Introduction

In this chapter, we analyze the transnational and domestic conflict configurations on the demand side, that is, among citizens of the European member states. As we argued in the introduction, similar to coming-together federations, the conflict structure in the EU is dominated by the territorial dimension. This dimension produces two lines of conflict: a vertical one, focused on the powers of the polity center vis-à-vis those of the member states, and a horizontal one, revolving around the specific interests of these member states. But the European integration process does not only pit countries against the European center and against each other, it also pits citizens with diverging views of this process against each other within each country. Viewed from the perspective of the general public, we can analyze the extent to which citizens from different countries are divided between themselves and how they are divided among themselves within each country. We shall first analyze the transnational conflicts between citizens from different countries and then focus on the conflicts between citizens within countries.

We expect the transnational conflicts between citizens from different member states to be closely related to the country-specific experiences in the refugee crisis and in the years following the crisis. By contrast, we expect the within-country conflicts among citizens to be rooted in a broader divide between cosmopolitans and communitarians, which is based on structural developments that go beyond the experience of the refugee crisis. In terms of horizontal transnational conflicts, we first resort to our categorization of the variety of EU member states at the onset of the crisis that we introduced in Chapter 2 and have used throughout the book. We expect the perspective of the general public to be shaped by the type of states they are living in: frontline, transit, open destination, closed destination, or bystander states. The criteria underlying this typology such as the countries’ policy heritage, their geographical location on general migration trajectories in Europe, and their immediate crisis experience are expected to have shaped the citizens’ experiences during the crisis and their preferences for policy in the aftermath of the crisis. We do not study how each of these different aspects have affected public opinion but instead assume that they are reflected in the differences observed between country types. Second, beyond the general country types, we especially expect the policy positions adopted by the policymakers during the crisis to have shaped the citizens’ policy preferences, as it is well known that policymakers and their parties are opinion-forming actors of great importance (Zaller Reference Zaun1992; Druckman, Peterson, and Slothuus Reference Druckman, Peterson and Slothuus2013; Slothuus and Bisgaard Reference Statham and Trenz2021). We expect the citizens of frontline states to oppose the citizens of transit, destination, and bystander states because the former countries would benefit most from a reform of asylum policy designed to increase transnational burden sharing. At the same time, we also expect the citizens of the Visegrad 4 (V4) countries – Poland, Hungary, the Czech Republic, and Slovakia – to be the most divergent from those in frontline states, since they have been most mobilized by policymakers against policies designed to increase transnational burden sharing during the refugee crisis. Given the great impact of the mobilization of the V4 on the populations in eastern Europe, it is likely that the citizens of other eastern European bystander states will share the positions of the citizens in the V4 countries.

Turning to the within-country conflicts, we have argued in Chapter 2 that the European integration process can be viewed as part and parcel of a larger process of globalization that restructures national politics in terms of a new structuring conflict (or cleavage) that opposes cosmopolitans-universalists and nationalists-communitarians. The new structuring conflict raises fundamental issues of rule and belonging and taps into various sources of conflicts about national identity, sovereignty, and solidarity. The emerging divide concerns above all conflicts about the influx of migrants, competing supranational sources of authority, and international economic competition. Scholars have used different labels to refer to this new structuring conflict – from GAL-TAN (Hooghe, Marks, and Wilson Reference Hooghe, Marks and Wilson2002), independence-integration (Bartolini Reference Bartolini2005b), integration-demarcation (Kriesi et al. Reference Kriesi2008), universalism-communitarianism (Bornschier Reference Bornschier2010), cosmopolitanism-communitarianism (Zürn and Wilde Reference Zürn and de Wilde2016), and cosmopolitanism-parochialism (De Vries Reference De Vries2017) to the transnational cleavage (Hooghe and Marks Reference Hooghe and Marks2018) and the cleavage between sovereignism and Europeanism (Fabbrini Reference Fabbrini2019: 62f). However, what they all emphasize is that the new divide constitutes a break with the period of “permissive consensus” and that conflicts over Europe have been transferred from the backrooms of political decision-making to the public sphere. At the same time, the new conflict leads to a renaissance of nationalism (and a desolidarization process between nation-states) and a politicization of national political, economic, and cultural boundaries.

These authors agree that the new divide is above all articulated based on two types of issues – immigration and European integration – and that it mainly concerns cultural-political, not economic, aspects of these issues. For multiple reasons – programmatic constraints, internal divisions, incumbency, and so forth – the mobilization potential created by this new conflict has been neglected and avoided (depoliticized) by the mainstream parties (De Vries and van de Wardt Reference De Vries, van de Wardt, Oppermann and Viehrig2011; Green-Pedersen Reference Green-Pedersen and Krogstrup2012; Hooghe and Marks Reference Hooghe, Marks, Jones, Menon and Weatherill2018; Netjes and Binnema Reference Nickell2007; Sitter Reference Skodo2001; Steenbergen and Scott Reference Teigen and Karlsen2004). Consequently, voters turned to new parties with distinctive profiles for their articulation. Over the past decades, it was first the cosmopolitan side that mobilized. In the aftermath of the “cultural revolution” in the 1960s and 1970s, radical left and green parties mobilized the social-cultural segments of the new middle class in the name of cultural liberalism, environmental protection, and multiculturalism. The cultural revolution also transformed the social democratic parties, which, in the process, have become essentially middle-class parties in almost all countries of western Europe (e.g., Gingrich and Häusermann Reference Golby, Feaver and Dropp2015; Kitschelt Reference Klaus, Lévay, Rzeplińska, Scheinost, Kury and Redo1994).

In a second wave of mobilization starting in the 1980s and 1990s, it has been mainly the parties of the radical right that have mobilized the heterogeneous set of the losers of globalization (Kriesi et al. Reference Kriesi2008) and their concerns about immigration and European integration. These parties were mainly newly rising challengers, but in some countries such as Austria and Switzerland, they consisted of transformed established center right parties. These parties all endorse a xenophobic form of nationalism that can be called nativist (Mudde Reference Mudde2007), claiming that states should be inhabited exclusively by members of the native group (the “nation”). Accordingly, the vote for these parties has been shown to be above all an anti-immigration vote (Oesch Reference Ortiz, Myers, Walls and Diaz2008) and, to some extent, a vote against Europe (Schulte-Cloos Reference Schuster2018; Werts, Scheepers, and Lubbers Reference Whitaker and Martin2013) and against the cultural liberalism of the left that has increasingly shaped Western societies (Ignazi Reference Indridason and Kristinsson2003; Inglehart and Norris Reference Jones2016).

The green parties on the one hand and the radical right parties on the other hand mainly rose in northwestern Europe. They have become established forces in the national party systems of their respective countries, even if, for various reasons, the radical right broke through in some of them belatedly. In southern Europe, up to the most recent past, with the exception of the Italian Lega Nord (Betz Reference Betz1993), radical right parties have not been able to gain a foothold. The impact of the new conflict has been more limited in the countries of southern Europe – for reasons that have to do with their political legacy (long-lasting authoritarian regimes and strong communist parties, i.e., a strong “old” left), with their having been emigration countries until more recently, and with the fact that the return to Europe after the authoritarian period was perceived as a return to Western civilization (Diez Medrano Reference Diez Medrano2003). However, under the impact of the combined economic and political crises that shook southern Europe in the more recent past (Hutter and Kriesi Reference Hutter and Kriesi2019a), new parties of the radical left (but hardly any green parties) have surged in Greece, Spain, and (to a more limited extent) Portugal. More recently, parties of the radical right also rose in Italy (Lega) and Spain (Vox). In central–eastern Europe, both types of radical parties have so far been rather weak or transient, due to the communist heritage and the low level of institutionalization of the party system. Instead, in this part of Europe, we have witnessed a radicalization of mainstream parties – of the center right (e.g., in Hungary [Fidesz], Poland [PiS], and the Czech Republic [ODS]) and the center left (e.g., in Romania [PSD]) – which have defended positions previously adopted by the radical right in western Europe.

