Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Contributors

- Introduction

- I Little Britain's History of Slavery

- 1 From Guinea to Guernsey and Cornwall to the Caribbean: Recovering the History of Slavery in the Western English Channel

- 2 ‘There to sing the song of Moses’: John Jea's Methodism and Working-Class Attitudes to Slavery in Liverpool and Portsmouth, 1801–1817

- 3 Portrait of a Slave-Trading Family: The Staniforths of Liverpool

- 4 Forgotten Women: Anna Eliza Elletson and Absentee Slave Ownership

- 5 East Meets West: Exploring the Connections between Britain, the Caribbean and the East India Company, c. 1757–1857

- II Little Britain's Memory of Slavery

- Afterword

- Selected Bibliography

- Index

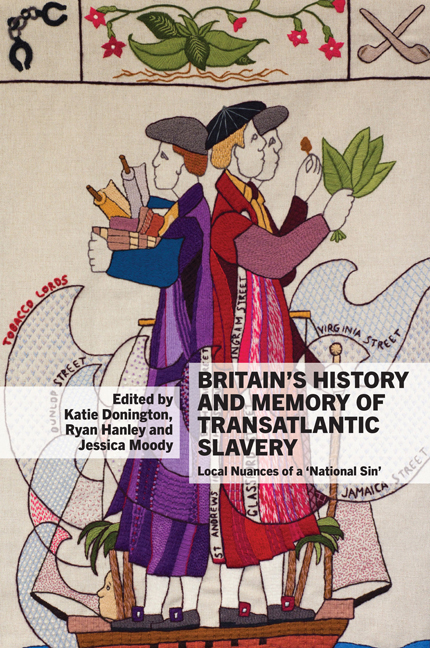

- Plate section

4 - Forgotten Women: Anna Eliza Elletson and Absentee Slave Ownership

from I - Little Britain's History of Slavery

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Contributors

- Introduction

- I Little Britain's History of Slavery

- 1 From Guinea to Guernsey and Cornwall to the Caribbean: Recovering the History of Slavery in the Western English Channel

- 2 ‘There to sing the song of Moses’: John Jea's Methodism and Working-Class Attitudes to Slavery in Liverpool and Portsmouth, 1801–1817

- 3 Portrait of a Slave-Trading Family: The Staniforths of Liverpool

- 4 Forgotten Women: Anna Eliza Elletson and Absentee Slave Ownership

- 5 East Meets West: Exploring the Connections between Britain, the Caribbean and the East India Company, c. 1757–1857

- II Little Britain's Memory of Slavery

- Afterword

- Selected Bibliography

- Index

- Plate section

Summary

Late eighteenth-century representations of the absentee slave owner depict a rich, ostentatious and often dissolute figure. Novels, plays and newspapers of the period presented caricatures of this West Indian ‘type.’ Passionate, haughty and extravagant, this figure, almost exclusively male, represented a particular kind of foppish masculinity. In his 1771 novel Humphry Clinker, Tobias Smollett vividly described these ‘planters, negro-drivers and hucksters’ as ‘men of low birth, and no breeding.’ Having ‘found themselves suddenly translated into a state of affluence unknown to former ages,’ he suggests that ‘their brains’ had been ‘intoxicated with pride, vanity, and presumption.’ Yet not only does this crude stereotype belie the extent to which many slave-holding men were able to successfully present themselves as polite and respectable gentlemen, it also fails to acknowledge that women, like Jamaican slave owner Anna Eliza Elletson, were actively involved in the slave-owning enterprise.

Although he portrayed the West Indian absentee as uncouth, self-indulgent and male, Smollett had himself married a Jamaican heiress and was economically reliant on remittances from the Caribbean. This was hardly uncommon in late eighteenth-century society. By the 1830s, when slavery was abolished in the British colonies, there were over 3,000 absentees living in metropolitan Britain and although it is difficult to discern concrete figures for the earlier period, rates of absenteeism grew exponentially as the eighteenth century progressed. Yet absentees were, as Douglas Hall has demonstrated, ‘a heterogenous lot.’ While returning to the metropole was an increasingly attractive proposition for those who had made their fortunes in the Caribbean, other British absentees had inherited plantations and slaves – or annuities and legacies secured on this property – or were mortgagees who had foreclosed on West Indian estates. Absentees, in all their diverse forms, occupied an increasingly prominent role in British society.

The West Indian colonies, and Jamaica in particular, lay at the heart of an imperial network reaching the zenith of its profit and prosperity. They were ‘shining Trophies […] extend[ing] the Fame, display[ing] the Power, and support[ing] the Commerce of Great Britain.’ The production of sugar was a huge industrial enterprise, underpinned by an exploited and enslaved workforce. As European sugar consumption rose, exports from the West Indies reached new heights.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Britain's History and Memory of Transatlantic SlaveryLocal Nuances of a 'National Sin', pp. 83 - 101Publisher: Liverpool University PressPrint publication year: 2016