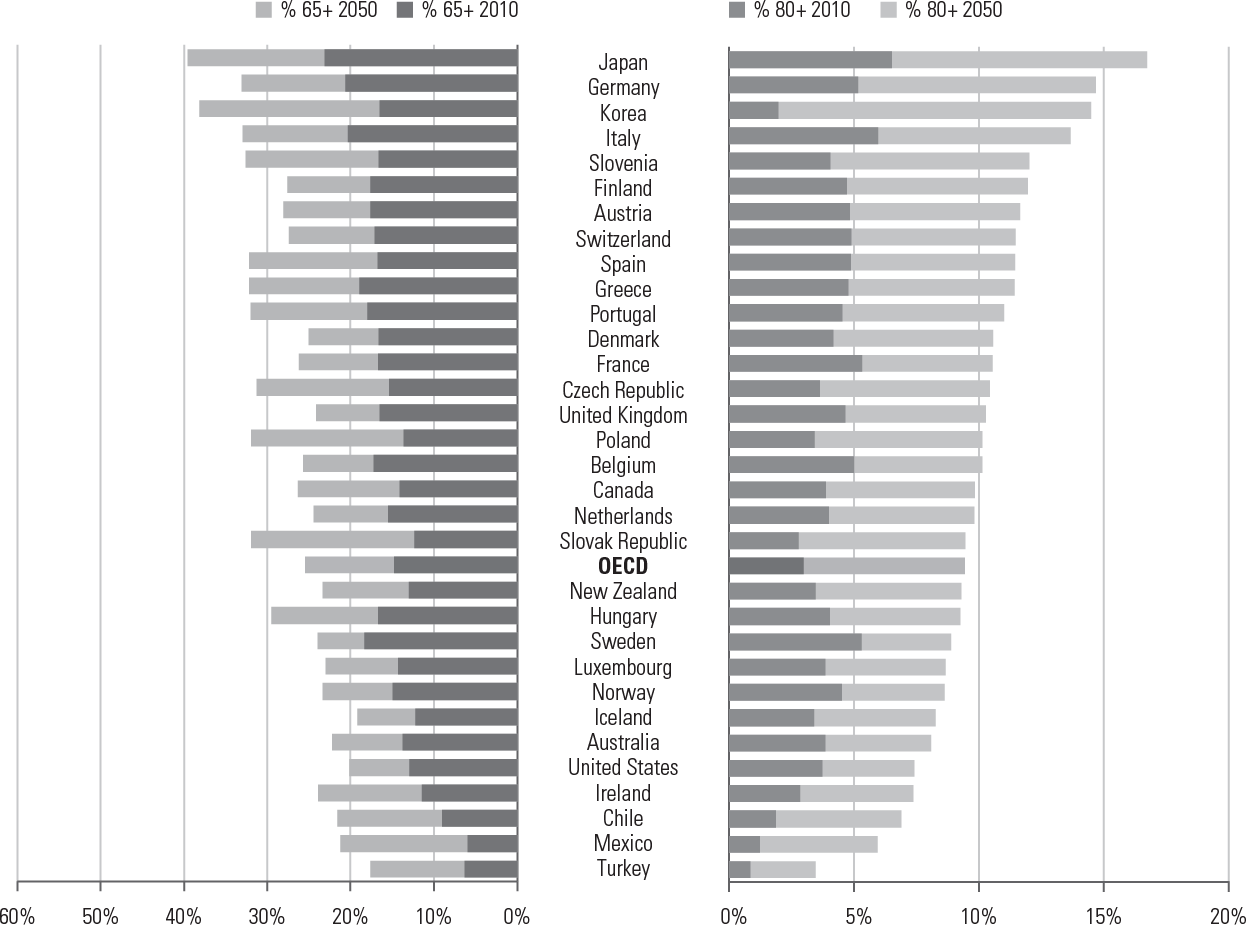

Life in an ageing society is a truly novel experience. For most of our species’ history, a large majority of people were young and life much beyond 60 seemingly a rarity (Reference ThaneThane, 2005). Now, populations around the world are ageing. It might be happening in countries at different speeds and to varying extents, but it is an almost universal phenomenon. In 2000 the median age in Western Europe was 37.7; in 2020 the median age was 42.5. By 2050 it will rise to 47.1 (UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2020). Looking at specific Western European countries, this trend becomes even more impressive. In Italy the median age in 2000 was 40.3, in 2020 it was 47.3 and by 2050 it will be 53.6. Spain follows a similar pattern, with a median age of 37.6 in 2000, 44.9 in 2020 and a projection of 53.2 for 2050 (Statsita, 2020). Figure 1.1 shows us by how much the population is expected to age, looking at over 65 year olds in 2010 and 2050 as a share of the total population and comparing that with over 85 year olds in 2010 and 2050.

Figure 1.1 The shares of the population aged over 65 and 80 years in the OECD will increase significantly by 2050

The fact that societies are ageing is a good news story. If the twentieth century were a movie, this would be a balmy last scene, with the protagonists ageing in health and peace after a very difficult adventure. It is a story of increased wealth, better health and improved human welfare around the world.

