234 results

The Rapid ASKAP Continuum Survey III: Spectra and Polarisation In Cutouts of Extragalactic Sources (SPICE-RACS) first data release – CORRIGENDUM

-

- Journal:

- Publications of the Astronomical Society of Australia / Volume 41 / 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 03 June 2024, e039

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Evolutionary Map of the Universe (EMU): Observations of Filamentary Structures in the Abell S1136 Galaxy Cluster

-

- Journal:

- Publications of the Astronomical Society of Australia / Accepted manuscript

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 23 May 2024, pp. 1-18

-

- Article

- Export citation

219 Engagement as a Spectrum: Co-Developing and Implementing a Training Series to Enhance Researcher Capacity for Engaging Community and Patient Partners

- Part of

-

- Journal:

- Journal of Clinical and Translational Science / Volume 8 / Issue s1 / April 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 03 April 2024, p. 67

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- Export citation

38 Language and memory outcome after frontal or temporal resection for epilepsy

-

- Journal:

- Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society / Volume 29 / Issue s1 / November 2023

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 21 December 2023, pp. 912-913

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Export citation

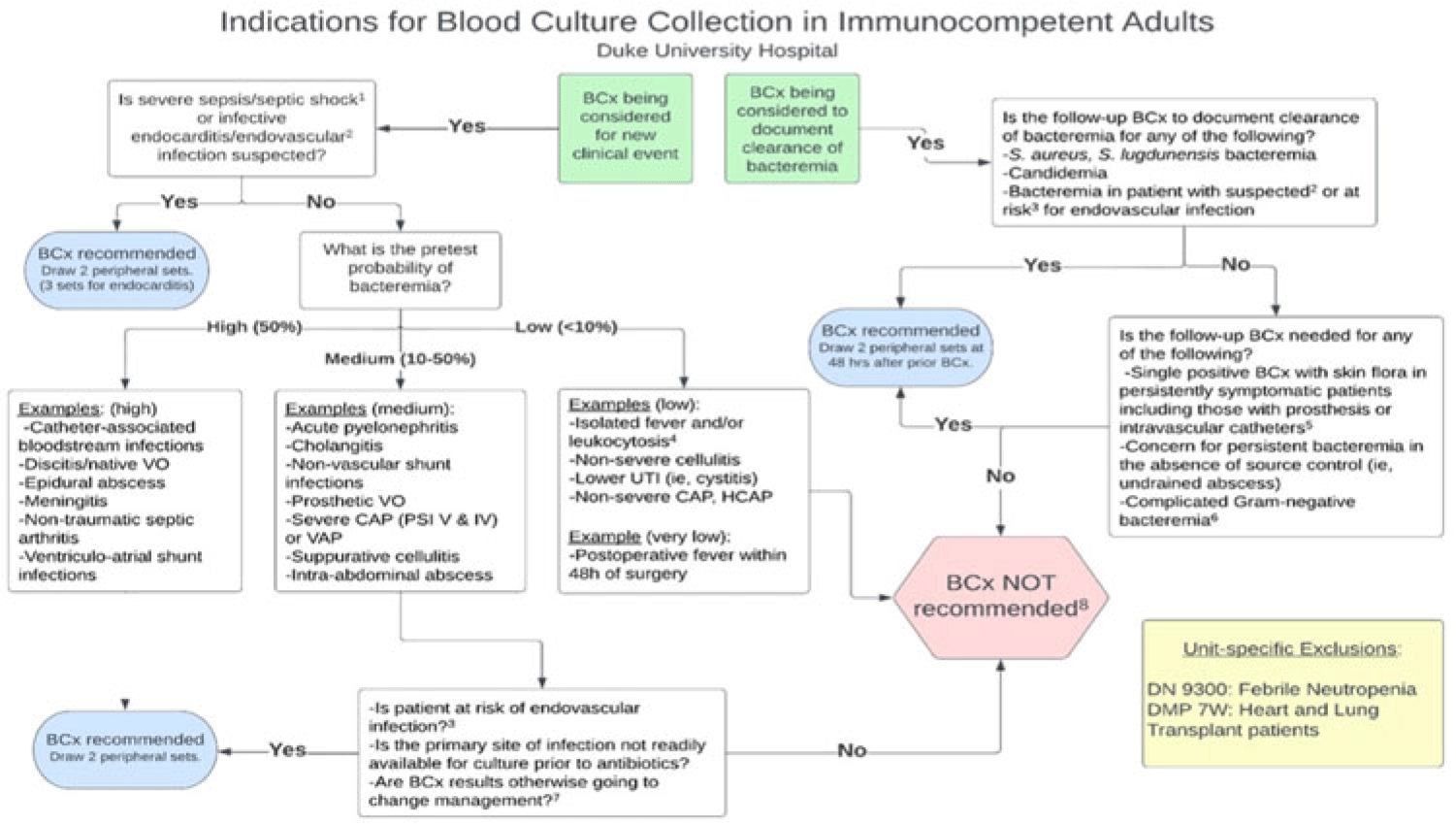

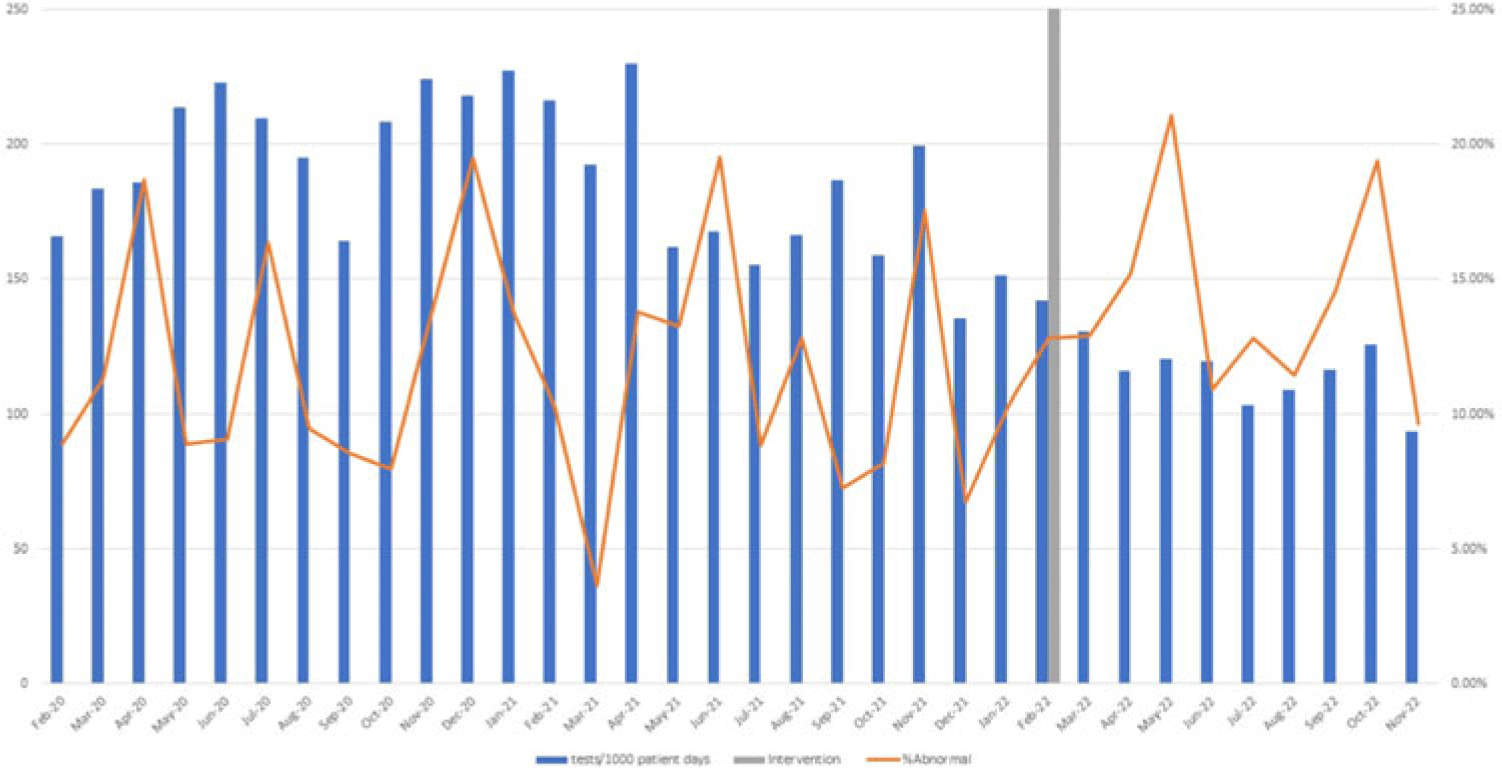

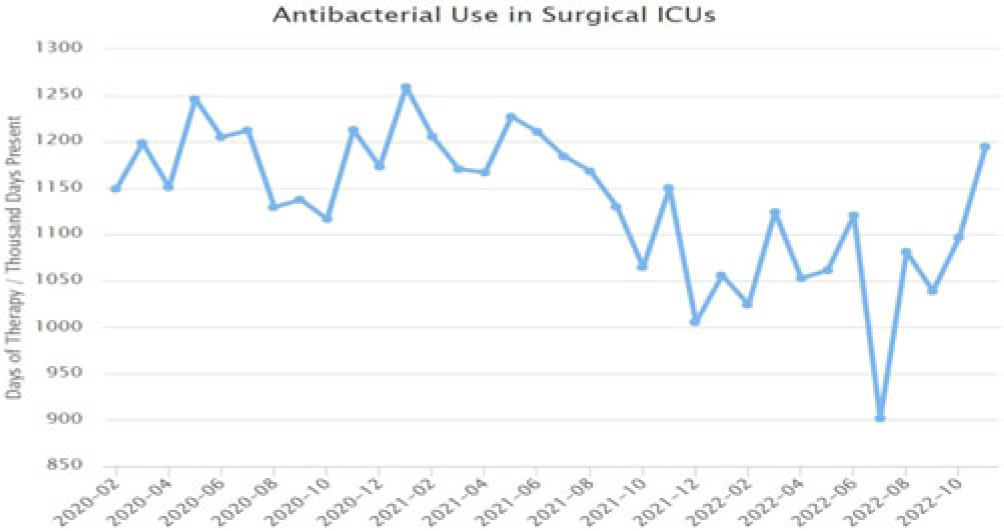

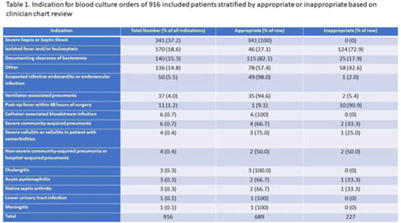

Implementation of a diagnostic stewardship intervention to improve blood-culture utilization in 2 surgical ICUs: Time for a blood-culture change

-

- Journal:

- Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology / Volume 45 / Issue 4 / April 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 11 December 2023, pp. 452-458

- Print publication:

- April 2024

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Racial disparities in Clostridioides difficile testing in three southeastern US hospitals

-

- Journal:

- Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology / Volume 45 / Issue 4 / April 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 20 November 2023, pp. 429-433