At the domestic level, we expect that the conflicts are indeed shaped by attitudes about immigration and European integration and that these attitudes are most clearly articulated by the parties taking a nationalist position (the radical right and the conservative-nationalist right in some countries) on the one hand and those taking a cosmopolitan position (the Greens and the radical left) on the other hand. Overall, we shall show that domestic conflicts are more polarizing than transnational conflicts, which is to suggest that the potential for further transnational conflicts is, indeed, quite large. In general, the opponents to immigration are crucial for making asylum policy: If they dominate in some member states, they can induce their governments to legitimately block transnational burden sharing. In line with this argument, we shall see that the more restrictive policies are more likely to be supported than policies that aim at transnational burden sharing.

Measurement

This chapter uses data collected as part of an original cross-national survey fielded in sixteen EU member states in June and July 2021, covering all five types of states we are interested in.Footnote 1 The national samples were obtained using a quota design based on gender, age, area of residence, and education and consist of around 800 respondents per country, amounting to a total of 13,095 respondents. The survey’s larger scope was the study of attitudes related to the multiple crises that have hit the EU since 2008 (such as the financial and sovereign debt crisis, Brexit, and Covid-19) and within this scope, the survey included a section focusing specifically on the refugee crisis. This section consisted of multiple items ranging from attitudes toward migrants and immigration more generally, to performance evaluations of the national governments and the EU in the refugee crisis, to evaluations of specific policies proposed or adopted during the refugee crisis. Additionally, the survey included a host of general political attitudes, enabling our in-depth analysis of the conflict configurations surrounding policies in the refugee crisis. The timing of the survey in the aftermath of the refugee crisis also provides us with two advantages. First, it allows us to compare all the policies that have been proposed or adopted during the different phases of the crisis. Second, rather than measuring agreement with these policies at the peak of the crisis, when respondents might be biased in favor of one policy or another due to contingent considerations, asking them about their evaluations of policies in the aftermath of the crisis allows for a more considered assessment of these policies. In what follows, we describe the items used in detail, as well as the measures employed for systematically comparing conflict configurations between and within countries.

To measure attitudes toward policies, we include a series of six items tapping into agreement with all major types of policies that have been proposed or adopted at the EU level but also policies adopted by member states. The EU policies taken into consideration are (1) the relocation quota, requiring countries to accommodate a share of refugees; (2) relocation compensation, requiring countries to pay compensation to other countries that accommodate refugees; (3) external bordering through EBCG, investing in reinforcing external borders by reinforcing the border and coast guard; (4) Dublin regulation, requiring refugees to be accommodated by the country through which they first entered Europe and in which they were first registered; and (5) externalization, pursuing deals with third countries (such as Turkey and Libya) via financial and other incentives. To this we add as sixth category concerning international policies of member states: (6) internal border control, reinforcing countries’ internal borders by improving border surveillance, building fences, or pushing back migrants by force.

For measuring immigration attitudes, we use a series of eight items tapping into views about the impact of immigrants in several areas (economy, culture, criminality, overall quality of life) and into the degree to which each country should allow various groups of people to come and live there (same race/ethnic group, different race/ethnic group, poorer countries outside Europe, poorer countries inside Europe). This combination of items for measuring immigration attitudes has already been applied in a cross-national setting in the framework of various waves of the European Social Survey (ESS). As the items are all related conceptually and load onto a single factor with Eigenvalue of higher than 1, we combine them into a single index of pro- and anti-immigration attitudes. Beyond immigration attitudes, we also expect party allegiance to be an important driver of within-country conflicts on policy. For measuring party allegiances, we use a standard vote recall question and recode parties in our sixteen countries into eight different party families: radical left, green, social democrats, liberal, conservative-Christian-democratic, radical right, other, and nonvoters. Finally, we also include Euroscepticism, which is measured by a question on whether European integration has gone too far or should be pushed forward.

We examine descriptively the conflict configurations in four different ways. First, we present the kernel-smoothed distributions of the policy-specific attitudes in the different countries and domestic groups. Second, we estimate levels of policy polarization across different groups in terms of country types, pro-/anti-immigration attitudes, party family, and Euroscepticism and focus the bulk of our analysis on summary polarization measures across these groups. The polarization measure we use is based on the Kolmogorov–Smirnov (KS) statistic (see Marsaglia, Tsang, and Wang Reference Martin and Vanberg2003; Siegel Reference Sigelman and Buell1956: 127–136), which quantifies the distance between the empirical distribution functions of two samples. Our choice of the KS statistic is guided by three arguments: First, since we cannot assume a specific shape (e.g., normal) of the distributions of policy agreement across the different groups, this statistic offers a distribution-free alternative to other, parametric measures of distance (e.g., Bhattacharyya distance); second, the KS statistic can be used as a metric, which means it is symmetric (distance between distribution A and B is the same as distance between distribution B and A) and has a finite range from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating larger distances between the compared distributions; and third, the statistic detects a wider range of differences between two distributions than simply comparing summary statistics such as the mean or the median.

Finally, we attempt to reduce the complex conflict configurations by relying on multidimensional scaling (MDS) procedures. These procedures are designed to place the different entities (in our case, member states, as well as social groups defined by their immigration attitudes and partisanship) in a low-dimensional (typically two-dimensional) space. The distances between the entities in the resulting space reproduce their policy distances as closely as possible. The substantive meaning of the spatial dimensions lies in the eyes of the beholder; one relies on the raw data to come up with an interpretation of the dimensions, but of course this is more art than statistics. Finally, we also use ordinary regression analysis to show how the two types of conflicts relate to each other.

Transnational Conflict Configurations

Transnational Polarization

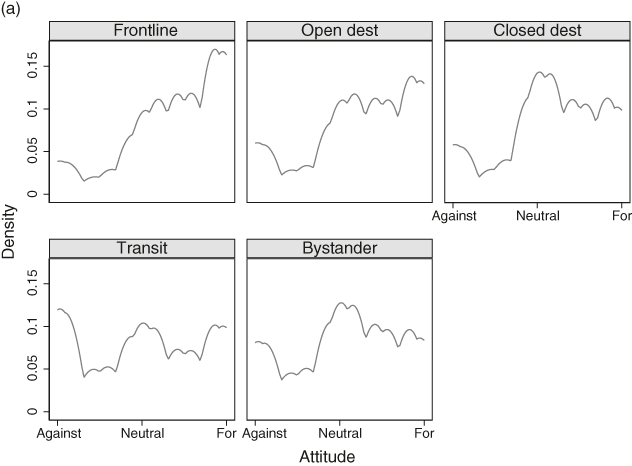

To explore the horizontal line of conflict between member states among the citizens, we start by looking at the distribution of support in our main country types in order to examine the direction of the attitudes toward selected policies (Figure 13.1). Generally, regardless of policy type, we notice that the public in frontline and transit states differs the most from the public in other states in terms of policy support. With respect to relocation (Figure 13.1a), in frontline states, the attitude distribution is heavily skewed in favor of the relocation quota, which is unsurprising because relocation policies would alleviate their immediate burden. By contrast, in transit states, the public is most opposed to the relocation quota, as these states are neither immediately affected by the problem pressure nor ultimate destinations of the migrant flows. The distribution of support is very similar in destination states, of both the closed and open kind, and in bystander states, with respondents being somewhat more positive toward the policy but with a large neutral share of respondents. With regard to the Dublin regulation (Figure 13.1b), again unsurprisingly, respondents in frontline states are the ones most opposed to it, followed by those in the transit states. By contrast, those in the bystander and destination states are rather neutral. Finally, Figures 13.1c and 13.1d indicate that external bordering via the reinforcement of the EBCG and externalization via deals with third countries are the least polarizing policies on the demand side, with similar distributions across all country types that are all heavily skewed toward neutral-positive attitudes. Transit states are the only ones that slightly diverge in the sense that they have an even higher share of positive attitudes toward these policies than other country types do.

(a) Relocation quota;

(b) Dublin regulation;

(c) EBCG;

(d) externalization

Figure 13.1 Policy-specific distribution of support, by country type.

