Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Preface

- Manuscript Collections Cited

- List of Abbreviations

- Slavery in White and Black

- Introduction

- 1 The Impending Collapse of Capitalism

- 2 Hewers of Wood, Drawers of Water

- 3 Travelers to the South, Southerners Abroad

- 4 The Squaring of Circles

- 5 The Appeal to Social Theory

- 6 Perceptions and Realities

- Afterword

- Index

6 - Perceptions and Realities

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 June 2012

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Preface

- Manuscript Collections Cited

- List of Abbreviations

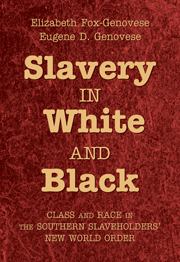

- Slavery in White and Black

- Introduction

- 1 The Impending Collapse of Capitalism

- 2 Hewers of Wood, Drawers of Water

- 3 Travelers to the South, Southerners Abroad

- 4 The Squaring of Circles

- 5 The Appeal to Social Theory

- 6 Perceptions and Realities

- Afterword

- Index

Summary

How can a man be recalled to salvation, when he has none to restrain him, and all mankind to urge him on?

—SenecaAs self-anointed paternalists, slaveholders felt sorely put upon as scapegoats for the inevitable condition of laboring people. Arguing that no social system could be judged fairly by its accompanying evils, E. J. Pringle of South Carolina accused Harriet Beecher Stowe of being “unjust” to the South. No essential institution – neither Christian churches nor the family – could pass that test. Defenders of slavery appealed to Jesus: “The poor always ye have with you; but me ye have not always” (John, 12:8). Northerners and Southerners respected private property, but, Pringle asked, who could deny that its uses oppressed the poor? Man's inherent sinfulness marred every divinely sanctioned institution. Society would not need a criminal code if any system “could correct all the evil tendency of man's nature.” In 1856 the Presbyterian Reverend Frederick A. Ross of Alabama described Uncle Tom's Cabin as “that splendid bad book” – “splendid in its genius over which I have wept, and laughed, and got mad.” Ross told the New School General Assembly in New York in 1856 that bad theology, bad morals, and distortions of southern life were having a corrosive influence in the North and abroad. “Every fact in Uncle Tom's Cabin has occurred in the South,” but there is greater cruelty toward women and the poor in New York and Boston than in the South.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Slavery in White and BlackClass and Race in the Southern Slaveholders' New World Order, pp. 234 - 288Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2008