But to be serious, upon what seems to me the most serious things in human life, the character a Man enjoys and the example he transmitts. I look upon the toleration, and indeed encouragement given to Calumny to be one of the worst symptoms of the declining virtue of the age. When I was young (it is a great while ago) character was considerd as a serious thing; to attack it was thought the greatest outrage of an enemy; to receive any damage in it, the greatest of injuries, and the worst of misfortunes. Now no one seems interested for his own character or for that of his Friend, & indeed the daily libel has levelled all distinctions. But for want of Attick salt the Libel of Monday, is become too stale for Tuesdays use, & these Calumniators, like the flesh fly, live but a day, & they have only tainted what they have prey’d upon. Indeed if it shall become a fashion for Men of Witt and of distinguish’d situations, to leave behind them malicious libels on their Cotemporaries, this new species of mischief will be more serious and important.

As I hinted in the conclusion of Chapter 2, the 1770s might be seen as a turning point in the coterie life of Elizabeth Montagu and her closest associates, now widely known for their assemblies in Vesey’s and Montagu’s London houses. With the deaths of the Earl of Bath in 1764 and of George, Lord Lyttelton in 1773, the Montagu‒Lyttelton coterie (of which Vesey had become a central member in the 1760s as well) shifted from a mixed-gender core group to a more feminocentric one. In Bath, Montagu lost above all an intimate friend; in Lyttelton, Montagu suggests to Vesey, she lost someone who had been essential to the construction of her identity and cultural place:

He was my Instructor & my friend, the Guide of my studies, ye corrector of ye result of them. I judged of What I read, & of what I wrote by his opinions. I was always ye wiser & the better for every hour of his conversation. He made my house a school of virtue to young people, & a place of delight to the learned. I provided the dinner, but his conversation made ye feast. If any young man of genius appeared he encouraged him, praised him, produced him with advantage to the World. I have lost my consequence in Society with him, but you my dear friend will love me still.2

Lyttelton’s death evokes a strikingly elegiac tone in relation to the coterie itself; almost a year later, Vesey speaks of it in similar terms, as a thing of the past – “you & I my Dear friend were acquainted with the great Lights of the last Age they are all now (I think) extinct” – to which Montagu replies, “You are more than necessary to me, you are all I have left of our incomparable, our excellent Lord Lyttelton. In you I retrieve a thousand graces that distinguish Lord Bath, Your mind gives me back their image, not one feature of their character was lost with you.”3

Montagu’s formulation, which makes Vesey the ideal receptacle, interpreter, and mirror of the characters of Lyttelton and Bath, anticipates the sharp tensions around the notion of character that would arise almost ten years later with the publication of Samuel Johnson’s 1781 “Life of Lyttelton.” This chapter will begin by looking at the detached and commodified public representations of Montagu and her circle that circulated in the aftermath of the coterie period that ended with the death of Lyttelton. While often laudatory, I will show how these representations can be related to a broader pattern of attacks on the coterie model of literary production – particularly on the coterie’s control of circulation and its claim to guarantee the truth and quality of its members’ productions. Before discussing the most notorious attacks, those of Samuel Johnson in his Lives of the Poets, I will suggest further background to this quarrel in the evolving relationship between Montagu and Johnson through the 1760s and 1770s, and in the shared response of Montagu and Philip Yorke, now the second Earl of Hardwicke, to the posthumous publication of the Earl of Chesterfield’s manuscript character sketches. Sören Hammerschmidt has claimed that “wherever character was discussed and analyzed” in the eighteenth century, “it arose within the interstices between the media forms that gave it legibility and currency. In other words, the formulation of character always occurred in the contact zones where opinions and arguments in their mediated forms (oral or written, visual or textual, manuscript or print) encountered each other.”4 This chapter’s argument will show that it was indeed around the idea of character – its preservation, formulation, transmission, and use – that the differences between media regimes could become sharply apparent. From this perspective, I will reconsider the disagreement between Johnson on the one hand and Montagu, Hardwicke, Richard Graves, and their allies on the other as about something much more than what Boswell reports as the “feeble, though shrill outcry” of “prejudice and resentment.”5

Montagu and her friends after the coterie

An onlooker might have been forgiven for dismissing Montagu’s and Vesey’s 1773–74 laments for the end of their ascendancy as mere effusions of grief. If anything, Montagu’s cultural power continued to expand its reach. For example, in the summer punctuated by Lyttelton’s death, her determined quest to obtain a government pension for the Scottish poet and philosopher James Beattie finally reached fruition. From about 1770, when Montagu received word from Scotland of Beattie’s published attack, in his Essay on the Nature and Immutability of Truth, in Opposition to Sophistry and Skepticism, on David Hume’s skeptical philosophy, Montagu had stimulated and coordinated the efforts of bishops, government ministers, and university dons to serve the relatively unknown Scot. She secured the publication of his poem The Minstrel (book one was published in 1771) and the awarding of a pension from the King and a doctorate of laws from Oxford in 1773.6 In the “Advertisement” to his 1776 Essays, a financial success for which Montagu had diligently recruited subscribers, Beattie describes the project in terms that celebrate his patron’s cultural power almost as much as his own favor with the elite. He notes that his “Friends” promised him to conduct the entire project outside of the world of commercial exchange, without recourse to booksellers, advertisements, or solicitation; rather, they have succeeded by simply inviting subscriptions from the “many persons of worth and fortune, who wish for such an opportunity, as this will afford them, to testify their approbation of [him] and [his] writings.”7

Montagu’s cultural ascendancy was sustained by a secure social and economic position as through her husband Edward she became the ever-wealthier owner of vast land estates and coalmines in the north of England. Before Edward Montagu’s death in 1775, she was already very involved in the management that enhanced the value of the couple’s properties, though she had only limited ability to embark on major expenditures; as a widow, she had sole control of significant possessions and annual income. Elizabeth Eger has argued that Montagu’s material manifestation of her wealth, particularly through her houses in Hill Street – where she created a chinoiserie dressing room in the early 1750s and engaged the leading architects James Stuart and Robert Adam for a major redecoration of the reception areas in the 1760s – and then in Portman Square, the mansion she built after the death of her husband, embodied “virtuous magnificence” as “monuments to [the ephemeral culture of] bluestocking philosophy.”8 Her contemporaries commented frequently on the striking displays of grandeur, the patronage of every branch of the arts, and the gathering of leading talents of Britain and the Continent which combined to create the brilliance of Montagu’s assemblies. With the move to Portman Square in 1781, these assemblies took on a distinctly larger, more formal, and somewhat impersonal scale: they became even more public, and publicly remarked, than before.

Reflecting this role of cultural leadership, Montagu, Carter, and Vesey – the women of the now-dissolved coterie – were experiencing a flowering of public recognition and adulation in the 1770s. In 1770, for example, “a Lady” submitted to The Gentleman’s Magazine “A Plan for an unexceptionable Female Coterie” that would be presided over by Montagu, with the assistance of Carter and Chapone. In 1773, Montagu reports to Carter that

a Writer in one of ye Magazines, says ye honour of a Doctors Degree had been more properly conferred on Mrs Eliz Carter & Mrs Montagu, than on a Parcel of Lords, Knights, & Squires, who are unletterd, to Mrs Macaulay Miss Aikin & some others he would bestow a Master of Arts of degree. I ought to have been ashamed to have been named in a day with Mrs Carter, but I will confess, I am always delighted with this enourmous flattery. I hope my pleasure does not entirely arise from vanity, but partly from tenderness, which feels inexpressible satisfaction in whatever seems to unite us.

