichi served as president of the Loyal Heart Society and Yoda Benzō founded the Late Blooming Society (Bansei Sha), both of which were leading companies in Hokkaido migration of the day.

Fukuzawa shifted his gaze from Hokkaido to the United States for Japanese migration in 1884. In a public speech in that year, he used the example of British setter colonialism in New England to criticize the lack of expansionist spirit among the educated youth in Japan:

Let us suppose that Hokkaido is a British territory. … Its soil is rich, and it has great natural resources. If such a source of wealth were located 500 miles from London, I doubt that the British would ignore it. Certainly, they would compete with each other to settle Hokkaido and to develop the entire island; and then come up with another New England within a few years. … I am very embarrassed. The Europeans crossed five thousand miles of ocean to develop America, while the Japanese refuse to go to Hokkaido because they say that five hundred miles is too great a distance.Footnote 60

In the second half of the speech, after acknowledging the difficulties of the natural and economic conditions in Hokkaido, Fukuzawa proposed, “If Hokkaido is really bad, why don’t our young men change their direction and go to foreign countries?” In particular, he pointed out, “America is the most suitable country for anyone to emigrate to.”Footnote 61 For Fukuzawa, the United States, just like Hokkaido, was a land of abundant wealth awaiting Japanese exploration. As he described in The Review of Nations in the World (Sekai Kuni Zukushi),

[The United States] is equal to Great Britain in every kind of manufacturing and business, and it excels France in literature, arts, and education. Their land produces grains, animals, cotton, tobacco, grapes, fruit, sweet potatoes, gold, silver, copper, lead, iron, coal; indeed, nothing necessary in daily life is wanting. People who want to get clothes and food naturally come to the place where it is easy to make a living, so people gather from all over the world every day and every month.Footnote 62

Not everyone in Japan was qualified to go to the United States, however. Only shizoku, with their education background, talent, and ambition, deserved the right of emigration.Footnote 63 Different from the rural poor who went to Hawaiʻi as contract laborers to survive, the emigrants to the US mainland were given the task of improving Japan’s national image.Footnote 64 As an immigrant nation that had a vibrant spirit of progress and stood at the center of modern civilization, Fukuzawa argued, America was the place where shizoku could study and grow as Japanese subjects.Footnote 65

Moreover, the United States was also an expanding nation that kept on opening up new lands through frontier conquest and migration. Fukuzawa encouraged the Japanese to follow the examples of European settlers and participate in American frontier expansion. A loyal follower of Benjamin Franklin, Fukuzawa also replicated Franklin’s metaphor of polyps for settler colonialism in his own promotion of Japanese trans-Pacific expansion. One day, Fukuzawa expected, the Japanese offspring in the United States would gain political rights and sway American politics. In this way, the overseas migrants would establish ten or even twenty “new Japans” around the world.Footnote 66

If the opportunities of serving the nation, acquiring wealth, and contributing to the progress of civilization were used to encourage shizoku to emigrate to the United States, the logic of Malthusian expansionism turned the migration into an absolute necessity. Although the land of the United States had already been enclosed by its national sovereignty, this fact by no means prevented the Japanese expansionists from having colonial ambitions over the American land. In their imaginations, the Lockean definition of land ownership that justified Anglo-American settler colonialism continued to be applicable to the Japanese settlement in the American West. In a revised Lockean logic, they believed that the territory of the United States was still open to appropriation by others because it was still largely empty and unutilized due to its low occupancy by white settlers. Thus, it was the natural right for the Japanese, civilized people from the overcrowded archipelago to settle in, then claim and make use of the land.

