Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- List of Contributors

- Acknowledgments

- Note on the Romanization of Chinese

- Introduction

- I FILM IN THE PEOPLE'S REPUBLIC

- II FILM IN TAIWAN AND HONG KONG

- 5 Remapping Taipei

- 6 The Ideology of Initiation

- 7 The Return of the Father

- 8 Border Crossing

- 9 Two Films from Hong Kong

- Chronologies

- Glossary

- Scholarly Works on Chinese Filmmaking in the 1980s

- Index

9 - Two Films from Hong Kong

Parody and Allegory

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 June 2012

- Frontmatter

- Contents

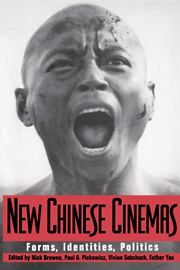

- List of Illustrations

- List of Contributors

- Acknowledgments

- Note on the Romanization of Chinese

- Introduction

- I FILM IN THE PEOPLE'S REPUBLIC

- II FILM IN TAIWAN AND HONG KONG

- 5 Remapping Taipei

- 6 The Ideology of Initiation

- 7 The Return of the Father

- 8 Border Crossing

- 9 Two Films from Hong Kong

- Chronologies

- Glossary

- Scholarly Works on Chinese Filmmaking in the 1980s

- Index

Summary

“Films from Hong Kong” – the phrase establishes an almost immediate association with mass entertainment. For years the Hong Kong film industry was dominated by two tycoons: Run Run Shaw (Shao Yifu) and Raymond Chow (Zhou Wenhuai), whose moneymaking “factory productions” have become trademarks for what may be called typical Hong Kong movies. Roughly, I would divide them into two basic subgenres – the “hardcore” gong fu, or martial arts, movie in a pseudohistorical setting or its contemporary counterpart, the gangster film whose obvious mass appeal is violence, and the “softcore” sexual or romantic comedy featuring a beautiful actress/songstress singing the obligatory number of songs. In the United States, the two types of film often form a double-feature presentation at the local Chinese cinema on a Saturday night. (It was in fact on such a typical evening in San Francisco's Chinatown that I discovered Rouge [Yanzhi kou, 1987], one of the surprises of artistic filmmaking disguised as a “softcore” comedy, a film I will discuss in this essay.)

It is not my intention here to give a conventional sociological analysis of these two subgenres as typical products of Hong Kong's urban popular culture. In recent years, the Hong Kong film has undergone some drastic transformations, and no simple catchall phrase like “popular entertainment” or the usual division between the “low-brow” commercial movie and the “high-brow” art film is likely to do justice to its complexities of form and content.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- New Chinese CinemasForms, Identities, Politics, pp. 202 - 216Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 1994

- 1

- Cited by