The Constructive Power of Non-Knowledge

The British and French Empires in the Mediterranean were trade empires. They were mercantilist empires. On the one hand, this is obvious. On the other hand, however, to describe a form of prevailing economics as “mercantilist” does more to start a series of questions than to clarify matters. Without entering into the ongoing and renewed debate about the term “mercantilist” itself and its usefulness, I will define it here as the “nationalization of economics.”Footnote 1 And I will treat the question of nationalization as an epistemic one: It is the crystallization and hardening of the distinction between “internal” and “external” that defines this form of economics. But while most research on mercantilism concentrates either on trading practices or, within the history of ideas, on theoretical treatises that discuss matters such as bullionism or the balance of trade, here I take a step backwards. I first start with the central perceptional structure organizing all mercantilist communication, the distinction between the trade of “our” nation and that of others. Without that, Thomas Mun could never have calculated a balance of trade, nor could any import/export regulation have functioned. The hardening of that distinction, and its exposition in everyday trading communication, is a distinctive phenomenon of the period, as comparison with the Middle Ages will demonstrate. Only in the second stage, will I address ideas and discourses, investigating the general frames of thought of Empire that governed and directed the differing French and British conceptions of rule in and of the Mediterranean. In so doing, I follow the heuristic assumption that those empires themselves emerged via a bottom-up process that involved the continual specification of “nation non-knowledge,” through asking and answering questions about the national. This happened in an osmotic relationship with framing and circumferential imperial discourses, but this imperial thought was changing more slowly and it remained detached from everyday practice.

The national form of distinction that began to dominate Mediterranean trade was a question of operative (non-)knowledge, while imperial discourse was moving toward epistemic knowledge. On a very basic level, one had to know the nation to which a given ship, sailor, passenger, cargo or captive being ransomed by pirates belonged. The nationalization of economics meant, first of all, the transformation of something that had hitherto been in a state of nescience into a specified unknown. From the highest level of imperial bureaucracy – the royal courts, the admiralties – to the London port officers and the Chambre de commerce in Marseille, the question “what nation is he or it from?,” was a constant traveling companion for each man on a ship and each consul in the Mediterranean port cities, and it dictated everyday decision-making and politico-economic planning. The British and French did not ask about the national in the same way, however, and that national distinction was embedded in different general frames of thought. In the following, I compare both trade empire mercantilisms from the perspective of “non-knowledge about the national.” This is an approach different and complementary to macro- and microhistorical research on imperial economics in general and on Mediterranean commerce in particular. Macro-historical approaches tend to presuppose the category of the nation in their narratives: “The Dutch,” “the French” and “the English” conduct trade; but how those categories were themselves new, and to some extent arbitrary, and how they created paradoxes and were an object of continual discussion and interrogation, is not taken into account.Footnote 2 Microhistorical works, on the other hand, are familiar with how to look into the concrete realities of investigation into the national, but they are usually less interested in administrative standards and practices in addition to the overarching imperial concepts that were still the rules of the game. Even for a single actor, “the national” was intrinsically important in a myriad of interactions. The emphasis is put here on the osmotic relationship between practice and theory. I combine the macro and the micro, and focus on the mercantilism of empires. Because of that, other figures, groups and institutions play a minor role here, even if, in purely economic terms, they were very important. For example, the Greek, Jewish and Armenian trading diasporas (among others) were many things, but not imperial actors. There were no mercantilist norms, ports, or institutions that inquired in a comparable form into, say, Greek nation-non-knowledge in the Mediterranean.Footnote 3 What one may hope to learn by this third approach beyond the micro/macro opposition is, at first, somewhat tautological. It is how these empires, by defining and searching for the unknown national, were searching and finding themselves by defining what they are. I am interested in the constructive power of non-knowledge, something that might seem to be a paradox. The void of unknowns seems to be the least firm ground to build an empire upon. Yet it was precisely through the continual consideration of the question about the national and the nation abroad that the limits of the empires in question became visible at all. In addition, we must also consider the extent to which the category of “state” was connected to those of “nation” and of “economy.”

This has to be seen within what one can define as a two-level system of Mediterranean trade. On the first level, European merchants were, and saw themselves as, competing against each other. The second is the parasitic corsair economy. As the corsairs gained most of their whole societies” wealth from piracy or its functional equivalent, maintaining the threat of piracy but allowing its replacement by regular payments according to international peace treaties, states started to protect “their” merchants in different ways against their European and corsair competitors. The protection of merchants – in the Mediterranean cities as well as at sea – was thus an important economic factor on the first level, a transaction cost, shared between the merchants themselves and the states. It was also possible to borrow or “buy” a nation’s flag, or even use it without formal permission, and therefore take advantage of a given nation’s protection. This was actually in the interest of the states themselves because they obtained valuable duty payments from each shipowner or captain flying their nation’s flag. This could also be detrimental for a state, however, if there was abuse or the unauthorized use of a nation’s protection. From this, we see that the two-level system was transforming into a three-level system: competing European merchants, competing states/nations, parasite corsairs. How these various circles interacted with each other will be seen in the following.

Norms as Specifiers of National Non-Knowledge

In theory and in practice, the English normally distinguished between the particular interests of merchants and a general interest of “the nation,” while the French usually used “the state” in that second position.Footnote 4 That seemingly small, but fundamental difference in wording (“nation” vs. “state”) has to be kept in mind when studying the meaning of the national in the Mediterranean Empires’ trade organization and competition. The French increasingly conceived of their trading houses in the Mediterranean, protected by their consuls, as a part of the state’s extensions overseas. The internal/external distinction took the form of an invisible appendage of state borders abroad. The English mercantilist conception of trade did not subordinate merchants’ activities to the state as much, but it did integrate forms of state power into their commercial network. English merchants acted more as agents of their nation than their state. While this is a difference encountered throughout all sources in the following, in a striking parallel the fundamental guiding standards emerged for both England and France around 1650/60.

Defining the Unknown

A very important process of reform and legislation around 1660 provided the pivotal moments for England and France, when respective shifts occurred, turning economic activities in a state of nescience about “nation” into one where the nationality (of merchants, sailors and ships) became the central specified unknown.

England

The 1660 Second Navigation ActFootnote 5 and the 1662 Act of Frauds,Footnote 6 together with the system of peace treaties and sea-passes, marked a decisive point of the nationalization of English seafaring in the Mediterranean. The first 1651 Navigation Act had been an “experimental law” to some extent, and, even though it had been strongly influenced by the lobbying of the Levant Company, only with the 1660/62 combination of laws did legislation achieve enduring decisiveness and incorporate important clauses concerning the southern trade.Footnote 7

This occurred through the transformation of a state of nescience embedded in former practices into specifications of non-knowledge about the nationality of sailors. Those regulations required that English merchants who wanted to import from or export to the Mediterranean “beyond Malaga,” had to provide an English ship with a minimum of two decks, armed with sixteen guns with at least thirty-two men, with the master and at least ¾ of the crew needing to be English.Footnote 8 The Navigation Act was rigid insofar as it allowed the seizure of foreign ships and their goods; the Act of Frauds dealt with the discipline and fine-tuning of the English ships themselves. The Mediterranean clause of the Act of Frauds only concerned the merchants who mostly conducted trade between Livorno, Spain, Portugal and England; the Levant Company – founded first as Turkey Company in 1580/81, and provided with a renewed charter in 1662 – was not affected. The Englishness of the company’s trade had already been secured by virtue of the company being closed to both foreigners and naturalized merchants until 1753. Even beyond the question of nationality, the company could only be joined by “meer merchants,” a restriction which remained firm despite frequently recurring complaints.Footnote 9 This stabilized the “Englishness” of the factories’ personal in the Levant (Constantinople, Aleppo, Smyrna) probably more effectively than the French did.Footnote 10