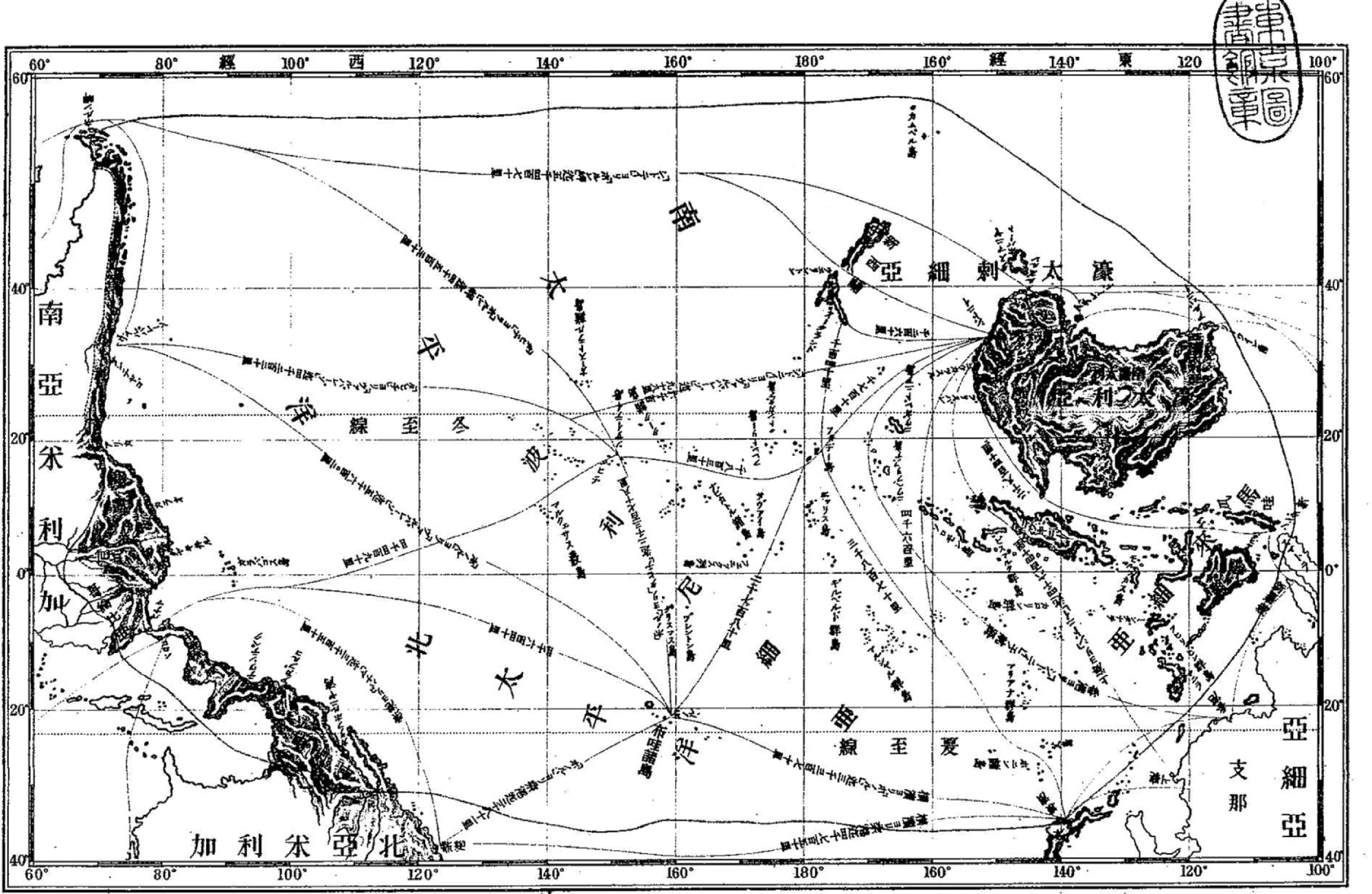

It is no wonder why one of the central promoters of Japanese migration to the United States at this time was the founder of demography in modern Japan, Sugi Kōji, himself. Sugi was also an intellectual friend of Fukuzawa who studied at Tekijuku, a school of Dutch Learning where Fukuzawa previously attended.Footnote 67 While the idea of population imbalance in Japanese archipelago was used to rationalize the migration from Japan proper to Hokkaido, Sugi applied this view in his description of the demography in the world at large. Backed up by demographic data about Japan and other countries in the world he collected, Sugi argued in a speech in 1887 that the overall distribution of people over land in the world was uneven. Therefore, to avoid regional poverty at the global level, migration across national borders was unavoidable.

He believed that the rapid speed of population growth in the archipelago gave Japan the natural right to overseas migration. Japan, he argued, was just like overcrowded Europe, where people were competing with each other unhealthily for limited space and opportunities and many had to struggle against poverty. Thus, the same as European countries, Japan had to export its surplus people overseas in order to maintain the domestic prosperity. In Sugi’s mind, the United States was the ideal destination for Japanese emigration because it not only was an advanced nation that would lift the Meiji migrants up in the progress of civilization but also had vast unoccupied land with abundant space, wealth, and opportunities.Footnote 68