And in 1774, Mary Scott’s The Female Advocate: A Poem celebrates Montagu’s “Genius, Learning, … [and] Worth,” not merely for her critical essay on Shakespeare, but for her “nobler Fame” of being “Still prone to soften at another’s woe,/Still fond to bless, still ready to bestow.”9

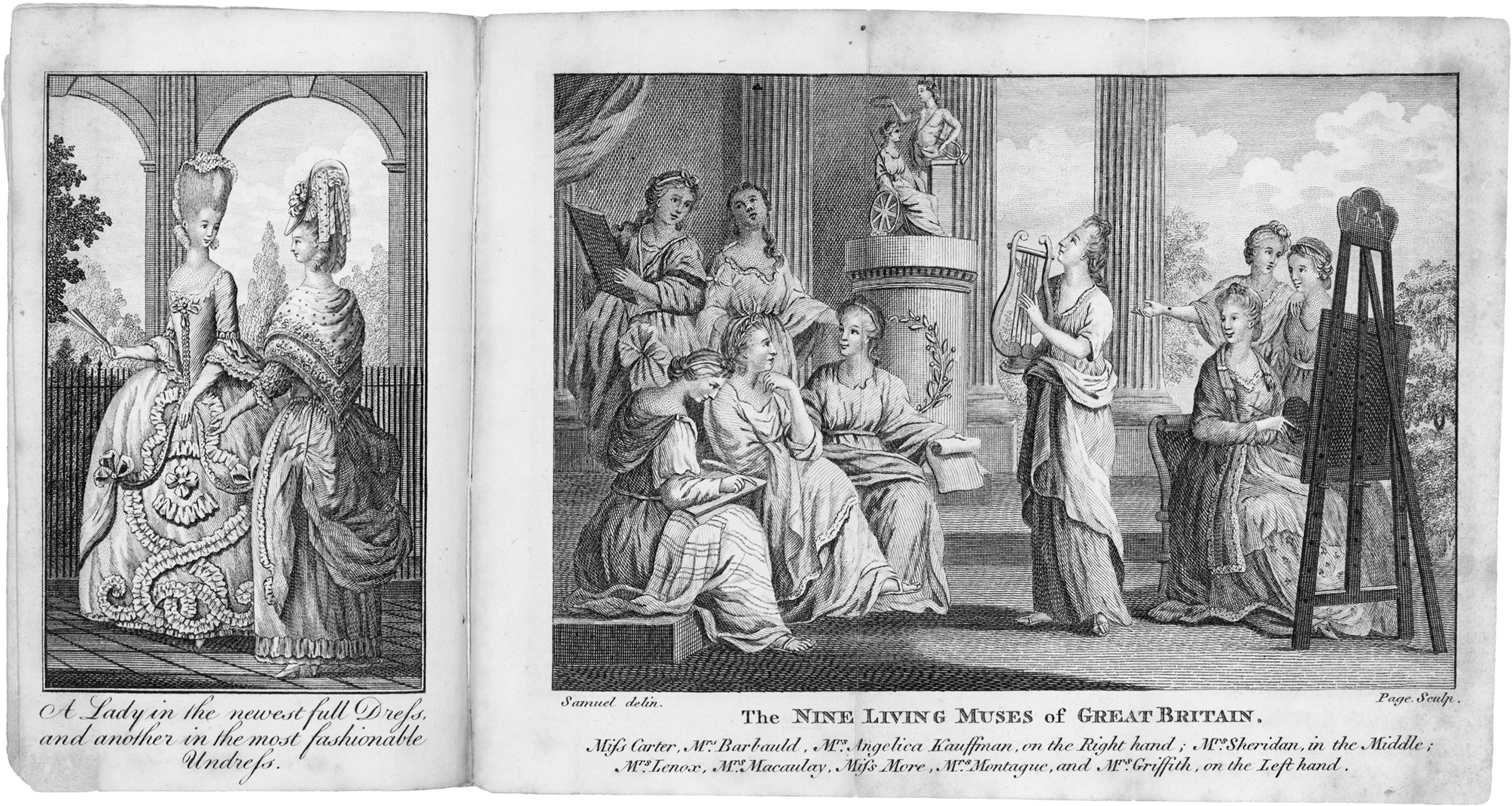

There is, nevertheless, an important distinction to be drawn between the group-building and mutual encouragement functions of the poetry produced by the intimate coterie – poems like Carter’s “To Mrs. [Montagu]” and Lyttelton’s “The Vision” discussed in Chapter 2 – and the manifestations of celebrity represented by the “Plan for an unexceptionable Female Coterie” or the imaginary conferral of doctorates. The contrast can be illustrated with a comparison between a publication of the early 1770s – the poem “To the Naiad of Tunbridge Well” – and the Ladies New and Polite Pocket-Memorandum Book for 1778, published by Joseph Johnson, with its frontispiece engraving of the “Nine Living Muses of Great Britain” (Figure 5.1). “To the Naiad,” published in the St. James’s Chronicle dated June 26, 1771, and signed R.M., expresses the hope that Montagu, “justly celebrated for her most ingenious and manly Essay on the Genius and Writings of Shakespear,” will find her health re-established by her stay at the resort. It presents itself as an extension of more select modes of sociability, offering the public a glimpse of the coterie and launching a flurry of speculation among its members about who among their close acquaintances might be its author (Stillingfleet and Garrick are suggested). Even The Female Advocate, although its author seems to have been unknown to the women she celebrates, maintains the holistic, “embodied” approach of the coterie, presenting the accomplishments of female authors as a sign of a complete, knowable, and admirable character, if only that of a conventionally feminine ideal. The often-discussed engraving of the “Nine Living Muses,” on the other hand, makes no attempt to create a sense of intimate access to an embodied group. That the features of Montagu, Carter, and the other figures were indistinguishable even to the engraving’s subjects (see below) reflects the fact that Richard Samuel, painter of the original behind the engraving, was unknown to them and did not paint from the life. Moreover, the women represented moved in very different circles from one another and in several cases were not mutually well-disposed.

Figure 5.1 Fashion plate and foldout plate of The Nine Living Muses of Great Britain, after Richard Samuel, in The Ladies New and Polite Pocket Memorandum-Book for 1778.

It is tempting to posit a link between this shift from coterie-centered to print-generated fame and concurrent developments in the print trade. The year 1774 saw the landmark Donaldson v. Becket decision definitively abolishing perpetual copyright and opening up the print market to reprint publication. And just after the time when Beattie’s “Advertisement” to his Essays was describing his subscription publication as the product of word of mouth and pen, neither “committed to booksellers, nor made public by advertisements,” there appeared the first volumes of John Bell’s Poets of Great Britain, followed closely by the rival Works of the English Poets for which Johnson wrote his biographical and critical prefaces of 1779–81, events Margaret Ezell has described as definitively establishing “all the mechanisms for the presentation of bulk literature to a consuming public.” Such highly commercialized publications promised writing that had been authorized by the best judges; they offered entertainment and utility, and thereby participation in national literary culture, to a broadly inclusive audience. There is no denying that the decade also saw an upswing in sheer numbers of print publications, as Michael Suarez has shown in his bibliometric overview of publishing patterns for the century: even though Suarez’s category of “literature, classics and belles-lettres” retains a stable share of total published titles over the century, that stable share represents a net increase.10

My study does not claim, however, that the literary coterie was a significant cultural force by virtue of numerical dominance of literary production. Rather, representation and perception were the wellsprings of its influence. From this perspective, for the coterie centered on Montagu, the 1770s and 1780s could be described as a new period of conflict as the balance of representation shifted: in consigning its fame to the medium of print, the coterie gained broader exposure but lost control over its image. To put it in terms of the “Nine Living Muses” in the Ladies New and Polite Pocket-Memorandum Book, on the one hand, as Montagu writes, “it is charming to think how our praises will ride about the World in every bodies pocket. Unless we could all be put into a popular ballad, set to a favourite old English tune, I do not see how we could become more universally celebrated”; on the other, as Carter replies, “to say truth, by the mere testimony of my own eyes, I cannot very exactly tell which is you, and which is I, and which is any body else.” In Eger’s formulation, consumers were being offered not a handful of individualized characters but an icon, a public representation of feminine achievement that “illustrated the power of Britain as Europe’s most highly cultured, proto-imperial power” – a representation to which they could show their allegiance by purchasing a pocket memorandum book.11