- Print publication:

- April 2024

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Strategies used for the COVID-OUT decentralized trial of outpatient treatment of SARS-CoV-2

-

- Journal:

- Journal of Clinical and Translational Science / Volume 7 / Issue 1 / 2023

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 07 November 2023, e242

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Lower redemption of monthly Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children benefits associated with higher risk of program discontinuation

-

- Journal:

- Public Health Nutrition / Volume 26 / Issue 12 / December 2023

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 09 October 2023, pp. 3041-3050

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Implementation of diagnostic stewardship in two surgical ICUs: Time for a blood-culture change

-

- Journal:

- Antimicrobial Stewardship & Healthcare Epidemiology / Volume 3 / Issue S2 / June 2023

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 29 September 2023, pp. s9-s10

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- Export citation

The Rapid ASKAP Continuum Survey III: Spectra and Polarisation In Cutouts of Extragalactic Sources (SPICE-RACS) first data release

-

- Journal:

- Publications of the Astronomical Society of Australia / Volume 40 / 2023

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 30 August 2023, e040

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Disinfection efficacy of Oxivir TB wipe residue on severe acute respiratory coronavirus virus 2 (SARS-CoV-2)

-

- Journal:

- Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology / Volume 44 / Issue 11 / November 2023

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 19 July 2023, pp. 1891-1893

- Print publication:

- November 2023

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

CONSTRUCTING A PRODUCT ARCHITECTURE STRATEGY AND EFFECTS (PASE) MATRIX FOR EVALUATION AND SELECTION OF PRODUCT ARCHITECTURES

-

- Journal:

- Proceedings of the Design Society / Volume 3 / July 2023

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 19 June 2023, pp. 1087-1096

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- Export citation