To further explore the transnational line of conflict between member states on the demand side, we construct measures of polarization between countries by policy type for each country in our dataset. This allows us to analyze the contentiousness of policies more systematically but also to observe patterns that might go beyond our general five country types by looking at each country individually and identifying potential coalitions. Table 13.1 presents the average KS distance between the distribution of policy support of each country versus the other fifteen countries in the dataset. Higher values indicate countries that are most dissimilar to the other countries when it comes to a particular policy.

Table 13.1 Transnational polarization by policy and country, Kolmogorov–Smirnov statisticFootnote a

| Type | Country | Quota | Compensation | Dublin | EBCG | Internal border | Externalize |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frontline | Spain | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.09 |

| Italy | 0.26 | 0.23 | 0.15 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.11 | |

| Greece | 0.21 | 0.18 | 0.21 | 0.13 | 0.08 | 0.08 | |

| Open destination | Sweden | 0.14 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.08 |

| Germany | 0.19 | 0.18 | 0.12 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.08 | |

| Netherlands | 0.15 | 0.17 | 0.14 | 0.12 | 0.09 | 0.11 | |

| Closed destination | UK | 0.17 | 0.16 | 0.21 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.08 |

| France | 0.15 | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.08 | 0.10 | 0.12 | |

| Transit | Hungary | 0.23 | 0.28 | 0.17 | 0.10 | 0.09 | 0.11 |

| Austria | 0.16 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.07 | |

| Bystander | Ireland | 0.16 | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.16 | 0.12 | 0.08 |

| Finland | 0.15 | 0.14 | 0.18 | 0.12 | 0.09 | 0.10 | |

| Romania | 0.13 | 0.17 | 0.12 | 0.09 | 0.12 | 0.08 | |

| Latvia | 0.31 | 0.25 | 0.11 | 0.18 | 0.10 | 0.12 | |

| Poland | 0.21 | 0.23 | 0.13 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.09 | |

| Portugal | 0.15 | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.19 | 0.21 | 0.08 | |

| Average | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.15 | 0.12 | 0.10 | 0.09 |

a The KS distances in the dataset represent averages over the fifteen distances between each selected country and the other fifteen countries. Values in bold represent county average KS distances higher than the overall average KS distance for a particular policy.

Indeed, in line with the visual insights from Figure 13.1, the relocation policies (quota and compensation) have been the most contested between member states, followed closely by the Dublin regulation. By contrast, internal bordering and externalization appear to be the least divisive issues between member states at the demand level. This difference in the divisiveness of policies on the demand side closely follows the patterns on the supply side and the actual policy outcomes of these proposals. While internal burden sharing based on quota and compensation proposals had failed, with countries being highly divided on the issue, externalization based on deals with third countries (such as the EU–Turkey agreement was eventually (one of) the arguably successful policies. Therefore, the EU-Turkey episode, which dominated most of the peak phase of the crisis and was the single most politicized policy decision taken during this crisis (see Chapter 4), left a positive legacy among the public – most likely due to its successful implementation: In the aftermath of the crisis, externalization to third countries appears as the least polarizing option on the demand side.

Beyond these general patterns, countries also diverge according to their type and centrality in the crisis. While the distance measure used here does not tell us the direction of the country-specific deviations (for or against the policy) from the mean, we can interpret these deviations based on the insights from Figure 13.1. With regard to relocation, we see that several frontline states (Italy and Greece), bystander states (Latvia and Poland), and transit states (Hungary) appear to be most polarized. As is already apparent from Figure 13.1, it is above all citizens in Italy and Greece, as the most affected frontline states, who favor these policies because they would reduce their immediate burden, whereas bystander and transit countries are the most opposed to these policies. Going beyond our country types, we see more specifically that not all transit and bystander states are polarized to the same degree. Together with Latvia, Hungary and Poland stand out the most. This indicates that the pattern observed at the level of decision-makers during the crisis, when the resistance of the Visegrad group (V4) was formed against relocation, persists among the citizen public in the aftermath of the crisis.

Among the destination states, public opinion in Germany is the most transnationally polarized with respect to relocation, even if to a lesser extent than public opinion in Latvia, Poland, and Hungary. This is unsurprising, given the centrality of Germany in the relocation debate. With regard to the Dublin regulation, the countries whose positions stand out the most are Greece and the UK, the former suffering directly from its dysfunctionality, whereas the latter, a geographically insulated, closed destination state, benefited most from shifting the burden to any other state along the migration routes. Finally, with regard to internal and external bordering (EBCG) and externalization, we see smaller deviations, with most countries having similar distributions in terms of agreement with these policies, with the exception of some bystander states (in particular Portugal), which seem to deviate the most when it comes to agreement with these issues.

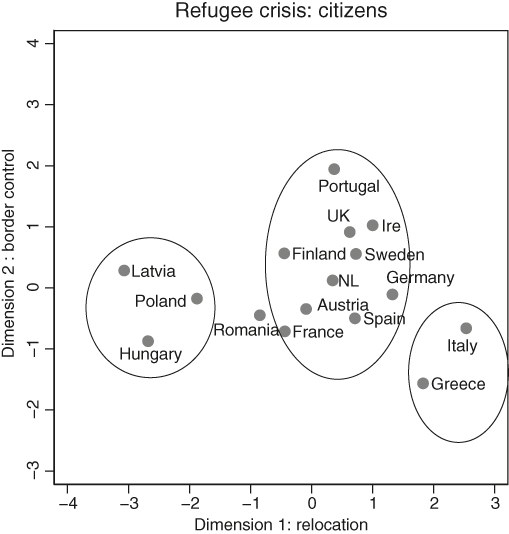

In Figure 13.2, we examine the transnational conflict configuration via multidimensional scaling in a bidimensional space determined by attitudes toward relocation (x-axis) and attitudes toward border control (y-axis). This representation of the transnational conflict configurations confirms that the relocation policy is structuring the space the most. We have less variation among the member states on the border control dimension and hardly any with regard to externalization. The horizontal alignment of member states in terms of relocation shows three clusters of countries. On the left-hand side, opposed to relocation, we have members of the Visegrad group – Hungary and Poland (joined by Latvia) – as the most vocal opponents of relocation, whereas on the right-hand pro-relocation side, we have the two frontline states most heavily hit by the crisis – Italy and Greece.

Figure 13.2 Transnational conflict configuration according to citizens’ policy positions in the refugee crisis: MDS solution

All in all, our analysis of transnational conflict reveals that most of these conflicts on the demand side are being structured around the relocation debate (involving either quotas or compensation), while other policies involving external or internal bordering or externalization are comparatively less polarizing at the transnational level. Patterns on the supply-side level are mirrored by the perspective of the general public even in the aftermath of the crisis, being clearly structured around country types and coalitions with frontline states and the Visegrad group at opposing poles of the debate.

Domestic Conflict Configurations: Immigration Attitudes and Partisan Support

We study the domestic conflict configurations from two perspectives. On the one hand, we focus on the configurations defined by immigration-related attitudes, and on the other hand, we analyze the conflicts between party families. The configurations between groups with pro- and anti-immigration attitudes define the political potentials for mobilization by the political parties. These conflicts between attitudinal groups remain latent as long as they are not mobilized by political actors. Among possible political actors, we study only parties. However, parties are among the key actors when it comes to the mobilization of immigration-related attitudes. The divisions between attitudinal groups is expected to be larger than the corresponding polarization between parties, as parties offer bundles of issue positions, and immigration is only one of many relevant issues.

Distribution of Immigration Attitudes

For our study of the refugee crisis, it is above all immigration-related attitudes that can be expected to determine the policy-specific substantive demands. Consistent with earlier work, these attitudes vary considerably across countries as well as across time, which allows for context-specific politicization of the underlying structural conflict between cosmopolitans and communitarians in each of the different member states. We shall first consider the policy-specific conflict configurations in the sixteen countries based on the immigration attitudes, before presenting the respective conflict configurations based on the partisan preferences of the voters in the different member states.