Paradoxically, both Carter and Montagu seem to have with some self-consciousness ceded control of their public images, at the moment of their greatest influence, by repudiating literary production and publication and increasingly identifying themselves with their patronal and charitable achievements. Guest has examined in detail Carter’s “retirement from publishing, and from social visibility, in the mid-1770s”;12 similarly, Montagu articulates to Carter her decision to cease authorship despite all conditions being favorable to further publication:

My health continues admirably good & my eyes are getting better & if I could hope on any subject to say what had not been said before or to say it better I should feel great impatience to set about some work, but beyond my private amusement I have little motive to any undertaking. I often think the World will grow wiser in regard to the affair of Reading, & that such as do read will confine themselves to a few original authors, & not continue to trifle away their lives over the frivolités of their Cotemporaries … At present I think my great delight is making rice milk, & rice puddings, & cheap broth. The poor in this Neighberhood [sic] are in a state of wretchedness not to be described.13

While this decision can be attributed to the personal factors already cited – the death of Lyttelton, Montagu’s increased responsibilities as landowner and coal magnate leading up to and after the death of her husband, her own advancing age (she turned sixty in 1778), and her embarking on the role of hostess on an enlarged scale in Portman Square – it had implications for representations of the cultural significance of her circle, which began at times to display the conventions of anti-aristocratic and misogynist satire. An icon, after all, is an exchangeable symbol, which can be commodified and deployed far beyond the original’s control: in this case, as an ideal of feminized patriotism and refined sociability, or as a derogatory cliché of lascivious tête-à-têtes or silly and quarrelsome pretentiousness.

As a backdrop to specific representations of Montagu’s circle, a series of late 1770s attacks on manuscript exchange as a social phenomenon suggests that at least some print authors felt threatened by its continued cultural power. Often these attacks reflect coterie publication’s relatively recent role as a form of satirical opposition discourse by associating it with the circulation of scandal manuscripts. In Frances Brooke’s 1777 novel The Excursion, for example, the representative target is a female writer of scandal, Lady Blast, but the critique is not a specifically gendered one – rather, the narrative portrays the power wielded by what it calls “a certain set” of wealthy, urbanized aristocrats, through the promiscuous circulation and publication in scandal magazines of authorless manuscript narratives designed to destroy the social reputations of unsuspecting individuals. The narrator seeks to persuade the consumers of print to boycott such publications: “It is in your power alone to restrain the growing evil, to turn the envenomed dart from the worthy breast. Cease to read, and the evil dies of itself: cease to purchase, and the venal calumniator will drop his useless pen.” The very urgency of the address affirms the extent to which the periodical press has allowed itself to depend on such copy and readers have become addicted to the voyeuristic thrill of glimpsing manuscript material supposedly meant for restricted circulation. A similar representation is that of the scandal club created by Richard Sheridan in his 1778 comedy The School for Scandal, whose “circulate[d] … Report[s],” especially when they reach the published papers, are the boasted cause of multiple broken matches, disinherited sons, “forced Elopements,” “close confinements,” “separate maintenances,” and divorces. Within the confines of the play, the club is ultimately exposed and rendered impotent, but the persistent power of coterie scandal writing is affirmed by a framing prologue that mocks the “Young Bard” who “think[s] that He/Can Stop the full Spring-tide of Calumny.”14

Immediately following Brooke’s and Sheridan’s works, Frances Burney composed a sharp satire of a literary coterie in her play The Witlings, written and then suppressed in 1779. In The Witlings, a coterie circle called the “Esprit Club,” whose leader Lady Smatter in several respects resembles the Elizabeth Montagu, is less a source of scandal writing than a group with false pretensions to literary production and to leadership in critical taste. The Club plays coy games of scribal circulation – “if you’ll promise not to take a Copy, I think I’ll venture to trust you with the manuscript, – but you must be sure not to shew it a single Soul” – but is in fact lost in a wilderness of print, struggling to maintain some semblance of originality and authority in a literary field dominated by the poetic reputations of Pope, Swift, and Gay. Thus, the amateur poet Dabler laments, “I shall grow more and more sick of Books every Day, for I can never look into any, but I’m sure of popping upon something of my own.” Lady Smatter is ultimately defeated by the threat of the character Censor to propagate a libel against her by printing it. This unthreatening characterization of the coterie is belied, however, not only by the severity of the ridicule but also by Burney’s acquiescence in her advisors’ decision that the play ought to be suppressed. Even in the late 1770s, it seems, authors fighting for commercial success had to remain alert to the cultural power wielded by the coterie.15

One might view these satiric attacks as cheap shots aimed at a weakened and anachronistic target, but I would suggest that in their focus on the control of fame and on power over audiences they rather demonstrate the challenge that commercial authors could experience from the activity of such circles. With the emergence of interconnected groups like the Montagu‒Lyttelton coterie in the late 1750s, the patronage power of such coteries may have appeared stronger than ever before, as demonstrated by the example of Beattie above, and paralleled by the support this group marshaled through letter-writing and word-of-mouth for such authors as Sarah Fielding, Anna Williams, James Woodhouse, Hannah More, and Ann Yearsley. Coming to the negative attention of these networked coteries could also have formidable consequences, as I have argued elsewhere in the case of novelist, translator, and critic Charlotte Lennox. This potential threat, focused around the cultural capital of one’s public reputation, provides a suggestive backdrop to conflicts Montagu was increasingly engaged in regarding the ownership of public “character,” however content she might insist she was to imagine her “praises … rid[ing] about the World in every bodies pocket.”16 Specifically, do an individual’s image and reputation rightfully belong to her or his coterie, whose responsibility it is both to represent and defend them, or are they the property of an enquiring public, and therefore in effect fair game for the commercial print trade? This conflict of literary and media value systems came to a head in the confrontation of two culturally powerful individuals, Elizabeth Montagu and Samuel Johnson, over the latter’s 1781 “Life of Lyttelton.”

Johnson and the coterie once more

Burney’s representation of the “Esprit Party” in The Witlings, had it been performed in 1779, would have presented for the public’s entertainment a picture of the world of coterie authorship and criticism as a feminized and impotent one. This, in fact, is very much the representation of the coterie author implicit – and often not-so-implicit – in Samuel Johnson’s biographical and critical prefaces to the English poets, commonly known as the Lives of the Poets, which he was composing in tandem with Burney’s drafting of her play. The Johnson of the Lives, of course, was no longer the relatively unestablished newcomer of the failed Rambler patronage campaign of the early 1750s (see Chapter 2). The period of the Rambler was followed closely by the completion of Johnson’s Dictionary of the English Language and its author’s critique of the Earl of Chesterfield as patron. In his much later account of Johnson’s famous letter to Chesterfield of 1755, Boswell reports William Warburton as conveying a compliment to Johnson “for his manly behaviour in rejecting these condescensions of Lord Chesterfield, and for resenting the treatment he had received from him, with a proper spirit.” If to be manly, in the eyes of Johnson’s author-peers, was to defend one’s dignity and independence in the face of an aristocratic patron, the efforts of would-be female patrons, even when fronted by a one-time colleague such as Elizabeth Carter, would have posed an even greater threat to that manly autonomy.17

That such gendered terms are prominent in an account transmitted some thirty-five years later illustrates how embodied coterie forms of patronage shared by Chesterfield, Carter, and Talbot – speaking and writing letters to endorse an author’s character and work – were increasingly feminized over the course of Johnson’s career, while his own writing was seen as articulating an emerging professionalism of the print-based author that came to be figured as “manly.” I draw here on the argument of Linda Zionkowski, in Men’s Work: Gender, Class, and the Professionalization of Poetry, 1660–1784, that Johnson’s Lives of the Poets epitomize the decades-long emergence of a newly feminized model of the poet:

Johnson’s assertions about the kind of labour that poetry entails, the cultural status of poets, and the poets’ relation to audiences culminate in a professional identity for poets that fundamentally conflicted with the conduct of writers whose rank or gender proscribed engagement in commercial literary culture. In this way, the Lives offers an aesthetic complementary to the workings of the marketplace – an aesthetic that devalues other modes of literary production, circulation, and reception by representing them as appropriate only to amateurs – that is aristocrats and women.

