In this chapter you will learn:

➤ Why it is normal to feel anxious during pregnancy and after having a baby

➤ How to recognise what happens when you feel anxious

➤ The principles of a cognitive-behavioural understanding of maternal anxiety that underpin this book

➤ Why anxiety in pregnancy and motherhood is important to address for mums and babies

Why Is It Normal to Feel Anxious During Pregnancy and After Having a Baby, and When Is It a Problem?

The time of pregnancy and after having a baby can be very positive and exciting, but we know that it can also be challenging in lots of ways and mental health difficulties are common during pregnancy and postnatally. Contrary to popular belief, the most prevalent problem is anxiety rather than depression. In fact, about 15% of women will experience a significant anxiety problem at some point during pregnancy or the first postnatal year [Reference Dennis, Falah-Hassani and Shiri1]. The high prevalence of anxiety during this time makes a lot of sense. The journey to, through and beyond pregnancy is paved with new experiences, uncertainty and unpredictability, all of which can generate or amplify feelings of anxiety. On top of this the stakes can feel especially high as you face new responsibilities of growing, birthing and caring for a baby. The general stress of sleep deprivation and physical, emotional and financial changes all play a role. Some women will adjust well to these new conditions, but for many others this process does not occur so readily. Anxiety is a normal emotion that is triggered in all of us from time to time, but an anxiety problem is said to occur when anxiety is excessive, persistent and interferes with aspects of your life.

Anxiety and feeling low often go hand in hand. Depression, a persistent feeling of low mood or loss of enjoyment in things, can make it hard to function. If you are experiencing depression or have been diagnosed with postnatal depression, this book could be useful to consider how the different stresses associated with pregnancy and becoming a parent are affecting you and what you can do about them. Many women we work with have low mood as a result of their anxiety problems, and getting on top of these can also help their mood lift. Sometimes this is not enough, and depression is a problem in its own right. More specific resources for treating depression are signposted at the end of this book.

What Is Anxiety?

Is my baby moving enough?

Will my baby be healthy?

Will I cope with the birth?

Will I be a good enough parent?

What will people think if he cries?

What if I drop her?

Just about every mother that has ever walked the planet has experienced anxious thoughts like these at some point. They aren’t pleasant or comfortable and they certainly aren’t spoken about enough, but they are a near universal part of pregnancy and parenthood. In fact, recent research has shown that 100% of new mothers experience intrusive, unwanted thoughts about something bad happening to their newborn in the first weeks after birth.

So, if you feel anxious, nervous or apprehensive in some way as a mum to be or a new mum, the first key message we want you to take away is you are not alone.

Of course, anxiety is not just a common aspect of motherhood but a normal part of being human and something most of us will be familiar with long before we begin our journey to being a parent. For example, when facing an exam, an important meeting or job interview, a big family occasion, public speaking or waking to hear a noise in the night. In certain circumstances, any of these situations could trigger a cascade of responses – body sensations, thoughts, images or memories that flash through our mind, feelings of fear and worry, alongside urges to respond in a certain way. We may not always be fully aware of all of them, but these quick, automatic signals have evolved over millions of years to help alert us to potential danger and ready our body for action to stay safe.

Our capacity for anxiety means we pay attention to danger, and this can be lifesaving – if this wasn’t the case we probably wouldn’t exist for very long and humans would have died out long ago! Consider the situation of crossing the road after meeting up with a friend. You hear the rev of an engine as you step out from the pavement. Without anxiety your brain wouldn’t get the signals it needs to surge adrenaline, switch on the ‘fight, flight or freeze’ response and instantly escape the threat – in this case pulling quickly back onto the curb.

In basic evolutionary terms we have two main tasks as humans: survival and reproduction. It is very likely then that this hard-wired anxiety has given us an evolutionary advantage as it has helped us survive being eaten by predators and reproduce successfully.

Key Idea

Anxiety is an essential part of being human that has enabled us to survive.

So, anxiety can be helpful, it has a purpose and has ensured the survival of our species. But unfortunately, it is not always accurate or useful. Any of us who have felt persistent anxiety will recognise it can also be unpleasant, uncomfortable and upsetting. It can stop us from doing the things we want to do and suck the fun out of life, including motherhood.

What Happens When We Feel Anxious?

Anxiety affects our minds, bodies, what grabs our attention and our behaviour. In this section we will consider this in more detail, so you can start to recognise the patterns that can occur.