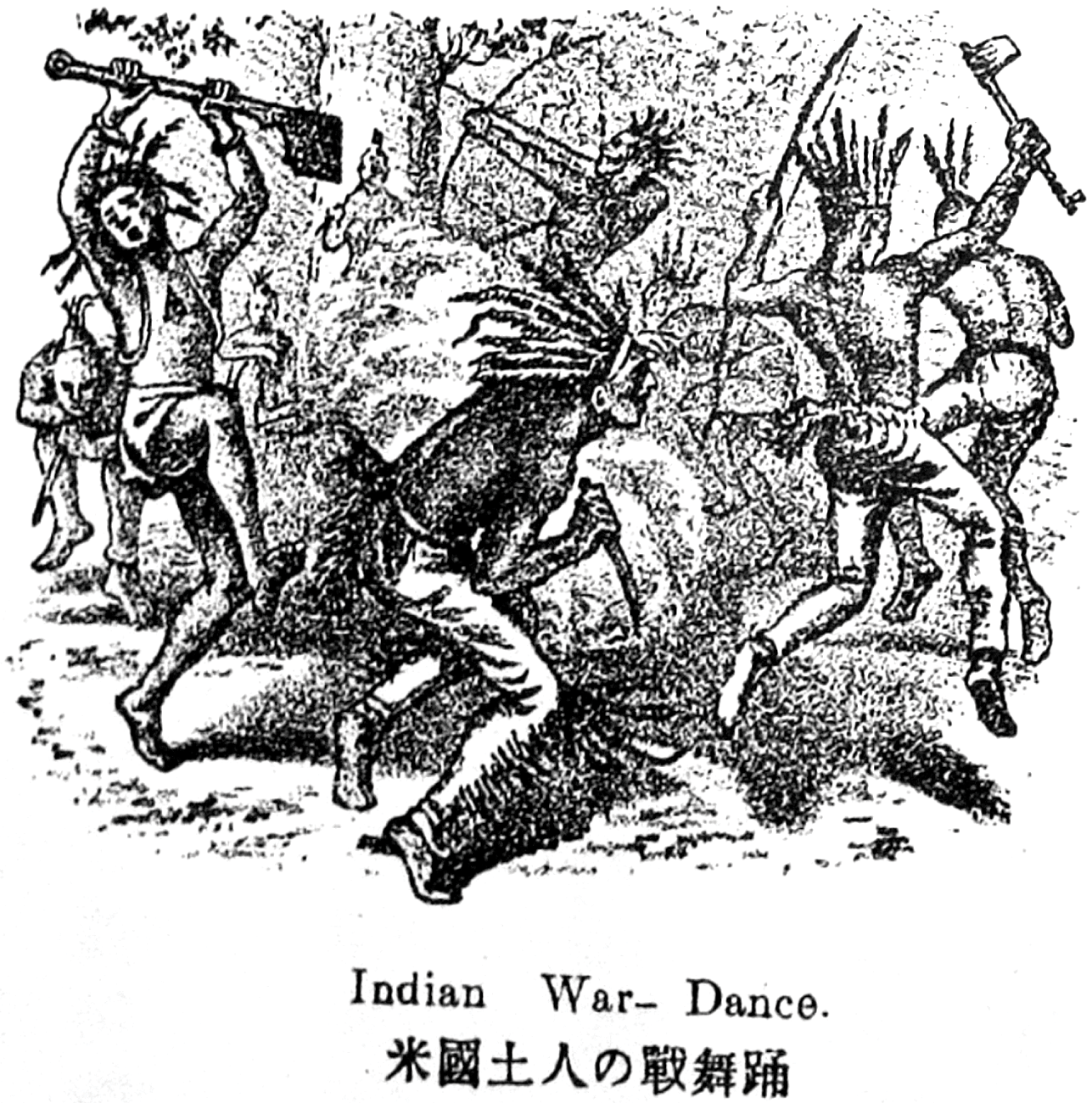

Malthusian expansionism was also embraced by guidebooks for Japanese American emigration in the 1880s. Penned by shizoku travelers and settlers in the United States, these guidebooks described the American West as the heaven for the Japanese, with abundant natural resources and enormous opportunities for both education and work. They encouraged their domestic readers to leave the overcrowded archipelago and follow the example of the Europeans by pursuing their new lives across the ocean. Like the migration to Hokkaido, this route of self-help was also guided by the teleology of Japan’s rise as a civilized empire, with the expectation of transforming emigrants into pioneers of overseas expansion.Footnote 69 Japanese settlers’ colonial encounters with the Ainu in Hokkaido also helped Japanese emigrants to fit themselves into the racial hierarchy in the American West as a dominant race on the same footing as the white settlers. In these guidebooks, Native Americans were called dojin (literally meaning “native people”), the same term used for the Ainu in Japan. A guidebook, Beikoku Ima Fushigi (The United States Is Wonderful Now), drew a further parallel between the Ainu in Hokkaido and the Native Americans in the United States by calling the latter the “Red Ainu” (aka Ezo).Footnote 70 The book described at length the backwardness of the Native Americans, such as their lack of a written language, the primitiveness of their religion, as well as the inequality in gender relations. As Japanese officials and scholars had written of the Ainu, Beikoku Ima Fushigi observed that the Native Americans were quickly vanishing. Amid the wave of civilization, the book observed, they were as vulnerable as “leaves in the autumn wind.”Footnote 71

From 1884 to 1888, quite a few graduates of Fukuzawa’s Keiō School landed in California. In May 1888, the Alumni Association of Keiō School was established in San Francisco with thirty-five members.Footnote 72 In 1885, Fukuzawa initiated a project of collective migration to the United States with the financial support of Hokkaido entrepreneur Yanagida Tōkichi and Keiō graduate Kai Orie, who had opened his own business in California.Footnote 73 Fukuzawa’s promotion of Japanese migration to the United States reached its peak in 1887. In an editorial in the first issue of Jiji Shinpō (Jiji News), an influential newspaper founded by himself, Fukuzawa proposed to establish a “Japanese nation in America” (Nihon koku Amerika no chihō ni sōritsu).Footnote 74 Thanks to the recent opening of the sea route between Tokyo and Vancouver, he rejoiced, people and goods could now easily move across the ocean. As tens of thousands of Japanese subjects began to populate the American West Coast, a Japanese nation (nihon koku) would soon emerge on the other side of the Pacific. He further expected that this newly established Japanese settler nation would become a permanent resource of wealth for the home archipelago.Footnote 75 To realize this goal, he collaborated with Inoue Kakugorō, his student who had migrated to the United States a year earlier. They planned on purchasing land in California in order to build an agricultural colony for Japanese settlers.Footnote 76 Jiji Shinpō also published several articles throughout the year reporting Inoue’s activities in preparation for this plan.Footnote 77 This colonial project was terminated, however, due to the sudden arrest of Inoue during his stay in Japan.Footnote 78