Although Zionkowski does not explicitly reference the print trade or a coterie model of authorship here, her study as a whole traces a widening distinction between the two. Thus, it is instructive to consider the relationship between Montagu and Johnson as they interacted in an increasing number of dimensions, as patron and patronage broker, respectively, as mutually valued hostess and guest, as rival authors, and as critics of one another’s work.18

The implicit terms of Johnson’s acceptance of Montagu were that they be figured as equals presiding over literary cultures, however interpenetrating, that were centered in different media and different models of sociability. Johnson’s surviving letters to Montagu, dated from 1759 to 1778, show his acknowledgment of her role as patron – respectful, formally worded letters right from the start of their acquaintance recommend to her notice not only such women as the blind poet Anna Williams and “Mrs. Ogle, who kept the Musik room in Soho Square, a woman who struggles with great industry for the support of eight children,” but also the bankrupt bookseller Thomas Davies. Johnson further acknowledges Montagu’s exemplary fulfillment of the role; on behalf of Williams, for example, he returns “her humble thanks for your favour, which was conferred with all the grace that Elegance can add to Beneficence.” He also shows his appreciation for her as hostess and salonnière, combining his request for assistance to Davies with a mock-scolding: “Could You think that I missed the honour of being at your table for any slight reason? But You have too many to miss any one of us, and I am proud to be remembered at last.” Not only does Johnson willingly play the part of entertaining guest at the great lady’s table, but he is content to represent himself as a pale imitation of the conversational excellence of Montagu, who provides all things as a partner in dialog; as he tells Hester Thrale: “conversing with her You may find variety in one.”19

The situation becomes more complicated, however, when Johnson must acknowledge Montagu’s engagement as a literary critic and an author. Unlike his letters addressed to Montagu, which emphasize her benevolence and gracious hospitality, his correspondence and conversation about her can be more ambiguous in tone, suggesting that she shares the patron’s fault of desiring to prove herself the intellectual equal of the authors she hosts. Thus, her dislike of Evelina is a result of her “Vanity,” which “always upsets a Lady’s Judgement.” Boswell, in turn, reports Johnson taking on Joshua Reynolds, David Garrick, and the narrator himself in maintaining that Montagu’s 1769 Essay on the Writings and Genius of Shakespear “does her honour, but … would do nobody else honour” and contains “not one sentence of true criticism.” This rhetorical demarcation of Montagu as admirable female patron and hostess from Montagu as inferior intellectual and author is perhaps most explicitly articulated in the well-known exchange, recorded by Boswell, in which Johnson praises Elizabeth Carter, Hannah More, and Frances Burney as women in a class apart: “Three such women are not to be found: I know not where I could find a fourth, except Mrs. Lennox, who is superior to them all.” When offered the name of Montagu for inclusion in the group, Johnson replies, “Sir, Mrs. Montagu does not make a trade of her wit; but Mrs. Montagu is a very extraordinary woman; she has a constant stream of conversation, and it is always impregnated; it has always meaning.” Boswell consistently sets up discussions of Montagu’s conversation and benevolence by means of a critical comment which elicits opposing praise from Johnson; by contrast, he leads off with praise of Montagu’s intellectual work in order to have it qualified or denied by Johnson. In this way Boswell amplifies a distinction between his subject’s critical disdain for Montagu’s intellect and his praise of her verbal skills and philanthropy. While not every statement involves explicitly gendered language, Boswell’s strategies throughout are congruent with the above-noted description of Johnson’s letter to Chesterfield as “manly,” suggesting that the biographer subscribes to a gendered coloring of the organizational binary that separates the sphere of patronage and amateur, manuscript-based authorship from the public sphere of print professionalism.20

This interpretive framework organizes Boswell’s description of the response of Montagu and her friends to Johnson’s “Life of Lyttelton.” The passage illustrates how gender-associated terms can be used to imply the narrow-mindedness and inferiority of a coterie literary culture in contrast to one that appeals to a broad-based print readership:

While the world in general was filled with admiration of Johnson’s Lives of the Poets, there were narrow circles in which prejudice and resentment were fostered, and from which attacks of different sorts issued against him…. his expressing with a dignified freedom what he really thought of George, Lord Lyttelton, gave offence to some friends of that nobleman, and particularly produced a declaration of war against him from Mrs. Montagu, the ingenious Essayist on Shakespeare, between whom and his Lordship a commerce of reciprocal compliments had long been carried on … These minute inconveniencies gave not the least disturbance to Johnson. He nobly said, when I talked to him of the feeble, though shrill outcry which had been raised, “Sir, I considered myself as entrusted with a certain portion of truth. I have given my opinion sincerely; let them show where they think me wrong.”21