As for incoming ships until the 1740s – mostly between 1675 and the early eighteenth century – there were numerous cases when merchants applied to the Treasury to be freed from the one percent duty as they had lost men during the voyage due to several problems. These applications demonstrate how rigorously the surveyors of the Navigation Act and the Customs Commissioners controlled the ships in the English port cities. Mostly the problem was that the overall number of men was too small.Footnote 11

The one percent duty of the Act of Frauds concerned the character of the ship to be armed and suitable for defense, an armed condition that had to be maintained by English men for their English ships. To better understand the meaning of those norms, one has to take a short look at its pre-1660 history. Following 1617, when the Barbary corsairs attacked English ships and port cities on the Western English coast for the first time, the English government raised £40,000 over the next three years, in order to finance warships and men against this new threat.Footnote 12 The government seized the money through fixed sums demanded from the port cities in proportion to the amount of their trade which the London administrators had calculated from past customs records.Footnote 13 Some of the cities, apparently first of all London, but also Weymouth, decided to raise that money through a one percent duty on import and export customs. This was probably a repurposed technical practice that the port’s financial administration had utilized before.Footnote 14 Others simply collected the required money from their merchants. Nearly all complained that the London center’s pretended knowledge of local trade was false and outdated, not least because of the current losses caused by the corsairs. The local character of the duty also created several unintended problems within the inner-English competition of the outport cities.Footnote 15 Perhaps because of that experience and due to intense discussions about the similar and related ship money (1635–1640),Footnote 16 the solution of a duty on imported and exported goods – even if still rememberedFootnote 17 – was not chosen during the 1620s and 1630s when the corsair problem was growing.Footnote 18 Only twenty-three years later, in 1642, just a year after the Long Parliament had prohibited Charles’ ship money, was the so-called Algiers (Argiers) duty adopted for that solution. It was, however, moved to the national level: the one percent was now to be levied in every English port city. While paying ship money for a royal navy was unpopular, such a duty to deal with the problem of piracy was accepted.Footnote 19 The 1642 solution decentralized the necessary knowledge about the amount of trade by ordering that local customs officers assess the levy according to current circumstances instead of calculating in London a proportion from past data meant to be valid for the present and through its national character; the unintended problems involving increased inner-English port competition were resolved. The 1642 duty act was extended several times.Footnote 20 While the money not used for ransoming captives was finally allocated to financing the navy in general, the 1659 overview of England’s revenues still listed the one percent duty.Footnote 21 Those solutions prior to 1660 were not linked to the rules of nationality concerning the ships and their men. It was first (in 1617–19) an answer based instead on the old feudal concept of the defense of the realm to which the cities had to contribute. The second step, the national tax of 1642, still had its roots of legitimacy in this concept of the defensive obligation of the king against the realm’s enemies and of his subjects to contribute the financial means to this aim.

The 1660/2 standards represent the sublimation and projection of the earlier defensive character of state violence against foreign threats into a mercantilist internal/external distinction by inquiring into and controlling the national character of commerce. Paragraph 33 of the Act of Frauds set minimums on the type of English ship capable of being a “swimming defence machine” on its own. Now the duty worked by forcing merchants to use such “swimming little exclaves of England” in the Mediterranean – if not, the duty served as a contribution to necessary convoy shipping sponsored by the crown. The distinction between foreigners and Englishmen, present in the ports and – at least theoretically – in the whole Mediterranean, pointed in an abstract manner back to those older roots of the defense of the realm. The economic and prohibitionist impact of the 1660/62 regulations was high. Transport between the Mediterranean and Britain was nearly completely monopolized by British ships.Footnote 22

From an epistemic point of view, the watershed of 1660/2 transformed the state of nescience about nationality into a central specified unknown. Non-knowledge about the nationality of each person on each ship in the Mediterranean was now of importance. It was specified as a problem and formed the central directive rules of Mediterranean commerce.

Eighteenth-century merchant handbooks transmitted those norm specifications as they had developed and practiced during the seventeenth century and following the 1701 Union. According to this, “British-built ships” were:

Ships of the Built of Great Britain, Ireland, Guernsey, Jersey, or the British Plantations in Africa, Asia, or America, and whereof the Master and three fourths of the Mariners are British, that is, his Majesty’s Subjects of Great Britain, Ireland, and his Plantations, and three fourths of the Mariners such during the whole Voyage, unless in Cases of Sickness, Death, etc.Footnote 23

A “stranger” was someone:

born in a foreign Country, under the Obedience of a strange Prince or State, and out of the Allegiance of the King of Great Britain; or a British Man born, who has sworn to be subject to any foreign Prince; though if such British-born Person, returns to Great Britain, and there inhabits, he must be deemed as British, and have a Writ out of Chancery for the same: And likewise the children of all natural-born Subjects, though born out of the Allegiance of his Majesty, etc. and all Children born on board any Ship belonging to, or in any Place possessed by, the South-Sea Company, are to be deemed natural-born Subjects of this Kingdom.Footnote 24

Evidently, similar to the Navigation Act itself, handbooks like that of Crouch reflect an already strong Atlantic orientation, but at the time of the handbook’s publication, the Southern-European trade still represented a good third of Britain’s foreign commerce and non-European trade only another third. London remained the uncontested British center of Mediterranean commerce,Footnote 25 and even more so, “as much of a third of New England’s adverse balance of payments with the mother country came from available returns from the Spanish, Portuguese, and Mediterranean markets.”Footnote 26

Probably nowhere else besides the kingdom’s naturalization records do we find more precise definitions of “Englishness/Britishness” and “strangers” than in these foreign trade records and merchant handbooks.Footnote 27

France

The French parallel to the English combination of the Navigation Act, Act of Frauds, as well as war and convoy shipping, were the almost exactly contemporaneous French reforms of the 1660s regarding Mediterranean shipping and the central port of Marseille. Most significant for our purposes was the prominent edict of March 1669.Footnote 28 This edict laid the ground for the status of Marseille as a free port and its monopoly over the Mediterranean for French imports and (less so) exports. If one reads its text, especially the first section, one sees how the edict uses the old concept of commercium, as exchange between peoples and “even the most opposite spirits who become conciliated through a good and mutual correspondence.” It stressed that, by royal grace, the act rescinded all former duties levied upon foreigners, specifying each old half to one percent duty annulled, and announced a message of liberty for all foreigners to come to Marseille.Footnote 29 Nevertheless, under the umbrella of that gracious liberty, the second part of the edict introduced a heavy 20 percent duty on all goods not shipped in French vessels. Works on economic history from Masson to Carrière have consistently stressed the prohibitive character of the edict due to that 20 percent duty.Footnote 30 Masson and Rambert called it “a kind of [sc. French] Navigation Act,”Footnote 31 and Carrière devoted a chapter to evaluating the economic rationality of the prohibitive 20 percent.Footnote 32 One of the best informed contemporary historical accounts of French-Anglo-Dutch commercial competition from the sixteenth century until around 1700, Pottier de La Hestroye’s Mémoire sur le restablissement du commerce, highlighted the anchorage duty and the 20 percent duty as the only French means of protection, endangered by new peace treaties of Nijmwegen and Utrecht which allegedly granted the Dutch too many liberties. Colbert’s 1664/69 reforms and legislation was placed here in exact parallel to the English and the Dutch prohibitive measures.Footnote 33

Without doubt, this is the perspective of the state-centered discourse of political economy. Today, scholarship less interested in inter-state competition than in the complex realities of merchant networks, sometimes hidden by the perceptional framework of state simplifications, has come to appreciate the edict’s impact on attracting foreigners, foremost Armenian and Jewish colonies – but there is a risk of overlooking the second, prohibitive part of the legislation.Footnote 34 Many of the foreigners would probably not have come to Marseille if French trade had not been monopolized through the 20 percent duty. Their immigration was only partly voluntary, prompted by Colbert’s promises of liberty and freedom. This Janus-faced character of the French regulations of prohibition and free port establishment was different from the English Acts, and they likewise produced different results on the epistemic level of ignoring/knowing nationality.