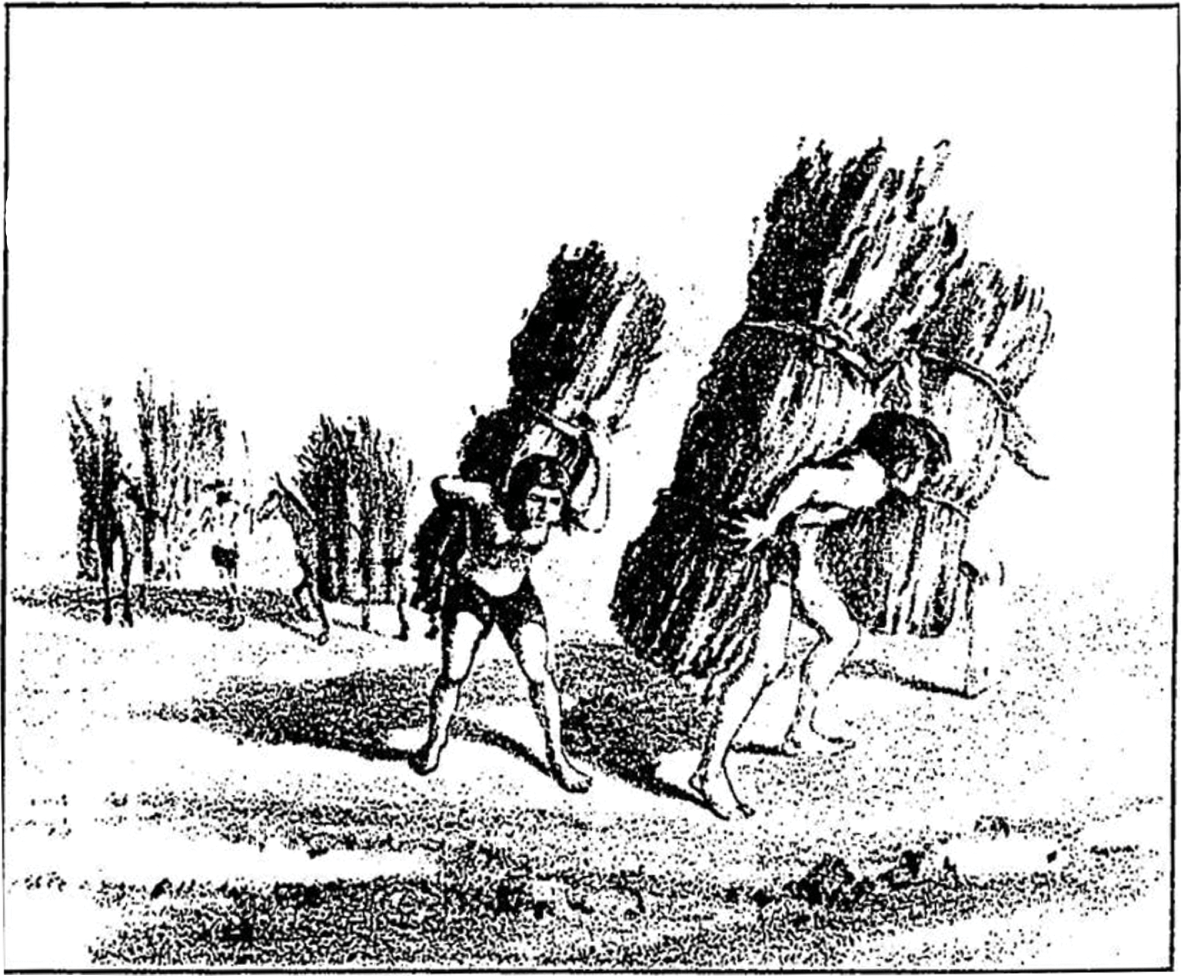

Figure 1.5 This picture appears in a guidebook for Japanese migration to the United States published in Japan in 1886. The Native Americans were not only described as savage but also termed dojin, the same label used for Ainu in Japan.

The failure of Inoue’s colonial project brought Fukuzawa’s promotion of American migration to an end. The early shizoku migrants who made their way to the United States experienced blunt white racism by observing the anti-Chinese campaigns. As Eiichiro Azuma has pointed out, these early Japanese American settlers were well connected with political debates of Japanese elites within and outside of policymaking circles in Tokyo. They read the anti-Chinese campaigns as a strong statement that the American West was reserved for the white European settlers and warned their domestic cohorts that the Japanese would soon be excluded like the Chinese.Footnote 79 Fukuzawa accordingly suspended his promotion for Japanese migration to the United States in 1888.Footnote 80

Women in Malthusian Expansion

The history of shizoku expansion in Hokkaido and North America was not only a story of men but also that of women. If shizoku men were expected to regain their wealth and honor through colonial migration, women of samurai families, on the other hand, were hailed to become mothers of future empire builders. The Meiji government’s attention toward women’s education was initially drawn by the necessity of cultivating settlers of the next generation for Japan’s first colony. One of the earliest governmental initiatives on women’s education in modern Japan was Hokkaido Development Agency’s sponsorship of a group of young women of shizoku families to study in the United States.

