Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Of People, Places, and Parlance

- The Pre-Modern Period

- The Age of invention

- 5 Hogarth Engraving

- 6 Lithograph

- 7 Morse Telegraph

- 8 Singer Sewing Machine

- 9 Uncle Tom's Cabin

- 10 Corset

- 11 A.G. Bell Telephone

- 12 Light Bulb

- 13 Oscar Wilde Portrait

- 14 Kodak Camera

- 15 Kinetoscope

- 16 Deerstalker Hat

- 17 Paper Print

- Modern Times

- The Consumption Age

- The Digital Now

- About The Contributors

7 - Morse Telegraph

from The Age of invention

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 12 June 2019

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Of People, Places, and Parlance

- The Pre-Modern Period

- The Age of invention

- 5 Hogarth Engraving

- 6 Lithograph

- 7 Morse Telegraph

- 8 Singer Sewing Machine

- 9 Uncle Tom's Cabin

- 10 Corset

- 11 A.G. Bell Telephone

- 12 Light Bulb

- 13 Oscar Wilde Portrait

- 14 Kodak Camera

- 15 Kinetoscope

- 16 Deerstalker Hat

- 17 Paper Print

- Modern Times

- The Consumption Age

- The Digital Now

- About The Contributors

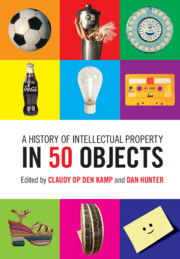

Summary

ON 24 MAY 1844, Samuel Finley Breese Morse tapped out the first message on the first fully operational electro-magnetic telegraph line: “What hath Godwrought!” Reflecting his deeply held religious convictions, Morse chose a line from the Bible, which he sent in the now-famous dot-and-dash transmission code he also invented, the eponymous “Morse Code.” One might accuse Morse of hyperbole in this transmission, but his invention of the electro-magnetic telegraph was a radical innovation that fundamentally transformed human communication. It was part of a wide-ranging upheaval in early 19th-century American society, in a country that was transforming itself from a primarily agrarian economy based on the Eastern seaboard to one that stretched across the continent with a fast-growing industrial and commercial economy, driven by technological innovation that dazzled world representatives when displayed in 1851 at the Crystal Palace Exhibition in London.

At the Crystal Palace, Morse's telegraph was included along with other American innovations, such as Eli Whitney's cotton gin, Samuel Colt's repeating firearm, Charles Goodyear's vulcanized rubber, and Cyrus McCormick's mechanized reaper. Together these inventions caused a radical technological, social, and economic transformation of American life in the 19th century. Yet, the telegraph was unique if only because it was the product of cutting-edge discoveries in both mechanics and science (called “natural philosophy” at the time) that created an immediately practical benefit unknown before in human history—fast and efficient communication over vast distances.

Americans were enthralled with what they called the “Lightning Line” and with the man who invented it, whom they called the “Lightning Man.” One newspaper proclaimed that the telegraph's instantaneous communication “annihilated space and time.” The New York Sun waxed poetic that Morse's telegraph was “the greatest revolution of modern times and indeed of all time, for the amelioration of Society.” Another newspaper embraced Morse's own nationalist chauvinism in calling the telegraph “the most wonderful climax of American inventive genius”.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- A History of Intellectual Property in 50 Objects , pp. 64 - 71Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2019