Book contents

- Crafting Poetry Anthologies in Renaissance England

- Crafting Poetry Anthologies in Renaissance England

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Note on the text

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 Books in Process

- Chapter 2 Household Books

- Chapter 3 ‘To the Gentleman Reader’

- Chapter 4 ‘Impos’d designe’

- Chapter 5 A Poetical Rapsody

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Index

- References

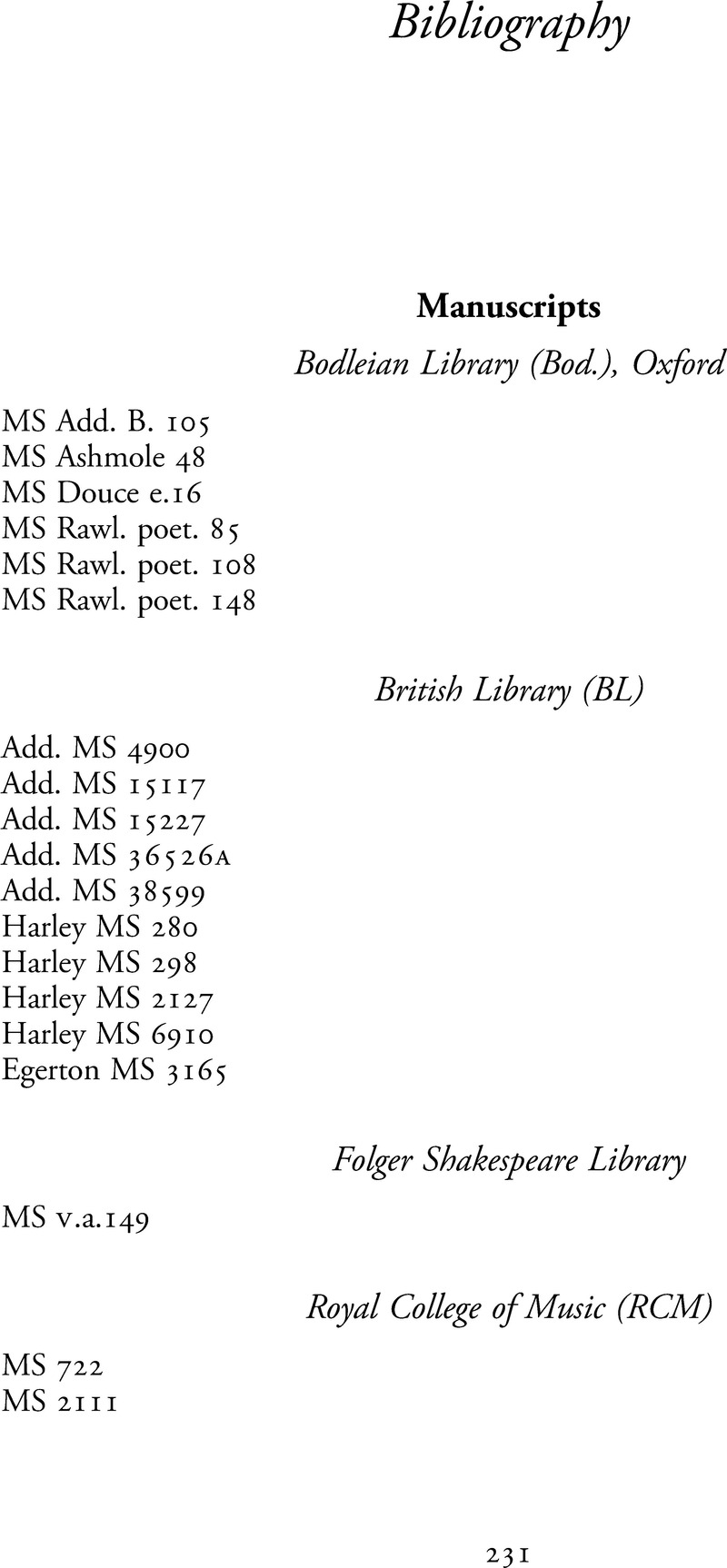

Bibliography

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 23 December 2020

- Crafting Poetry Anthologies in Renaissance England

- Crafting Poetry Anthologies in Renaissance England

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Note on the text

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 Books in Process

- Chapter 2 Household Books

- Chapter 3 ‘To the Gentleman Reader’

- Chapter 4 ‘Impos’d designe’

- Chapter 5 A Poetical Rapsody

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Index

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Crafting Poetry Anthologies in Renaissance EnglandEarly Modern Cultures of Recreation, pp. 231 - 243Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2020