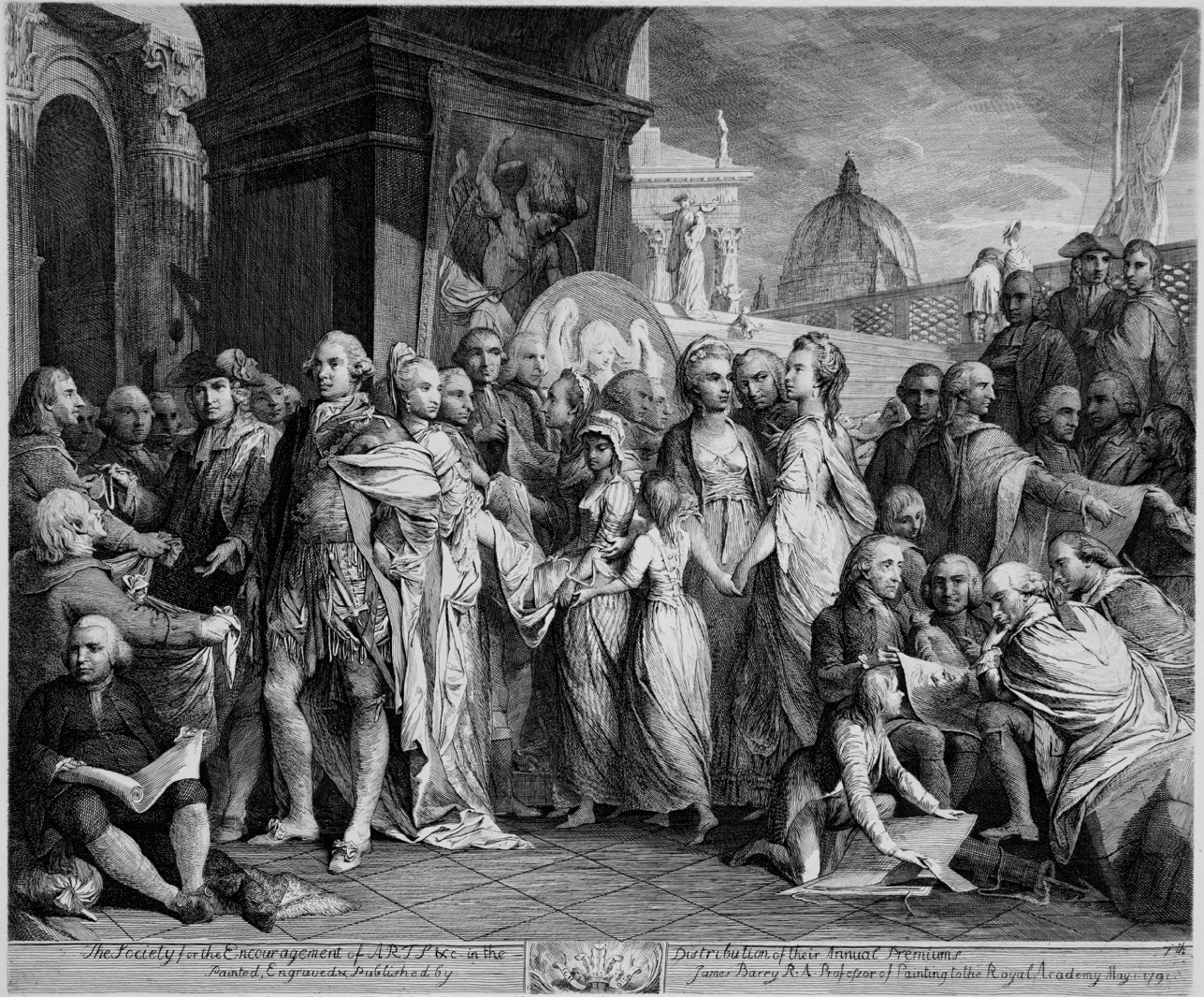

Boswell’s binary between a feminized sphere of patronage and a manly sphere of professional writing may be heavy-handed, but its terms were becoming general and virtually naturalized in the latter part of the eighteenth century, as indicated by James Barry’s fifth mural in his 1777–83 series The Progress of Human Knowledge and Culture, entitled “The Distribution of Premiums in the Society of Arts” (Figure 5.2). The painting features Montagu and Johnson as central actors but, significantly, they are not engaging one another directly. Rather, Montagu, as one of the Society’s patrons, presents the prize-winning work of a young girl to the late Duchess of Northumberland and the Earl of Percy. Behind her back, Johnson, in the role of “great master of morality,” as Barry terms it, is pointing out Montagu’s function as patron to the young Duchesses of Devonshire and Rutland, who are presumably being invited to follow this example. In Isobel Grundy’s view, this tableau is a representation of Johnson “patronizing the females of the patronizing classes.” I agree that he is indeed depicted as “relating … himself to a just-developing tradition of women patronizing women,” but the master moralist is speaking from a space outside the social sphere of patronage. Barry elaborates on his “reverence for [Johnson’s] consistent, manly and well-spent life” in that, despite his having been “so long a writer, in such a town as London,” he assists and furthers the careers of “all his competitors of worth and ability.” In other words, Barry’s Johnson is a disinterested observer and supporter of the transactions of patronage from his own position as a professional located squarely within the competitive commercial sphere. Johnson, then, was both source and instrument of a gendering process whereby his intellectual powers, authorial achievements, and moral stature in the combative professional realm were balanced against the sociable and charitable accomplishments of women such as Montagu in an ideally non-competitive social world.22

Figure 5.2 James Barry, “The Distribution of Premiums in the Society of Arts,” from A Series of Etchings by James Barry, Esq. from his … Paintings in the Great Room of the Society of Arts (1792). Montagu is just left of center, holding up a draped piece of cloth fabric, with Johnson just to the right at the rear, raising a pointing finger.

This gendering helped to entrench a growing divide between a professionalized print culture and an amateur culture of coterie exchange, obscuring how the latter engaged with the larger public through its own modes of production. But it should not be assumed that women of letters acquiesced in the division of literary culture along these lines. Montagu felt qualified to set her Essay on Shakespear alongside Johnson’s edition – at least, once she had determined that her project would be distinguished from his by her focus on generic questions and on a more particular examination of the plays, especially the histories. And even earlier, in 1763, she writes to Lord Bath, after what seems to have been her first tête-à-tête evening with Johnson:

he came early & staid late, so I had much of his conversation, He has a great deal of witt & humour, but the pride of knowledge & the fastidiousness of witt make him hard to please in books, so that he seems to take pleasure in few authors, for which I pity him. I believe he is not hard to please in conversation, for I hear he expresses himself delighted with the evening he pass’d here, & some of my friends tell me that since Polyphemus was in love there has not been so glorious a conquest as I have made over Mr johnson. He has many virtues, & witt & learning enough to make a dozen agreable companions, but a pride of talents always hurts & pains me. I do not love to see people use what God has given them as a light to shew the imperfect nature & defective compositions of man … 23

In short, Montagu does not accept Johnson’s combatively critical perspective toward authors and their productions as objective commentary; rather, she interprets it as a moral flaw.

Elizabeth Montagu’s concept of character

Like many of her contemporaries, Elizabeth Montagu was an avid reader of the character genre. While still a young woman seeking to secure her place socially and intellectually, she made enthusiastic use of such writings. She did so in precisely the manner intended by the popular seventeenth-century writers of Theophrastan character collections and by memoirists such as the Earl of Clarendon, who developed the art of combining the broad movements of history with sketches of the principal traits of its leading actors. As a newly married woman of twenty-five, for example, she sends to her wealthy patron, the Duchess of Portland, a “Character of the Lady of one of the Antient Earls of Westmorland; written by her Husband.” Montagu writes of the lady, “who methinks I see sitting at the upper End of a long table, with the fortification of a Ruff & farthingale,” that the Duchess “will rather honour her example than pitty her life.” Conversely, three years earlier, Elizabeth had sent her friend a satiric portrait of the late Duchess of Marlborough reportedly composed by Pope (presumably the Atossa lines from Epistle to a Lady making the rounds at the time, which Mary Capell copied into her poetry book as well). Although she classifies the portrait as “Entertainment,” Elizabeth reflects that “it may seem cruel to reflect on ye memory of ye Dead, but such great offenders should be made examples of Terror to those whom an unbounded prosperity lets lose [sic] to their own wills.” In 1750, Montagu writes to another friend about the memoirs of the Queen of Sweden that she has been reading: “her character was so extraordinary I had the curiosity to read them, but the historian is a bad writer as to stile, method, & facts … It is rather the History of a Savante than a queen, for the writer less regards her Political & Regal character than her litterary one.” Finally, in 1752, having embarked on an ambitious reading program guided by new associates such as her husband, Lyttelton, and West, Montagu sends a message to the latter:

I have sent you the Archbishop [Tillotson’s] life, I suppose you know that Mr Birch himself [the author] left it for you. I have read it thro’, & am charm’d with ye character, I hope it will make you read his sermons with greater pleasure, for I did not use to think you did intire justice to them. I never read of any Person for whom I had a higher veneration than this Prelate, he was truly a christian, … but you will find envy & malice pursued him thro life, & they say calumny & detraction gave him his deaths wound, therein I blame him.24

The character of the Tudor lady clearly represents one that the Duchess of Portland and Montagu herself, as young women charged with the governance of large and prominent households, know they must live up to; for all the facetiousness of tone, it serves a monitory and comparative function. Pope’s satiric portrait of the late Duchess is an “example of Terror,” perhaps, but a useful example for precisely that reason. “No fortune or State,” Montagu concludes, “can disfranchise a Person from the Duties of Society.” Montagu’s dislike of the memoirs of the Queen of Sweden is at once that of an experienced critical reader noting a failure to meet genre expectations and that of a female reader fascinated with the case of a woman of extraordinary power. And she knows exactly how to read the character of Archbishop Tillotson as a model both of true Christianity and over-sensitivity to the world’s opinion that cuts across gender lines.

One further pattern is important to my current argument: Montagu’s response as reader is inversely proportional to the selectivity of the sphere within which the character-piece circulates. She is most satisfied with the pieces that originate in an authoritative source – the subject’s husband, a great satirist, or an expert antiquarian – and to which she gains access through private means – whether contained by a sheet of paper enclosed in a letter or obtained directly from the author, as a pre-publication copy from the press. Indeed, in the case of the Pope satire, she cautions that secrecy must be maintained: “I must desire ye Dss & you will keep ye verses merely for yr own Entertainment for such are ye terms on which I obtaind them.” The character of the Queen of Sweden, encountered in a trade publication, proves a case of imperfect communication – what the reader desires is something other than what the hack author provides, and so she “cannot greatly recommend” the work. For Montagu, in other words, the character genre is inherently social, functioning best in a context of limited and selective circulation. It is a coterie form.