The 20 percent duty had been advocated by Marseille merchants as early as 1658.Footnote 35 Their main interest was to exclude both foreigners and other French merchants, in addition to monopolizing the Levant trade in Marseille hands. In October 1662, Henri de Maynier de Forbin, baron d’Oppède, the first president of the Parlement de Provence, general counsellor to Louis XIV, and Colbert’s close collaborator in reforming the port of Marseille,Footnote 36 called together, by royal order, the aldermen and deputies of Marseille, as well as the deputies of the cities of Toulon, Antibes, St. Tropez, Fréjus, La Ciotat and Martigues in the Chambre de Commerce. After having collected several mémoires and advis on the “restablissement du commerce,” the deputies assembled between October 9 and 14 in the presence of the Duke of Mercœur, they deliberated over propositions and d’Oppède produced minutes of their discussions to be sent to the king.Footnote 37 Royal protection of commerce, they argued, should be granted by the renewal of the capitulations with the sultan and the installation and strong empowerment of the office of ambassador to Constantinople. Levantine commerce, they maintained, could not flourish without the state’s protection. The central measure of reform in this important 1662 collective mémoire was a proposal by the assembly and d’Oppède to introduce the 20 percent duty. Its aim would be to distinguish between the commerce of the Ponant and of the Levant and to prevent the English and French from conducting Levantine trade under “their own flag” instead of the “French flag.”Footnote 38 The whole compromise – 20 percent duty on the one hand, affranchissement and cottimo on the other – was already worked out at that time in collaboration with all other Levant port cities. In its general framework, the dual character of the standard was present from the beginning of the year-long decision-making process. The matter still took some time and discussion.Footnote 39 Once established, the duty formed a firm basis for Marseille’s Levantine monopoly to which the mémoires concerning Levant commerce addressed to Colbert and Seignelay in the 1670s and 1680s always referred as such.Footnote 40

The norms were successful. Of the 371 ships that departed between 1680 and 1683 from Marseille to the Levant, only ten were not French. The monopoly was enduring. In 1753, of 439 ships, there were only seven ships classified as foreign. This is even more decisive if we look just at France’s northern competitors (the English, Dutch and the French “Ponant”): Of the 16,210 ships that entered the port of Marseille from the Levant between 1709 and 1792, only 199 vessels (0.12 percent) were from Northern France or Northern Europe.Footnote 41 Vice versa, Marseille merchants were largely unable to participate in the Northern trade, owing to their ships not being competitive with those produced by the Northerners. From the point of view of Marseille, commerce had been partitioned between the passive Northern and Atlantic trade on the one side and the concentration on their active Levant trade on the other.Footnote 42 But one has certainly to distinguish shipping in the Mediterranean from shipping to and from the Mediterranean and the respective home country. Duties such as the 20 percent had a decisive impact on the latter, but less so on the former.

As opposed to the English standards, the French rules were at first rather imprecise about the “Frenchness” of a French ship. The 1669 edict expressed the norm in a quite complicated manner, articulating foremost the idea that all ships should sail directly from their outgoing Levant port to Marseille without stopping “in Livorno, Genoa or elsewhere,” and by charging all goods transported on foreign ships, even if French-owned, with the duty. It also formulated rules of registration with the French consuls in the Mediterranean port cities. The edict always used the legal distinction between “our subjects” and “foreigners [estrangers]” or between “foreign” and “French ships,” but it did not define what was to be considered a “foreign” as opposed to a “French” ship.Footnote 43 Only through evolution in practice and through further royal decrees – a 1681 ordinance and an elaborated 1727 declaration – did those definitions become more specific. Now, to be officially counted as French, a ship had to meet a quota of being at least ⅔ “really French.” By this qualification, French administration allowed foreigners to hold as much as a ⅓ interest in a French ship. This was different from the English case, where the body of the ship had to be not only British-built but also completely British-owned. Nevertheless, the question remained, what was to be counted as the corresponding “thirds” of a ship? Its sailors? The value of the ship itself? The goods it carried? From the 1681 Ordinance until the second decade of the eighteenth century this remained rather unclear, and therefore probably also not seriously debated or inquired into, either by the merchants, the state, or the Chambre de commerce.Footnote 44 The mixed character of free-port politics and of protectionism led to a higher degree of fluidity in the French case.

The French were also undecided about the best way to control the “floating Frenchness” in the Mediterranean. Early ordinances opted for centralizing administration and procedures within Marseille. Passports and congés were only to be issued by the Admiral and his officers in that port city, no consul, and not the ambassador in Constantinople were permitted to issue such passes, something that had been a common practice.Footnote 45 Several subsequent orders and mémoires relied solely on the consuls’ authority and their, by definition, decentralized administrative power. Consuls were called upon to examine ships and use their chanceries for the registration process.Footnote 46 This was in fact a question of the practical organization of epistemic processes: At what location can one best cope with ignorance? Where should knowledge crystallize? This is foremost a question of deciding between centralized and networked organizational structures for knowledge.

The differences between the rigorous demarcation of Britishness and the more fluid, evolving Frenchness of the merchant vessels might be explained by the different spirit and roots of the French legislation. Referring to the basic model of Mediterranean economics, defined by the two levels of inter-merchant and inter-European competition on the one hand, and the parasite economy represented by piracy/privateering on the other, the Colbertian standards were predominantly formulated from the perspective of the first level, while the British ones had largely been developed from the perspective of the second. While the French had known well of the Barbary problem for a long time, the 1669 Marseille edict evinced no genealogical roots in concepts of the kingdom’s defense, as the English legislation did. In fact, in that same year, 1669, Colbert transferred navy warships from Toulon back to Marseille and the French trade ships were likewise armed with cannons like the English. From the point of view of how the conglomerate of Versailles/Paris/Marseille and the London centers of administration thought and ruled, there was a different logic at hand. While we usually conceive of British trade politics as the spearhead of modern economic development, paradoxically, English mercantilism seems to have been far more “war-born,” while French mercantilism – despite being so decisively envisioned from the perspective of state – seems “trade-born.”

Mercantilist Paradoxes: Known Flags, Unknown Nations

From the point of view of inquiring into the epistemics of nationality, the interdependency between the two-level system and the emerging systems of security production – Ottoman-European and Barbary States-European treaties, sea-passes and armed naval support –Footnote 47 created several further administrative procedures. These were in constant interplay with the duty and customs system and the definition of the nationality of a ship, its cargo and its passengers.

National competition did not just need to play the protectionist card. It also pursued an expansionist agenda in terms of its nationality, and both lines of reasoning were partially contradictory. This becomes evident when analyzing the carrying trade and its gradual merging with practices of (ab)using a foreign flag. The carrying trade, the transport of other (“foreign”) merchants’ goods was of importance as was also the practice and possibility for “foreign” merchants to sail under the protection of one of the large naval powers.Footnote 48 The English plied the carrying trade in the Western Mediterranean to some extent, mostly along the Italian coast or along routes from Livorno to non-European ports beyond the Mediterranean. The French did both on a much larger scale, as the attractiveness of their protection grew from the late seventeenth century until a period that was once termed the “French reign” of the Mediterranean after 1740.

The traditional sign of being under the protection of a given “nation” was the ship’s flag. The stronger the risk of piracy was, and the more resources that had to be used for the protection of the ships flying one’s flag, the more it was in the interests of a given state to ensure that a ship flying a French flag was also a real French ship – whatever a “real French ship” might be. And as the treaty system between the Barbary states and the European powers had evolved and the corsairs became more or less willing members of an international maritime law system, they became increasingly interested in being certain what was a French or English or Dutch ship and what was not, if they met one at sea. This was a fairly simple logic, but it resulted in continual communication about ignoring, want and the need for knowledge about those criteria.

