160 results

12 - Style

- from Part II - Forms of the Poem

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Companion to the Poem

- Published online:

- 30 May 2024

- Print publication:

- 06 June 2024, pp 196-210

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

3 - The Tricks of the Writing Trade

-

- Book:

- Compelling Communication

- Published online:

- 30 May 2024

- Print publication:

- 30 May 2024, pp 67-92

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

18 - Finding Your Voice

- from Part IV - Building a Career

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Companion to Composition

- Published online:

- 25 May 2024

- Print publication:

- 30 May 2024, pp 291-300

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Part III - Styles, Conventions, and Issues

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Companion to Composition

- Published online:

- 25 May 2024

- Print publication:

- 30 May 2024, pp 175-284

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 15 - Style and Language

- from Part III - Literary Background

-

-

- Book:

- Jonathan Swift in Context

- Published online:

- 02 May 2024

- Print publication:

- 09 May 2024, pp 116-122

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

8 - Ecce Mann

-

-

- Book:

- Nietzsche and Literary Studies

- Published online:

- 03 May 2024

- Print publication:

- 25 April 2024, pp 186-209

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

1 - Heraclitus’ Clarity

-

-

- Book:

- Nietzsche and Literary Studies

- Published online:

- 03 May 2024

- Print publication:

- 25 April 2024, pp 16-36

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

24 - Variation in Gesture: A Sociocultural Linguistic Perspective

- from Part V - Gestures in Relation to Interaction

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Handbook of Gesture Studies

- Published online:

- 01 May 2024

- Print publication:

- 18 April 2024, pp 616-640

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

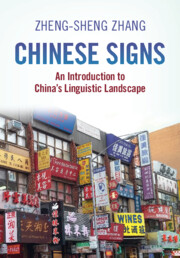

1 - Why Signs?

- from Part I - General Characteristics

-

- Book:

- Chinese Signs

- Published online:

- 29 February 2024

- Print publication:

- 07 March 2024, pp 3-9

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Possessive pronouns in Welsh: Stylistic variation and the acquisition of sociolinguistic competence – Corrigendum

-

- Journal:

- Language Variation and Change / Volume 36 / Issue 1 / March 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 06 March 2024, p. 121

- Print publication:

- March 2024

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Chinese Signs

- An Introduction to China's Linguistic Landscape

-

- Published online:

- 29 February 2024

- Print publication:

- 07 March 2024

Possessive pronouns in Welsh: Stylistic variation and the acquisition of sociolinguistic competence

-

- Journal:

- Language Variation and Change / Volume 36 / Issue 1 / March 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 30 January 2024, pp. 25-48

- Print publication:

- March 2024

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Chapter 21 - Messiaen and the Organ Recordings

- from Part III - Composers, Performers, and Critics

-

-

- Book:

- Messiaen in Context

- Published online:

- 09 November 2023

- Print publication:

- 30 November 2023, pp 190-198

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 4 - Messiaen and the Paris Conservatoire

- from Part I - Mondial Messiaen

-

-

- Book:

- Messiaen in Context

- Published online:

- 09 November 2023

- Print publication:

- 30 November 2023, pp 27-36

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

4 - How to Watch Jazz

- from Part I - Elements of Sound and Style

-

-

- Book:

- Jazz and American Culture

- Published online:

- 09 November 2023

- Print publication:

- 30 November 2023, pp 64-78

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 12 - Walter Pater, Charles Lamb, and ‘the value of reserve’

- from Part II - Individual Authors: Early Moderns, Romantics, Contemporaries

-

-

- Book:

- Walter Pater and the Beginnings of English Studies

- Published online:

- 14 November 2023

- Print publication:

- 09 November 2023, pp 239-254

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 7 - Walter Pater, Second-Hand Stylist

- from Part I - General

-

-

- Book:

- Walter Pater and the Beginnings of English Studies

- Published online:

- 14 November 2023

- Print publication:

- 09 November 2023, pp 133-148

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Introduction: Pater and English Literature

-

-

- Book:

- Walter Pater and the Beginnings of English Studies

- Published online:

- 14 November 2023

- Print publication:

- 09 November 2023, pp 1-32

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 6 - Form, Matter, and Metaphysics in Walter Pater’s Essay on ‘Style’

- from Part I - General

-

-

- Book:

- Walter Pater and the Beginnings of English Studies

- Published online:

- 14 November 2023

- Print publication:

- 09 November 2023, pp 118-132

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

7 - How Does Grammar Combine with Other Elements of Language?

-

- Book:

- Socio-syntax

- Published online:

- 19 October 2023

- Print publication:

- 02 November 2023, pp 171-206

-

- Chapter

- Export citation