The very notion of “genre” at work here is a social one; in the influential formulation of rhetorician Carolyn Miller, genre is “social action.” While Miller’s emphasis is on the speaker, her insights can usefully be applied also to the reader as receiver and transmitter of a genre; thus Montagu’s confident deployment of the character arises out of “social motive,” as a product of her own sense of place and aspiration. The genre, in turn, “acquires meaning from [the] situation and from the social context in which that situation arose,” including, in this case, the rules of coterie exchange. Miller argues that studying rhetorical genres therefore reveals more about a cultural or historical period than about an individual rhetor or text. She goes further, citing Kenneth Burke, to suggest that in an age of instability, “typical [generic] patterns are not widely shared,” resulting in a “liquid” state of motives within and between individuals for the use of various discursive forms. This, I will suggest, was the fate of the character genre in the 1770s and 1780s.25

Montagu in the late 1740s and early 1750s knew very well what a character was, enjoyed and circulated examples for the entertainment and edification of her friends, and saw herself as enough of an expert to pronounce confident critical judgments on various attempts in the form. Yet twenty-four years later, in 1776, we find her writing indignantly to her friend Philip Yorke, Earl of Hardwicke, in the letter quoted as this chapter’s epigraph, about the character genre as “this new species of mischief.” In this case she is referring specifically to the characters written by the late Lord Chesterfield – short, witty sketches of the great men and women whom he had come to know intimately during his life as courtier and politician. The phrase echoes the famous locution of Samuel Richardson and the supporters of Henry Fielding – “this new species of writing” – as they promoted their mid-century innovations in prose fiction. What is for Montagu suddenly so new – and mischievous, apparently – about the character genre?

Several influential critical studies of the last decade have noted the multiple and shifting senses of the term “character” in precisely this period. Foremost among these, Deidre Lynch’s study of The Economy of Character in the eighteenth century has focused on the development of a novelistic notion of character that ultimately privileges individuality and deep interiority. On the way to this literary sense of the term, Lynch emphasizes the complex, punning amalgam of ideas of the physical mark, or legible sign, and of distinguishing traits invoked by the term “character” in the early decades of the century. For Lynch, an increasingly “typographical culture” focused on the exigency that readers of signs – whether imprinted on a page or in a face – be able to interpret character with accuracy, first, as a guide to an increasingly commercial society and then as a means of distinguishing themselves as sophisticated consumers. Lisa Freeman, in Character’s Theatre, contests Lynch’s claim that a model of unified, interiorized character was the dominant compensatory response to changing socioeconomic conditions, emphasizing rather the drama’s explicit embrace of character as multiple, disjunct, and often put on at will, if not downright hypocritical.26

Taking into account Lynch’s emphasis on character as a series of marks to be interpreted, as well as Freeman’s insistence that it was above all a construct and a performance, I wish also to ground my understanding of character in the eighteenth century in a broader, mediation-inflected notion of genre. This is because, as I have already noted, Montagu’s fundamentally social response to the character genre seems to be determined above all by issues of source, circulation, access, control, and readership. In this my approach resembles that of Hammerschmidt, cited at the start of this chapter, who argues that “wherever character was formulated and analyzed, it always emerged as an interface between media forms and their users that foregrounded its materiality and mediality.” Hammerschmidt’s emphasis on the inherent intermediality and social embeddedness of the process of character formulation in the familiar letter genre, requiring the participation of both writer and reader (and bookseller, in the case of Pope’s letters), applies equally to the conviction of Montagu and members of her networks that the meaning of a written character could not be understood without consideration of the context of its production and circulation.27

Indeed, eighteenth-century usages of the term “character” provided by the Oxford English Dictionary retain a strong flavor of materiality, emphasizing a mark or symbol or code and thereby doubly invoking not only the public typography of a print culture but also the secretive markings of clandestine or selectively circulated writings. Furthermore, both literal and emerging figurative senses are intimately tied up with the notion of character’s circulation as some kind of “text,” whether oral or written. Thus, the genre of the character, as “[t]he sum of the moral and mental qualities which distinguish an individual … viewed as a homogeneous whole” (first record of use 1660) becomes “moral qualities strongly developed or strikingly displayed; … character worth speaking of” (first exemplified in the eighteenth century), “an estimate … ; reputation,” and a “description, delineation, or detailed report.” All these senses, emergent in the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, invoke the idea of a public formulation that can be packaged for transmission or transmediation. In the correspondence of Montagu and her circle, we can trace their experience of this shift in the notion of character – from a distinguishing possession to a media phenomenon that was displayed, spoken of, and passed around – as an effect of an increasingly print-based mode of publicity, one which offered wider dissemination and potential influence but conversely an ever-decreasing control of access and interpretation. In tandem with the shift in Montagu’s relation to print publicity noted at the start of this chapter, her response to the use of print to disseminate character, over time, moved through cautious engagement, to embrace and even delight, to disillusionment and repudiation. This experience ultimately exemplifies how a shift of media balance can fundamentally alter the social meaning and function of a genre.

At the time that the young Montagu was privately circulating the characters of aristocratic ladies and archbishops, Elizabeth Carter was engaged in a character-transmission project of her own – the 1758 translation of the works of the Greek Stoic philosopher Epictetus discussed in Chapter 2. Although the translation began as a coterie discussion of the relation between stoicism and practical Christianity, print dissemination ultimately emerged as the means of most fully achieving the project’s goal of capturing stoic philosophy in a plainspoken style that would reach out to a broad audience. By “preserving [Epictetus’] genuine air and character,” what Thomas Secker described as “his own homely garb,” it was hoped that the translation would draw in “Many persons … who scorn to look into the Bible,” including “Fine gentlemen,” “fine ladies,” “critics,” and “Shaftsburian Heathens,” and thereby “be more attended to and felt, and consequently give more pleasure, as well as do more good, than any thing sprucer.”28 By broadcasting the character and ideas of Epictetus, Carter was of course simultaneously establishing her own public character for learning and virtue, which in turn led Montagu to seek out her friendship. Urging Carter to publish her poems in 1762, as we saw in Chapter 2, Montagu in turn emphasized the moral good that would be achieved through the widespread dissemination of Carter’s character – through “the pious, virtuous sentiments that breathe in all [her] verses,” the “proofs of genius,” and the “wit [that] is [her] own.” The efficacy of this strategic use of print is demonstrated in 1771 when Montagu writes to Carter that she will transmit her friend’s advice to her protégé Beattie, adding, “Your authority will go far, for he has a proper esteem & Admiration of your character. We often talkd of you. He wishd much to have seen you. I shewd him your Portrait and even that was a gratification to him.” Thus Montagu, in the days of the Montagu‒Lyttelton coterie, was not averse to the establishment of a carefully controlled public character that might not only be morally influential for readers of print but could also redound to the credit of the author herself. Her views are tested and modified in the late 1770s and 1780s, however, through the posthumous manuscript circulation and print publication of Lord Chesterfield’s characters, and then the high-profile commercial publication of Samuel Johnson’s Lives of the English Poets.29

Montagu, Hardwicke, and the threat to character

Montagu was proud of Carter’s demonstration that women could have characters that were, in the Oxford English Dictionary’s terms, “strongly developed or strikingly displayed; … worth speaking of,” giving the lie to Pope’s dismissive dictum that they were made of “matter too soft a lasting mark to bear.”30 The cultural influence of the leading Bluestocking women was undoubtedly broadened through the circulation of such print materials as Carter’s Poems, Montagu’s Essay, and perhaps even Scott’s The Female Advocate and the print of Samuel’s “Nine Living Muses of Great Britain.” As this chapter’s earlier discussion of changing representations of Montagu’s circle specifically, and of coterie sociability in general, has shown, however, when circulated far from its original meaning-making context, the social action performed by a character representation could become various and unstable. Thus, as Montagu grew older, she became increasingly concerned about the circulation of characters: who produced them, and by what means and to whom they were made available. This was much more than a preoccupation with her own reputation, or even with feminine propriety. In fact, her most fully developed discussion of these issues is with Lord Hardwicke, and it focuses on the circulation of the characters of prominent men who were close to them both.31