Ageing of the population occurs for a number of reasons. People are by and large living longer than ever before. The average European born in 1950 could expect to live for 62 years based on the death rates at that time. Since then, the life expectancy of subsequent cohorts has mostly trended upwards. A European born in 2019 could expect to live for 78.6 years (Reference Roser, Ortiz-Ospina and RitchieRoser et al., 2019). These increases in longevity have occurred because health conditions that in previous years were a death sentence are no longer so threatening. Infant and child mortality rates, in particular, have fallen dramatically. This matters because a large part of average low life expectancies is due to childhood infectious diseases; life expectancy at age 1 has generally been higher than life expectancy at birth. The fact that life expectancy at birth in the WHO European region was 77.1 years and life expectancy at 1 was a marginally higher 77.3 years in 2015 is a sign of massive success in prenatal, perinatal and child health. Adults also have higher survival rates. To put this in perspective, consider that instead of dying at age 65 from an acute myocardial infarction thirty years ago, the same person today might survive the age 65 heart attack and eventually die of heart failure at 85.

On top of reduced mortality, fertility rates have also declined substantially, so that the average woman in 2020 was having 1.62 children, compared to 2.66 children in 1950 (UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2020). Greater legal, economic and social equality for women, hard-fought policy and legal changes that increase women’s reproductive autonomy, technological advances in birth control and changing expectations of life-courses all combined to reduce both desired and real fertility almost everywhere in the world. Much of the rich world has fertility below the replacement rate, presaging population decline and sparking worries.

The end result is an increase in survival and a decline in replacement. These two processes are leading to a slowly increasing population ‘bulge’ at older ages. While children up to the age of 17 comprise 19 per cent of the population in 2020 and are expected to make up 17.5 per cent of the population in 2050, the share of the total population in Western Europe over age 65 will increase from 19 per cent in 2020 to 28 per cent in 2050. For those above 85 years, their share of the population will increase from 2.5 per cent in 2020 to 5.6 per cent in 2050 (UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2020). Figure 1.2 shows this in graphic form. For most of human history, populations looked like Niger: a pyramid. Rich societies began to develop an urn shape after, roughly, World War Two, with a big bulge in the middle (the Baby Boom generation), more older people and fewer children. Throughout this book, the terms ‘older adults’ or ‘older persons’ will be used to refer to persons above the age of 65 unless otherwise specified. The reason these terms were chosen as opposed to ‘elderly’ or ‘senior’ is because they acknowledge the relativity of ageing (Reference TaylorTaylor, 2011) as the ageing experience can vary and does so from person to person.

Some countries’ populations are expected to shrink in the coming years, if they are not already in the process of shrinking; for example, Belarus, Bulgaria, China (and Taiwan, China), Croatia, Cuba, Czechia, Estonia, Germany, Greece, Italy, Japan, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, the Russian Federation, Slovakia, Slovenia, South Korea, Spain, Sri Lanka and Thailand. While in some cases, notably in Central and Eastern Europe, outmigration is part of the problem, it is not the only reason and nevertheless leaves behind demographic structures that are unusual in world history.

At face value one would think that the fact that populations are ageing should be celebrated. It reflects a range of successes in health care, from reproductive health to geriatric health, but also successes in social policy more broadly. People are living longer and enjoying all the life experiences that come with that.

For some, though, these developments point to worry rather than celebration. Many writers view population ageing as a threat to societies, governments and economies. They see rising health care, long-term care and pension costs. They see a large older population retiring en masse, depriving labour markets of productive workers and leaving governments with fewer revenues generated through taxation. And they see too few young people to compensate for these declines. In their darker versions, they see entire societies becoming decadent and dying, and perhaps perishing in geopolitical competition as a result. They posit a win-lose scenario for politics and policy, in which one generation’s gain is another one’s loss.

These fears need not come true. They are, rather, ‘zombie ideas’, policy or political ideas which persist in debates despite multiple empirical refutations (Reference QuigginQuiggin, 2010). As the rest of this introductory chapter argues, there is extensive research arguing that population ageing need not be a threat to the sustainability of states or their health care systems. As Chapters 2 and 3 show, there is not even much evidence that people who share an age share much else. Nor need there be a tradeoff between the interests of people of different ages. Rather, what we refer to throughout this book as ‘win-win’ solutions are possible. These are policies which do not create a political divide between people of different ages or generations, but rather those which invest over the life-course in order to maximize people’s health and wellbeing. The question that matters, and which the rest of the book explores, is why win-win policies are, or are not, adopted.

1.1 Two Very Different Narratives Depicting Ageing Societies

There are effectively two simple and in fact oversimplified narratives about older people in today’s society. The first is that older people are a forgotten and neglected group. They are pushed out of formal employment because of views that younger people are more productive. For reasons that largely have to do with the design (or lack thereof) of social welfare systems, they are overwhelmingly poor, lack good access to health care and live in low-quality housing. Perhaps the lack of public support afforded to them is due to concerns that expanding the welfare state would be untenable and unsustainable. And so, older people are left to suffer. This has been historically common. Societies with low poverty among older people are essentially a creation of the postwar welfare state, and they are not the norm (still rarer are the ones, notably the United States, where the elderly are less likely to be indigent than the working-age population). In Europe we can see a version of this forgotten-elderly model in Central and Eastern Europe, where healthy-looking fiscal balances can rest partly on very limited old-age security. Some societies effectively counterbalance poverty among older people with inter-family transfers (e.g. a parent who lives with adult children and might give or receive unpaid care), but reliance on strong and generous families in modern European societies is not obviously sustainable and is clearly not an adequate basis for policy in many of them.