From the given interdependency between inter-European competition and the parasitic piracy economy, one can derive, grosso modo, a rule that in times of significant pirate activity, when the transaction costs for security were high, it was more advisable to keep the number of those who profit from a given state’s valuable protection small, so as to act in a protectionist manner against the practices of flag borrowing. In times when pirate activity was low, it became profitable instead for the flag of a given state if many merchants from other nations sailed under its protection through increased duty revenues, the concentration and attraction of flows of merchandise and the symbolic “branding” effect of apparent domination at sea. No early modern state and port accounting calculated those relationships in a mathematized form in our period, but the general rules of relationship and interdependency were clearly perceived and explicitly articulated.

The Normative Framework

The first English-Algerian peace treaty that contained detailed provisions concerning encounters between Algerian and English ships at sea and the control of the pass was concluded for the Crown by John Lawson in the same year as the Act of Frauds was issued, on April 23 / May 3, 1662. Under its terms, Algerians were to let every merchant ship whose captain could provide “a pass, under the hand and seal of the lord high admiral of England” sail in peace. If such a pass did not exist, the ship was, nevertheless, supposed to go free if the “major part of the ship’s company be subjects to the King of Great Britain.”Footnote 49 Following treaties repeat that latter clause.Footnote 50 The first order by which Charles II instructed the Lord High Admiral and the farmers of customs about the procedure is from November 23, 1663.Footnote 51 Following those orders, when a ship wanted to leave the port of London for a destination in the Mediterranean beyond Malaga, several necessary steps had to be taken: “The Surveyor of the Port where the Ship lies must go on board, and examine and survey her, and muster the Seamen; then he must certify in Writing under his Hand to the Collector of the Port, the Burthen and Built of the Vessel, the Number of Men, distinguishing Natives and Foreigners, the Number of Guns, what sort of Vessel she is, &c.” The Collector then prepared an affidavit in which the Master’s oath to the truth of all noted particulars was testified.Footnote 52 This affidavit was next transmitted to the secretary of the Admiralty who checked if the master of the ship had returned all past passes previously granted to him. The secretary had to ensure that the ship was English built or foreign but “made free,” that its master was the king’s “Naturall Subject” or “Forreign Protestant made Denizon,” and that “two thirds of the marriners” were the king’s subjects. The secretary then issued against the payment of a bond – in 1682 that tariff was £50 for ships up to 100 tons, £100 for larger shipsFootnote 53 – the sea-pass which the master had to give back after returning to the port.Footnote 54 The first register of sea-passes issued by the Admiralty dates from 1662, but the extant series is interrupted between 1668 and 1683, and again between 1689 and 1729.Footnote 55 The first register 1662–1668 and one may probably infer by that also the passes themselves, did not mention the destination of the ship.Footnote 56 In 1682, the practice changed; the officers of the Admiralty were now to use a table that contained the same scheme of entries. Still, the destination was not mentioned. Instead, an entry indicated the current location of the ship (“Place shee lyes at”).Footnote 57 After July 10, 1683, the alternative that it was sufficient if the “major part” of the men were English – which opened a door to case sensitive consular negotiations in favor of English ships without passports – was made invalid. Indeed, corsairs often rigorously seized ships in the early eighteenth century if they had no “proper Pass … altho she evidently appears to be a British ship” and confiscated their cargos.Footnote 58 The pass system had stabilized at least by 1682/83; the passes remained in use until the middle of the nineteenth century.Footnote 59

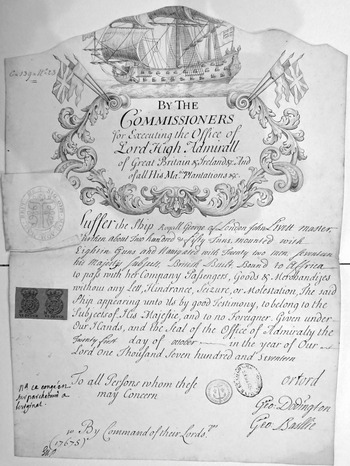

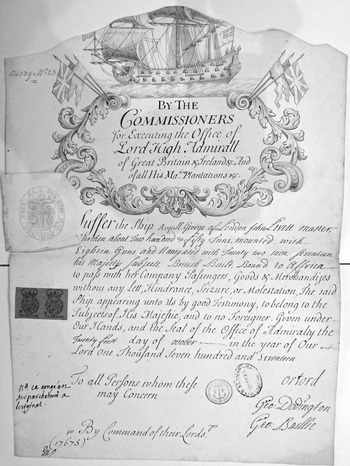

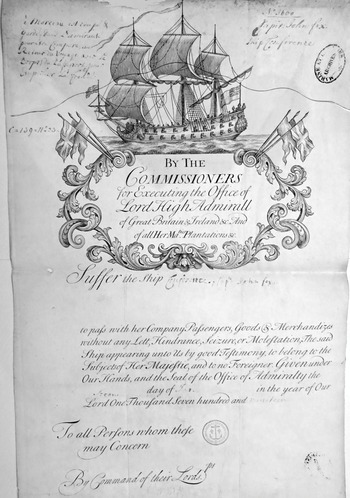

In 1717, a typical sea-pass issued by the commissioners of the Lord High Admiral read:

Suffer the Ship Royall George of London John Levett Master, Burthen about Two hundred & fifty Tuns, mounted with Eightin Guns and Nauigated with Twenty two men, seventeen his Majestys subjects, British Built, Bound to Affrica to pass with her Company Passengers, Goods & Merchandizes without any Lett, Hindrance, Seizure, or Molestation, The said Ship appearing unto Us by good Testimony, to belong to the Subjects of His Majestie, and to no Foreigner.Footnote 60

This example also shows how the captain respected the rule of at least ¾ English men of the Navigation Act at the lowest possible limit – 16 of 22 would not have been enough – as foreigners were cheaper. The ⅔ rule of the sea-pass issuing instructions was overridden here. The difference between those several quotas remained. It also shows that quite often the ships left England with fewer than two men for each of at least sixteen guns, which would be here thirty-six men. If they entered like that London on the way back, they would have to pay the one percent duty of the Act of Frauds. Often, they hired still more men within the Mediterranean.Footnote 61 The problem of how to handle “English ships” without passes remained, as is evident already from the later treaties.Footnote 62 As those early eighteenth-century passes contain the destination of the ship, so did also the registers restarted in 1730, obeying a different notation system, following an order of December 18, 1729: a first destination (“Whither bound” directly from the place the pass is received at) and a second destination (“Whither bound from thence”) was noted in two columns. So, passes were now issued to ships for instance “of London,” currently lying in the “Thames,” heading for New England by passing the Straights of Gibraltar and then back to Lisbon. Or first to “Lisbon, New England,” counted as one first destination, and then to the West Indies. All ships now enrolled in the London Admiralty registers had to be currently anchoring at a port of the British Isles.Footnote 63

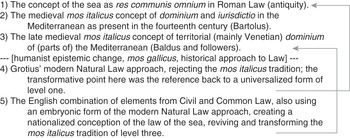

Figure 1.1 and Figure 1.2 Two English Sea-Passes, left of 1717 without the upper part, on the right of 1719 with the upper part still attached (AN MAR B7/473). On the left are visible the two blue 6 pence duty stamps for issuing, which are not the bond to be left, the stamp of the Admiralty on the left and the number of the passport (Nr. 17675) as it was registered in the passport register. The only printed matter is the ship and title in the wreath of leaves; but the text below is nevertheless a form already written by the officers with blanks left to be filled in (names of ship and captain, dates etc.).

