1 - Tools of the Puncture: Skin, Knife, Bone, Hand

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 21 May 2021

Summary

[…] a descrete leche schal openly knowen

þe tortuouse depnesse of his enserchinge.

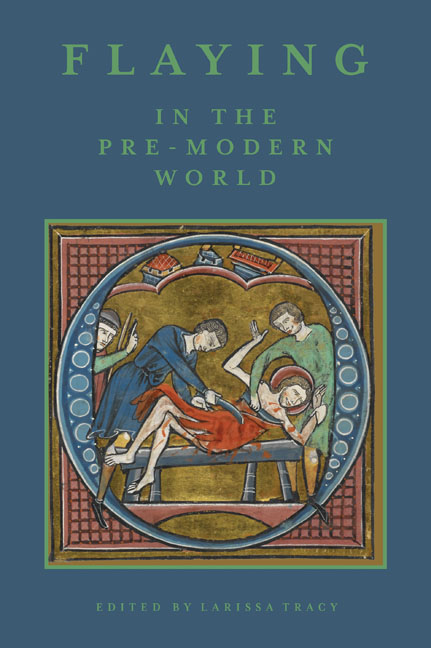

A HAIRLESS figure stands at the centre of a manuscript illumination, his curved body delicately tinted pink and apparently naked (Fig. 1.1). He seems to be looking vacantly outwards, staring into the empty space immediately to his left. Yet, on closer inspection, this cannot be; he has no eyes or eyelids, only empty sockets. In fact, his body sports no outer layer at all: His skin is folded in two like a piece of stiff fabric, slung over a long stick he carries at his shoulder. Amongst the flaps and folds, his arms and legs are still distinguishable by their intact hands and feet, as is the body's once-full head of hair which spirals out in strange black weaves from a central corona-like scalp.

Despite the singular and static depiction in front of a traditional checker-work background, this is not a devotional image from a religious text. It certainly resembles depictions of St Bartholomew, rendered unflinching despite his absent skin through a sense of anaesthetizing spirituality, but this is not the saint inventively presenting his pelt on a pole. Neither is this a figure from more mythic or historical sources: the corrupt Persian judge Sisamnes, for example, whom Gerard David depicts so vividly in a 1498 diptych, flayed alive with his skin draped across his chair of judgement. Nor is this figure intended as a more playful marginal image, parodying or punning on the grotesque. Unlike the two miniature wide-eyed rabbits who flay a bound man in the bas-de-page of the Metz Pontifical, this skinned man is central to his manuscript context, spanning with bold prominence an entire column of text. Instead, this image stems from a sphere of visual culture that provides an important counterpoint to the punitive and saintly narratives of skin removal: the emergent medieval discipline of surgery. Rather than exclusively embodying flaying's violent aspects – an idea that chapters later in this collection will go on to explore – this skinless man was used instead for instruction in healing. This is a flayed figure of repair, rather than removal.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Flaying in the Pre-Modern WorldPractice and Representation, pp. 20 - 50Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2017