It is also easy to find examples of ageism and age-related discrimination even in countries where public policies ensure an adequate material standard of living for older people. Care homes for older people were, for example, common COVID-19 hotspots, with terrible consequences in many places. Policies for transitions in and out of COVID-19 lockdown often blithely told ‘vulnerable individuals’ to stay home while reopening businesses and institutions – a sign that policymakers often failed to understand not just transmission mechanisms but also the important role older people play as employees, customers and unpaid workers in areas such as child care. A few politicians, such as the Lieutenant Governor of Texas (the state’s most powerful executive position) even went so far as to say explicitly that older people should be sacrificed ‘As a senior citizen, are you willing to take a chance on your survival in exchange for keeping the America that all America loves for your children and grandchildren?’ Patrick said. ‘And if that’s the exchange, I’m all in’ (Reference SonmezSonmez, 2020). for the greater good. Outside such stark reminders of the value that societies often place on older people’s lives, the evidence for age discrimination in areas from built environment to employment decisions is impressive (Center for Ageing Better, 2020; Reference Chang, Kannoth and LevyChang et al., 2020).

The second narrative, which is much better represented in international policy debates and the politics of some countries such as the UK and US, is that older people are primarily an entitled group. They are mostly Baby Boomers (those born just after World War Two) and as such have experienced substantial economic growth over their lifetime. They have good, steady, well-paying jobs even while youth unemployment skyrockets. They own property and other assets at a time in history when asset prices have reached historic highs. But their children or grandchildren’s generations are not, or should expect not to be, nearly as prosperous as them. A recent report published by the Resolution Foundation (Reference Bangham, Gardiner and RahmanBangham et al., 2019) about the UK argued that it can no longer be taken for granted that every generation will do better than the last. This is neither a surprising nor an ubiquitous trend, though; policies that lead to increasing income and wealth inequality over time should be expected to have a different effect over cohorts, with people who lived under more egalitarian political economies retaining advantages relative to the people whose lives were more clearly shaped by increasing inequality. In other words, boomers mostly spent their lives in more egalitarian times than Millennials, and so Millennials feel the effects of inequality more acutely.

It is easy to find the second narrative in the media, whether it is contributions to the endless overstated complaints about younger and older people’s consumption preferences and norms, or more putatively sophisticated analyses of social change in ageing society. In 2002 a writer in the Independent claimed that ‘of all the threats to human society, including war, disease and natural disaster, the ageing of the human population outranks them all’ (Reference LaurenceLaurence, 2002). The basis for this extraordinary claim was that every area of life, including economic growth, labour markets, taxation, the transfer of property, health, family composition, housing and migration will be impacted by the ‘demographic agequake’. A 2016 Time article (Reference BuchholzBuchholz, 2016) presented two big threats that an ageing population poses. The first is that the number of workers supporting retirees will significantly decrease. In the 1950s there were fifteen workers for every one retiree, while today there are about two workers for every one retiree. The second threat, particularly looking at the United States, is the need for more workers. Hospital employees and restaurant waiters are positions that need to be filled and are often done so by immigrants. The author argues that immigrants can fragment a country’s culture unless strong cultural and civic institutions are in place, suggesting that American traditions like hot dog cook-outs and Memorial Day parades could disappear. A 2019 piece (Reference PettingerPettinger, 2019) highlights the effects of an ageing population. The dependency ratio will increase, the government will spend more on health care and pensions, those people working will have to pay higher taxes, there will not be enough workers to cover all the work that needs to be done, the economy will change with more companies focusing on retirees as clients and increased pension savings could reduce capital investment. Rather than go on with examples from the pundit class, it might be more entertaining to look at witty tweets that make the same arguments.

These are all examples of the ‘greedy geezer’, image a phrase that a British journalist coined for the United States (dropping the adjective ‘old’ that would normally accompany ‘geezer’ but retaining all of the insult). Its policy theory is that older adults have it too good and that younger people will, overall, lose out as a result. Its political theory is that older people vote for politicians who help them to hold on to their wealth and preserve only those public sector entitlements and regulations, like pensions, early retirement ages and good access to health care that disproportionately benefit them, while raising taxes and debt and cutting expenditures on other age groups. Even if their intentions are good, older voters and the older politicians they elect just might not understand what younger people face, want or need (a point for which there is evidence from Japan (Reference McCleanMcClean, 2019).

Most readers might have been nodding along with one or both of these narratives. World literature abounds in stories of lonely and poor older people, for the good reason that old-age security is a relatively new and far from universal phenomenon. Punditry, and for that matter serious policy debate, frequently invokes the opposite stereotypes – of healthy pensioners enjoying a poolside drink in Mallorca financed by a generous welfare state that their children will never see. Some of us, including the authors in this project, had also nodded along at such stories, laughed at quips about gerontocracy or ‘OK boomer’, and drawn implications from the pronounced correlations between age and partisan votes. But research, including that of the European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies’ Economics of Healthy and Active Ageing series (of which this book is a part), showed us just how faulty, and pernicious, those stories are (to summarize the book very simply: Chapters 3 and 4 show how faulty they are; Chapters 5 and 6, how pernicious).

To understand the politics of ageing and health, and to get to win-win policies, requires recognition of not just how flawed these narratives are but how little power age has as an explanatory category in politics. This book is a work of interdisciplinary social science, but one about a topic where everybody has some experience and can understand, from multiple angles, the different decisions people make. Those decisions are diverse: whether it is parents who work to give their children a nice inheritance, children who leave work to care for parents, grandparents whose caring work permits their children to work, or just parents who do their best to introduce their child to people who might give them a good job. Generations and cohorts are made up of people with different ideas, assets and strategies. That fact, rather than stylized ideas about how entire generations behave, is the right starting point and one that gives us a sense of what age can explain about the treatment of older people in health, and its limitations as an explanation.