Based on our factor for immigration-related attitudes, we have created three categories of citizens: those opposing immigration, those having a rather neutral attitude with respect to immigration, and those favoring immigration.Footnote 2 Table 13.2 presents the immigration attitudes by member states, which are ordered from the country most opposed to immigration to the country most favorable to immigration. These distributions reflect the situation in summer 2021. Overall, there is a slight plurality of 42.8 percent of citizens favoring immigration, compared to 36.5 percent opposing it. However, the countries differ considerably in this respect. There are a number of countries where pro-immigration groups constitute a minority, while a plurality of the citizens oppose immigration. Importantly, the rank order of the countries in Table 13.2 does not align well with the different types of states we have distinguished throughout this study based on their experience during the refugee crisis. Thus, among the member states most opposed to immigration we find an eastern European bystander state (Latvia), a frontline state (Greece), a transit state (Hungary), and a destination state (France). Among the countries most favorable to immigration are four bystander states from different geographical regions of Europe (Ireland, Portugal, Romania, and Poland) as well as the UK, a restrictive destination state.

Table 13.2 Immigration attitudes by country (ordered by share against)

| Country | Against | Neutral | Pro |

|---|---|---|---|

| Greece | 54.2 | 18.8 | 27.1 |

| Hungary | 50.6 | 19.8 | 29.7 |

| Latvia | 48.0 | 26.9 | 25.1 |

| France | 48.0 | 21.6 | 30.4 |

| Austria | 43.7 | 18.7 | 37.6 |

| Sweden | 40.2 | 19.8 | 40.1 |

| Netherlands | 39.7 | 23.2 | 37.0 |

| Finland | 38.9 | 18.5 | 42.6 |

| Germany | 35.1 | 19.9 | 45.0 |

| Italy | 32.3 | 20.1 | 47.6 |

| Spain | 30.5 | 22.0 | 47.5 |

| Poland | 29.7 | 21.1 | 49.2 |

| Romania | 27.7 | 23.4 | 48.9 |

| UK | 27.4 | 22.1 | 50.5 |

| Ireland | 19.6 | 16.2 | 64.3 |

| Portugal | 16.9 | 19.6 | 63.5 |

| Total | 36.5 | 20.7 | 42.8 |

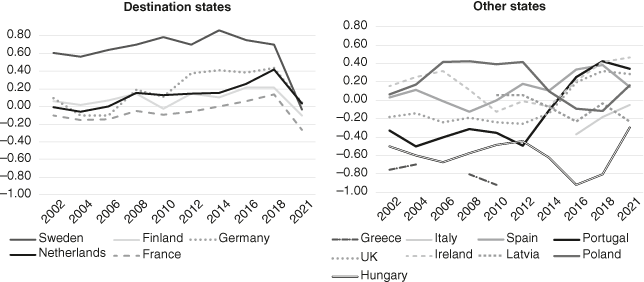

We have also created a factor for immigration attitudes that is directly comparable to the factor that we obtain based on ESS data. The ESS data cover the period 2002–2018 for most of our sixteen countries, allowing us to compare the current immigration attitudes to attitudes reaching back to 2002. Figure 13.3 presents the development of immigration attitudes over time. In this figure, the countries have been grouped according to their over-time patterns. The first graph includes three open destination states (Germany, the Netherlands, and Sweden), a closed destination state (France), and a bystander state (Finland). The support for immigration has varied across these five countries in the past, but in all these countries, it has collapsed in the past few years. The collapse occurred after 2018, that is, at a moment when the refugee crisis was already a past memory. The collapse was most striking in Sweden, which used to be by far the country most favorable to immigration. By summer 2021, the support for immigration in Sweden had converged with the support in Germany, Finland, and the Netherlands below the mid-point of the scale. Table 13.3 shows that the collapse in Sweden occurred across the political spectrum, even if the radical left proved to be somewhat more resistant to the general movement against immigration than the rest of the parties. At the same time, the share of the radical right, the party most opposed to immigration, has more than doubled in Sweden.

Figure 13.3 Development of immigration attitudes over time, mean factor scores by country

Table 13.3 The case of Sweden

| Family_vote | 2018 | 2021 | Mean | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Share | Mean | Share | 2021–2018 | |

| Radical left | 1.09 | 0.21 | 0.79 | 0.11 | –0.30 |

| Green | 1.33 | 0.06 | 0.39 | 0.04 | –0.94 |

| Social Democrats | 0.82 | 0.30 | 0.17 | 0.34 | –0.65 |

| Liberal | 0.83 | 0.07 | –0.02 | 0.03 | –0.81 |

| Conservative-Christian-Democrats | 0.52 | 0.24 | –0.21 | 0.22 | –0.71 |

| Radical right | –0.31 | 0.11 | –0.99 | 0.26 | –0.68 |

| Total | 0.71 | 1 | –0.11 | 1 | –0.82 |

| n | 1,287 | 526 | |||

The second graph in Figure 13.3 shows the countries where the support for immigration has been rather stable or has improved more recently, albeit from very different levels. This is a mixed group of countries that includes bystander states (Ireland, Poland, and Portugal), frontline states (Greece and Italy), a transit state (Hungary), and a closed destination state (the UK) but not a single open destination state. In two of these countries (Hungary and Italy), support for immigration reached a low point in 2016, at the height of the refugee crisis, from which it recovered in the more recent past. The contrasting developments in the two sets of countries led to a convergence of immigration attitudes in the countries under study: The standard deviation of the country means fell from 0.37 in 2018 to 0.30 in 2021.Footnote 3

To account for these contrasting developments, we have calculated the correlation between the share of the citizens in a given country that considers immigration one of the most important problems facing their country and/or the EU and the level of immigration attitudes in 2021: This correlation is negative and substantial (–0.71), which means that the greater the salience of immigration in a given country in 2021, the lower the support for immigration. The refugee crisis has been most salient in open destination and transit states.

Asked which crisis before the Covid-19 pandemic had been the greatest threat for the survival of the European Union – the refugee, financial, poverty/unemployment, or Brexit crisis – 41 percent of the citizens in open destination and 43 percent of those in transit states mentioned the refugee crisis, compared to only 21 percent in frontline states, 28 percent in restrictive destination states, and 30 percent in bystander states. Since the refugee crisis, the salience of immigration issues has, if anything, increased once again. Not only roughly one third (32 percent) considered the refugee crisis as the most threatening crisis retrospectively, but by summer 2021, almost half (47 percent) of the citizens in our sixteen countries considered immigration as one of the most important problems facing their country and/or the EU. The salience of immigration had increased in all countries except Sweden and Germany (the two most important destination countries in the crisis); Austria and Hungary (the transit states); and Poland (a member of the V4), where it had already been very high previously.

Policy Support by Immigration Attitude

Table 13.4 presents the domestic policy–specific polarization between pro- and anti-immigration groups. The policies are arranged from left to right as in the previous table. As can be seen, similar to the transnational level, the relocation quota (and the related compensatory measures) are the most polarized policies. External and internal border control measures are also highly polarized, while the Dublin regulation and even more so externalization are less polarized among attitudinal groups. Compared to the conflict configurations between countries, the level of polarization is, however, generally considerably higher between the attitudinal potentials within the member states. This means that the latent conflict potential has not been fully mobilized in transnational conflicts. As we shall see, even at the domestic level, this potential has not been fully mobilized.