One may ask why the northern nations relied on the strongly formalized sea-pass system, while the French congé documents remained far less developed. The higher interpenetration of Atlantic and Mediterranean trade reveals a reason for this. As the Atlantic trade grew, it was first not necessary to demand a sea-pass from the Admiralty in London when coming from the plantations; a certificate from the respective governor or his representatives was considered sufficientFootnote 64. This, however, was a simple document written in English like a French congé without the haptic element of two parts that had to fit together. A ship, coming from there “and trading to Portugal, the Canaries, Guinea and the Indies” without any such pass would be taken by the Algerians despite its clear appearance of British property.Footnote 65 While the Romance languages were strongly present among the Barbary corsairs – themselves often renegades from Mediterranean countries – and as their lingua franca was itself a fluid mix of Castellan, Catalan, Italian and Arabic elements,Footnote 66 documents from Mediterranean countries were more likely to be understood at sea, even if illiteracy was a problem. English was not a frequently spoken or read language on the North African shore. Consul Wisham recommended, in 1714, the issuance of real Mediterranean sea-passes and not only the said certificate to ocean traders coming from the Americas, Asia and Africa, because the Barbary corsairs “being not only entirely ignorant of the English Tongue, but even of the Characters of any Christian Language, can make no Judgment whether such Certificates are true or falses, and that the only mean whereby they can know <a> ship belonging to Her Majestys subject is by comparing the Indent of Passes with the Passes themselves.”Footnote 67

The Admiralty and customs officers in British ports not only sought to determine the “Englishness” of the ships and their men, the administration also ensured itself by the typical early modern “last step” of assurance, the ship master’s oath. A promise under oath that the ship was English-built, belonged to the English, and that the necessary amount of men were English, served as a convenient capstone for the construction of the account books’ correctness. To a certain extent, it also replaced reality through its sworn statement. If it later proved to be wrong, the administration could always blame the master, but for the pass registers, the exact number of outgoing English and foreign men was saved. According to those rules, English nationalizing was successful. Nearly all importing and exporting into and from the Mediterranean was conducted by English ships as early as 1615. The English had lobbied with energy against any plan by Italian firms to be established in London.Footnote 68 The nationalizing of the ships themselves took longer. Between 1654 and 1675, the share of foreign-built ships was between a third and the half of all ships leaving English ports, a proportion that fell from the 1680s to less than 10 percent.Footnote 69 This indicates that the naturalization of ships – or, “making them free” – was of high importance; a large number of ships taken from the Dutch was “freed” in 1668/70.

The elite in Algiers and Tunis, the Dey, Bey, the milice and the Divan, was well aware of the European legislationFootnote 70 and knew what the treaties stipulated. When the English government communicated the new rulesFootnote 71 for granting sea-passes to its consul in Algiers, Samuel Martin, in 1675, he transmitted this information to the Dey, provoking discussion in the Divan. The new Algerian ruler Bobba Hassan complained about the “many forraine shipps sayling under English Collours” but admitted that this could very probably not have been by permission of the English themselves as it was not in their own interest as the “true [sc. English] subiects found the lesse Employment for their shipping.”Footnote 72 This was a time when the French were attacking their Northern European rivals – Hamburg, the Dutch – which rendered the British flag especially attractive. Many ships used it even if many of their sailors and even their captains were not English.Footnote 73 Such extensive use of a flag formally protected by the treaty induced the corsairs to bring ships into the Algerian harbor, and to distinguish there by closer scrutiny between “English” and “non-English” passengers. Applying in 1677 the clause of the 1662 treaty requiring a “major part of the ship’s company” to be English, they classified a ship like the English-built Susannah sailing from Livorno to Palermo with its English captain Walther as not English “because his number of passengers, & strangers exceeded the number of the English Men.”Footnote 74 The rule that ¾ of the men on board had to be English was apparently quite successfully implemented on vessels arriving in and departing from England. But English ships within the Mediterranean, such as most of the Italian merchants based in Livorno, could and did depart more easily from those rules.Footnote 75

The French were affected by the phenomenon of the borrowed or abused flag far more than the British. Before a ship left Marseille, it had to be checked by the commis of the lieutenant de la Marine. At least after 1681, there should have been a rôle d’équipage, a list of all men on board. The French counterpart to the sea-pass was the congé for the ship that was likewise issued against a certain payment according to a fixed tariff. The congé could, in theory, only be issued if two thirds of the men on board were French “currently resident in France.”Footnote 76 From 1696, however, because of the system’s frequent abuse by foreigners, a different congé form was distributed with the inscription “Etranger.”Footnote 77 The higher frequency of flag abuse was due to several causes: the partial free-port status of Marseille, the effective nationalization of the Levant import and export shipping by the English and their Levant Company’s monopoly, and the more fuzzy French legislation developing in a back-and-forth manner.Footnote 78 A 1671 order prevented French merchants and ship owners from lending their name to strangers (“prêter le nom”), an old practice of foreigners using the “Frenchness” of a Marseille merchant for their own purposes. Immigrants to cities often tried to use the names and the signs of the privileged burghers and guild members. This forbidden practice was also called “prêter les noms ou marques.”Footnote 79 Between 1671 (Ordinance of May 20) and 1727, this practice, usually exercised by way of counterfeit contracts, was sometimes defended absolutely, sometimes it was allowed again partially as between 1684 and 1717. Other regulations concerned restrictions of naturalization standards. Foreigners who had been granted a letter of naturalization but who had not really abandoned their domicile in their former homeland were deprived of the privilege of naturalization, a rule designed foremost against Genoese merchants who had apparently established a practice of dual nationality and residence, and enjoyed the privileges of flag use, protection and tax reductions of both places, and the ability to flexibly choose the best conditions for each given freight and voyage (royal declarations of August 21, 1718; February 1720).Footnote 80 The 1727 declaration linked rules concerning the property of ships and the use of flags with very specific regulations about how to keep a register of the ship lists (“rooles d’equipages”) containing the names and nationalities of all men on board, from the captain to the passengers and every sailor.Footnote 81

The ways to undermine the rules relating to the distribution of congés were apparently much more multiform and frequently applied in the French case. Deviation from the ideal started right in Marseille, while for the English, it seems to have been more a question of difference between the London homeport and shipping realities in the Mediterranean.

Nationality in the Practice of Shipping and Slave Ransoming

This steady processing of “the national” through the observation and the breaking of rules, and through communication about them can be shown through several examples from the Mediterranean.

Regarding the English, it was not uncommon to find foreign-built ships, belonging to strangers with only the captain and a few English men using the English “Bandero.” For example, the treasurer of the Bey of Tunis, a Jew, wanted to use a non-English built ship with only three English men on board. Old sea-passes were usedFootnote 82 which had not been returned to the Admiralty with “scratch’t names & put others in their stead.”Footnote 83 Sometimes a consul issued a pass to merchants to let them deliver their goods to a North African city, and when departing, because they had no passes, these mariners obtained protection from privateers, either European or Maltese, or even the Algerians.Footnote 84

New subjects of the British king were not always included under protection granted by peace treaties without some difficulty. The inhabitants of Gibraltar, Port Mahoney and Minorca, for example did not appear to be very “English” to the corsairs.Footnote 85 They obviously feared that those Catalan-speaking British subjects would be hardly recognizable and “that the Mayorkeens Cattalans and other Spaniards may hereafter clandestinately make use and navigate under Brittish Colours” if the door was opened once to such an un-northern Englishness. The consul proposed himself as the authority to “distinguish who are his Majestys right subjects and who are not” by inspecting Mediterranean sea-passes in question.Footnote 86 If ships came in now from Gibraltar to Tunis, it could be a matter of life or death if the consul and other representatives of the English nation, requested by the Bey, accepted the papers presented to them.Footnote 87 Could an English Mediterranean pass from Gibraltar protect a Catalan tartan and could a bill of health produced there testify to the health of the men on board, or neither of these things?Footnote 88 Ships which were even less clearly British – a Genoese captain coming from Gibraltar leaving a ship without men and protection anchored offshore Oran – could fall into the hands of corsairs if the English men were not on board and the British embarkation pass from Gibraltar was with the crew and captain at a tavern ashore.Footnote 89 While here Catalan-speaking British subjects and ships, or enslaved German-speaking subjects of the British Crown from Hanover, such as one Albrecht Wilhelm ForstmeierFootnote 90 had to be protected, English speaking Irish Catholics naturalized in Spain could likewise complicate the usual patterns of recognition.Footnote 91 Far away in Northern Europe, those Mediterranean affairs with the corsair economy could trigger merchant migration and therefore the fluctuation and repartition of nationalities, as traders moved from a neighboring territory some miles across a border to become inhabitants and later naturalized subjects of a British dominion, such as Hanover, in order to obtain access to British sea-passes.Footnote 92