1.2 What Are the Consequences of Seeing Population Ageing in a Negative Light?

Perhaps above all else, the catastrophist narrative of population ageing provides someone to blame for other people’s problems. The lump of labour fallacy, which says (incorrectly) that there is a fixed amount of jobs, resonates with younger people struggling with high youth unemployment. As of January 2020, before the COVID-19 crisis, countries like Greece, Spain and Italy topped the European youth unemployment rates with 36.1 per cent, 30.6 per cent and 29.3 per cent respectively. Surprisingly, Sweden followed in fourth place with 20.6 per cent. Due to these percentages, people argue, erroneously, that the reasons for a lack of jobs are because too many older people have well-paying jobs and that the only solution is to force older people into retirement, even if they remain highly qualified, productive and willing to work. Every junior academic who wills the retirement of senior professors in the hope that it will create more junior posts is falling into the lump of labour fallacy.

In addition, organizations such as the International Monetary Fund or the World Bank present population ageing as a ruinous societal occurrence or a demographic ‘crisis’ that will not only threaten the welfare of older people but also that of children and grandchildren who are left with the task of providing for older people. In some countries this has been taken as evidence that the welfare state will become unsustainable given the expected increased cost of health and long-term care coupled with the comparatively small number of working adults, while in others that the welfare state has been turned to serve the interests of older people at the expense of the young, wrongly assuming that older people become dependent on society after reaching a certain age. The result is the increasing belief that politicians tend to promote short-term benefits for older people at the expense of long-term social investment due to intense political pressure imposed by older voters. Younger generation voters are assuming that older people are of the ‘selfish generation’ as they have been able to tailor welfare spending to meet their own needs at the expense of future generations.

More than anything, the ‘blame older people’ narrative provides a potential justification for scaling back the welfare state. If populations are ageing, with inevitable consequences, some will view the only solution is to tear down the welfare state. Cutting back on public services (and therefore individualizing burdens) will reduce future public debt. Spending nothing is the most superficial route to fiscal sustainability, even if it comes with a host of undesirable effects on well-being, equity and society overall (Reference CooperCooper, 2021 analyses the politicial origins of this argument).

Shifting from the arithmetic of intergenerational public transfers to broader theories that impute shared orientations to generations, we find more opportunities to pit generation against generation. It is not hard to find media, particularly from the USA and the UK, in which older people are roundly blamed for anything from climate change to Trump to Brexit.

The rhetoric of intergenerational conflict produces two related narratives. The first narrative assumes that ageing will bankrupt the welfare state. The Baby Boomers are getting older, living longer and profiting from a welfare state supported by a younger generation that will likely end up seeing very little benefit from the welfare system they are currently and heavily paying into. The second narrative assumes that older people hold a proportionately high amount of political power that they use to influence policymakers so that policies are passed in their favour. Since older people are deserving, seeing as they effectively built up the welfare state, society over-caters to them through heavy investment at the expense of younger generations. Both of these narratives end in the same place: cuts. The first leads to cuts through the implementation of austerity measures, thereby cutting welfare benefits for both older people and younger generations, while the second narrative leads to cuts for future generations as all the available welfare money goes to serving the needs of the elderly, thereby effectively leaving younger generations without certain benefits. Both create an ‘us’ vs. ‘them’ mentality in which the gain of one generation is the loss of another.

These are arguments for seeing ageing as a case of zero-sum, win-lose, politics. Policies can create win-lose intergenerational politics. The simplest example is pension system changes that leave younger people paying for a system they will not enjoy, while also having to make provisions for their own retirement. Political arguments can try to create and play on a public sense that generational politics is win-lose: the core of the ‘greedy geezers’ argument is precisely that people in one generation are taking too much from others. There is little natural generational tension in health politics, as we argue but political elites and policy can induce it.

1.3 Are Policy Concerns about Population Ageing Evidence-Based?

An important outstanding question is whether the policy worries about population ageing are backed up by evidence. To shed light on this, the European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies initiated a study series on the Economics of Healthy and Active Ageing. The series investigates key policy questions associated with population ageing, bringing together findings from research and country experiences. This includes reviews of what is known about the health and long-term care costs of older people, as well as many of the economic and societal benefits of healthy ageing. The series also explores policy options within the health and long-term care sectors, as well as other areas beyond the care sector, which either minimize avoidable health and long-term care costs, support older people so that they can continue to contribute meaningfully to society or otherwise contribute to the sustainability of care systems in the context of changing demographics. The evidence is quite clear that population ageing will not become a major driver of health spending trends, and that even though there will be labour market changes associated with population ageing, older people remain productive (whether they are paid or unpaid), at least to a greater extent than the data often used would suggest.

1.3.1 Population Ageing Will Not Become a Major Driver of Health Expenditure Growth

Generally, developed countries find that per person health expenditures are higher amongst older people. The superficially reasonable inference is often that increased population ageing will lead to a steep increase in health spending. One recent study (Reference Williams, Lawrence and DavisG.Williams et al., 2019) applied data on public health expenditure patterns by age to population projections for the European Union and found only an insignificant effect between health spending growth and population up until 2060. The result would add less than 1 percentage point per year to per person annual growth. The study also considered an extreme scenario wherein per person health expenditures for older people compared with their younger counterparts are significantly higher than current EU health expenditure data suggest. Even in such a scenario, population ageing only increases the overall EU health spending share of GDP by 0.85 more percentage points in 2060 compared to the baseline projection.

A review of literature (Cylus et al., 2018) found that health care costs do increase for older people right before they die, usually due to increased hospitalizations, but that this is less so the case with the ‘older old’ (80+). Overall, in many countries, after a certain age, the older people are when they die, the less the cost. This is perhaps due to the fact that, after a certain age, fewer resource-intensive interventions are used. This suggests that increased longevity could potentially result in an even smaller contribution to health spending growth due to population ageing than would currently be predicted.