Table 13.4 Domestic polarization between pro- and anti-immigration groups, by policy and country, Kolmogorov–Smirnov statisticFootnote a

| Type | Country | Quota | Compensation | Dublin | EBCG | Internal border | Externalize |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frontline | Spain | 0.37 | 0.30 | 0.33 | 0.30 | 0.35 | 0.19 |

| Italy | 0.20 | 0.21 | 0.33 | 0.42 | 0.31 | 0.18 | |

| Greece | 0.22 | 0.23 | 0.20 | 0.39 | 0.39 | 0.13 | |

| Open destination | Sweden | 0.40 | 0.32 | 0.22 | 0.52 | 0.35 | 0.21 |

| Germany | 0.40 | 0.32 | 0.19 | 0.40 | 0.43 | 0.12 | |

| Netherlands | 0.45 | 0.37 | 0.11 | 0.30 | 0.23 | 0.13 | |

| Closed destination | UK | 0.33 | 0.30 | 0.28 | 0.43 | 0.40 | 0.20 |

| France | 0.59 | 0.48 | 0.29 | 0.45 | 0.37 | 0.18 | |

| Transit | Hungary | 0.52 | 0.43 | 0.13 | 0.31 | 0.42 | 0.07 |

| Austria | 0.58 | 0.42 | 0.23 | 0.44 | 0.43 | 0.08 | |

| Bystanders | Ireland | 0.50 | 0.43 | 0.16 | 0.30 | 0.32 | 0.15 |

| Finland | 0.52 | 0.45 | 0.15 | 0.43 | 0.39 | 0.18 | |

| Romania | 0.41 | 0.40 | 0.18 | 0.16 | 0.18 | 0.13 | |

| Latvia | 0.47 | 0.43 | 0.22 | 0.26 | 0.32 | 0.08 | |

| Poland | 0.42 | 0.38 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.22 | 0.18 | |

| Portugal | 0.45 | 0.42 | 0.10 | 0.28 | 0.27 | 0.12 | |

| Average | 0.43 | 0.37 | 0.20 | 0.35 | 0.34 | 0.15 |

a The KS distances in the dataset represent distances between the pro-immigration and the anti-immigration group within each selected country. Values in bold represent county KS distances higher than the overall average KS distance for a particular policy.

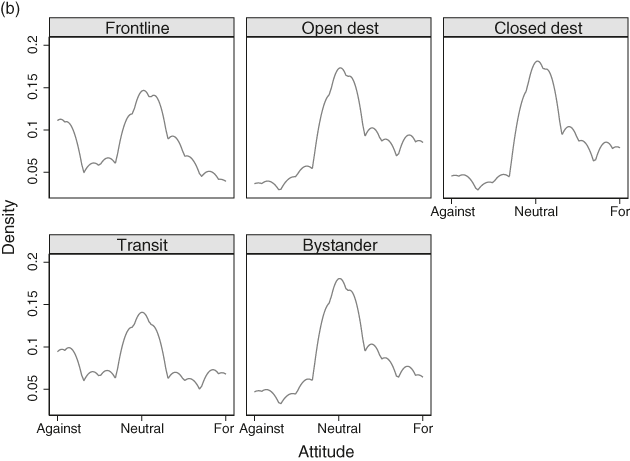

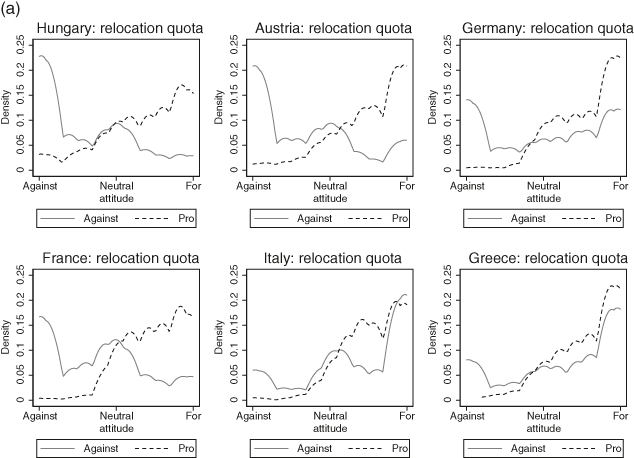

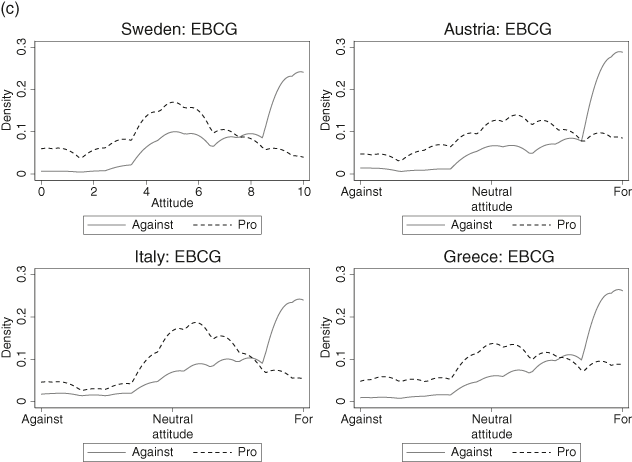

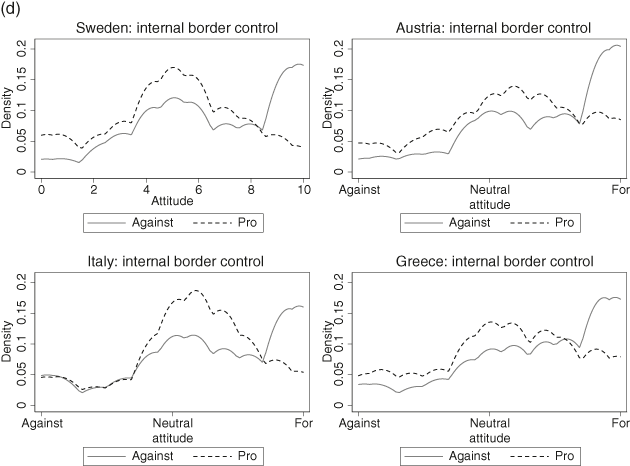

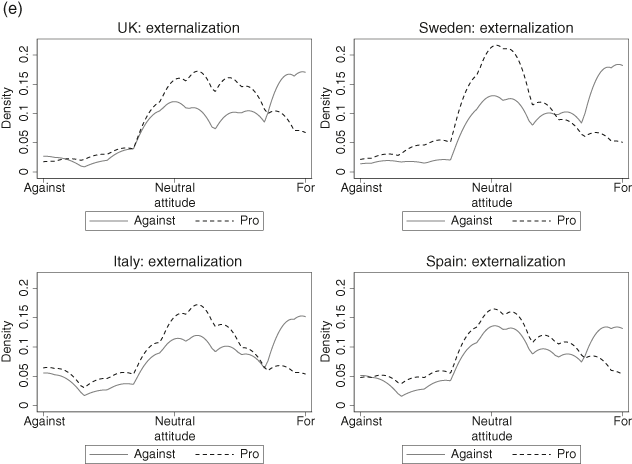

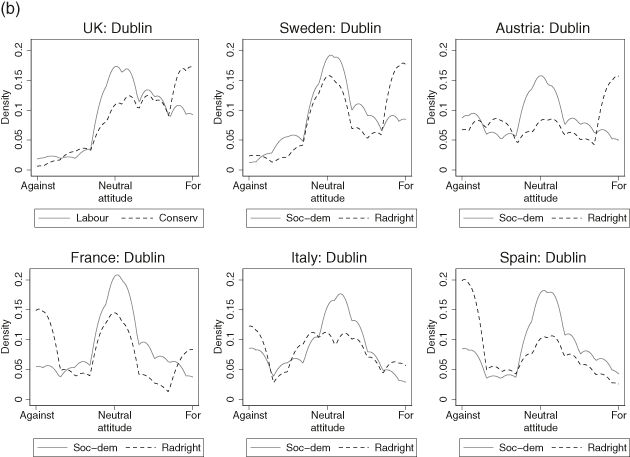

Looking at country differences, there is a strong possibility of conflict between pro- and anti-immigration groups with respect to relocation quotas in some countries. Thus, polarization between attitudinal groups is highest in France, a restrictive destination state, and in the transit and bystander states. It is somewhat lower in the open destination states and much lower in the frontline states of Greece and Italy. As is illustrated by Figure 13.4a for some selected countries, pro-immigration groups are generally in favor of relocation quotas, which means that domestic polarization is high where anti-immigration groups oppose such quotas. With the exception of frontline states like Greece and Italy, this is the case in all types of countries. Citizens who are in favor of immigration see quotas as a possible measure to accommodate refugees in an equitable way. Citizens who are opposed to immigration do not wish to adopt policies, such as relocation quotas, that allow refugees to stay in Europe. The anti-immigration citizens in frontline states are an exception, most likely because their countries would benefit from relocation schemes.

