Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of contributors

- Acknowledgements

- Foreword (David Langslow)

- PART I THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

- PART II EARLY LATIN

- PART III CLASSICAL LATIN

- PART IV EARLY PRINCIPATE

- 17 Petronius' linguistic resources

- 18 Parenthetical remarks in the Silvae

- 19 Colloquial Latin in Martial's epigrams

- 20 Current and ancient colloquial in Gellius

- 21 Forerunners of Romance -mente adverbs in Latin prose and poetry

- PART V LATE LATIN

- Abbreviations

- References

- Subject index

- Index verborum

- Index locorum

21 - Forerunners of Romance -mente adverbs in Latin prose and poetry

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 04 April 2011

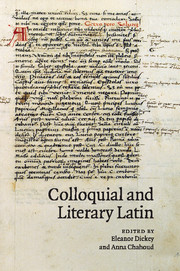

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of contributors

- Acknowledgements

- Foreword (David Langslow)

- PART I THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

- PART II EARLY LATIN

- PART III CLASSICAL LATIN

- PART IV EARLY PRINCIPATE

- 17 Petronius' linguistic resources

- 18 Parenthetical remarks in the Silvae

- 19 Colloquial Latin in Martial's epigrams

- 20 Current and ancient colloquial in Gellius

- 21 Forerunners of Romance -mente adverbs in Latin prose and poetry

- PART V LATE LATIN

- Abbreviations

- References

- Subject index

- Index verborum

- Index locorum

Summary

INTRODUCTION

As a rule of thumb linguistic change typically starts in the colloquial registers of a given language and gradually spreads to other segments of language use. High-level literature and legal texts tend to be last to incorporate linguistic innovations. The shift from object-before-verb (OV) to verb-before-object (VO) structures, for example, was first manifest in the more colloquial Latin texts and only spread to other registers at a later stage. The honorand of this Festschrift has analysed this change on various occasions and already in 1977 stated that ‘in spoken Latin of the informal varieties VO was already established as the unmarked order, but…OV was preferred in literary Latin.… It is well-established that formal and informal codes in any language differ radically’ (Adams 1976b: 97). Similarly, other major linguistic changes first manifest themselves in our sources of colloquial Latin: case loss and the spread of prepositions, the loss of other inflected forms in favour of right-branching analytic forms, the spread of subordinate clauses with conjunctions and finite verbs replacing accusative with infinitive and participial constructions, and so forth.

The same pattern is found in other languages as well and at all times. The eventual morphological loss in today's French of the passé défini (passé simple), for example, which goes back to the Latin perfective paradigm (Fr. je louai < Lat. laudavi), is now almost complete and can be traced in the twentieth century in the various written registers.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Colloquial and Literary Latin , pp. 339 - 354Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2010

- 4

- Cited by