66 results

Religion as Liberal Politics

-

- Journal:

- Journal of Law and Religion , First View

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 29 April 2024, pp. 1-22

-

- Article

- Export citation

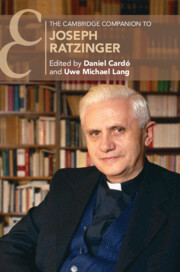

The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Ratzinger

-

- Published online:

- 25 January 2024

- Print publication:

- 21 December 2023

1 - Essays to Do Good: Puritanism and the Birth of the American Essay

- from Part I - The Emergence of the American Essay (1710–1865)

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge History of the American Essay

- Published online:

- 28 March 2024

- Print publication:

- 14 December 2023, pp 15-31

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

5 - The Essay and Transcendentalism

- from Part I - The Emergence of the American Essay (1710–1865)

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge History of the American Essay

- Published online:

- 28 March 2024

- Print publication:

- 14 December 2023, pp 81-95

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

12 - Revolution at Geneva: Genevans in Revolution

- from Part II - Western, Central, and Eastern Europe

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge History of the Age of Atlantic Revolutions

- Published online:

- 18 October 2023

- Print publication:

- 09 November 2023, pp 329-348

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

7 - ‘Popes and Caesars’

- from Part III - Materiality and Spectacle

-

-

- Book:

- Victorian Engagements with the Bible and Antiquity

- Published online:

- 28 September 2023

- Print publication:

- 12 October 2023, pp 184-208

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 4 - “Gathered again from the ash”

- from Part II - The Politics of Memory and Affect

-

-

- Book:

- Memory and Affect in Shakespeare's England

- Published online:

- 07 June 2023

- Print publication:

- 27 July 2023, pp 89-105

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Religious Dynamics and Conflicts in Contemporary Ethiopia: Expansion, Protection, and Reclaiming Space

-

- Journal:

- African Studies Review / Volume 66 / Issue 3 / September 2023

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 11 April 2023, pp. 721-744

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

9 - Preachers, Puritans and the Religion of Lawyers

-

- Book:

- The Inns of Court under Elizabeth I and the Early Stuarts

- Published online:

- 15 January 2023

- Print publication:

- 05 January 2023, pp 235-271

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

1 - Introduction: Life, Work and Historical Context

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Companion to Pufendorf

- Published online:

- 25 November 2022

- Print publication:

- 17 November 2022, pp 1-32

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Beyond the Underdog Mentality: Philo-Semitism amongst Protestant Rescuers in Wartime Ukraine

-

- Journal:

- Harvard Theological Review / Volume 115 / Issue 4 / October 2022

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 09 November 2022, pp. 538-565

- Print publication:

- October 2022

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

15 - Protestantism and Human Dignity in South Korea

-

-

- Book:

- Human Dignity in Asia

- Published online:

- 26 July 2022

- Print publication:

- 15 September 2022, pp 356-378

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

A New Jerusalem: Flavius Josephus in Early America

-

- Journal:

- Church History / Volume 91 / Issue 3 / September 2022

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 16 December 2022, pp. 555-574

- Print publication:

- September 2022

-

- Article

- Export citation

3 - Long-Run Factors

-

-

- Book:

- Why Democracies Develop and Decline

- Published online:

- 28 June 2022

- Print publication:

- 23 June 2022, pp 55-79

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Conclusion

-

- Book:

- Reformation in the Low Countries, 1500-1620

- Published online:

- 02 June 2022

- Print publication:

- 09 June 2022, pp 182-196

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Law at the Backbone: The Christian Legal Ecumenism of Norman Doe

-

- Journal:

- Ecclesiastical Law Journal / Volume 24 / Issue 2 / May 2022

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 29 April 2022, pp. 192-208

- Print publication:

- May 2022

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Chapter 38 - Faith, Spirituality, and the Church

- from Part V - British Sociocultural, Religious, and Political Life

-

-

- Book:

- Benjamin Britten in Context

- Published online:

- 31 March 2022

- Print publication:

- 21 April 2022, pp 334-342

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

II.3 - Theological Method and the Foundations of Protestant Faith

- from Part II - Pierre Bayle and the Emancipation of Religion from Philosophy

-

- Book:

- The Kingdom of Darkness

- Published online:

- 23 March 2022

- Print publication:

- 31 March 2022, pp 375-422

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Four Axes of Mission: Conversion and the Purposes of Mission in Protestant History

-

- Journal:

- Transactions of the Royal Historical Society / Volume 32 / December 2022

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 22 March 2022, pp. 113-133

- Print publication:

- December 2022

-

- Article

- Export citation

Chapter 3 - Christianity

- from Part I - Historical Developments

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Companion to British Romanticism and Religion

- Published online:

- 01 October 2021

- Print publication:

- 21 October 2021, pp 31-49

-

- Chapter

- Export citation