Likewise, caring for older adults or the ‘older old’ is not as costly to finance as some may think, especially considering that they contribute economic and social value to society when they are healthy and active (Reference Evans, McGrail, Morgan, Barer and HertzmanEvans et al., 2001; Reference Jayawardana, Cylus and MossialosJayawardana et al., 2019). The first reason is that population ageing only gradually affects health expenditure forecasts, as opposed to cost drivers such as price growth and technological innovation, which have a substantially greater impact. Secondly, while demand for long-term care (both nursing homes and at home care) will undoubtedly increase, it will increase from a very low baseline. It was projected that the total expenditure needed for the long-term care of older adults is expected to increase by 162 per cent from 2015 to 2035 under the baseline scenario, but as a share of GDP this depicts an increase of only 1.02 per cent to 1.68 per cent (Reference Wittenberg, Hu and HancockWittenberg et al., 2018).

1.3.2 Population Ageing Will Lead to Changes in Paid and Unpaid Work, but These Can Be Managed

Cylus et al. (2018) also explained that the changes in paid and unpaid work as a result of population ageing are not necessarily unmanageable. Population ageing leads to an increase in the number of retirees, resulting in a decrease in the amount of people engaged in paid work. While this trend is unavoidable, there are four points that suggest it is unlikely to spell catastrophe for societies. The first is that some older adults choose to continue participating in the paid workforce well after they have retired, which is beneficial as they continue to contribute to a society’s economic output. The second point shows that while it is true that older people’s consumption is predominantly financed through public transfers, there are many older adults that pay for (part of) their consumption through private sources (either through a continued income from work or through accumulated assets). Health is a key predictor of asset accumulation; people in poor health are unable to accumulate substantial assets throughout their life-course as they have shorter life expectancies, lower earnings and higher out-of-pocket health care costs, highlighting that keeping older adults in good health is exceptionally important. Third, even if older adults are not in paid employment, they still pay consumption and non-labour-related taxes, thereby contributing to public-sector revenues. Finally, there are many unpaid workers, particularly older adults, who still produce outputs that generate economic and social value. A generally invisible non-market-based output is that of an informal caregiver. These caregivers can be young adults caring for an older family member or older adults caring for either grandchildren or the ‘older old’. The societal value of such unpaid work is substantial but not regularly quantified, and therefore generally goes unrecognized.

1.4 The Coronavirus Pandemic: Intergenerational Conflict or Revealing Consequences of Longstanding Inequalities?

The 2020 coronavirus global pandemic is a very recent and clear example of the political choices that could pit generations against each other. As the pandemic swept the world, governments had to walk a narrow path (Reference Greer, King, da Fonseca and Peralta-SantosGreer et al., 2020; Reference Rajan, Cylus and McKeeRajan et al., 2020): manage the pandemic using public health measures such as business restrictions to slow spread, while cushioning the economic blow with expansive social policy. This bought time for governments to build systems to test, trace, isolate, and support people, to attain something like normal society by the end of 2020. Most governments did not manage to stay on this narrow path, and instead fell into making tradeoffs between the economy and public health (Reference Greer, King, Peralta-Santos and Massard da FonsecaGreer et al., 2021). The inequalities in COVID-19 mortality in rich countries often meant political debates about how to value the lives of older people against the putative economic benefits of early reopening.

The stakes are made much higher by the needless and tragic tradeoffs between people in the COVID-19 pandemic. As a US newspaper columnist wrote, it mattered greatly whether we highlighted the age effects of the pandemic, calling it a ‘boomer remover’, or the race, class and gender inequalities it revealed, which in the case of the USA made it a ‘brother killer’ afflicting Black men (Reference BlowBlow, 2020). The same exercise could be done for any country. The virus targets people unequally. The odds of catching it vary with employment and reflect inequalities: once the virus is circulating in a population, the people most at risk of catching it are those who are in constant contact with others, in confined spaces, for long periods of time. That explains why abattoirs, prisons and nursing homes were all hot spots in many places. The key inequalities there are not about age; they are about who works in ‘essential’ tasks, such as caring work, that are often poorly paid and largely carried out by women, people of colour and immigrants. They are also about crowded and multigenerational living arrangements where it is hard to block spread within a household. Crowding and multigenerational family living arrangements are not evenly distributed in the population. Even among nursing homes in the USA, ones with more Black and Latino patients had higher infection and mortality rates (Reference CurtisCurtis, 2020). The risk of hospitalization and death from the virus, then, varied with age and other co-morbidities such as hypertension and diabetes. Again, these reflect other inequalities such as class, race and ethnicity. COVID-19 is clearly more dangerous to older people, but the odds of catching it and having the other co-morbidities that make it more dangerous are all reflective of deeper social inequalities from which age is mostly a distraction. COVID-19 belies simple narratives of win-lose intergenerational politics and policies. Not only did the deaths in homes for older people remind us of how poorly treated many of them are, it also showed that for all the intergenerational enmity pundits discuss, younger people were willing to stay home for them.