Comparative transmission of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron (B.1.1.529) and Delta (B.1.617.2) variants and the impact of vaccination: national cohort study, England

-

- Journal:

- Epidemiology & Infection / Volume 151 / 2023

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 20 March 2023, e58

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Optimizing reflex urine cultures: Using a population-specific approach to diagnostic stewardship

-

- Journal:

- Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology / Volume 44 / Issue 2 / February 2023

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 10 January 2023, pp. 206-209

- Print publication:

- February 2023

-

- Article

- Export citation

Belief bias and representation in assessing the Bayesian rationality of others

-

- Journal:

- Judgment and Decision Making / Volume 14 / Issue 1 / January 2019

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 01 January 2023, pp. 1-10

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

The Evolutionary Map of the Universe Pilot Survey – ADDENDUM

-

- Journal:

- Publications of the Astronomical Society of Australia / Volume 39 / 2022

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 02 November 2022, e055

-

- Article

- Export citation

Evaluation of hospital blood culture utilization rates to identify opportunities for diagnostic stewardship

-

- Journal:

- Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology / Volume 44 / Issue 2 / February 2023

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 08 August 2022, pp. 200-205

- Print publication:

- February 2023

-

- Article

- Export citation

Inequitable access: factors associated with incomplete referrals to paediatric cardiology

-

- Journal:

- Cardiology in the Young / Volume 34 / Issue 2 / February 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 18 July 2022, pp. 428-435

-

- Article

- Export citation

27 - Deceptive Cadence

-

- Book:

- Karl Straube (1873-1950)

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 26 May 2022

- Print publication:

- 15 April 2022, pp 368-383

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Part I - Berlin 1873–1897

-

- Book:

- Karl Straube (1873-1950)

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 26 May 2022

- Print publication:

- 15 April 2022, pp 5-6

-

- Chapter

- Export citation