The British protection of a ship could also be obtained by paying a consulage duty to the Levant Company in the Mediterranean. In those cases, completely “un-British” ships sailed under that flag, and if some problem occurred, the “national” was affected as the consul of the place was typically involved and had to resolve not only a technical problem, but also defend the reputation of the flag. A Greek, George Aptall, a former member of the Oxford Greek College,Footnote 93 who apparently pursued the career of ship captain, sailed with his ship from Alexandria to the North African ports “with goods belonging to Turks and with 30 Turkish passengers,” but Aptall made a stop in Crete, murdered six of the Turks and sailed away with their goods. As the consulage was paid to the vice-consul of Alexandria, the Turks tried to get recompense from the English Nation, obviously thinking of the British protection as something like insurance.Footnote 94 Cases like this put the consul and “the nation” in serious conflict against the Ottoman authorities. A Turk of Smyrna who had chartered a pollacca of a certain Mariano Julia who enjoyed British protection as being from Port Mahoney, while of quite un-northern appearance (with a “poor old Turk, & a negro girl”), as the consul felt obliged to remark, dissolved his contract because of the French threat. In October 1741, a ship under British protection sailed from Malta to Tripoli with “Ninety Moors, men, and Women, all Pelgrimes who were coming from Alexandria with a Sweedish ship to Malta.” The French took the ship and enslaved the passengers, putting some on the galleys in Toulon. In response, the pasha of Tripoli now appealed to the English, as the ship was under their protection.Footnote 95 The freeing of enslaved Algerians, passengers of a ship under British protection taken by a Spanish cruiser, could become a state affair that did not just involve the captains and the consul in Algiers, but the Dey, and in London the Lord Justice, the Secretary of State, as well as the British ambassador to the Spanish Court in 1722/23.Footnote 96

It is generally argued that the Europeans had their different ransoming institutions while the Moroccans and the Maghreb had not.Footnote 97 The cargo trade and the lending of protection to foreign ships, as in these cases, could produce paradoxical situations where the Muslims gained access to that infrastructure of the consular and diplomatic system, pitting Europeans against Europeans.

Despite and because of the 20 percent duty, and because of the steadily growing importance of the French market, the French flag was highly attractive in the Mediterranean.Footnote 98 Aside from the more complex naturalization process, the already mentioned counterfeit contracts were the most frequently used way. That those contracts were simulated was obvious to the locals in Marseille, cognizant that the modest fortunes of a given master could not have permitted him to really buy an expensive ship.Footnote 99 In reality, the ship master acted as employee of a foreign merchant, but before the French port administration, he presented himself as owner and, being himself of Marseille and falling under the other rules of the royal ordinances, he could obtain the congé of the Admiralty and the right to use the French flag for a ship that was completely foreign in economic terms. There were other ways too; the simplest was just to take several flags on the ship. This meant there were English ships with French and Spanish flags on board, and a ship with only Irish men on board sailing under English flag, but with passports of the French Admiralty in Brest, meaning Irish Catholics switching between Britishness and French protection.Footnote 100

A case in some way comparable with the English intervention for captured Muslims occurred in 1717 when Algerians took a ship commanded by a French captain with 119 Spanish passengers, sailing from Barcelona to Valencia, which, because of its French passport, the French consul in Algiers had taken under his protection. The consul ended up hosting the Spanish for three years in his own house, because the Algerians were only willing to free them in exchange for 130 “Turks and Moores” taken in 1716 by the Sicilians of Syracuse – then ruled by Savoy after the treaty of Utrecht – who had likewise traveled on a ship with a French captain. This put the French in the position of an “arbiter” between enemies, but the whole affair was perceived as causing dishonor to the French flag. While on the one hand the French could flatter themselves as having something like precedence and hierarchical dominant rule among the Europeans and even over the corsairs, they were also challenged to prove the efficiency of their protection.Footnote 101

The deviations from the French norms about who was allowed to sail with the French flag were perceived by contemporaries as a mass phenomenon instead of single cases. This is also true for how the French perceived the matter themselves. During the regulatory period of the regency from 1715 to 1717, the intendant des galères Pierre Arnoul, and the Chambre de Commerce unsystematically gathered data about the abuse of the French flag at sea through the interrogation of incoming sea captains. Five captains gave accounts of many ships from St. Remo, Naples, Malta, Sicily, Genoa and Messina that they had encountered, providing incomplete lists of some thirty or forty ships whose names and captains they remembered. All had flown the French flag, but often it was at best the captain alone who had been French or naturalized, while all the men on board had not been French.Footnote 102 Similar notes, gathered less systematically, are to be found in reports of how the Deys and Beys of Algiers, Tunis and Tripoli complained about counterfeit Frenchness.Footnote 103 Sometimes massive fleets, as in 1699 some 200 ships, passed the North African coast with French flags and the Algerians let them pass without examining them. But impossibly, the consul suggested, all of those 200 ships were really French.Footnote 104 The use of the French flag by ships that had in fact never visited a French port evidently occurred much more often than with other European nations from at least the 1680s, however.

Ransoming communication was, from the perspective of the epistemic of mercantilist political economy, a secondary phenomenon. The national belonging within captivity and ransoming correspondence was distinctly connected more to the state level than the merchant economy. Literature on captivity and ransoming is expanding, and sometimes the issue of identifying captives of one’s own nation has been addressed explicitly.Footnote 105 The impression gained from what the archival records reveal and what scholars have discovered until now is that the sources do tell a great deal about the need to identify the nation of captives and about how eager both consuls and corsairs were to do so. Nonetheless, there is little evidence about how such identifications were conducted in early modern times. Seldom do we have consular correspondence or the ransoming orders really sent to a captive’s country of origin, requesting entries in the parish records. For those that do exist, it remains unclear how that entry could have helped to confirm anything other than that there was an entry for a person of that name in that parish. The application of that knowledge gained for the captive claiming to be that person hundreds of miles away in North Africa still remained, in the end, arbitrary. Some slave lists (infrequently) contain rudimentary forms of captives’ physical descriptions,Footnote 106 but they usually only offer lists of names with the place of origin.Footnote 107 In all likelihood on shore, the language spoken by the captive and who he claimed to be, if believed and supported by the consul, was usually the only communication that reified a nationality, as many passengers and sailors possessed no passports or letter of conduct.Footnote 108 Usually corsairs, as well as Europeans, simply referred in writings to, for instance, “5 French and 7 Dutch slaves” or something similar. Research on early modern identification processes within the proto-national states has shown how complex and unclear the standardization of descriptions and modern record keeping was in times before photography.Footnote 109 Matters were still more complicated in a zone of constant travel and assimilation among merchants, sailors and passengers such as the Mediterranean shores and at such great distances from the metropole. Boubaker has underlined the high “importance attributed to national belonging” by religious as well as state institutions and that “mostly, both sides kn[e]w the identities of the persons,”Footnote 110 and this is true. Yet one must add that we do not know much about how that past conviction “to know” was achieved and if we, according to current measures of what might be deemed knowledge about personal identities and nationality, would call that “knowing.”Footnote 111

Where Does the Nation Start and Stop? Irritations and Reflexivity

It is evident from what has been shown that the mercantilist communication created the paradox of an ongoing query for the nation and for national attributions, but that it often ended up in an awareness of ignorance. Most interesting in this context are those testimonies of experts and administrators of the regulations to be executed that betray a reflexive analysis of those paradoxes and of the functioning of the norms themselves. Some of those observations show that, to some extent, what has been widely considered a major insight of the twentieth century – the constructivity of nations, or their status as imaginations, as that of other community discourses – was already available to the constructors themselves.

