Book contents

- Interfaces and Domains of Contact-Driven Restructuring

- Cambridge Studies in Linguistics

- Interfaces and Domains of Contact-Driven Restructuring

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Figures

- Maps

- Tables

- Acknowledgments

- 1 Questioning a Long-Lasting Assumption in the Field

- 2 The African Diaspora to the Andes and Its Linguistic Consequences

- 3 Reconciling Formalism and Language Variation

- 4 Variable Phi-Agreement across the Determiner Phrase

- 5 Partial Pro-Drop Phenomena

- 6 Early-Peak Alignment and Duplication of Boundary Tone Configurations

- 7 Final Considerations

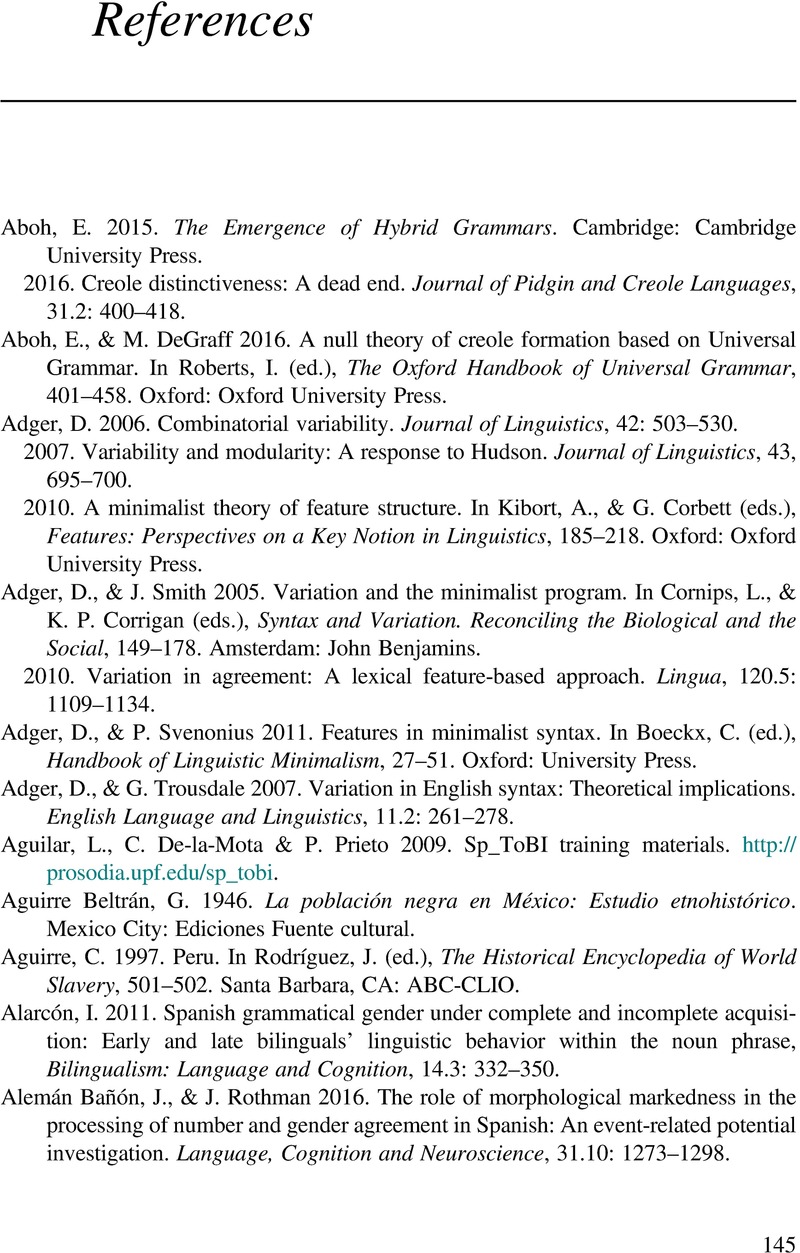

- References

- Index

- References

References

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 21 October 2021

- Interfaces and Domains of Contact-Driven Restructuring

- Cambridge Studies in Linguistics

- Interfaces and Domains of Contact-Driven Restructuring

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Figures

- Maps

- Tables

- Acknowledgments

- 1 Questioning a Long-Lasting Assumption in the Field

- 2 The African Diaspora to the Andes and Its Linguistic Consequences

- 3 Reconciling Formalism and Language Variation

- 4 Variable Phi-Agreement across the Determiner Phrase

- 5 Partial Pro-Drop Phenomena

- 6 Early-Peak Alignment and Duplication of Boundary Tone Configurations

- 7 Final Considerations

- References

- Index

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Interfaces and Domains of Contact-Driven RestructuringAspects of Afro-Hispanic Linguistics, pp. 145 - 168Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2021