Book contents

- Half title page

- Ideas in Context

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Book part

- Introduction

- Chapter I The untimely generation

- Chapter II The problem of politics in Arendt’s and Strauss’s early writings

- Chapter III History and political understanding: An ambivalent symbiosis

- Chapter IV Liberalism and modernity: Rethinking the question of the “proud”

- Chapter V Retrieving the problem oftheoriaandpraxis: The antagonisms

- Epilogue

- Bibliography

- Index

- Ideas in Context

- References

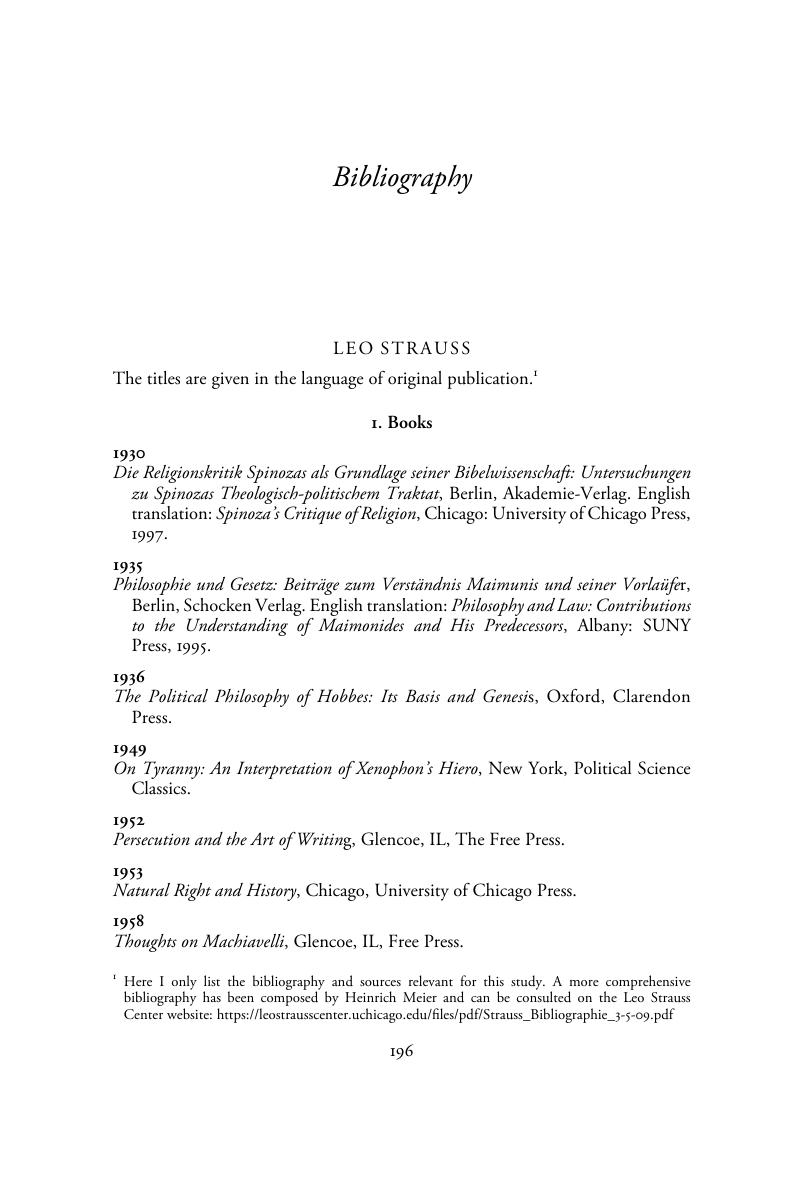

Bibliography

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 March 2015

- Half title page

- Ideas in Context

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Book part

- Introduction

- Chapter I The untimely generation

- Chapter II The problem of politics in Arendt’s and Strauss’s early writings

- Chapter III History and political understanding: An ambivalent symbiosis

- Chapter IV Liberalism and modernity: Rethinking the question of the “proud”

- Chapter V Retrieving the problem oftheoriaandpraxis: The antagonisms

- Epilogue

- Bibliography

- Index

- Ideas in Context

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- The Crisis of German HistoricismThe Early Political Thought of Hannah Arendt and Leo Strauss, pp. 196 - 220Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2015