In 1748, the chaplain to the factory in Algiers, Thomas Bolton, wrote a memorandum to the Secretary of State, the Duke of Bedford, in which he explained the attractiveness of the British flag. He conceived of all Barbary/European intercourse in the Mediterranean as essentially a story of imitation of the initial English war/treaty solution established in 1662 after Admiral Blake’s 1647 victory, even that of Ludovician France. Bolton attributed the rise of the Swedish, Danish and Hansa cities during the first half of the eighteenth century to the “inactive reign” of the former Dey who died in 1745.Footnote 112 The result was that all of a sudden the smaller neutral powers and Italians became the preferred carriers of trade, even by English merchants themselves.Footnote 113 Evidently then, and not without surprise, there was a precise awareness about the causalities between flag use in the carrying trade, war, peace and the opportunities of neutrality. The reflections of Robert White from two years later are even more sophisticated: The Act of Frauds of 1662 included explicitly under the term “English men” all the king’s subjects from England, Ireland and the colonies.Footnote 114 The 1660 Navigation Act and the administrative practice similarly understood as “British-built Ships” all “Ships built in Great Britain, Ireland, Guernsey, Jersey, or the British Plantations in Asia, Africa, or America.”Footnote 115 But during the last Jacobite upheavals in Britain and their repercussions on the shores of the Mediterranean – where fear of Jacobite conspiracies among the English nation and employees of the Levant Company was frequently mentioned before and around 1750 –,Footnote 116 Imperial administrators reflected upon the restrictions of that definition of “English.” White creatively interpreted the renewed treaty clauses with Algiers of August 1700 in retrospect, trying to prove that neither of the contracting parties, at that time before the Act of Union between England and Scotland that formed Great Britain in 1707, could have intended to include “Scotland, Ireland, or any of His Majestys other Dominions” under the term “England.”Footnote 117 Nor could the term “British Ships” reasonably have been thought to “cover or imply all Country Ships belonging to His Majestys Dominion.” Finally, White deconstructed the very core of the processes of identification and national attribution, the moment of matching the upper and the lower parts of the sea-pass:

Besides, this whole article seems to render the Security of Passes very uncertain and precarious, Because the vague term, Fit, which is the Ruling Term in the Article, may admit of many Different Meanings. It may be understood for the Scollops fitting, for the Lines fitting, for the Length, Breadth and Thickness of the Pass fitting, It may be constructed to mean One or all of these, or any thing else.Footnote 118

Beyond the particular situation – five ships had been brought into Algiers because the scalloped Passes did not correspond with the corsairs’ counterpart – the reflections show an awareness of the somewhat unreal moment of testing nationality, how the fitting (or not) together of some pieces of parchment was the code for being British/not-British. It was the code for freedom/captivity, and even for life/death.

White’s reasoning, obviously based in his training in Common Law legal language analysis, was dominated by the aim of delegitimizing the existing treaties with respect to a precise political situation. But it shows nevertheless an astonishing amount of awareness of the problem of “how to know the nation.” It even shows the availability of relativist thought about the constructedness of nationhood as it was defined by the “fitting/non-fitting” of two pieces of parchment. If, like White, one starts to reflect on definitions, they become fluid. The fifty-year distance since the Union had added an additional amount of relativity to that; it made the past political situation unsuitable to dictate the present. This magic moment of the nationalizing “fitting” of sea-passes was deconstructed like rationalist reformed theologians were trained to deconstruct the mystical moment of transubstantiation. While one analyzes today sometimes the past discourses of belonging or not to a nation in a Schmittian way as secularized forms of belonging or not to the corpus mysticum Christi,Footnote 119 proto-constructivist thoughts about national communion building were apparently possible just by reflecting on the crude materiality of identification processes such as pass matching.

For the French, one can find similar forms of reflexivity in mémoires concerning the functioning of the whole Mediterranean seafaring and trading system between 1715 and the 1730s in response to the abuses of the flag, mostly by help of the counterfeit contracts. In those cases, once issued, captains used the admiral’s congé for several years and the port administrators tolerated all this when the ships returned to a French port. As a result, according to a memorialist in 1715, foreign ships had effortlessly taken over shipping from the French, but still under French flag, as the “real” French ships now remained without work in their home ports. This also created something like a low-cost market for French sailors who were present in foreign port cities to be hired to fulfill, at least partially, the French equipment rules. Paradoxically, the French realized that after fifty years of Colbertian legislation, French protectionism – at least if run too laxly – could create economic exiguity for the French and profits for foreign (Italian) merchants.Footnote 120

Only fifteen years later, the situation changed once again. With pride, an anonymous 1731 memorialist of the Chambre de commerce remembered that they had flattered themselves by the French flag’s attractiveness and its “high reputation with foreigners” until that date, while Dutch and English ships in the Mediterranean could find almost no tonnage besides their own commerce for decades.Footnote 121 Now, the peace had changed the situation. Competition had risen and the French now risked losing their share of the carrying trade market. At that point, this memorialist warned about the ill effects that would result from severe protection that followed too rigorously the “maximes d’Etat” instead of an economic rationale. He therefore openly recommended what seems to have even been the usual practice for a long time, a somewhat laissez-faire enforcement of laws that would re-allow foreigners to take up to a third of the stake in the property of French shipping as had been the rule in the glorious times of Louis XIV. In so doing, he justifiably criticized the decision taken by the Régence administration in 1716/17 as being too rigid and perhaps too informed by state theory, in an attempt to convince Louis XV to return to the political economics of his great-grandfather. Indeed, Maurepas responded to Lebret at the end of January 1732 by accepting the necessity to tolerate the abuse of the flag “by not always observing strictly the 1727 declaration” in order to not lose foreigners as important subcontractors of French navigation. The “inclination to our nation,” he declared, was of high importance for France. If the advantages of the (ab)use of the French flag by the foreigners had been “more than reciprocal,” the nation would have profited infinitely from it.Footnote 122

The protectionist perspective on the second level of Mediterranean economics, piracy, in 1715 was that the corsairs were well acquainted with the rules requiring a ship to be manned by at least ⅔ Frenchmen. If they captured one of those counterfeit French ships with old passes and nearly no Frenchmen on board, they normally enslaved the whole crew to the great dishonor of the French nation. However, if the waters of the Mediterranean were plied only by ships flying the French flag, the corsairs would have had, in the end, no possible target for their main business, piracy. This would force them to resume attacks against French ships. The complete dominance of the French flag was therefore dysfunctional within the given system.Footnote 123

It seems that the 1715 “white flag overflow” argument was not the winning one. After the Maurepas administration had adopted the policy of tolerant enforcement in the 1730s and following a favorable capitulation with the Ottomans in 1740, the French had found their balance.Footnote 124

What is interesting here is how, within fifteen years, the arguments could completely change direction. It is remarkable how the French realized and reflected upon the economic functions and dysfunctionalities of their own regulations, how they recognized a quite simple everyday practice of simulating Frenchness. While naturalization procedures and belonging to a nation were, on the one hand, so restrictive and bound to blood and soil, as the research of Sahlins and Dubost has shown, the undercover use of nationality as a mere sign and currency within the Mediterranean shipping context betrays the other side of the same coin: the national became an element of steady processing from the 1660s, and because of that, its status as an attribute and a sign, that is, its constructedness became likewise visible. Nationality became objectified as the content of specified (non-)knowledge, but objectifying it also meant exposing its partial arbitrariness.

Those moments of high reflexivity concerning the sign status of the national show that, at the same time as the central mercantilist distinction of what was internal or external was sharpening, it also became underdetermined. Terminologically speaking, this was no retreat to the prior state of nescience about the “national,” no return to the more fluid and much less specified situation before the 1660s. It was rather, in a spiraling way, a new form of reflexive awareness about the usability of the national created by undermining the valid norms or by the skilled use of them – all this long before the modern nineteenth-century heydays of nationalism. Just as how the post-Reformation plurality of confessions and the micropractices of playing and use of these confessional boundaries in a pluralizing manner were not the same phenomena as inter-religious exchange in the Middle Ages, the perforation and deaggregation of the specified national was different from the earlier state of unconscious ignorance about it.

