Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgements

- Preface

- Introduction: Looking after Lesbian Cinema

- 1 The Woman (Doubled): Mulholland Drive and the Figure of the Lesbian

- 2 Merely Queer: Translating Desire in Nathalie … and Chloe

- 3 Anywhere in the World: Circumstance, Space and the Desire for Outness

- 4 In-between Touch: Queer Potential in Water Lilies and She Monkeys

- 5 The Politics of the Image: Sex as Sexuality in Blue Is the Warmest Colour

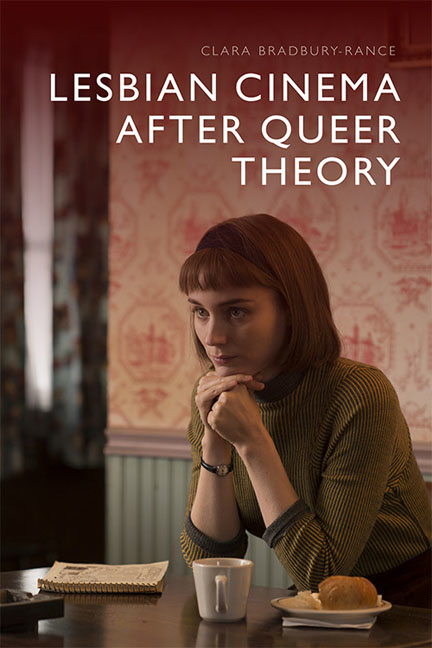

- 6 Looking at Carol: The Drift of New Queer Pleasures

- Conclusion: The Queerness of Lesbian Cinema

- Notes

- Filmography

- Bibliography

- Index

6 - Looking at Carol: The Drift of New Queer Pleasures

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 14 December 2019

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgements

- Preface

- Introduction: Looking after Lesbian Cinema

- 1 The Woman (Doubled): Mulholland Drive and the Figure of the Lesbian

- 2 Merely Queer: Translating Desire in Nathalie … and Chloe

- 3 Anywhere in the World: Circumstance, Space and the Desire for Outness

- 4 In-between Touch: Queer Potential in Water Lilies and She Monkeys

- 5 The Politics of the Image: Sex as Sexuality in Blue Is the Warmest Colour

- 6 Looking at Carol: The Drift of New Queer Pleasures

- Conclusion: The Queerness of Lesbian Cinema

- Notes

- Filmography

- Bibliography

- Index

Summary

Bringing this book's case studies together as one corpus has revealed the fre-quently and even inherently imitative structure of desire's figuration. Erotic identities are constituted through identification. The lesbian finds herself mediated through culture, her sexuality defined only through a depleted patriarchal vernacular, a performance of a sexual role or a culturally imag-ined style. The cinematic image, even as it promises to provide ‘evidence’, always threatens to reveal itself as that which has been an illusion. In Blue Is the Warmest Colour (Abdellatif Kechiche, 2013), Emma's sexuality first takes form in Adèle's mind as masturbatory fantasy before any acquaintance has been made and is then reduced to the iconic image of her blue hair that figures desire on her behalf for the rest of the film. The ensemble switch in Mulholland Drive (David Lynch, 2001); the titular character's death in Chloe (Atom Egoyan, 2009); the surveillance aesthetic in Circumstance (Maryam Keshavarz, 2011): these are all ways in which, through a constant preoccupa-tion with revealing and withholding, each film exposes, and then threatens to shield, lesbian desire.

Studies of lesbian cinema have increasingly shifted conversations away from the intentionality of desire central to psychoanalytic film theory. In her book Lesbianism, Cinema, Space (2009), Lee Wallace foregrounds the spatialisa-tion of desire, dividing up her chapters in order to account for the lesbian set, mise en scène, location, edit and diegesis. Conspicuous in its absence from this list is the gaze. Such a term seems to turn back time, invoking primarily the active desires belonging to the men who look in the classical Hollywood films forming the basis of Laura Mulvey's 1975 study of ‘visual pleasure’: The River of No Return (Otto Preminger, 1954); To Have and Have Not (Howard Hawks, 1944); Only Angels Have Wings (Howard Hawks, 1939); Morocco (Josef von Sternberg, 1930); Dishonoured (Josef von Sternberg, 1931); Vertigo (Alfred Hitchcock, 1958); Marnie (Alfred Hitchcock, 1964) and Rear Window (Alfred Hitchcock, 1954). When Linda Williams reviews the ‘afterlife’ of Mulvey's article, she begins by stating that, ‘in the early years of feminist film studies, it was difficult to write anything that did not cite’ it (2017: 465). Continuing in the next paragraph, Williams advises that ‘those were simpler days’ (Ibid.).

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Lesbian Cinema after Queer Theory , pp. 121 - 139Publisher: Edinburgh University PressPrint publication year: 2019