Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Contributors

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- PART I THEORETICAL PERSPECTIVES

- 1 Rooted Cosmopolitanism: Emerging from a Rivalry of Distinctions

- 2 Assessing McDonaldization, Americanization and Globalization

- 3 Culture, Modernity and Immediacy

- PART II NATIONAL CASE STUDIES

- PART III TRANSNATIONAL PROCESSES

- PART IV EPILOGUE

- Rethinking Americanization

1 - Rooted Cosmopolitanism: Emerging from a Rivalry of Distinctions

from PART I - THEORETICAL PERSPECTIVES

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Contributors

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- PART I THEORETICAL PERSPECTIVES

- 1 Rooted Cosmopolitanism: Emerging from a Rivalry of Distinctions

- 2 Assessing McDonaldization, Americanization and Globalization

- 3 Culture, Modernity and Immediacy

- PART II NATIONAL CASE STUDIES

- PART III TRANSNATIONAL PROCESSES

- PART IV EPILOGUE

- Rethinking Americanization

Summary

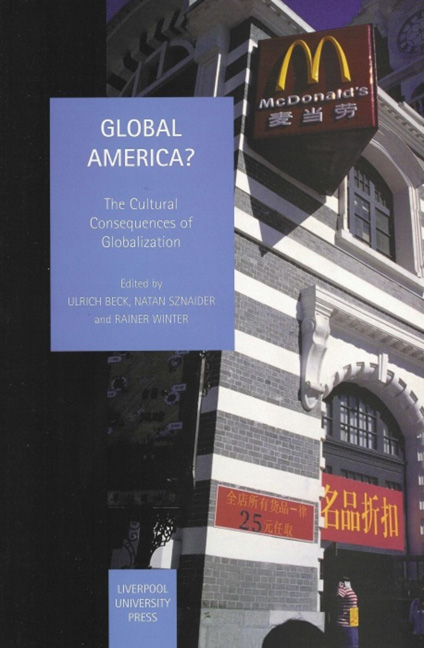

US presidents, including Bill Clinton and George W. Bush, tend to declare that the USA is the guiding light of the world. All draw on a long tradition, since Abraham Lincoln once described America as ‘the last best hope of the earth’. There are, however, many people, even in the USA, who would take the opposite stance. Whereas Clinton saw America as a vector for expansion of the free market and democracy throughout the world, others see corporate globalism dotting the landscape with McDonalds and filling the airwaves with Disney. Recently, protesters have been massing in the streets every few months against the system they see embodied in the WTO, the IMF and the World Bank. Each time this happens, commentators point out that the protesters present a bewildering array of demands. Nevertheless it would not be too much of an oversimplification to say that in a certain way all their demands oppose the three facets of American hegemony: its military power, its market power, and its power to influence other countries’ political agendas and cultural ideas.

Thus global America is indeed highly controversial. European intellectuals have also criticized it deeply (see Bohrer and Scheel 2000, or Bourdieu and Wacquart 1999). But is Europe an entity with a competing vision? Or, to be harsh, does it have a vision at all? Do Europeans want, for example, to expand to include Eastern Europe and Russia? Or do they want to draw a line and ‘Latin-Americanize’ these countries? Do Europeans have any strong feelings that are not inspired by fear – fear of losing their national sovereignty, a decline in their quality of life, a drop in their global clout? There is some justification in saying that Europe's lack of a positive vision leaves the USA with a world-view monopoly, although it is surely a great irony that the United States – a republic whose individual citizens are so relatively lacking in xenophobia and arrogance – can feel comfortable presenting itself as if it were a missionary to the heathens.

In this chapter I would like to clarify some conceptual oppositions. My claim is that the concept of Americanization is based on a national understanding of globalization. The concept of cosmopolitanization, by contrast, is an explicit attempt to overcome this ‘methodological nationalism’ and produce concepts capable of reflecting a newly transnational world.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Global America?The Cultural Consequences of Globalization, pp. 15 - 29Publisher: Liverpool University PressPrint publication year: 2003