369 results

12 - Sexuality in Post-war Liberal Democracies

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge World History of Sexualities

- Published online:

- 26 April 2024

- Print publication:

- 16 May 2024, pp 247-274

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

2 - A History of Misinformation

- from Part I - Setting the Stage

-

- Book:

- The Psychology of Misinformation

- Published online:

- 28 March 2024

- Print publication:

- 04 April 2024, pp 22-34

-

- Chapter

-

- You have access

- HTML

- Export citation

4 - The Control of Suicide Promotion over the Internet

-

- Book:

- Practical Ethics in Suicide

- Published online:

- 15 February 2024

- Print publication:

- 22 February 2024, pp 67-81

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

A Too Intimate Internet: What is Wrong with Precise Audience Selection?

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

4 - The Public Forum

-

- Book:

- We Hold These Truths

- Published online:

- 30 November 2023

- Print publication:

- 21 December 2023, pp 98-135

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

10 - Inferring Irony Online

- from Part IV - Irony in Linguistic Communication

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Handbook of Irony and Thought

- Published online:

- 20 December 2023

- Print publication:

- 07 December 2023, pp 160-180

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Constitutional Liberties and Cyberspace: Analysing the Anuradha Bhasin v Union of India Case and its Impact on Fundamental Rights

-

- Journal:

- Legal Information Management / Volume 23 / Issue 4 / December 2023

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 02 February 2024, pp. 276-281

- Print publication:

- December 2023

-

- Article

- Export citation

12 - Against Procedural Fetishism in the Automated State

- from Part III - Synergies and Safeguards

-

-

- Book:

- <i>Money, Power, and AI</i>

- Published online:

- 16 November 2023

- Print publication:

- 30 November 2023, pp 221-240

-

- Chapter

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

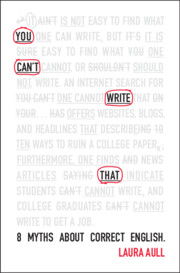

Chapter Eight - Myth 8 You Can’t Write That Because Internet

-

- Book:

- You Can't Write That

- Published online:

- 09 November 2023

- Print publication:

- 23 November 2023, pp 145-160

-

- Chapter

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Brief scales for the measurement of target variables and processes of change in cognitive behaviour therapy for major depression, panic disorder and social anxiety disorder

-

- Journal:

- Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy , First View

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 21 November 2023, pp. 1-18

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Chapter 8 - Conspiracy Thinking

- from Part IV - Examining Societal Discontent

-

- Book:

- The Fair Process Effect

- Published online:

- 26 October 2023

- Print publication:

- 09 November 2023, pp 89-102

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

You Can't Write That

- 8 Myths About Correct English

-

- Published online:

- 09 November 2023

- Print publication:

- 23 November 2023

-

- Book

-

- You have access

- Open access

- Export citation

Chapter 14 - Online Outreach and Support Provision: An Empirically Informed Approach and Case Illustration

- from Section 3 - Social Media as a Resource

-

-

- Book:

- Social Media and Mental Health

- Published online:

- 11 October 2023

- Print publication:

- 12 October 2023, pp 139-149

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 7 - Recruitment to QAnon

- from Part II - Recruiting and Maintaining Followers

-

-

- Book:

- The Social Science of QAnon

- Published online:

- 14 September 2023

- Print publication:

- 28 September 2023, pp 104-120

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

10 - Fascism in American Culture

- from Part IV - Countering Fascism in Culture and Policy

-

-

- Book:

- Fascism in America

- Published online:

- 14 September 2023

- Print publication:

- 14 September 2023, pp 313-351

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

A systematic survey of the online trade in elephant ivory in Singapore before and after a domestic trade ban

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

As a new challenger approaches, how will modern psychiatry cope with ’shifting realities’?

-

- Journal:

- Acta Neuropsychiatrica / Volume 35 / Issue 6 / December 2023

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 18 August 2023, pp. 377-379

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- HTML

- Export citation

3rd Palaeontological Virtual Congress: palaeontology in the virtual era

-

- Journal:

- Earth and Environmental Science Transactions of The Royal Society of Edinburgh / Volume 114 / Issue 1-2 / July 2023

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 14 September 2023, pp. 1-4

- Print publication:

- July 2023

-

- Article

- Export citation

19 - Japanese Mass Media

- from Part III - Social Practices and Cultures in Modern Japan

-

-

- Book:

- The New Cambridge History of Japan

- Published online:

- 19 May 2023

- Print publication:

- 08 June 2023, pp 645-670

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Dr. Google’s Advice on First Aid: Evaluation of the Search Engine’s Question-Answering System Responses to Queries Seeking Help in Health Emergencies

-

- Journal:

- Prehospital and Disaster Medicine / Volume 38 / Issue 3 / June 2023

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 11 May 2023, pp. 345-351

- Print publication:

- June 2023

-

- Article

- Export citation