1.5 Win-Win Policy and Politics: the Life-Course Approach

What is the alternative to a zero-sum politics of ageing? We argue for win-win policies. Win-win policies aim for a positive-sum collective outcome, and the analytical tool that is most useful in identifying positive-sum collective outcomes in health and ageing issues is the life-course approach. Ageing is a process that takes place over a lifetime, beginning before birth and ending upon death. Nor is it a static process specific to a certain age group. Rather, it is a continuous development throughout one’s lifetime (Reference Kalache and KickbuschKalache & Kickbusch, 1997). In order to better see the case of ageing as such, a life-course concept was developed. This is a holistic examination of the various life stages, beginning with embryonic and foetal life, infancy, early childhood, school age, adolescence and reproductive age (including pre-conception), all the way up to old age (Reference Aagaard-Hansen, Norris, Maindal, Hanson and FallAagaard-Hansen et al., 2019). Life-course approaches are sometimes misunderstood to simply mean that we should focus on the very young, but understood correctly a life-course perspective identifies positive interventions at every age. The life-course perspective not only shows that a person’s current health is shaped by early exposures to physical, environmental and psychological factors (Reference Jones, Gilman and ChengJones et al., 2019), but also helps in understanding the origin, persistence and transmission of health disparities across generations (Reference BravemanBraveman, 2009; Reference Kuh, Ben-Shlomo, Lynch, Hallqvist and PowerKuh et al., 2003).

In order to be able to address transgenerational disparities and the disadvantages they bring with them, interventions need to envelop multi-generations, which implies looking towards all-encompassing solutions such as universal primary prevention, strengthening families and building children’s skills through adolescence and young adulthood (Reference Jones, Gilman and ChengJones et al., 2019). With every child able to reach his or her potential to be a healthy, engaged, productive citizen, the skills to plan for and parent the next generation are secured (Reference Cheng, Johnson and GoodmanCheng et al., 2016). In this way, a life-course perspective is incorporated into health disparities interventions by seeing the whole person, the entire family and the comprehensive community system (Reference Cheng and SolomonCheng & Solomon, 2014).

If the goal is healthy ageing, then policies and initiatives must encourage the healthy development of the individual so that human capital can be accumulated and maintained over the course of one’s life (Reference BovenbergBovenberg, 2007). The ultimate goal of the life-course perspective is to help individuals maintain the highest possible level of functional capacity throughout all stages of their life while reducing inequalities not only between gender and classes, but also between the generations (Reference Anxo, Bosch, Rubery, Anxo, Bosch and RuberyAnxo et al., 2010).

The World Health Organization presents an action framework for policymakers that helps visualize the investments necessary within the various stages (WHO, 2007) while at the same time recognizing the connections across all stages and domains in life (Reference MaederMaeder, 2015). According to the Minsk Declaration assembled at the WHO European ministerial conference in Belarus in 2015 (WHO, 2015), an adaptation of a life-course approach in the context of health means the following:

recognizing that all stages of a person’s life are intricately intertwined with each other, with the lives of other people in society and with past and future generations of their families;

understanding that health and wellbeing depend on interactions between risk and protective factors throughout people’s lives;

taking action … early to ensure the best start in life; appropriately to protect and promote health during life’s transition periods; and together, as a whole society, to create healthy environments, improve conditions of daily life and strengthen people-centred health systems.

Successful applications of the life-course approach can be found in the initiatives brought forth by Iceland surrounding the economic crisis and its impact on welfare, as well as by Malta and its confrontation of obesity and its direct costs to the health care system.

Box 1.1 Icelandic Welfare Watch

Icelandic Welfare Watch

Problem: The initiative was established as a response to the Icelandic financial crisis in 2008 where the three largest banks collapsed, the national currency fell by 86 per cent, unemployment rose from 2 to 8 per cent and inflation increased from 6 to 18 per cent. This crisis caused major stress on public budgets whereby public authorities were made to operate under highly constrained conditions.

Initiative Aim: The objective was to create a system that could reduce the impact of health-related problems when a society was hit by economic collapse. This strategy included limiting the negative impact of the crisis on populations’ wellbeing, developing emergency responses and services for different social groups in situations of crisis and creating flexible employment solutions.

Life-Course Approach: Working groups were established to help children and families with children to ensure sufficient access to relevant services such as guaranteed school lunches. Additional working groups were developed to create social indicators responsible for tracking welfare across social groups over time with the goal of monitoring and informing policies and services. Furthermore, a steering group made up of local authorities, health service workers, ministers, etc., was created to implement measures to support households, draft guidelines for local authorities on budget reduction and define basic welfare and educational services.

Box 1.2 Healthy Weight for Life strategy

Healthy Weight for Life strategy (HWL) developed by Malta

Problem: The initiative was established in response to the immense problem of obesity in Malta, where 40–48 per cent of children and 58 per cent of adults are overweight and obese. This produces an excess direct cost for the Maltese health service estimated at €20 million per year, and amounted to 5.7 per cent of the country’s total health expenditure in 2008.

Initiative Aim: The overall aim of the HWL strategy is to curb and reverse the growing proportion of overweight and obese children and adults in the population in order to reduce the health, social and economic consequences of excess bodyweight.

Life-Course Approach: Promoting healthy eating in early years through the increased encouragement of breastfeeding and during a child’s school years through the use of school-wide competitions and guidelines for parents, but also at the workplace and in homes for the elderly. Incentives to encourage a higher intake of fruits and vegetables were implemented in 2011 and incentives for employers were established to foster healthy eating at the workplace. The introduction of hospital-wide regulations to ensure that canteens in hospitals and homes for elderly adults are following healthy dietary guidelines.

