Book contents

- French Visual Culture and the Making of Medieval Theater

- French Visual Culture and the Making of Medieval Theater

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Book part

- Introduction

- Chapter One “Vocamus personagias”

- Chapter Two “Ouvrez vos yeux et regardez”

- Chapter Three “Faire semblant”

- Chapter Four “Cy s’ensuit le mystère”

- Chapter Five “C’était qu’un jeu industrieux”

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

- References

Bibliography

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 18 December 2015

- French Visual Culture and the Making of Medieval Theater

- French Visual Culture and the Making of Medieval Theater

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Book part

- Introduction

- Chapter One “Vocamus personagias”

- Chapter Two “Ouvrez vos yeux et regardez”

- Chapter Three “Faire semblant”

- Chapter Four “Cy s’ensuit le mystère”

- Chapter Five “C’était qu’un jeu industrieux”

- Conclusion

- Notes

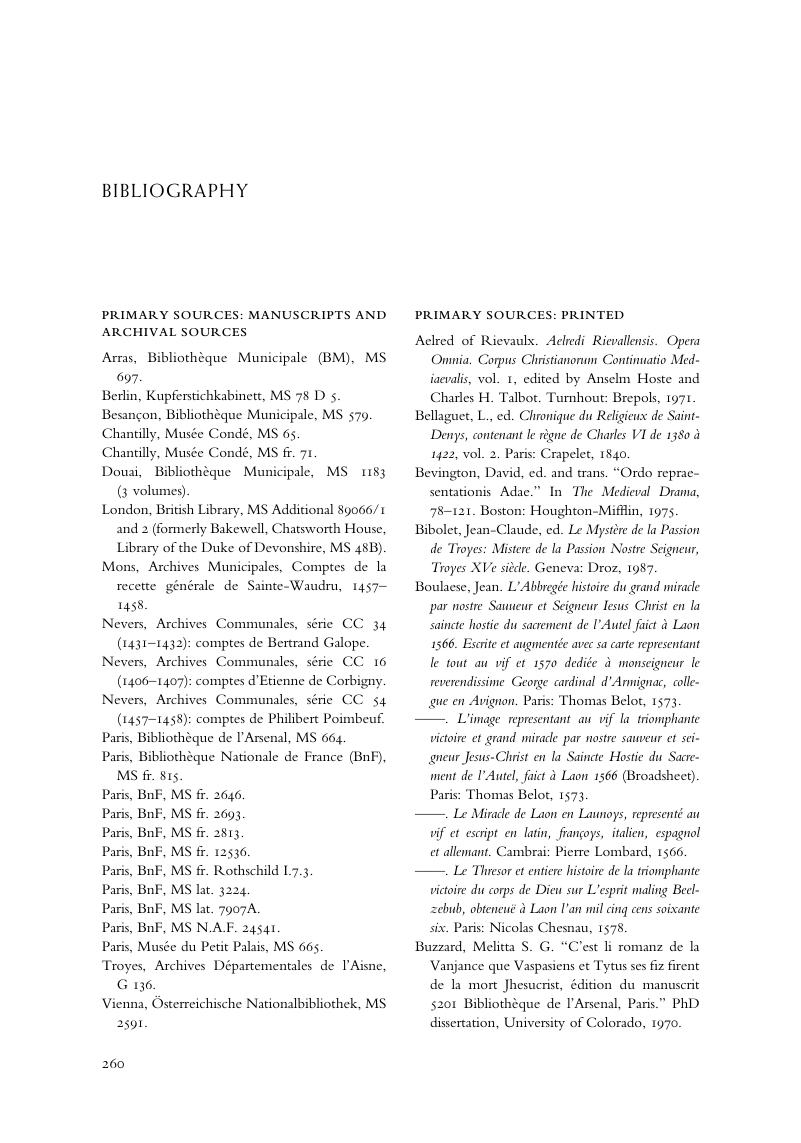

- Bibliography

- Index

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- French Visual Culture and the Making of Medieval Theater , pp. 260 - 278Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2015