When Kuroda Kiyotaka conducted his investigation trip in the United States right before taking the chair of the Hokkaido Development Agency, he was particularly impressed by the influence women wielded in the American society. In a proposal submitted to the imperial government, he reminded Tokyo of the importance of women for the nascent empire. The success of Japan’s colonization of Hokkaido, Kuroda argued, ultimately depended on whether the empire had capable people for this mission. Training of the empire builders should start with little children. It was thus necessary to establish women’s schools to first train the mothers of these empire builders.Footnote 81

In the proposal, Kuroda suggested two specific plans in order to prepare young Japanese women to become mothers in the empire’s first colony.Footnote 82 One was for the Development Agency to establish a women’s school. The other was to sponsor a selected group of young women to study in the West. As a result of Kuroda’s proposal, five girls from shizoku families were chosen to study in the United States along with the Iwakura Mission.Footnote 83 Among these five girls was six-year-old Tsuda Umeko, the second daughter of Tsuda Sen himself. Tsuda Umeko arrived in San Francisco in 1871 and stayed in the United States until her return in 1882. Unsatisfied with the opportunities she had in Japan, she embarked on another study trip in the United States between 1889 and 1892 to receive a college education at Bryn Mawr College in Philadelphia. Through her successful efforts in fund-raising, Tsuda Umeko managed to establish a scholarship in 1893 to support other Japanese women to study in the United States.Footnote 84 Seven years later, she funded the Women’s Institute for English Studies (Joshi Eigaku Juku), later known as Tsuda College, in Tokyo.Footnote 85

Nakamura Masanao, a central advocate of shizoku resettlement and supporter of Hokkaido expansion, was also among the earliest Japanese modern thinkers to emphasize the importance of women’s education. In an 1875 article, titled “On Creating Good Mothers,” he argued that producing and cultivating qualified children were crucial for Japan to become a civilized nation and empire like the Western powers. All women in Japan thus should receive education in order to become competent mothers who could take on the mission to nurture the next generation of nation and empire builders.Footnote 86

Fukuzawa Yukichi, another supporter of Hokkaido and American migration, was a passionate speaker for women’s freedom and rights. Motherhood was the core in his reasoning. In response to the challenge of the West, Fukuzawa believed that the Japanese racial stock should be physically improved according to that of the Westerners. The first step, he argued, was to change the social condition of women. Under the backward custom of Tokugawa society, women lacked responsibility and joy in their daily life. For this reason, they were physically weak, as were the children they gave birth to. As a result of the social suppression of women over the past few hundred years, the physical body of average Japanese was weak and small. The nation would not have strong and healthy offspring unless Japanese women’s mental and physical conditions were improved.Footnote 87

Fukuzawa also observed that the freedom and rights of women should be understood in the context of Western imperial expansion and the global hierarchy it created. Women’s position in a society, as he saw it, symbolized the degree of progress in civilization achieved by the nation. Fukuzawa called for more opportunities for women in education and employment and equal social rights like men in marriage and property ownership.Footnote 88 For him, women’s position not only offered a barometer to gauge Japan’s achievement in Westernization but also enabled Japan to establish its own imperial hierarchy with its Asian neighbors. Although Japan fell behind Western powers in the improvement of women’s condition, Fukuzawa contended, Japanese women enjoyed much more freedom and joy than their counterparts in Joseon Korea and Qing China.Footnote 89 His famous essay “On De-Asianization,” written in 1885, the same year when he celebrated the social condition of Japanese women as better than that of Chinese and Korean women, used the same logic to urge the nascent empire to embrace Western civilization on the one hand and to launch its own colonial expansion in East Asia on the other hand.Footnote 90

In addition to the good women who would serve the empire as mothers, Fukuzawa also recognized that bad women were equally valuable. He argued that prostitution contributed to the society by providing an indispensable outlet for the energy of men who failed to marry due to poverty. Otherwise, these men might threaten social stability.Footnote 91 Ever the pragmatist, he found reasons to celebrate the emigration of a growing number of Japanese prostitutes around the Pacific Rim that began in the late nineteenth century.Footnote 92 While the shizoku men should take leadership in overseas Japanese communities,Footnote 93 the Japanese prostitutes abroad were a “necessary evil” (hitsuyō aku) for the empire in two ways: they would facilitate migration-driven expansion by satisfying the sexual needs of Japanese male emigrants,Footnote 94 and their remittances back to the archipelago would be a boon to Japan’s nascent capitalist economy, which was still at the stage of primitive accumulation.Footnote 95

Conclusion

Malthusian expansionism, stressing the need to find extra land to accommodate the rapidly growing domestic population, was initially invented during British colonial expansion in North America in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. It legitimized the British transatlantic expansion by simultaneously warning against the dangers of overpopulation and celebrating the overall demographic growth of the British Empire. This chapter has demonstrated how Malthusian expansionism was transplanted to Japan in early Meiji. It was the Meiji empire’s imitation of Anglo-American settler colonialism in its own colonial migration in Hokkaido that allowed Malthusian expansionism to take root in Japanese soil.

