Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Contributors

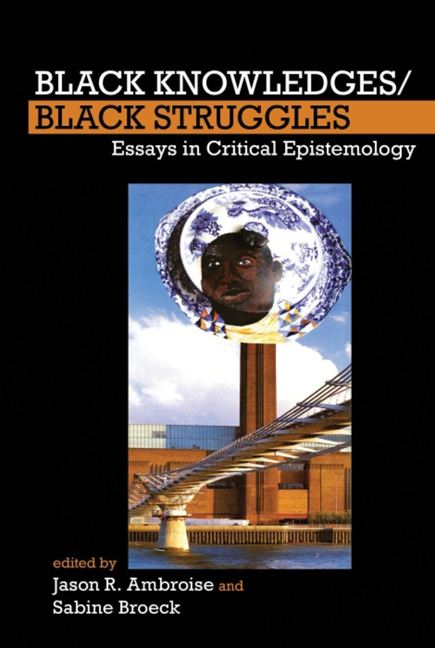

- 1 Black Knowledges/Black Struggles: An Introduction

- 2 “Come on Kid, Let's Go Get the Thing”: The Sociogenic Principle and the Being of Being Black/Human

- 3 Respectability and Representation: Black Freemasonry, Race, and Early Free Black Leadership

- 4 Ethno-Class Man and the Inscription of “the Criminal”: On the Formation of Criminology in the USA

- 5 Dehumanization, the Symbolic Gaze, and the Production of Biomedical Knowledge

- 6 Performing Scientificity: Race, Science, and Politics in the USA and Germany after the Second World War

- 7 Imaginary Black Topographies: What are Monuments For?

- 8 The Ceremony Found: Towards the Autopoetic Turn/Overturn, its Autonomy of Human Agency and Extraterritoriality of (Self-)Cognition

- Works Cited

- Index

7 - Imaginary Black Topographies: What are Monuments For?

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Contributors

- 1 Black Knowledges/Black Struggles: An Introduction

- 2 “Come on Kid, Let's Go Get the Thing”: The Sociogenic Principle and the Being of Being Black/Human

- 3 Respectability and Representation: Black Freemasonry, Race, and Early Free Black Leadership

- 4 Ethno-Class Man and the Inscription of “the Criminal”: On the Formation of Criminology in the USA

- 5 Dehumanization, the Symbolic Gaze, and the Production of Biomedical Knowledge

- 6 Performing Scientificity: Race, Science, and Politics in the USA and Germany after the Second World War

- 7 Imaginary Black Topographies: What are Monuments For?

- 8 The Ceremony Found: Towards the Autopoetic Turn/Overturn, its Autonomy of Human Agency and Extraterritoriality of (Self-)Cognition

- Works Cited

- Index

Summary

When I was in Paris a few months ago, I came across a delightful little guidebook about London. It lists nearly 300 places of interest. These, it claims, range from the National Gallery to “gruesome” Old St Thomas's operating theater, and from ancient Charterhouse to modern Canary Wharf. I was glad to see that the publishers had included most of the important landmarks, signaling the contribution made by Africans of the Black Diaspora to this great and crazy city. Right at the beginning they illustrate the black-and-white patterns across the clock face of Big Ben at the Houses of Parliament. It is good because they are easily missed, as they are only visible on hot days. The guidebook is not so great on the public holidays and African festivals staged by the people of fifty-two countries, but each sight mentioned is cross referenced to its own full entry.

In the following narrative I will share with you some examples of this guidebook's texts and a random selection of some of the monuments.

London

Whitehall and Westminster have been at the center of political and religious power in England for 1,000 years. Looking down Whitehall towards Big Ben is a statue of Oliver Cromwell on horseback, he hails Septimio Severo – African ruler of the Roman Empire from 193 to 211 CE – who spent time in England quelling revolts. It has to be noted, however, that the memorial garden for the African governor of the Roman province of Britannia, Quintus Lollius Urbicus, has never been replaced since it was destroyed during the Second World War.

Piccadilly is the main artery of the West End. Once called Portugal Street, it acquired its present name from the ruffs or pickadils worn by seventeenth-century slave servants and their aristocratic dandy-owners, who lived in the surrounding residences. The African contribution to style and dress is forever memorialized in the shop signs and iron-work of Piccadilly Arcade itself.

After nearly a century of debate about what to do with the patch of land in front of Apsley House, Wellington Arch, designed by Decimus Burton, was erected in 1828.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Black Knowledges/Black StrugglesEssays in Critical Epistemology, pp. 170 - 183Publisher: Liverpool University PressPrint publication year: 2015