An Anxious Mind

Our minds are rarely quiet – at any one time our thoughts might be full of words, pictures, memories from the past or a combination of some or all of these things. These might be positive, negative or neutral thoughts. Anxiety influences the content: when anxious, our minds typically churn up thoughts that are focused on negative things which might happen in the future – trying to predict if something ‘bad’ could happen, the worst-case scenarios, the potential danger ahead. We might have lots of ‘what if … ’ type thoughts, frightening images or memories of bad things that have happened to us. Our anxious mind can feel like a spotlight shining a light on our deepest fears, the problems we are facing now or in the future, or the potential danger around us.

Our relationships with others are also really important, so we are also sensitive to social threats. Anxious thoughts can also be judgements about ourselves, worries about what others are thinking, doubts about what we have or haven’t done, or urges telling us what we ‘should’ or ‘must’ do thrown in for good measure. All of these ‘thoughts’ are quick fire, automatic and can leave us feeling worried, stressed, panicked, fearful or with a sense of dread. To make things worse, once we start feeling anxious, we are more likely to read into ambiguous or neutral situations as threatening or dangerous.

It would be impossible to list all the anxious thoughts that can occur, but here are some common ones women have talked about with us in pregnancy and after birth:

Thoughts

My baby isn’t safe

My baby isn’t moving enough

I won’t cope with the birth

What if I am not a good enough parent?

What if she chokes?

What if I drop the baby?

What if that toy isn’t clean?

Images

Judgements

Doubts

Urges

Anxiety will draw you into the content of the thought, but if you spend some time observing how your mind works when you feel anxious, you might also start to notice certain patterns or ‘styles’ in your thinking that aren’t helping you to feel better. Some common patterns that are often linked to many forms of anxiety in the perinatal period are listed in the following section.

‘Thinking the Worst’

Your anxious mind might jump to the worst-case scenario even though the initial problem or situation you are facing is quite small. This might be in the form of a verbal thought, e.g. a pain in your groin might trigger the thought ‘The pain of childbirth will be unbearable’, or you might spot an image or ‘flash forward’ to a future feared outcome. These attention-grabbing thoughts can elbow all the other possibilities out of the way.

‘All or Nothing’ or ‘Black and White’ Thinking

Here we mean a tendency to think in extremes, e.g. ‘If it is not 100% right then I have failed’; ‘I am either completely safe or in total danger’; ‘if things are uncertain then they will go wrong’; ‘if I don’t achieve a vaginal birth then I am a total failure as a mother’. Anxiety can mean we take an overly rigid view of a situation that then gets in the way of seeing how the world really works – i.e. that there are often many shades of grey and life operates on a continuum rather than in extremes.

‘Shoulds’ and ‘Musts’

Here we mean putting unreasonable (sometimes impossible) expectations or demands on yourself (or others), e.g. ‘I should feel nothing but positive feelings about the prospect of motherhood’; ‘I must eliminate all risk’; ‘I shouldn’t feel this overwhelmed – there must be something wrong with me’. This style of thinking is common amongst people who have a general tendency to set themselves high standards or strive for perfection. Unsurprisingly it leads to feelings of stress and pressure and of course self-criticism when you fail to meet the standard.

Rumination or ‘Post-mortems’

When you are anxious, it is natural to look for or spot evidence that fits with how you are feeling. This can mean churning over past experiences and conversations around pregnancy, birth or events that confirm to us we are in danger or we (or others) aren’t capable or competent enough to ensure a positive outcome. This process naturally turns the temperature up on anxiety because it means we end up with rather ‘tunnel vision’ and only pay attention to a limited part of the picture.

Worry

By worry we mean the process of repeated negative thinking, usually in the form of sentences that start with ‘What if … ’. You might be trying to feel more in control by running through various possibilities to ‘plan for the worst’ or you might feel that worrying in advance helps you to prevent something bad from happening or find solutions to problems. Alternatively, you might feel that worry controls you and there is nothing you can do to manage it. The tricky thing is that the more you engage in the process of churning worries in your mind, the more anxious you will feel. Worry itself doesn’t solve problems or create more certainty or control – in fact it usually only fuels more doubt and discomfort.

Magical Thinking

Sometimes we might think of this as ‘superstitious thinking’ or a tendency to see two unrelated events as directly linked. This type of thinking is influenced by culture and society, but it is found in some form in all of them. In pregnancy, the idea of ‘tempting fate’ is a good example: you might think that by doing something, e.g. talking about your pregnancy before 12 weeks or buying things for your baby is ‘risky’ and that something bad might happen to the baby. The unfortunate reality is you can’t eliminate risk in this way. Trying to do so often drives up anxiety as it keeps you focused on negative outcomes.