Such imitation, as demonstrated by the first wave of Japanese migration to the United States, spearheaded by Fukuzawa Yukichi, allowed Japanese expansionists to turn to North America as an ideal destination for Japanese migration in the mid-1880s. Shizoku expansionists later also cast their gaze on other parts of the Pacific Rim with the same mind-set.Footnote 96 After Japan acquired Taiwan as a colony from the Qing, Fukuzawa immediately called for mass migration from the overcrowded archipelago to Taiwan in order to explore the latter’s natural wealth (fugen wo kaihatsu suru). To live out the true meaning of civilization (bunmei no hon’i), he suggested, the Japanese should follow the model of Anglo-American expansion by monopolizing the entire island and all its products as well as banishing the benighted aborigines from their own land.Footnote 97

Tsuda Sen and his extended family also provide a telling example. After serving as the editor of the Hokkaido Kaitaku Zasshi, Tsuda Sen turned his colonial gaze toward Korea and later Northern China, while his son Tsuda Jirō migrated to California to foster Japanese American agricultural settlements.Footnote 98 Tsuda Umeko, one of the first women of modern Japan to receive an education in the West, remained single and childless her entire life. In this sense, she failed to fulfill her obligation to the empire as a mother of Hokkaido colonists, the original expectation of Kuroda Kiyotaka to support her first study trip in the United States. However, as one of the earliest promoters of women’s education in modern Japan, her lifelong career demonstrated the close connections between women’s education and Japan’s migration-based expansion from the very beginning. Among the awardees of the scholarship she established for Japanese women to study in the United States was Kawai Michi.Footnote 99 Kawai became an influential leader of the Japanese Young Women Christian Association and a central figure in the women’s education movement who spearheaded the campaign to educate Japanese female migrants on the American West Coast. Tsuda Umeko’s elder sister, Tsuda Yunako (later Abiko Yunako), was a direct beneficiary of the Women’s Institute for English Studies. Growing up in Hakodate, Hokkaido, Tsuda Yunako both studied and then taught at the institute. She later migrated to San Francisco after marrying a Japanese American, Abiko Kyūtarō. Abiko Yunako founded the Japanese Young Women Christian Association in San Francisco in 1912 and served as its director until 1923. The primary goal of the association was to familiarize Japanese female migrants with American customs and child-rearing skills in order to facilitate Japanese community building in the United States.Footnote 100 Abiko Kyūtarō, husband of Abiko Yunako, was the editor of Nichibei Shinbun (Japanese American News), a leading San Francisco–based Japanese American newspaper. He was not only a community leader for Japanese Americans in California but also a trailblazer in Japanese land acquisition in Mexico.Footnote 101

In a more general sense, Japan’s colonization of Hokkaido in early Meiji established the intellectual foundation for Japanese colonial expansion and overseas migration in the following decades. Numerous late nineteenth-century participants in the Hokkaido colonial project as well as people who were directly influenced by them later became the arms and brains of Japanese expansion abroad. Satō Shōsuke and Nitobe Inazō, students at Sapporo Agricultural College (the predecessor of Hokkaido Imperial University), later taught classes on history and the policies of colonialism at the same college. They trained a group of scholars who would later sway public opinion and state policies on overseas expansion.Footnote 102 Shiga Shigetaka, Fukumoto Nichinan, and Kuga Katsunan, participants in the colonization of Hokkaido in early Meiji, grew into key members of the Association of Politics and Education (Seikyō Sha).Footnote 103 The association became the cradle of Japanism (kokusuishugi) and other ideologies in favor of Japanese expansion into Hawaiʻi, the South Pacific, and Latin America. Other influential advocates for the Hokkaido expansion, such as Taguchi Ukichi and Wakayama Norikazu, held different ideas from Seikyō Sha members and also disagreed with each other. However, they also quickly looked to the South Pacific and Latin America as migration destinations. Sakiyama Hisae, a colonial settler in Hokkaido in the 1890s, established the School of Overseas Colonial Migration (Kaigai Shokumin Gakkō) in 1916, training Japanese youth and facilitating their migration to South America.Footnote 104 The next chapter elaborates on how the gaze of Meiji Malthusian expansionists shifted quickly from the North to the South and how the experience of colonial expansion in Hokkaido and Japanese migration to the United States in the 1880s paved the way for this transition.

