Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Foreword

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Tribute to Charles-Marie Widor

- Part One Studies, Early Performances, and Aristide Cavaillé-Coll (1844–69)

- Part Two La Belle Époque: The Franco-Prussian War to The Great War (1870–1914)

- Part Three The Great War and Important Initiatives (1914–37)

- Appendix 1 Birth record of Charles-Marie Widor, 1844

- Appendix 2 Widor’s Diplôme de Bachelier ès Lettres, 1863

- Appendix 3 Widor’s letter of appreciation to Jacques Lemmens, 1863

- Appendix 4 Brussels Ducal Palace organ specification, 1861

- Appendix 5 Widor’s certificate for Chevalier de l’Ordre du Christ, 1866

- Appendix 6 “To Budapest,” 1893

- Appendix 7 Widor’s travels to Russia and his 1903 passport

- Appendix 8 Widor’s list of his works in 1894

- Appendix 9 The Paris Conservatory organs, 1872

- Appendix 10 Chronique [Widor’s appeal for an organ hall at the Paris Conservatory, 1895]

- Appendix 11 Widor’s certificate for the Académie Royale, Brussels, 1908

- Appendix 12 “Debussy & Rodin,” 1927

- Appendix 13 The American Conservatory organ, Fontainebleau, 1925

- Appendix 14 Letters concerning the Trocadéro organ restoration, 1926

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

- Eastman Studies in Music

40 - The Dauphin’s organ

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 09 May 2024

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Foreword

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

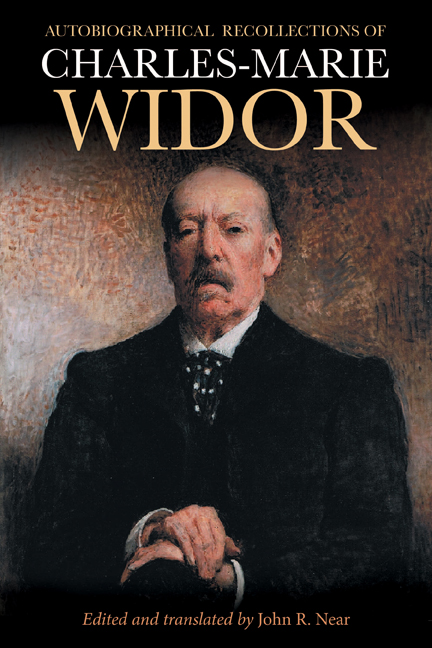

- Introduction: Tribute to Charles-Marie Widor

- Part One Studies, Early Performances, and Aristide Cavaillé-Coll (1844–69)

- Part Two La Belle Époque: The Franco-Prussian War to The Great War (1870–1914)

- Part Three The Great War and Important Initiatives (1914–37)

- Appendix 1 Birth record of Charles-Marie Widor, 1844

- Appendix 2 Widor’s Diplôme de Bachelier ès Lettres, 1863

- Appendix 3 Widor’s letter of appreciation to Jacques Lemmens, 1863

- Appendix 4 Brussels Ducal Palace organ specification, 1861

- Appendix 5 Widor’s certificate for Chevalier de l’Ordre du Christ, 1866

- Appendix 6 “To Budapest,” 1893

- Appendix 7 Widor’s travels to Russia and his 1903 passport

- Appendix 8 Widor’s list of his works in 1894

- Appendix 9 The Paris Conservatory organs, 1872

- Appendix 10 Chronique [Widor’s appeal for an organ hall at the Paris Conservatory, 1895]

- Appendix 11 Widor’s certificate for the Académie Royale, Brussels, 1908

- Appendix 12 “Debussy & Rodin,” 1927

- Appendix 13 The American Conservatory organ, Fontainebleau, 1925

- Appendix 14 Letters concerning the Trocadéro organ restoration, 1926

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

- Eastman Studies in Music

Summary

By March 28, 1918, Big Bertha had been thundering for five days. The Duke of Alba was supposed to come and talk to me about the exhibition. I rushed to his house to tell him that it was dangerous to go out. It was Easter Sunday. From fear of the danger threatening the crowd, the services of Saint-Sulpice had been reduced to a minimum. The very simple evening service lasted only fifteen minutes. For their relative safety, the clergy had set up a dormitory in the vaulted room of the façade—located between the two towers—in which was located the Dauphin's organ that I have talked about elsewhere because of incidents surrounding its history. When the dormitory was removed from this room, which was poorly protected by the windows and not heated, I went to find the parish priest to obtain permission to have the organ moved to prevent it from getting moldy. I had it placed in the Chapelle du Péristyle, which is heated like all the rest of the church. This was done within six months.

The Dauphin's organ is an interesting document because of the limited range of its keyboards, its particular sonorities, and the style of the time. Once a week, Marie Josèphe of Saxony had her musical evening with organ, the Dauphin and their daughters as an audience, and sometimes a singer and a guest, never more than two. Jean-François Marmontel tells in his Mémoires of an invitation to dine at the Dauphin's in strict privacy. The Dauphin and his wife did not say a word, and Marmontel was forced into a monologue during the whole dinner. But the next day he received a visit from an aide-de-camp of the Dauphin who came to apologize for the silence of his masters. He related, “Marmontel's conversation had interested them so much that they had not dared say a word.” He had noticed some unusual movement of the table, wondering what it meant. It was apparently the Dauphin who expressed his delight at hearing Marmontel by giving a kick to the table, as if to say: “Isn't this all charming?”

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2024