(a) Relocation quota: support;

(b) Dublin regulation;

(c) external border control;

(d) internal border control;

(e) externalization

Figure 13.4 Policy support by immigration attitudes.

With regard to the Dublin regulation (Figure 13.4b), the positions of the pro-immigration groups are not quite clear: Large parts of these groups take a neutral position in all types of countries. Even the opponents of immigration are somewhat uncertain about this regulation, but clear-cut minorities among them support it in destination and transit states (the UK, Sweden, and Austria are examples) where the regulation is intended to keep refugees out, and oppose it in frontline states (Spain and Italy) where the regulation is intended to keep refugees in the country, and in France (whose opponents to immigration behave in this case like opponents in frontline states). By contrast, with regard to border control measures, the position of pro-immigration groups is not so clear, while they are generally supported by opponents of immigration, as is illustrated by Figures 13.4c and 13.4d. Externalization (Figure 13.4e), finally, is generally supported by both groups, but to a somewhat greater extent by the opponents to immigration, especially in destination states like the UK and Sweden.

Overall, this analysis clarifies that it is the opponents to immigration who could be decisive for the policy options in the EU member states. They oppose relocation quotas and, in frontline states, the Dublin regulation, which creates potential obstacles for these solutions. Given that they constitute large minorities or even a plurality in many countries – above all in transit states; in Latvia, Greece, and France; but also in open destination states like Sweden and the Netherlands – the governments of the respective member states are legitimately opposing these policy proposals. By contrast, the opponents to immigration are much more favorably disposed to externalization and internal and external border controls. While the pro-immigration groups are not as supportive of the latter policies, they are not clearly opposed to them, which makes this type of solution potentially more consensual.

In addition to immigration attitudes, we have also analyzed the political potential of Euroscepticism (not shown here due to space considerations). The twin issues – immigration and European integration – solicit similar conflict configurations in the member states, which is why we do not pursue the European integration attitudes any further here.

Policy Support by Party Family

Chapter 6 has shown that partisan conflicts are the most likely venue for the articulation of conflicts about refugee-related policy episodes in member states. Table 13.5 presents the overall polarization between voters from different party families with respect to the six policies in comparison to transnational polarization and domestic polarization by attitudes. As expected, attitudinal groups are more polarized than are political parties. In particular, the partisan conflicts are more attenuated with regard to relocation, but also with regard to border control. In contrast, there are few differences between attitudinal and partisan polarization concerning the Dublin regulation and externalization. However, even if they are less polarized than the attitudinal groups, note that policy-specific partisan conflicts are still a lot more polarized than the corresponding transnational conflicts, which confirms the critical role of domestic opposition to EU policy proposals.

Table 13.5 Comparison of overall polarization, transnationally and domestically by attitudes and party family, across policies: Kolmogorov–Smirnov statistic

| Level | Quota | Compen-sation | Dublin | EBCG | Internal border | Externalize |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transnational | 0.18 | 0.17 | 0.15 | 0.12 | 0.10 | 0.09 |

| Domestic: attitudes | 0.43 | 0.37 | 0.20 | 0.35 | 0.34 | 0.15 |

| Domestic: partisan | 0.24 | 0.22 | 0.18 | 0.22 | 0.24 | 0.18 |

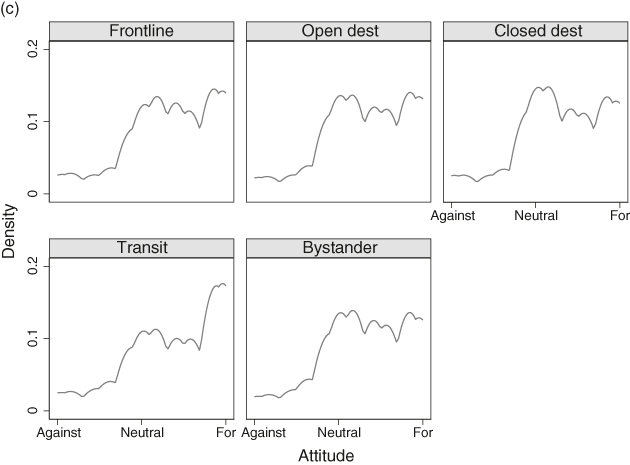

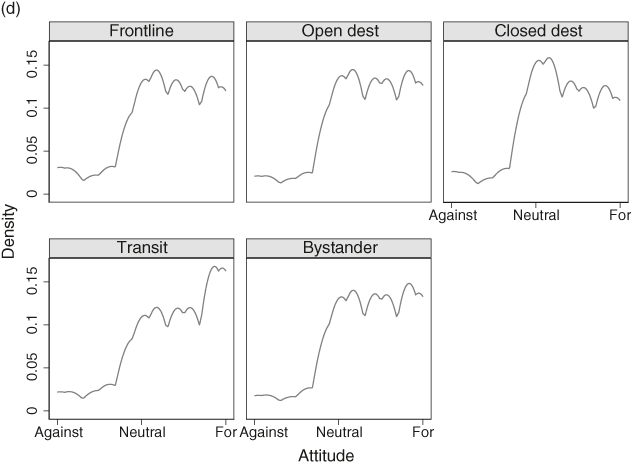

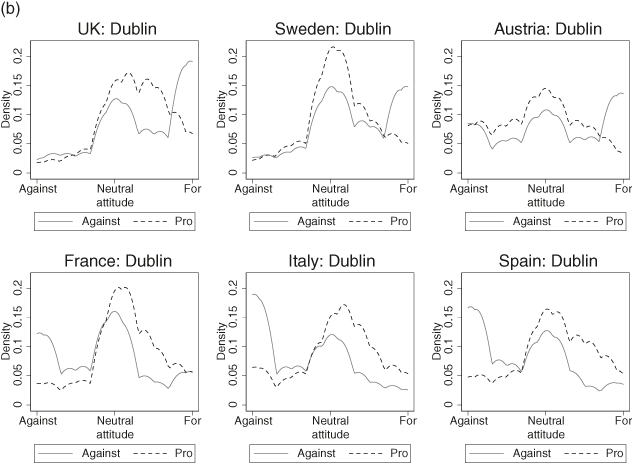

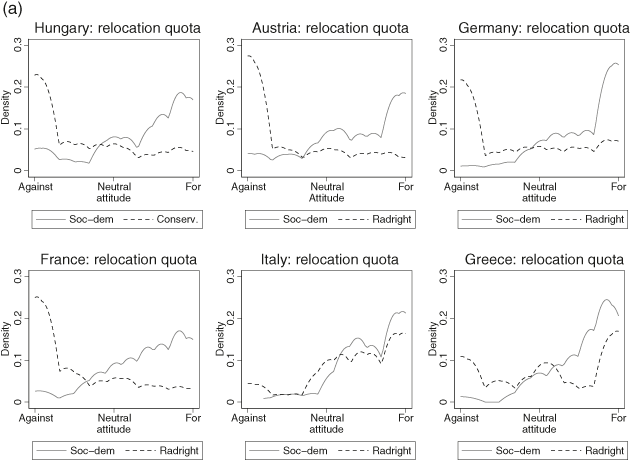

Considering the country differences in detail, with respect to relocation quotas, the partisan conflict remains intense between the left and the right in all countries except frontline states. This is shown in Figure 13.5a, where we present the distribution of policy-specific attitudes for the center left (social democrats) and the radical right (or the national-conservative right in countries without a significant radical right) for some selected countries. There is also a reduced but still important conflict with respect to border control (not shown). The radical right is embracing border control internally and externally, while the center left is not adopting clear-cut positions in this regard. Greece is exceptional to the extent that, in this country, not only the radical right but also the center left is in favor of the reinforcement of the external borders, while it is the radical left (Syriza) that opposes this measure to some extent. By contrast, with respect to the Dublin regulation and externalization, we do not find any attenuation of partisan conflicts compared to attitudinal polarization. In line with the previous results, the left is uncertain about this regulation, while the radical right tends to embrace it in destination and transit states but oppose it in frontline states (Figure 13.5b). Externalization, which was the least contested between attitudinal groups, turns out to be more contested between parties than between attitudinal groups in closed destination states, transit states, and Poland (not shown). In destination states, the right is somewhat more in favor of externalization than the left is. By contrast, in frontline states, there is hardly any difference between the two opposing sides, as they both tend to support externalization to the same extent.