Emotional Reasoning

This is the idea that because we feel anxious, there must be something to be anxious about. However, sometimes, such as in the case of phobias for example, our threat system is activated when there is no threat, so this reasoning is very circular.

An Anxious Body

Anxiety is very physical. It is the body’s alarm system and it is very effective. A stress response is triggered when we perceive a threat, and parts of our brain and a part of our nervous system called the ‘sympathetic’ or ‘autonomic’ nervous system kick into gear. When this happens, a brain structure called the amygdala sends signals to another part of our brain – the hypothalamus. This in turn sends signals to the pituitary gland which sits just below it in the brain. The pituitary gland releases a hormone telling our adrenal glands (which sit just above our kidneys) to release a flood of the hormones adrenaline, noradrenaline and cortisol into the body. This chain reaction is sometimes called your ‘fight, flight or freeze’ response. It is through the release of these hormones that rapid physical responses in the body occur, designed to help us protect ourselves. These are automatic and outside of our control. They are harmless but can feel very uncomfortable and sometimes frightening. Almost every organ in our body is affected.

Heart rate, breathing and blood pressure increase. This means we can move oxygen and other nutrients more quickly to our muscles and brain so we are able to face the danger or run away quickly. Our brains also prioritise survival functions. Blood is redirected from non-essential organs like our gut to our muscles, brain and heart. Feeling sick, having ‘butterflies’ in your tummy, appearing pale or flushed, feeling cold and clammy or hot and sweaty are all a result of this shift in blood flow. Our senses sharpen so we are in tune with our surroundings and vigilant for threat – for example our pupils dilate to take in more light so we can see clearly but this might mean we feel jumpy and on edge and it can be hard to concentrate on anything but the danger we perceive. Our muscles also tighten, leaving us tense and restless. Have a look at the table below for some more examples.

The tricky thing is this alarm system is so efficient it kicks in when we face real danger but also when we think there is a danger (but there actually isn’t). If you think of what it’s like to watch a horror film or go on a roller coaster, you may recognise some of the sensations too. Think of it a bit like a faulty smoke alarm going off repeatedly even if there is no fire, for example when you burn toast or light a match. When that alarm is blaring it is hard to concentrate on what is actually happening and realise there is no real threat.

Anxious Reactions: Trying to Feel Safer

The point of anxiety is that it isn’t pleasant and gets us to do things to try and resolve it. Naturally, we might feel pulled into action to try and feel safer and more in control. Our responses can include things we actively do, e.g. avoid, escape, check, seek reassurance, as well as things we try to do in our heads to feel better, e.g. churn over all potential scenarios or ‘what ifs’, ruminate, think positively, argue with ourselves and so on. They all have a purpose, but as we will discuss in detail throughout the book, can be counterproductive. Below are some examples of common ‘safety-seeking strategies’ you might adopt when you are feeling anxious.

Key idea

Anxiety affects our whole bodies, including what we think, feel and do.

Making Sense of Anxiety: A Cognitive-Behavioural Approach

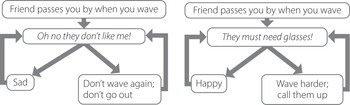

Cognitive-behavioural theory is based on the idea that it’s not just what happens in a particular situation, but what we make of it that affects how we feel and what we do. For example, if you say hello to a friend on the opposite side of the road and they walk on without waving back – you may think a number of things, including: ‘Oh they didn’t see me!’, to ‘Oh no, they don’t like me’, to ‘Oh dear, they really need some glasses.’ Each of these interpretations will connect with different moods and reactions.

As you can see from this example, there are usually a number of possible ways to interpret an event, even when the event is very negative or even very positive; for example, experiencing a flashback of a road traffic accident and thinking ‘I’m still thinking about this because I’m weak’, or being at a very nice birthday party and thinking ‘I’m not connecting with people even here because I’m weird’. The interpretation that most readily comes to mind is likely to be influenced by other experiences you have had, and your underlying beliefs about the world, yourself or other people. This explains why two people can experience similar events but have very different responses in terms of emotion and behaviour.

The responses themselves also play a very important role in the development of anxiety problems and what keeps them going. For example, considering the example of seeing your friend across the road, you may wave more vigorously at people the next time to make sure they see you, or alternatively decide not to wave at anyone again to avoid further perceived rejection. Each of these behaviours will in turn influence to some degree what then happens, and your further interpretations of the situation, including what you believe about yourself and others.

