Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of figures

- List of boxes

- List of tables

- Preface

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Distant beginnings: the first 3,000 years

- 3 The Italians invent modern finance

- 4 The rise of international financial capitalism: the seventeenth century

- 5 The “Big Bang” of financial capitalism: financing and re-financing the Mississippi and South Sea Companies, 1688–1720

- 6 The rise and spread of financial capitalism, 1720–1789

- 7 Financial innovations during the “birth of the modern,” 1789–1830: a tale of three revolutions

- 8 British recovery and attempts to imitate in the US, France, and Germany, 1825–1850

- 9 Financial globalization takes off: the spread of sterling and the rise of the gold standard, 1848–1879

- 10 The first global financial market and the classical gold standard, 1880–1914

- 11 The Thirty Years War and the disruption of international finance, 1914–1944

- 12 The Bretton Woods era and the re-emergence of global finance, 1945–1973

- 13 From turmoil to the “Great Moderation,” 1973–2007

- 14 The sub-prime crisis and the aftermath, 2007–2014

- References

- Index

- References

References

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 October 2015

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of figures

- List of boxes

- List of tables

- Preface

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Distant beginnings: the first 3,000 years

- 3 The Italians invent modern finance

- 4 The rise of international financial capitalism: the seventeenth century

- 5 The “Big Bang” of financial capitalism: financing and re-financing the Mississippi and South Sea Companies, 1688–1720

- 6 The rise and spread of financial capitalism, 1720–1789

- 7 Financial innovations during the “birth of the modern,” 1789–1830: a tale of three revolutions

- 8 British recovery and attempts to imitate in the US, France, and Germany, 1825–1850

- 9 Financial globalization takes off: the spread of sterling and the rise of the gold standard, 1848–1879

- 10 The first global financial market and the classical gold standard, 1880–1914

- 11 The Thirty Years War and the disruption of international finance, 1914–1944

- 12 The Bretton Woods era and the re-emergence of global finance, 1945–1973

- 13 From turmoil to the “Great Moderation,” 1973–2007

- 14 The sub-prime crisis and the aftermath, 2007–2014

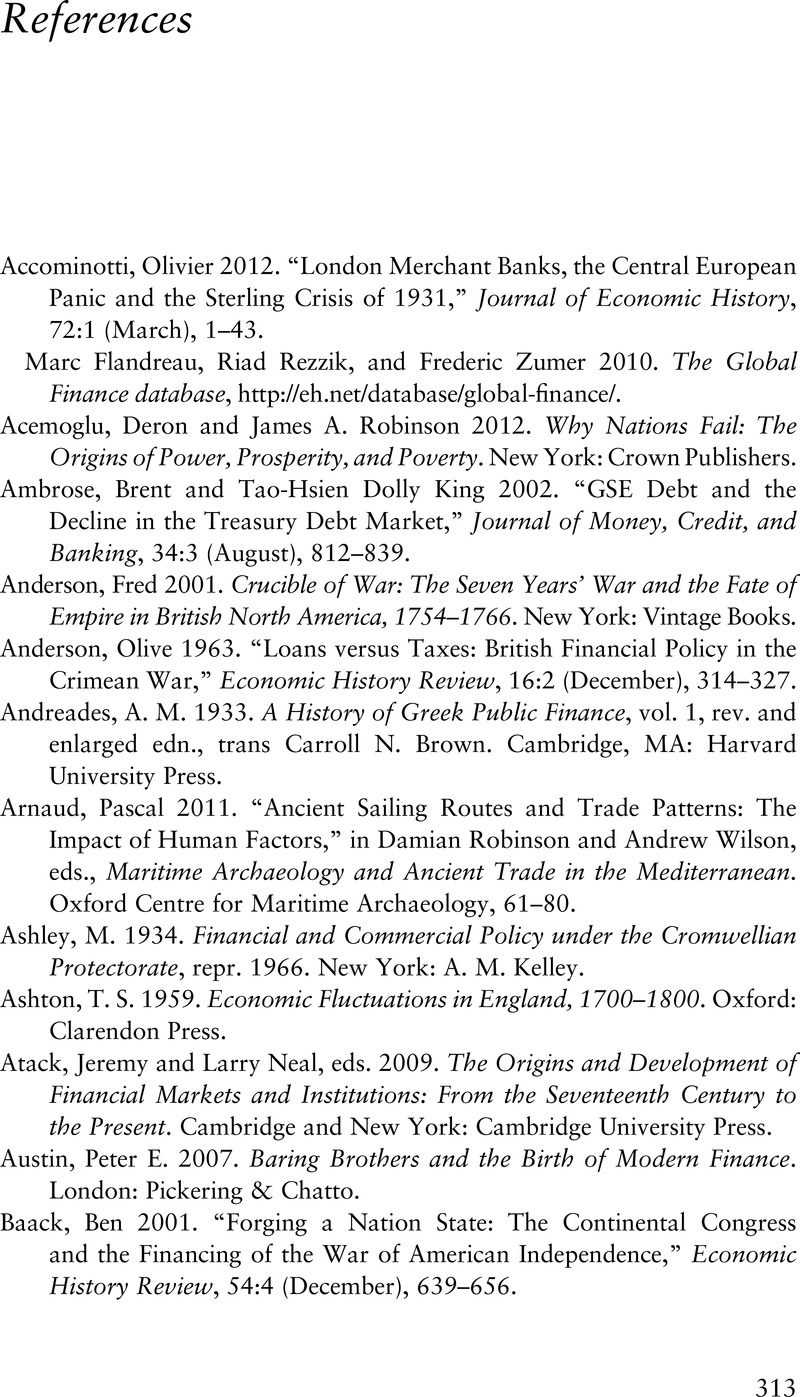

- References

- Index

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- A Concise History of International FinanceFrom Babylon to Bernanke, pp. 313 - 335Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2015