Fukuzawa Yukichi urged his fellow countrymen who migrated to the United States to follow the model of Anglo-American expansion – they needed to commit themselves to long-term settlement in order to have permanent achievement abroad.Footnote 1 The majority of the migrants during the last two decades of the nineteenth century, however, did not subscribe to this notion. With strong ambitions back home, the majority of Fukuzawa’s students who made their way across the Pacific at that time had no intention to live out the rest of their lives in California. Some began to return to Asia in the late 1880s.Footnote 2

The ease of migrant movement between Japan and California at the time was strengthened by another wave of Japanese migration to the United States, triggered by the Meiji government’s suppression of the Freedom and People’s Rights Movement. Initiated by the Tosa clan under the leadership of Itagaki Taisuke, this sociopolitical movement attracted many shizoku and rural elites from all over the country. It demanded the freedom of speech, the freedom of association, and the creation of a parliament in order to increase political representation for the common people. The Meiji government responded to this movement negatively. It promulgated the Public Peace Preservation Law in 1887, allowing itself to expel from the capital individuals considered detrimental to political stability and to imprison those who did not comply with this verdict of exile.Footnote 3 Thus chased out from the political center of the empire, some members of the movement chose to migrate to the United States, the nation they thought of as the true embodiment of freedom, to continue their political campaign. Using San Francisco as their base, these exiles formed the Federation of Patriots (Aikoku Yūshi Dōmei) in January 1888. They continued to criticize the political establishment in Japan by publishing periodicals in Japanese and sending copies of each issue back to Tokyo. To circumvent state censorship, they had to constantly change the names of their publications. In 1888 alone, the Meiji government banned the sale of more than twenty-one different newspapers shipped from San Francisco – a testament to the overlapping intellectual spheres in Tokyo and San Francisco.Footnote 4

A boom in the publication of trans-Pacific migration guides and writings of Japanese travelers in the United States beginning in the late 1880s further connected the minds of Japanese expansionists on both sides of the Pacific Ocean. Most of these migration guides were authored by migrants themselves, aimed at encouraging Japanese audiences to prove themselves by earning wealth and honor in the Golden State. Travelers such as Nagasawa Betten and Ozaki Yukio also provided their domestic readers with a significant amount of information about the United States in general and its Japanese immigrant communities in particular. Their writings included messages they collected from Japanese Americans as well as their own observations. In summary, before the 1980s rise of migration companies that would play a critical role in the mass migration of laborers from the archipelago to the West Coast of the United States, Japanese communities in mainland America tended to be small in size, mainly composed of self-financed students and political exiles. Even though they were now physically located in San Francisco instead of Tokyo, these settlers were well connected with thinkers and politicians back in Japan.Footnote 5

Meanwhile, the experience of the Chinese migrants who had reached the shores of North America decades before the Japanese had also shaped the minds of Japanese expansionists in Tokyo and San Francisco. On one hand, the Japanese intellectuals and policymakers saw American exclusion of Chinese immigrants as an ominous warning to get ready for the destined battle between the white and yellow races; on the other hand, they looked at the existence of numerous Chinese diasporic communities all around the Pacific Rim as both a potential threat and a possible model.Footnote 6

It was within this context of trans-Pacific dialogue between the shizoku expansionists and political dissidents that the discourse of southward expansion (nanshin), a major school of expansionist thought throughout the history of the Japanese empire, first emerged.Footnote 7 As the following pages demonstrate, if white racism forced Japanese expansionists to explore alternative migration destinations, Malthusian expansionism continued to legitimize Japanese migration-driven expansion. Both factors contributed to the construction of the nanshin discourse. The campaigns of shizoku expansion to Hokkaido and the United States together laid the ground for the initial phase of Japan’s expansion to the South Seas and Latin America.

As it was with all schools of expansion within the Japanese empire, southward expansion – both as an ideology and as a movement – was a complicated construct from its very inception. Starting in the late 1880s, different interest groups proposed a variety of agendas for expansion, their primary aims ranging from commercial to naval and agricultural. The ideal candidates for migration in these blueprints also ranged from merchants, laborers, and farmers to outcasts known as the burakumin.Footnote 8 However, the domestic struggles of shizoku settlement continued to serve as the dominant political context in which the nanshin discourse was originally proposed and debated. Like it was for the preceding Hokkaido and American migration campaigns, shizoku were initially regarded as the most desirable candidates for southward expansion.

Existing literature tends to define nanshin, literally meaning “moving into the South,” as a school of thought that promoted Japanese maritime expansion southward in the Pacific including the South Pacific and Southeast Asia.Footnote 9 This geography-bound understanding is mainly derived from the definition of Nan’yō as a geographical term in Japanese history. Literally translated as “the South Seas,” Nan’yō had different meanings in different contexts. But it has been generally considered that in its widest scope, Nan’yō covers the land and sea in the South Pacific and Southeast Asia, the two geographical regions that the works on Japanese southward expansion by Mark Peattie and Yano Tōru have focused on respectively.Footnote 10 However, as this chapter explains, for Japanese expansionists in the late nineteenth century the South Seas also included Hawaiʻi.Footnote 11 In addition to Hawaiʻi, other nanshin advocates in history did not confine their sights within the South Seas. Some also included Latin America in their blueprints of southward expansion.Footnote 12

Currently the history of Japan’s southward expansion is being studied as a subject within the nation-/region-based narrative of the Japanese empire, one that excludes the experience of Japanese migration to Latin America and Hawaiʻi.Footnote 13 However, as this chapter illustrates, the calls for expansion into Latin America and Hawaiʻi were proposed in conjunction with calls for expansion into the South Seas. The nanshin advocates envisioned that Japanese expansion to areas located geographically south to the Japanese archipelago and Japanese communities in the United States would be able to circumvent Anglo-American colonial hegemony. Following the experiences of shizoku expansion to Hokkaido in the 1870s and 1880s and to North America in the 1880s and 1890s, the campaigns for expansion to the South Seas and Latin America belonged to the same wave of shizoku expansion that was firmly buttressed by Malthusian expansionism.

