10 - Gower from Print to Manuscript: Copying Caxton in Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Hatton 51

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 18 January 2023

Summary

Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Hatton 51, a copy of the Confessio Amantis, most likely produced c.1500, contains a mistake. The penultimate line of fol. 181r reads “Or otherwkse yf it stode,” with the word “otherwise” misspelt with a “k.” This is not a scribal error but a printing error: Caxton’s 1483 edition of the Confessio (STC 12142) contains an identical mistake, the result of the “i” and “k” compartments in the type case being adjacent to one another and the compositor reaching for the wrong one while setting the forme. Hatton 51 is copied from the print and the scribe reproduces the mistake. Tasked with the lengthy job of copying the Confessio, the scribe of Hatton 51 would have had training enough to recognize and correct a misspelling in his exemplar. In choosing to copy it verbatim, the scribe preserves a mistake that could only have been made through the mechanical processes of print production. This odd moment reveals a scribe thinking carefully about what it meant to copy an exemplar that is printed. Copying a manuscript from a printed book was not unusual. As the number of printed books in circulation grew, it became increasingly typical for scribes to use them as exemplars. Indeed, as Curt F. Bühler puts it, “every manuscript ascribed to the second half of the fifteenth century is potentially (and often without question) a copy of some incunable.” Bibliographers such as Bühler, N. F. Blake, David McKitterick, and Julia Boffey have demonstrated the happy co-existence of manuscript and print, the ongoing production of manuscripts after the introduction of print, and the prevalence of manuscript-print hybrid books. They call into question Elizabeth Eisenstein’s notion that print supplemented and then supplanted manuscripts. Books such as Hatton 51 go further still to suggest that scribal practices were not just co-existing with print but being altered by it. As part of a larger project which examines how scribes were actively responding to a book market changed by the introduction of print, this essay demonstrates the multiple ways in which the Hatton scribe reproduced the look of the printed page, including its errors, in order to bring the styles and practices of print to his manuscript. In doing so, it demonstrates how the scribe was rethinking and redefining his role, and the role of the manuscript, in a shifting post-print book market.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

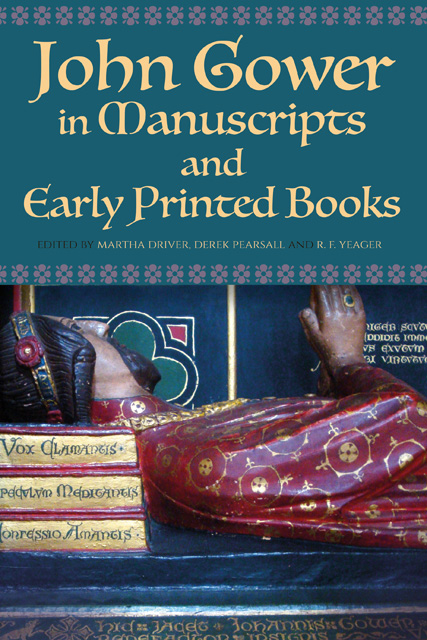

- John Gower in Manuscripts and Early Printed Books , pp. 189 - 200Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2020

- 1

- Cited by