28 results

“Fit for Purpose?” Assessing the Ecological Fit of the Social Institutions that Globally Govern Antimicrobial Resistance

-

- Journal:

- Perspectives on Politics , First View

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 09 January 2024, pp. 1-22

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

A Pandemic Instrument Can Start Turning Collective Problems into Collective Solutions by Governing the Common-Pool Resource of Antimicrobial Effectiveness

-

- Journal:

- Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics / Volume 50 / Issue S2 / Winter 2022

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 09 March 2023, pp. 17-25

- Print publication:

- Winter 2022

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Adopting a Global AMR Target within the Pandemic Instrument Will Act as a Catalyst for Action

-

- Journal:

- Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics / Volume 50 / Issue S2 / Winter 2022

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 09 March 2023, pp. 64-70

- Print publication:

- Winter 2022

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

A Pandemic Instrument can Optimize the Regime Complex for AMR by Striking a Balance between Centralization and Decentralization

-

- Journal:

- Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics / Volume 50 / Issue S2 / Winter 2022

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 09 March 2023, pp. 26-33

- Print publication:

- Winter 2022

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

2 - The Afterlife of the Medieval Christian Warrior

-

-

- Book:

- Journal of Medieval Military History

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 07 October 2022

- Print publication:

- 17 June 2022, pp 17-34

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

A Global Pandemic Treaty Must Address Antimicrobial Resistance

-

- Journal:

- Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics / Volume 49 / Issue 4 / Winter 2021

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 10 January 2022, pp. 688-691

- Print publication:

- Winter 2021

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

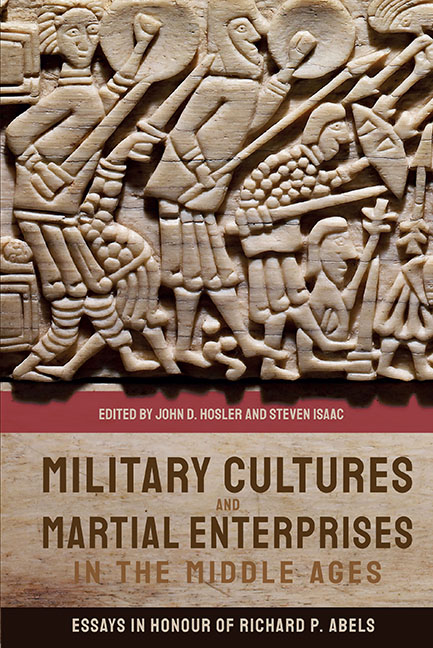

Frontmatter

-

- Book:

- Military Cultures and Martial Enterprises in the Middle Ages

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 21 October 2020

- Print publication:

- 19 June 2020, pp i-iv

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Notes on Contributors

-

- Book:

- Military Cultures and Martial Enterprises in the Middle Ages

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 21 October 2020

- Print publication:

- 19 June 2020, pp viii-x

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Introduction and Appreciation

-

-

- Book:

- Military Cultures and Martial Enterprises in the Middle Ages

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 21 October 2020

- Print publication:

- 19 June 2020, pp 1-13

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Tabula Gratulatoria

-

- Book:

- Military Cultures and Martial Enterprises in the Middle Ages

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 21 October 2020

- Print publication:

- 19 June 2020, pp 277-277

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

List of Illustrations

-

- Book:

- Military Cultures and Martial Enterprises in the Middle Ages

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 21 October 2020

- Print publication:

- 19 June 2020, pp vii-vii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Contents

-

- Book:

- Military Cultures and Martial Enterprises in the Middle Ages

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 21 October 2020

- Print publication:

- 19 June 2020, pp v-vi

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Military Cultures and Martial Enterprises in the Middle Ages

- Essays in Honour of Richard P. Abels

-

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 21 October 2020

- Print publication:

- 19 June 2020

Richard P. Abels’ Curriculum Vitae

-

- Book:

- Military Cultures and Martial Enterprises in the Middle Ages

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 21 October 2020

- Print publication:

- 19 June 2020, pp 257-261

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Index

-

- Book:

- Military Cultures and Martial Enterprises in the Middle Ages

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 21 October 2020

- Print publication:

- 19 June 2020, pp 262-276

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

HIGH DENSITY PIECEWISE SYNDETICITY OF PRODUCT SETS IN AMENABLE GROUPS

-

- Journal:

- The Journal of Symbolic Logic / Volume 81 / Issue 4 / December 2016

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 12 August 2016, pp. 1555-1562

- Print publication:

- December 2016

-

- Article

- Export citation

Adam Chapman. Welsh Soldiers in the Later Middle Ages, 1282–1422. Warfare in History. Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 2015. Pp. 282. $95.00 (cloth).

-

- Journal:

- Journal of British Studies / Volume 55 / Issue 3 / July 2016

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 10 June 2016, pp. 592-593

- Print publication:

- July 2016

-

- Article

- Export citation

On a Sumset Conjecture of Erdős

-

- Journal:

- Canadian Journal of Mathematics / Volume 67 / Issue 4 / 01 August 2015

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 20 November 2018, pp. 795-809

- Print publication:

- 01 August 2015

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Export citation

Contributors

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Dictionary of Philosophy

- Published online:

- 05 August 2015

- Print publication:

- 27 April 2015, pp ix-xxx

-

- Chapter

- Export citation