1.6 The Book in Brief

Many will argue that the reason societies don’t opt for win-win solutions is the selfish interests of older people; in other words, that we get win-lose policies because of win-lose politics, and it’s older people who sustain those politics. The argument runs that their numerical weight and political engagement mean that politicians attend to their interests, and that their interests are in generous benefits for themselves, paid for in ways that damage the interests of younger people. We argue in Chapter 3 that this argument is simply wrong in most countries. Even in the United States and United Kingdom, where it is probably most valid, it is not a very useful explanation of politics and policy. Older people are far more diverse than such an image suggests, and they do not vote as a bloc. In fact, many are generous to younger people, in their personal actions and in their politics. As common sense and our lived experience would suggest, many older people are very concerned for the welfare of their families and their societies. Thus, for example, it is perfectly coherent for older people to have voted on issues such as Brexit; a vote for either Leave or Remain could be intended as a vote to leave a better country for future generations. To say that older people should vote differently or not vote is to devalue their experience and assume their absolute egoism: a manifest error. Older people do not vote as a bloc because, as individuals, their lives are shaped by many other factors that are more important than age: class, gender, ethnicity, nationality, rurality, family status and all the other factors that cumulate into an individual voter’s approach to the world.

Even if an older persons’ bloc vote did exist, there is actually no reason to expect that politicians would listen to it. This might come as a surprise to those who expect politicians to chase the median voter (aka the centre of the electorate) but is borne out by a great deal of political science research. Chapter 4 shows that there is very little political science research suggesting that policies of any kind are driven by electoral demand. Rather, policy is shaped by factors primarily of interest to elites (e.g. a perception of fiscal unsustainability, or EU law or international advice), interest group activities (e.g. the lobbying of unions, employers and others) and internal arguments among senior politicians about what strategies to pursue in order to win elections. Collectively, these elite interests and coalitions shape the policies and agendas offered to voters (Reference Greer, Lodge, Page and BallaGreer, 2015; Reference KingdonKingdon, 2010). The preferences of the putative median voters can change with framing and agenda-setting, which is why median voter models are essentially misleading. This is a point with vast supporting evidence in political science, but one that runs contrary to comfortable ideas about politicians ‘pandering’ (Reference Jacobs and ShapiroJacobs & Shapiro, 2000), and also runs contrary to comfortable ideas that modern democratic political systems make decisions that reflect exogenous voters’ views rather than complex interest politics in which public opinions and elections are only one, malleable, component (Reference Hacker and PiersonHacker & Pierson, 2014). We should not focus the blame on voters of any age if they are primarily responding to agendas set by others.

If elite supply of policy ideas rather than voters’ demand for electoral ideas shapes the agenda and the decisions, then the road to understanding decisions about ageing and health starts with understanding the supply of ideas. Chapter 5 focuses on the politics of the supply of ideas. Policies can powerfully shape the way that individual people, geographic places and larger polities experience demographic changes and the ensuing politics. It shows that there are multiple, complex, ways in which coalitions can come together to produce win-win solutions. Women’s organizations, public sector unions and providers of health and long-term care all appear as advocates for life-course approaches to ageing. This reflects their interests: for example, organizations representing the largely female and often precarious long-term care workforce might have an interest in expanded access and funding for care services, while working women might appreciate assistance with their caring responsibilities. Universal long-term care, for example, might be championed by a coalition of employers, unions and women’s organizations who want to keep working-age female employees in the labour force instead of having them drop out to focus on caring, providers and unions of their employees who seek a stable source of funding for their businesses, local governments eager to dispose of expensive responsibilities to care for indigent older people, and a finance ministry concerned about the loss of working age women to the unpaid care sector. An option thus formulated could then be put to voters in the expectation that many people, such as working women, would like it. Indeed, this is almost exactly what happened in Japan (Reference SchoppaSchoppa, 2006).

These two chapters, together, make a key claim of this book: age, however understood, is a weak predictor of anything to do with the politics of ageing. Once rigorous controls for variables such as education, income and wealth have been introduced, age itself is a weak predictor of people’s opinions, and public opinion is a weak predictor of politics. Instead of drawing facile lines from demographics through interests and public opinion to policies, it makes more sense to reverse the direction of causality and understand policy decisions and agendas as the product of arguments among and within coalitions of elites and interests. Organized groups such as political parties, employers, unions, the finance sector (insurers), women’s organizations and organizations that represent older people shape policy ideas, political strategies and the definition of problems (Reference Greer, Lodge, Page and BallaGreer, 2015).

Framing the politics of ageing as a war of the generations obscures what really shapes the lives and views of older as well as younger people. Chapter 6 reframes the stakes of ageing politics, arguing that the real question of ageing in politics and health should be: who gets to be old? The ‘Greedy Geezer’ narrative of self-serving older people implicitly focuses our attention on wealthy older people, summoning an image of people who retire early to spend decades on cruise ships, and obscuring the experiences and problems of those who are not so lucky. What truth it has comes from the simple fact that many of the least lucky, the people who are most affected by health and broader socioeconomic inequalities, don’t get to be old. Systemic inequities in societies are reflected in health data, which includes both life expectancy and healthy life expectancy. There are many policies that have some ability to reduce health inequalities, typically through reducing broader inequalities.