The Perinatal Anxiety ‘Equation’

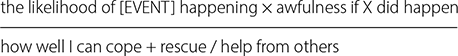

Furthermore, anxiety is linked to our interpretations in particular ways. The severity of the anxiety you are experiencing will be a product of not just how likely you think something is, but how awful it would be for you personally if it happened, and how able you think you will be to cope with it, including whether you might get help from others.

Severity of anxiety about [EVENT] is proportional to:

So even though we may realise something is not very likely, our anxiety is multiplied many times by our focus on how awful and difficult it would be if it did come true. This idea is relevant to all the anxiety problems we work with and explains why, when people give lots of reassurance, or people are told they need to try to ‘be rational’, it just doesn’t work. Anxiety is an emotional problem. Pregnancy and birth are times of increased vulnerability to anxiety because there are all the key elements of any anxiety problem at a time of a very real increase in responsibility and uncertainty, lots of life changes as well as other stressors. It can really feel like it’s all on you to resolve and solve all the issues related to the physical and mental health of your baby.

The important point is that, whilst these interpretations are usually very understandable, they may not be accurate, and they are changeable. You will learn a lot more about how to evaluate and challenge these ideas in relation to specific types of anxiety in the rest of this book.

Why Is Anxiety Important to Address in Pregnancy and Early Parenthood?

Excessive anxiety is, as you know, a horrible problem to have, at best taking the fun out of life but often taking away much more than that. Pregnancy and the postnatal period is of course very different to other times of life and it is normal to feel more risk-averse, vulnerable and careful. Even though the concept of ‘normal’ behaviour may be slightly different, it doesn’t mean that you have to take excessive precautions relative to other women. Doing this can be highly stressful and impair your experience of pregnancy, birth and motherhood.

‘Now’ is always a good time to do something about it if you have an anxiety problem, but as you enter this new phase of life, making changes is likely not only to benefit you, but also those around you, including your baby. Being pregnant or a new mum means learning a lot of new skills and ways of being, so it is actually a particularly good time to tackle anxiety.

Is Anxiety Harmful for My Unborn Baby?

It is clear that the main person who is affected by anxiety is the person who is in the middle of it. Some studies of huge groups of women have highlighted a link between antenatal anxiety and stress and a raised chance of outcomes such as lower birth weight, earlier births or increases in emotional difficulties in children. This may sound frightening or upsetting but there are several important things to bear in mind – the overall rates of these things are relatively low [Reference Dennis, Falah-Hassani and Shiri1]. The vast majority of mothers experiencing anxiety problems or any other issues or no anxiety do not have these outcomes. Often women coming to our clinics have heard or are told about these studies and pick up the message that they are somehow harming their baby just by being anxious, unfortunately leading to lots more worry for some. Remember that worrying and anxiety to some degree is very normal and unavoidable and of course helpful in some circumstances. The best any of us can do in pregnancy and beyond is to try and take care of ourselves and work on excessive anxiety. Doing this will have a big influence on your well-being and by extension theirs.

Is it Safe to Tackle Anxiety in Pregnancy?

Ironically, sometimes there are also unhelpful messages related to actually tackling anxiety in pregnancy. Pregnancy is a good time to tackle anxiety and the principles are just the same as outside this time. This involves first getting a good understanding, then applying this by testing things out and getting new knowledge and experiences. This process is sometimes called exposure, as you are ‘exposing’ yourself to your fears. A term we prefer and use in this book is behavioural experiments, or ‘testing things out’, because you are generally taking an informed approach to what you are testing out and why. Of course, doing something you have previously avoided may be a little anxiety-provoking at first, but this generally subsides. The experiments are not about going into extreme situations, but are about doing things that the average pregnant woman would do.

We are aware that occasionally women are told (sometimes by health professionals not trained in how to help people overcome anxiety), that doing exposure that could make them feel anxious during pregnancy could be harmful to their baby. This is not founded on evidence and is a good example of how the system around people can feed into the things that keep anxiety going. It rather misses the point that people are doing the exposure because they are already anxious! Secondly, although exposure tasks might initially raise anxiety, this quickly reduces and there is very good evidence that these kinds of exposure experiments lead to overall improvements in anxiety as people find out how the world really works and acclimatise to this new way of doing things, which is very much the idea of this approach [Reference Arch, Dimidjian and Chessick2].

We can therefore assume that working on anxiety can only help both mother and baby.

To Sum Up

Anxiety itself is not dangerous even though it can make you feel in danger

Anxiety makes pregnancy and being a parent even harder than it is already

Anxious feelings occur at the same time as thoughts, doubts or images about bad things happening

You can identify and change your anxiety-related thinking and the ways of managing anxiety which might not be helping you to feel better

You can change how anxious you feel