(a) Relocation quota;

(b) Dublin regulation

Figure 13.5 Policy support by party family.

Overall, we can conclude that domestic partisan polarization between the left and right, while less pronounced than attitudinal polarization, is still very intense. Moreover, there are fewer differences between the policy domains in terms of partisan polarization than in terms of attitudinal polarization. Finally, partisan polarization is particularly pronounced in the closed destination states.

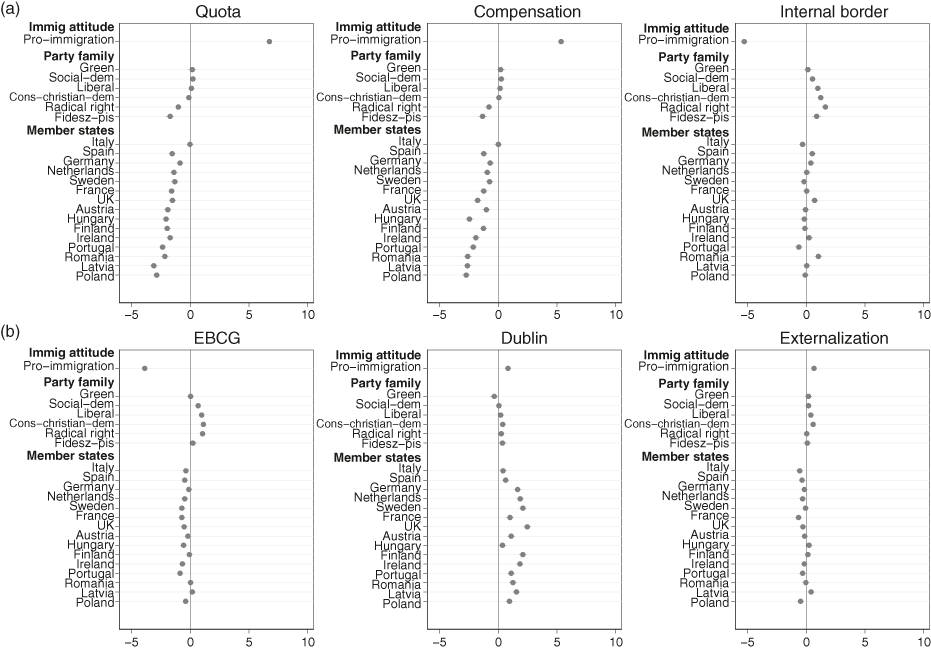

Transnational and Domestic Policy-Specific Conflict Configurations Combined

In this section, we analyze the joint configuration of the transnational and domestic conflicts by way of regression. Figure 13.6 presents the corresponding results in graphical form. For each policy, there are three types of effects – attitudinal effects, party family effects (with a specific effect for Fidesz and PiS), and country effects. The bigger an effect parameter in this graph, the more closely the corresponding aspect is associated with the conflict about a given policy. All effects are the net effects, controlling for the effects of the other aspects. Thus, the attitudinal effects represent the remaining effects of the immigration attitudes that have not been mobilized by the domestic parties. The country effects represent the levels of policy support in the different countries that are not attributable to immigration attitudes and to partisan conflicts in the respective countries but correspond to the aggregate policy position of the country’s citizens irrespective of these aspects. Greece, a key frontline state, is the reference category for the country effects, which means that the country effects indicate to what extent the population in a given country differs from the Greeks. Except for the immigration attitude, all variables are dummies, which means that the effects correspond to the impact on the 0 to 10 scale of the policy assessment. The immigration attitude has also been rescaled to the 0 to 1 range, which means that the effects shown correspond to the maximum effect of these attitudes.

Figure 13.6 Transnational and domestic conflict configurations according to citizens’ policy positions in the refugee crisis: OLS regression coefficients

Let us first consider the relocation quotas and the corresponding compensation proposals: Here, all three factors strongly contribute to the conflict. The pattern of results is very similar for the two types of proposals. First, the attitudinal conflict is the main driver of these attitudes, even if we control for partisan and country effects. People who support immigration are in favor of quotas, and people who oppose immigration are against them. The very strong effect of immigration attitudes implies that the partisan mobilization here has been weak, and this issue could become much more politicized in the future. This is to suggest that, given the widespread opposition to immigration across Europe, further pursuing policies involving quotas and related proposals is likely to be met with widespread contestation. In partisan terms, with the exception of the radical right, there are few differences between party families with respect to quotas. It is the radical right that gives political voice to the opposition to quotas. The only exceptions to this pattern occur in Hungary and Poland, where Fidesz and PiS, officially two conservative parties, are even more opposed to quotas than is the radical right. In terms of between-country differences, Italy and Greece are the two nations that really stand out. Italy and Greece have – by far – the highest support for quotas. This is not simply a frontline country effect, as support for quotas is significantly lower in Spain.

Internal border controls and the reinforcement of external borders (EBCG) are also strongly associated with immigration attitudes, but these policies are preferred by immigration opponents. Accordingly, parties on the right are more supportive of such policies than are parties on the left. For these policies, however, Fidesz and PiS do not stick out as much as they did for quotas and compensations. There are hardly any country differences with regard to internal border controls, except that the British and the Romanians perceive them in a somewhat more positive light than the other Europeans do, and the Portuguese are somewhat more critical in this respect. Country differences are also more contained in terms of reinforcing external borders, but populations of destination and bystander states tend to be slightly more critical of such policies than Greeks, Italians, and Germans are.

In contrast to the four previous policies, assessments of the Dublin regulation are hardly associated with immigration attitudes in general. Partisan differences are also generally rather small. With regard to this policy, country differences dominate. All countries, even Spain, are more in favor of this regulation than are the Hungarians and the citizens of the two frontline states most hit by the crisis. Finally, as we have already seen, externalization is least structured by the three effects we are considering here. It is slightly more favored by people holding pro-immigration attitudes. Liberal and conservative parties are somewhat more supportive of such policies, and there are no systematic country patterns.

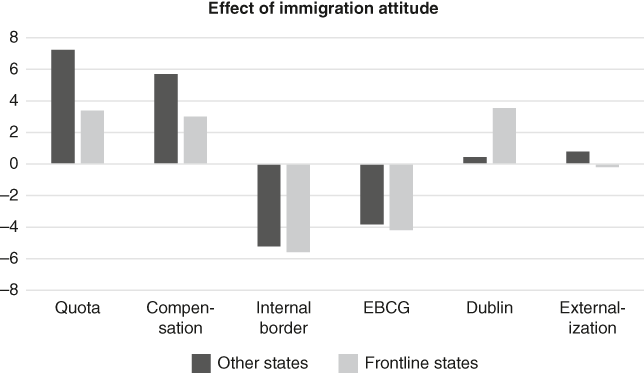

We have run separate regressions with an interaction term to account for possible different effects of immigration attitudes in frontline states. Figure 13.7 presents these differences for the six policy proposals. Two results stand out. On the one hand, the effect of immigration attitudes on the policy assessment is clearly reduced in the frontline states for quotas and compensatory measures because, as we have seen, even those who oppose immigration are also rather in favor of quotas. On the other hand, while immigration attitudes have no effect on the assessment of the Dublin regulation in most countries, this regulation is clearly more accepted by people holding pro-immigration attitudes in frontline states.