As sports commentators say, it is important to keep one’s eye on the ball. Consider a basic thought experiment in the social policy of ageing. If we argue that universal public long-term care is unaffordable, all we propose to do is change the ways in which long-term care is provided for most people. If we finance long-term care out-of-pocket, we can expect the predictable effects of any shift of social expenditure to out-of-pocket payments. The very wealthy might not see much change. Middle-class families with some patrimony will see the costs of care eat into their inheritances. Working-class families will probably see a reduction in their disposable income, whether they spend it on care provision or have a family member reduce their participation in paid employment in order to provide informal care. For the unluckiest, old age will mean whatever system exists in a given country to look after the indigent. As COVID19 hotspots in nursing homes show, that system is usually not set up to maximize older people’s wellbeing. On the other hand, if we establish a public universal system, it will concentrate a very large expenditure into one programme, and while that programme might be attractive, it will also contain intimidating upfront costs. Those groups in society, especially high-earning individuals who do not expect to benefit but do expect to pay for it in their taxes, will be opponents, even if it is in principle an efficient way to maximize overall social welfare by ensuring that everybody has a guarantee of decent long-term care, financed by the broadest possible pool. As this stylized example might make clear, the distributional decisions are not intergenerational. They are intra-generational, deciding how resources will be allocated between classes.

Chapter 7 keeps our eye on the ball, evaluating the inequality dynamics of two different events: German Reunification and the rise of English investment in reducing inequalities under Labour governments (1996–2010) followed by its fall under Conservative-led governments since 2010. These two very different events both produced discontinuities which allowed us to understand the impact of win-win (positive sum) or win-lose (zero-sum) policies on who even gets to be old, let alone live well. Inequalities can be reduced, but the effective way to reduce them is by focusing not on putative intergenerational inequalities but rather on more deeply rooted inequalities that reproduce across generations and are made up of more than the legacies of the political economies that people occupied when they were younger.

The conclusion points back to the extent to which the talk of an ‘ageing crisis’ that so preoccupies many policy analysts despite its scant empirical foundations has shaped the supply side of policies. Zombie ideas such as ‘ageing societies face increased health care costs’ continue to march along despite multiple efforts to kill them off. In the face of those zombie ideas, this chapter argues that real-life studies show how policies that use life-course approaches to achieve equity make real differences, and the kind of austerity favoured by many advocates of intergenerational accounting actively harms society.

1.7 Conclusion

Much of the global discourse about ageing and health is needlessly gloomy. One of the great postwar achievements, the welfare state, has enabled another wondrous outcome: a human society in which most people live for a long time. But for some, these two goals are now in conflict, and the ageing society makes the welfare state that helped birth it unsustainable. Some view many of the aforementioned threats as unavoidable and unsolvable and conclude that the only remedy is to tear down the welfare state, dismantle entitlement programmes and raise retirement ages. What should be viewed as one of social policy’s greatest achievements is instead the impetus for its destruction.

Ageing as a health policy problem is very manageable, and there is lots of good research and policy thinking on topics such as the best way to recalibrate primary care services to respond to ageing populations. As shown above, there is also little reason to expect that ageing societies will have substantially higher health care costs, or even that we are measuring everything that matters, given the role of older people in informal care, civil society and other unpaid roles that often conflict with paid employment but are crucial to people, families and societies.

It might be surprising to learn that ageing is not necessarily a big problem for the fiscal sustainability of health systems; it might also be surprising to learn that the politics of ageing are not necessarily the politics of intergenerational warfare. Not only are win-win solutions possible, that are beneficial all along the life-course, but the politics of those solutions are more concrete and personal than airy talk of generations suggests. On one side, voters have concrete and personal experiences and interests, born of experiences as disparate as dropping out of paid employment to care for parents and depending on parents’ caring in order to work. Those experiences do not translate in any simple way into a demand for greater or lesser taxes or social expenditures. People can be generous as well as selfish, and even if they are selfish, they will often define their selfishness in terms of their family, locale, race, ethnicity or class rather than age. Elites, meanwhile, are paid to represent groups, shape agendas and make policy, and have much more specific interests, whether they represent doctors, care homes, the elderly, workers, women, the finance ministry or any of the many other groups seeking advantage in the politics of ageing societies. Those elites’ interactions, and the coalitions and conflicts among them, shape what policies are offered to voters and what drive politics.

This book brings together research on why population ageing is often (erroneously) viewed cataclysmically, particularly from a health financing perspective, and reviews approaches to get the win-win ageing policies we need. The ‘crisis’ that Western Europe is facing is not so much that demographics are shifting as that there are currently few sufficient and effective policies in place to support the shift in a sustainable way. Ageing societies are not doomed to crisis, or even to difficulties sustaining their welfare state. There are win-win solutions, which can be inferred from a life-course approach, but they often require overcoming narrow interests by building broader coalitions.

The controversy that this book speaks to is the general belief that wealthy older people, assumed to be a homogeneous voting group, vote for policies that benefit themselves; this is a falsity depicted both demographically and theoretically. Older people do not vote homogeneously and in most polities policy is only partially a product of electoral demands. In addition, as shown briefly in this chapter, it is incorrect to think that all older people are poor, but at the same time not all of them are rich; this is a very heterogeneous group, which also makes them very susceptible to inequalities. Given the heterogeneity among older people there are some that may need support; this support is not that expensive and can be made intergenerationally fair through the implementation of not ageing policies but life-course policies.

Coalitions are the result of intersecting solidarities: intergenerational and class as well as citizenship and gender. Coalitions are the answer to establishing healthy ageing policies without sacrificing people of any age. Policymakers need to understand how gender, class and region collectively shape ageing politics in order to be able to understand the tradeoffs in place. Only with this understanding can equitable and effective win-win policies be made.

The argument that the book makes is a simple one: Western societies can evolve from the politics of unhealthy ageing produced by lose-lose policies to the politics of healthy ageing by following a life-course approach through the adaptation of win-win policies. The aim is to solve the “ageing crisis” in the same it way it was created: politics. We argue that using political imagination can point us to policies which decrease both inter- and intragenerational inequalities.