The interlocutor here is significant: as outlined in Chapter 1 of this study, the second Earl of Hardwicke had begun adulthood at the center of a high-profile literary coterie, and throughout his long life, which he devoted primarily to historical and literary pursuits, demonstrated a deeply coterie sensibility.32 This orientation was not entirely inward-looking: he energetically furthered the preservation of manuscript documents for the public good. Thus, much of his correspondence of the late 1770s and early 1780s details his efforts to obtain the papers of deceased statesmen for the newly founded British Museum, his private publication and distribution of collections of correspondence and state papers, his adjudication of the claims of various individuals requesting access to the papers held in the Museum, and his private printing and distribution of a new, hundred-copy edition of the Athenian Letters in 1781. In Hardwicke’s view, the public good merged seamlessly with the protection of his father’s reputation, a role he had taken on even before the 1770s. Shortly after the first Earl’s death in 1764, his son seems to have submitted a letter signed “Verax” to The Public Advertiser challenging the author of a recent “bulky Performance” on the libel law for going out of his way to “introduce his character of a very great Person, who is but lately dead, & whose Memory will ever be dear, not only to all that knew him personally, but to all honest & good Men of whatever Denomination.” Jemima Grey’s correspondence of 1766 reveals her serving as proxy, through Catherine Talbot, in approaching Archbishop Secker to in turn use his influence with the bookseller John Rivington to obtain changes to a life of the first Earl, published in the Biographia Britannica, that her husband found “very Unhandsome & Improper.” He has this matter, she writes, “seriously at heart,” and indeed the Hardwicke correspondence of that summer records extensive negotiations to have the biography altered to the family’s liking.33

Montagu and Hardwicke were contemporaries in age, and passing references in her correspondence suggest reasonably frequent contact, with even more of a social friendship developing in the later 1770s. Moreover, there was considerable overlap in persons who had been highly influential in the lives of both. Yorke had revered his father, the first Earl and longtime Lord Chancellor, whom Montagu in turn admired as a “steady star” necessary to the health of the state. Lyttelton was a peripheral associate of the Yorke‒Grey circle from the late 1740s, as noted in previous chapters, and entertained Philip and Jemima at Hagley in August 1763. As the first earl was dying later that fall, Lyttelton wrote to Montagu, “If I lose him I shall lose not only a dear and honord Friend, but the surest Guide of my Steps through the dark paths of that unpleasing political Labyrinth which lies before me.”34 Despite periods of political disfavor, William Pulteney, Lord Bath had also been an associate of the Hardwicke family until his death. The fates of the characters of these three deceased men became the subject of Montagu and Hardwicke’s shared concern. According to Lyttelton’s biographer, Hardwicke wrote to the late Lord Lyttelton’s brother William shortly after the appearance of the posthumous Works in 1774, expressing dismay at the edition’s falling short of his hopes for his friend’s memory. Then in late 1776, prompted by news of a set of manuscript characters left in Chesterfield’s papers, Hardwicke sent Montagu a list of them, marking those he had read and praising some, but focusing on those of his father as “very imperfect, and … dashed with some unjust Strokes of Satire” and of Lord Bath as “an unfair and severe One.”35

Montagu’s letter of response contains the passage that serves as epigraph to this chapter, an extended reflection on what she describes as “[one of] the most serious things in human life, the character a Man enjoys and the example he transmits.” Opening the discussion by declaring that this is “a subject in which [she is] interested, both as it respects a particular Friend, and the general interests of humanity,” she condemns the practice of circulating characters as discrete works, decontextualized from a full biography against which the attribution of qualities can be tested:

It has long been usual with Historians, after relating the actions of a Mans life, to draw up his character; even in that case, there is room for partiality, the Writer may present us with a flattering resemblance, or a Caracatura, but still the Portrait must be formed on the features of the original, and something of the result of the whole in the general air must be renderd; but in these unconnected, independent Pieces there may be the most unfair, and unjust, and unlike representation, and if the next generation should be as much more idle and lazy than the present, as the present is than that which preceded it, posterity will take its opinions of their Predecessors chiefly from these little works.

As would soon be the case with the undistinguishable features of the “Nine Living Muses” print in the 1778 Ladies New and Polite Pocket-Memorandum Book, the character genre, when detached from a meaningful social and textual context through fragmentation, indiscriminate circulation, or historical distance, becomes a travesty.

Of course, Montagu herself enjoyed reading such fragmentary character sketches earlier in her life, as my examples have shown, and Chesterfield’s characters continued in that vein. Montagu’s reference to increasingly “idle and lazy” generations, however, suggests that she views this phenomenon of genre and mediation as a recently emerged ethical issue for both authors and readers. She goes on to make this explicit:

I look upon the toleration, and indeed encouragement given to Calumny to be one of the worst symptoms of the declining virtue of the age. When I was young (it is a great while ago) character was considerd as a serious thing; to attack it was thought the greatest outrage of an enemy; to receive any damage in it, the greatest of injuries, and the worst of misfortunes. Now no one seems interested for his own character or for that of his Friend, and indeed the daily libel has levelled all distinctions.

The “daily libel” – in other words, that propagated by newspapers – at least disappears from readers’ minds “for want of attick salt” – thus “the Libel of Monday, is become too stale for Tuesdays use, and these Calumniators, like the flesh fly, live but a day.” The real threat is when persons of wit and elevated social standing such as Chesterfield invest their talents and authority in the genre without ensuring that access remains restricted, thereby enabling the damage done by indiscriminate circulation: “Indeed,” Montagu concludes, “if it shall become a fashion for Men of Witt and of distinguish’d situations, to leave behind them malicious libels on their Contemporaries, this new species of mischief will be more serious and important.”36 What Montagu is describing, overall, is a crisis of the character genre as social action, an “instability of motives” (to return to Burke’s phrase) which has produced an abuse of the genre by creators and by the heirs and booksellers who transmediate their creations into print.

Montagu’s first impulse at such abuse of character is to shut down circulation altogether. Thus, later in the same series of letters, when Hardwicke has sent her a manuscript transcription of the character of his father, she returns it with the avowal: “Mrs Montagu presents her most respectfull compliments to Lord Hardwicke, & assures him, she has never communicated the character to any one, but kept it under lock & key till she could send it by a safe hand, or have an opportunity of delivering it into his Lordships. She wd not venture to send it by her Servants, or had returnd [it] immediately.” She declares that this example “renders [her] more than ever averse to this species of writing.”37 Montagu and Hardwicke concur that the character of a great man (or woman) is for the perusal of a highly restricted audience; only those who have had knowledge of the original or who know how to obtain that knowledge can judge the validity of the copy. In the new media regime of print journalism, the genre had better disappear altogether rather than risk indiscriminate circulation and a travesty of its established functions of exemplification and entertainment for the knowing few. In this, Montagu and Hardwicke in fact pre-empted the novelists and playwrights who in a few years would condemn elite coterie writers who allowed their calumnies to be transmitted to the scandal-papers.

Coterie values and Johnson’s Lives of the Poets

The stage is now set for a consideration of Johnson’s Lives of the Poets as provoking a confrontation between the coterie ideal of character as properly for the “interested” – in other words, as the property of a man and his immediate circle – and the print-based view of character as a public artifact, at once a valuable commodity in the commercial trade and a fit object of observation and judgment for any reader, contemporary or succeeding, who might take an interest in it. In the previous chapter, I discussed the response of Richard Graves, member of William Shenstone’s coterie, to Johnson’s “Life of Shenstone.” Here, I will focus particularly on Montagu’s response to Samuel Johnson’s “Life of Lyttelton” as representative of the position of a number of individuals invested in the coteries I have been discussing in this study. Montagu again received this life from Hardwicke, in the form of an advance copy, in early 1781. In his cover note, Hardwicke announces, “A more unfair and uncandid account I never read, and he (the Dr. [Johnson]), deserves to be severely chastised for it.” Hardwicke’s assessment of Johnson’s motive for “attacking” Lyttelton is that “the man’s head is turned from the pay of booksellers, and the puffs of some literary circles.” The unmistakable implication that status distinction has been violated is typical of the recorded responses of close adherents of Montagu and Lyttelton, as is Hardwicke’s declaration that “Ld L – tons character I will support to the last.”38