Figure 13.7 The effect of immigration attitudes on the six policy positions in frontline states and other states

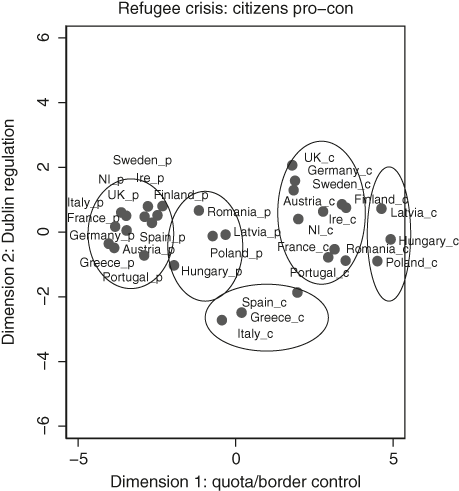

Next, we present the joint distribution of conflict configurations based on multidimensional scaling (MDS). While the regression approach analyzes the configurations policy by policy, MDS techniques allow for a configurational analysis that takes into account all the policies at the same time. We first present the combination based on immigration attitudes (Figure 13.8) before turning to the combination based on partisan conflicts (Figure 13.9). The configuration based on attitudes has a dominant horizontal dimension representing the major policies that have been adopted during the crisis – relocation quota and internal and external border control measures, and a secondary vertical dimension representing above all the failed Dublin regulation. The most consensual policy – externalization – hardly contributes to the structuring of the joint space, nor does the Dublin regulation contribute to the structuring of the joint space with party families.

Figure 13.8 Transnational and domestic conflict configurations according to citizens’ policy positions (p = pro/c = contra immigration) in the refugee crisis and immigration attitudes: MDS solution

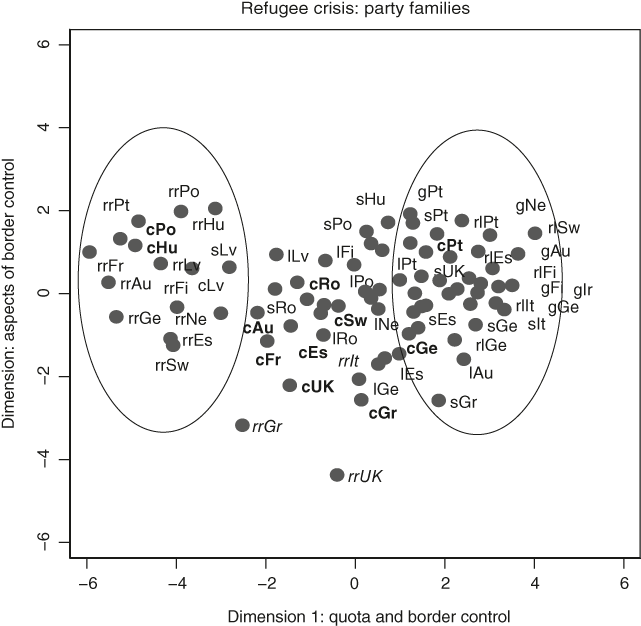

Figure 13.9 Transnational and domestic conflict configurations according to citizens’ policy positions in the refugee crisis and party families: MDS solutiona

aNot all parties are labeled so as to avoid cluttering: rr = radical right, c = conservative/Christian-democrats, l = liberals, g = greens, s = social democrats, rl = radical left; conservative/Christian-democrats in bold, deviant radical right parties in italic.

As we have seen, supporters of immigration tend to be in favor of quotas and against border controls, while opponents of immigration tend to be against quotas and in favor of border controls. The attitudinal divide clearly trumps the divide between member states, which again documents that the potential for further politicization has not yet been fully exploited by the political forces in Europe. The divide between member states is secondary to the attitudinal divide, which is reflected by the fact that each attitudinal camp is further divided into two groups of countries, with the eastern European supporters and opponents of immigration forming separate groups that are less favorable to the major policies than are western and southern Europeans. On the vertical dimension of the attitudinal space, which mostly represents the Dublin regulation, the opponents to immigration from the southern European frontline states form a separate cluster: They take a middling position on the main dimension, mainly because they are less opposed to relocation quotas than are opponents of immigration in other countries. At the same time, they are the group that is most opposed to the Dublin regulation. By contrast, those who oppose immigration in destination states like the UK, Germany, or Sweden are the groups most in favor of this regulation. Note that the second dimension does not contribute much to the structuring of the space in terms of immigration attitudes.

As for the combination of conflicts between partisan families with transnational conflicts, the dominant horizontal dimension is the same as in the previous graph, but the vertical dimension is not so much related to the Dublin regulation. Instead, it refers to aspects of border control that do not always go together with positions on quotas in some countries. On the horizontal dimension, in most of the countries, the radical right is opposed to the left (radical left, greens, and social democrats). Importantly, the radical right also includes the conservative parties in Hungary (Fidesz) and Poland (PiS). The conservative parties are marked in bold in the graph in order to show that they are spread considerably across the horizontal axis. While most of them are located in the middle of the space, with the Austrian conservatives closest to the cluster of the radical opponents of burden sharing, note that the German CDU as well as the Portuguese conservatives (together with some liberal parties) are part of the left cluster that favors burden sharing. As we already saw in Chapter 4 and as we shall see in the following chapter, the conservative/Christian-democratic parties have reacted quite differently to the refugee crisis in the different countries, which is reflected in their voters’ policy positions – as we can see here. On the other hand, the radical right in the two frontline states (Greece and Italy) is not part of the radical opponent cluster; rather, it is situated in the middle of the space, given that it is also rather favorable to quota schemes. On the vertical dimension, there are party families in some countries that differ with respect to the positions on border control – some oppose some aspects of border controls, while others generally support border controls. In the group opposing border controls, we find Portuguese parties across the entire spectrum and center left and center right parties from eastern Europe, while the group supporting border controls includes mainly right-wing parties from the frontline states and the UK but also the center left party from Greece and the German liberals.

Conclusion

In terms of transnational conflicts, we have found the expected opposition between the frontline states (Greece and Italy) on the one hand and the V4 countries (augmented by eastern European bystander states) on the other hand. The contrasting stance of the policymakers from these countries during the refugee crisis is reflected in their voters’ positions. Citizens from western European destination, transit, and bystander states generally take more moderate positions on the main dimension of conflict, which is defined by relocation policies. At the domestic level, we found the expected opposition between nationalists and cosmopolitans, which is politically articulated by the radical right and some nationalist-conservative parties on the one side and by the left and some parties of the mainstream right on the other side. We found that the same dimension structures the debate at the national and at the EU level. The domestic polarization appears to be more intense than the transnational one, especially in terms of immigration attitudes. When analyzing the combined transnational and domestic conflict configuration, this is reflected in the greater structuring capacity of domestic conflicts. Transnational conflicts appear as secondary to the domestic attitudinal conflicts, where they form a subdivision of the two attitudinal camps, and they are also secondary to the domestic partisan conflicts, where they divide the partisan camps with regard to some aspects of the border control policies. The transnational conflicts are ultimately rooted in the domestic conflict structure of the member states, where the opponents of immigration constitute the critical factor. In some key countries, they make up a plurality or even a majority of the population, which is mobilized by radical right and nationalist-conservative parties, depending on the country.

The implications for European policymakers in the domain of asylum policy are quite clear. The conflict potentials of immigration policies have not yet been fully mobilized. They are very large and have markedly increased in the destination states of northwestern Europe over the past few years. This means that policymakers are facing very strong constraints in terms of what is possible in this policy domain. As long as the critical underlying attitudinal potentials are not fully mobilized and as long as the parties mobilizing the opponents to immigration do not constitute the dominant coalition partner in government, joint solutions at the European level remain possible even in the most contested policy domains. However, when opponents to immigration become dominant in a given country and the parties mobilizing them become the dominant coalition partner or the exclusive governing party, as has been the case in Hungary and Poland (and other eastern European countries), the respective member states can legitimately prevent joint solutions, even if such solutions are supported by most of the other member states and, above all, by the frontline states. Given this state of affairs, relocation schemes do not appear to be a politically feasible option at the moment we collected our survey data (June-July 2021). The Dublin regulation benefits from the fact that even voters in the frontline states do not seem to be aware of what this policy exactly implies. However, voters in frontline states are well aware that their burden is not sufficiently shared by the other member states. Finally, the more restrictive policies of border control and externalization receive more support. Externalization policies are least contested.