A Comparative Look at the Medieval Conditions

To test the historical specificity and the new character of the 1660s regulations, it will be helpful to have a comparative look at earlier situations in the Mediterranean. As the sixteenth century was, from roughly 1492 (the Christian conquest of Granada) to 1574 (the Ottoman reconquest of Tunis) a period of unsettled circumstances along the North African coast, it is more enlightening to consider the late medieval period, before the Ottomanization of the region. Many caveats of “incomparability” may be brought forward, but on the other hand, the continuities of the corsair activities of the North African cities/kingdoms are striking.Footnote 125 The Berber kingdoms of Fez, Tremecén (with Algiers, Oran), Tunis (Bugía), Granada (Almería) and their corsair attacks on European – foremost Aragonese – merchant shipping form the direct precursors of the early modern situation. The sixteenth-century Ottomanization meant mostly the implantation of a Janissary elite in the city states which took over much of the Berber seafaring and corsairing traditions.

The different ways of obtaining ransom from Berber captivity in late medieval times were (a) ransoming through individual friends, merchants, families,Footnote 126 (b) ransoming through the religious orders, above all the Trinitarians (founded in 1198) and the Mercedarians (founded in 1218), but also through the military orders, (c) ransoming by help of corporative and municipal institutions, (d) ransoming through a monarch’s direct diplomatic intervention. In Spain, the alfaqueques had been professional ransoming mediators acting on behalf of the crown or of municipalities since the thirteenth century, but they mostly operated on the inner Spanish Christian-Muslim territorial border.Footnote 127 Trinitarians and Mercedarians were late order foundations linked to the challenges of the crusades, and their only reason for existence in terms of competing with the established military orders was their specialization in ransoming captives.Footnote 128 They were not very active in either the Holy Land or the Eastern Mediterranean, and if so, more as hospitallers than as ransomers.Footnote 129 Despite the early foundation of the Trinitarians in Marseille, which is probably attributable to specific Provençal interests,Footnote 130 their activity in the late medieval period is scarcely documented in either France or Genoa.Footnote 131 Consequently, following the spread of their monasteries in Spain, the Trinitarians formed, with the Mercedarians, whose origin and center had been in Aragón, a rather regionalized religious order concentrated on the problems of Aragón/Castellan/Murcia connections with the inner Spanish Arabic and the North African Berber corsair threat.Footnote 132 Even in this region of their main activity, we do not possess much certain archival evidence of their ransoming activities, even though largely retrospective, hagiographic and advertising publications of the orders claim that they freed several thousands of captives.Footnote 133 The non-hagiographic documents that we possess from the fourteenth century show that the ransomed persons were in fact all from the dominions of the Aragonese crown in the Mediterranean, from Spain, Sicily and Sardinia.Footnote 134 But none of the Trinitarian or Mercedarian sources spoke of their task other than as freeing “Christian captives” (not “Aragonese captives”).Footnote 135 Municipal institutions are a different matter.Footnote 136 The most famous of these is the Entidad Valenciana en pro de los cautivos, founded in 1323 and active until 1539, which organized the charitable collections from a city’s parishes for ransom in the form of efficient city-state bureaucracy. This became a hybrid between a municipal duty or tax and traditional church collection. Here, the money was reserved only for Christians of Valencia. Only if there were no more Valencian captives could the money be used for Christians from the kingdom of Valencia, preferably from the city’s neighborhood. Here a tiny proto-national element was evident, but in practice it was purely municipal.Footnote 137 Diplomatic negotiations between the Aragonese kings and the Muslim kingdoms over peace treaties could seem most similar to early modern realities. The cedulae, the royal instructions to Aragonese ambassadors and the peace treaties themselves, show how the kings focused on the freeing of subjects from their territory as an act of the lord’s duty of protection.Footnote 138 The normative form of the peace treaties is very different from the early modern treaties between the Barbary and the European states. The Aragonese treaties were formulated like conclusions of a peace following war. The liberation of captives was conceived in terms approximating the prompt exchange of captured warriors after a decisive battle. There were no precise regulations of future shipping or other exchanges, of ship control, and no pass system was inaugurated. The liberation of captives in those peace negotiations was not accomplished via ransoming either. Only the fact that the Aragonese envoys negotiated the number of freed captives in exchange for a proportional number of years of peace shows that both sides acknowledged a prolonged period of regular corsairing and the taking of captives instead of a situation of discrete war and enduring periods of peace.Footnote 139 The selectivity of freeing and protecting just their subjects was therefore not born out of the context of inner-European and inner-Christian economic competition and the captivity market.

With good reason medievalists stress that the practice of mercantilism has its roots not in seventeenth-century England or France, but in twelfth- or thirteenth-century protectionist trade policies, for which not just Aragón but also the French kingdom and the Italian imperial republics Venice and Genoa were spearheads of development.Footnote 140 Aragón’s competition with late medieval Italian merchants is perhaps the most profiled example and anti-Italian Aragonese legislation, culminating in King Martin’s edict of January 15, 1401 can be seen in perfect continuity with the policies and practice of trade of the then leading seventeenth-century states.Footnote 141 Yet the lack of competitive proto-national semantics within ransoming correspondence suggests that the late medieval economic system of the Mediterranean as a whole cannot be understood as an already fully developed two-level system of international trade competition on the one hand and parasitic corsair activity on the other. The smaller naval capacities of both sides meant that exchange between them was more regionalized, and that inter-Christian competition was far less state-defined in the Mediterranean as a whole and in interaction with the Levant and North Africa in particular.Footnote 142 If Aragonese politics in North Africa has been characterized largely as an imperial economic enterprise,Footnote 143 it had not been so in competition with European powers at this point. If, too, Aragonese ships were competing with Castellans and Italians and, from the fifteenth century, with the Portuguese, this competition was not linked in a triangular way to the confrontation with the Berber kingdoms as was the two-level system of seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

Even in quite similar structural situations and with actors such as Aragón, perhaps the “most modern” of all medieval kingdoms, one still cannot detect real genealogical precursors for the epistemic situation of the seventeenth century. National belonging remained, in medieval times, more in a state of nescience. If the processing of “the national” in all politico-economic communication did not first begin with the standards of the 1660s, this still was a moment of unprecedented enforcement wherefore it can be taken as an epochal turning point.

The Political Arithmetic of the Unknown: The French Nation

Attempts to shape the reified result of the investigation processes into national attributes were a final matter in which ignorance and specification of the unknown national played a crucial role in the seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Mediterranean imperial administration. At first, this concerned the nation in its narrower sense, which derived from the medieval concept of naming a group from a given region or country within a plural, “multinational” context a natio: the nationes of a university, of a military order or, as here, of merchant colonies. By and large this only applied to the French side in our study as there were virtually no traces of the state dirigist organization of the “English nation.”

There are several thorough studies of different French “nations” in the narrower sense for Tripoli in Syria,Footnote 144 Tunis,Footnote 145 AleppoFootnote 146 and Constantinople,Footnote 147 but there is no study of how the Paris/Versailles center tried to organize the nations in the échelles as a whole.

The decisive period of the French state’s empirical investigation into the échelles and of its major regulatory efforts was between 1685 and 1730. Since the late seventeenth century, the ambassador in Constantinople and the consuls regularly reported to the Chambre de commerce in Marseille and also to Versailles about the number and the character of the merchants in each place.Footnote 148 Sometimes a general numeric overview of all the French in the Levant was elaborated, but there was no established administrative practice of annually counting all French subjects.Footnote 149 But sometimes, as in 1732, the French Ministry tried to obtain a current overview “of all the Frenchmen living in the échelles.” This was linked to the decision to send certificates of residence to all those who had not yet acquired one if they matched the criteria of bon-conduit.Footnote 150 A constant perception of deception, of not knowing the exact realities is apparent and a continual desire for central control was notable.Footnote 151 Many unforeseen travelers, “vagabonds,” “français oisifs” – as they were called in the sources – were detected.Footnote 152