Reunderstanding the World in Racial Terms

Experiences in the United States promoted shizoku migrants and visitors to adopt a race-centric worldview. Replicating the racial thinking of many expansionists in the West,Footnote 14 the Japanese expansionists’ definition of race was directly derived from Charles Darwin’s theory of natural selection. They were convinced that the world of mankind, like that of nature, not only was composed of biologically different human races but also followed the principle of survival of the fittest. The contemporary competition among nations, they believed, was a reflection of the biological struggle for the limited space and resources among the races. Their perception of the world as an arena for racial competition converged with the intellectuals in domestic Japan on whether the nation should endorse mixed residence in inland Japan (naichi zakkyo) in order to revise the unequal treaties. This would allow Westerners (as well as Chinese and Koreans) to travel, settle in, and conduct business throughout the Japanese archipelago without restriction. A group of hard-liners, later known as promoters of national essence (kokusuishugisha), warned that the white races were taking over the world by not only excluding the yellow races from the West but also invading their homelands in the East. They formed the Association of Politics and Education (Seikyō Sha) in 1888, organizing public lectures as well as publishing journals and newspapers, urging their countrymen to assume a position of leadership in the inevitable worldwide racial competition. To avoid racial extinction, they argued, the Japanese needed to compete with the white races as the leader of the yellow races; in order to emerge victorious from this competition, they must reaffirm their cultural roots and launch their own colonial expansion.

The Japanese American experience’s influence on the growing discourse of racial competition in Tokyo was particularly evident in the writings of Seikyō Sha thinker Nagasawa Betten. Nagasawa went to the United States to study at Stanford University in 1891, and there he joined the Expedition Society (Ensei Sha),Footnote 15 a political organization formed by exiled Freedom and People’s Rights Movement activists in San Francisco, and participated in their debates about the future of Japanese expansion.

Drawing from his own experience in the American West, Nagasawa wrote to his intellectual friend and fellow Seikyō Sha member Shiga Shigetaka about the importance of adopting a race-centric worldview:

While the competition between nations is evident, the competition between races remains invisible. People take the visible competition seriously and prepare themselves for it, but only experts can sense the invisible competition and thus few efforts are made for its preparation. The crucial point lies not in the former but the latter. … Living among people of other races, my sense of urgency about the need for making preparations for racial competition grows each day. The urgent task now, as you have proposed, is to promote our national essence and to inspire our countrymen’s spirit of overseas expansion.Footnote 16

Nagasawa thus shifted the primary subjects of global competition in expansion from nation to race, the power of which was not bound by national territory. This view allowed him to place overseas migration at the center of Japanese expansion. He concluded, “Overseas expansion is the most effective way to prepare for racial competition. … Once our fellow Japanese find their footing in every corner of the world, it will doubtlessly lead to our triumph in the racial competition.”Footnote 17 In his book The Yankees (Yankii), published in Tokyo in 1893, Nagasawa Betten embraced American frontier expansionism and described the national history of the United States as a living example of it.Footnote 18 The Mayflower ancestors of the American people, he wrote, overcame many hardships to establish the first thirteen colonies as the foundation of their nation, and their expansion had not ceased ever since. The American borders had extended beyond the Mississippi River and the Rocky Mountains, reaching the coast of the Pacific Ocean. If the railway bridging the two Americas were completed, the United States would become a natural leader of the entire Western Hemisphere due to the wisdom and wealth of its people.Footnote 19 While Nagasawa did not believe that Japanese overseas expansion was triggered by religious and political persecutions, he argued that the Japanese should nevertheless emulate the Mayflower settlers’ frontier expansionism in order to establish a new, large, prosperous, and mighty nation much like the United States.Footnote 20

However, in this trans-Pacific reconstruction of Japanese expansionism, Anglo-American settler colonialism was not the only reference for the Japanese intellectuals. The omnipresent influence of Chinese Americans on their lives in San Francisco led the Japanese expansionists to include the Chinese expansion model as another point of reference. The existing literature on Japanese American history has well documented the fact that the Japanese immigrants replicated white racism toward their Chinese neighbors in the American West. To combat white racism, they strove to prove their own whiteness and spared no efforts to separate themselves from the “uncivilized” Chinese laborers.Footnote 21

This attitude, however, constituted only one aspect of the Japanese migrants’ complicated feelings about their Chinese counterparts in the late nineteenth century. Arriving in the American West decades earlier than the Japanese, the Chinese immigrants founded the earliest Asian communities that the first Japanese immigrants readily resided in.Footnote 22 While shizoku setters felt insulted when they were mistaken for Chinese, they also admired Chinese achievements in the land of white men. Mutō Sanji, a Japanese business tycoon who sojourned in the United States during the Meiji era, published a guide for Japanese migration to the United States in 1888. In this book, he argued that in the destined global competition between the white and the yellow races, the Chinese had offered a good example for the Japanese on how to compete with the white races.Footnote 23