Summary

Men were fascinated by curves and curved shapes long before they regarded them as mathematical objects. For evidence one has only to look at the ornaments in the form of waves and spirals on prehistoric pottery, or the magnificent systems of folds in the drapery of Greek or Gothic statues. It was the Greek geometers who began to study geometrically defined curves as, for instance, the contour of the intersection of a plane with a cone, or the locus of points reached one by one through a geometrical construction. The straight line and the circle could be drawn with very primitive instruments in one continuous movement, and so they were distinguished as ‘plane’ loci from the ‘solid’ conic sections. All other curves were loci lineares, i.e. just ‘lines’, ‘curves’. Some curves were generated by the movement of mechanical linkages, or at least were imagined to be so generated: the spirals of Archimedes were of that type. A classification into ‘geometrical’ and ‘mechanical’ curves (which does not quite correspond to the modern use of those terms) became fixed when analytical geometry, in the seventeenth century, made it possible to distinguish with precision what we should now (following Leibniz) call algebraic and transcendental curves.

In his search for the true shape of a planetary orbit Kepler tried a variety of curves before he found that the ellipse gave the best fit.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

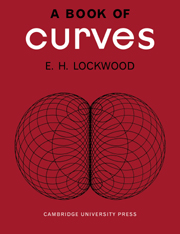

- Book of Curves , pp. ix - xPublisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 1961