Subsequent readers schooled in the modes of a print literary tradition, particularly in valuing “objective” criticism, have puzzled over the strength of the reaction against the “Life,” which Reginald Blunt described in 1923 as “short and by no means scathing.” It is helpful to consider Martine Brownley’s contextualization of Johnson’s Lives in relation to the tradition of the character genre, wherein they are a departure for their representation of idiosyncratic, mixed characters, and for their interest in what we would consider psychological depth. In her formulation, Johnson “evolves a form in the Lives uniquely suited to convey his own beliefs about human character,” including “his lifelong recognition of the contradictions and complexities of men.” This notion is in keeping with the model of the self as intricate and individualized that Lynch has identified as increasingly prominent in the latter years of the century, but it is inimical to the investment of Montagu’s circle in an older model of character as a “homogeneous [and exemplary] whole.” Given the values of the literary coterie, by which literary production cannot be disentangled from the social relations within which it is embedded, and whereby the general advancement of the group and its members is sought, such print exposure of “contradictions and complexities” was perceived not as objective analysis but rather as petty or even cruel calumny, perpetrated by a coward on a man who could no longer defend himself. That the principal flash point was Johnson’s use of the condescending phrase “poor Lyttelton” to describe his subject’s humility of address toward the reviewers of his Dialogues of the Dead could not be a surprise given the kind of cultural authority wielded and prized by such coterie leaders as Montagu, Hardwicke, and in his day, Lyttelton. The issue is epitomized by William Weller Pepys, defender of Lyttelton against Johnson; he reports to Montagu after the two men’s confrontation at Streatham Park that Johnson at one point “observ’d that it was the duty of a Biographer to state all the Failings of a Respectable Character,” at which point Pepys “never long’d to do anything so much as to assume his [Johnson’s] Principle, & to go into a Detail which I cou’d suppose his Biographer might in some future time think necessary.” As a gentleman, it is implied, he desisted – just as Johnson would have done had he respected the proprieties of literary sociability.39

On the front line for the Montagu party, then, was Pepys (later Sir William), a man of learning and conversation thirty-one years Lyttelton’s junior, who had nevertheless become his friend in the 1760s and happened to be at Hagley at the time of its owner’s sudden fatal illness in 1773. It was through Lyttelton that Pepys had become acquainted with Montagu, and Lyttelton on his deathbed asked Pepys to inform her of his death. During the 1770s, Pepys and Montagu became correspondents and regular visitors; in her letters to him we at times see a return of the sparkling wit to which she rose in writing to Bath and Lyttelton in the days of that coterie. Pepys felt personally the slight to Lyttelton; he writes to Montagu of his frustration “not that Johnson shou’d go unpunish’d, but that our dear & respectable Friend shou’d go down to Posterity with that artful & studied Contempt thrown upon his character which He so little deserv’d,” and that “a Man Who (notwithstanding the little Foibles he might have) was in my Opinion One of the most exalted Patterns of Virtue, Liberality, and Benevolence, not to mention the high Rank which He held in Literature, shou’d be handed down to succeeding Generations under the Appellation of poor Lyttelton!”40 Also a frequent guest at Streatham during this time of Johnson’s intimate friendship with its proprietors the Thrales, Pepys was challenged by Johnson to an after-dinner debate which, according to Frances Burney’s account in her journal, began over dinner and lasted to tea-time, when Hester Thrale insisted it stop. In Burney’s narrative, the quarrel is carried out as though it were a duel of honor. Johnson cries, “I understand you are offended by my Life of Lord Lyttelton, what is it you have to say against it? come forth, Man! Here am I! ready to answer any charge you can bring,” while Pepys is praised for “utter[ing] all that belonged merely to himself with modesty, & all that more immediately related to Lord Lyttelton with spirit.”41

But this was only the most dramatic of the Montagu-connected defenses. Robert Potter, a clergyman and translator who was chronically in need of financial support and whom Montagu was assisting at this time with a couple of publishing projects, produced an essay entitled An Inquiry into Some Passages in Johnson’s Lives, which in a measured tone critiqued Johnson for the “spirit of detraction diffused so universally through these volumes” before focusing on the author’s uninformed and insensitive criticism of lyric poetry in particular. Although Reginald Blunt has argued that Montagu has been unfairly represented as the one who “led the attack” on Johnson, Potter in this case certainly discussed the projected work with his patron, writing in December 1782:

Were [Dr. Johnson] content to be only dull in himself, one might bear with him; but he is the cause also that dullness is in other men, through the undeserved reverence which the public has long been taught to pay to his dictates; nay, what is worse, with a gigantic insolence he pulls down established characters, and suffers no fame to live within his baleful influence.

He later reports, “It is a singular pleasure to me to find that my little publication is so well received; I must think the better of the Public, a sensation agreeable enough, for favouring an attempt to vindicate the injured reputation of persons who were ornaments to their country: I have done an act of justice, I have obliged some persons whom I wish to oblige, I have gratified my own mind, which is the finest thing in the world, and, what weights with me more than all this, I am honoured with your approbation.” And according to his biographer Clarence Tracy, Richard Graves was “spurred into action” by Montagu, in defense of Shenstone against Johnson’s biography of that poet, to write his 1788 Recollections (see Chapter 4).42

While Montagu declares to Pepys, in reply to his initial report of the encounter, that “tho I am angry with Dr. Johnson I would be angry and sin not,” and that she has therefore attempted to delay publication of a multi-authored personal satire against the man until after his death, the experience clearly left a deep impression. She returns in her correspondence to Johnson’s approach to biography again and again. Still in 1781, speaking to Pepys of her nephew and adopted heir, she hopes, “May he be worthy of the esteem of such as Mr. Pepys, and the envy, and the malice, and the railing, of such wretches as Dr. Johnson, who bear in their hearts the secret hatred of hypocrites to genuine virtue, and the contempt of Pedants for real genius.” She writes to Vesey in the next year, “Pray have you read Dr Wartons 2d Vol on ye Writings &c of Pope, The depth of judgment & learning ye candor of his Observations make this work ye most perfect contraste of johnsons criticism that can be imagined. The Muses guided ye pen of Dr Warton ye furies ye porcupine quill of Johnson.” In these comments she consistently interprets Johnson as actuated by personal spite rather than manly truth-telling, as Boswell would have it, or financial gain, as Hardwicke suggested. In a final statement, written upon the occasion of Johnson’s death three years later, Montagu returns once more to the same theme: “The news will inform you that Living Poets need not fear Dr. Johnson should write their memoirs after they are no longer able to refute Calumny. I hear he dyed with great piety and resignation; and indeed he had many virtues, and perhaps, ill health and narrow circumstances gave him a peevish censorious turn.”43

It seems, then, that Johnson’s “Life of Lyttelton” came as the culmination of a sequence of events in which Elizabeth Montagu was led to reconsider the use of print to make character public. The problem was not only idle and lazy readers but authors motivated variously by malice, if they were “of distinguish’d situations,” and by “envy” or “the pay of booksellers,” if they were of more humble rank. All were quick to be exploited by an undistinguishing press ready to “[give] Encouragement … to Calumny.” In turning away from print as a suitable medium in which to preserve and disseminate character, Montagu was not able to quench the thirst of readers for access to the foibles and contradictions of prominent men and women or the willingness of publishers to provide lives, memoirs, and recollections – as the market in biographical accounts of Johnson himself was soon to demonstrate. But rather than simply instigating the “feeble, … shrill outcry” of a “narrow circle[ ] in which prejudice and resentment were fostered,” she was deliberately aligning herself with other cultural figures of her day in what they perceived as an ethical, if futile, stand against a commercial print industry only too happy to exploit character to suit degraded tastes. Montagu was an active player in a high-stakes game of media choice and control. Not only that, she was astutely commenting on the instability of a system of literary values undergoing rapid, media-accelerated change. While we, imbued with beliefs in an unrestricted printing press and in objective criticism, may find distasteful the notion of limiting access to the characters of the elite, for Montagu, whose literary values had been formed in the context of the coterie, it was “a subject in which [she was] interested, both as it respect[ed] a particular Friend, and the general interests of humanity.”44 Montagu’s concerns over the practice of the character genre, then, bring into sharp focus the questions of status, authority, privacy, audience, access, and even the meaning of a life that swirled around media interface in her time – and continue to do so today.