Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Introduction: Over-exposed, Under-exposed: Harriet Jacobs and Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl

- “I Disguised My Hand”: Writing Versions of the Truth in Harriet Jacobs's Incidents in the life of a Slave Girl and John Jacobs's “A True Tale of Slavery”

- Through Her Brother's Eyes: Incidents and “A True Tale”

- Resisting Incidents

- Manifest in Signs: The Politics of Sex and Representation in Incidents in the life of a Slave Girl

- Earwitness: Female Abolitionism, Sexuality, and Incidents in the life of a Slave Girl

- Reading and Redemption in Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl

- Harriet Jacobs, Frederick Douglass, and the Slavery Debate: Bondage, Family, and the Discourse of Domesticity

- Motherhood Beyond the Gate: Jacobs's Epistemic Challenge in Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl

- “This Poisonous System”: Social Ills, Bodily Ills, and Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl

- Carnival Laughter: Resistance in Incidents

- Harriet Jacobs, Henry Thoreau, and the Character of Disobedience

- The Tender of Memory: Restructuring Value in Harriet Jacobs's Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl

- Conclusion: Vexed Alliances: Race and Female Collaborations in the Life of Harriet Jacobs

- List of Contributors

- Index

- CAMBRIDGE STUDIES IN AMERICAN LITERATURE AND CULTURE

Harriet Jacobs, Henry Thoreau, and the Character of Disobedience

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 22 January 2010

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Introduction: Over-exposed, Under-exposed: Harriet Jacobs and Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl

- “I Disguised My Hand”: Writing Versions of the Truth in Harriet Jacobs's Incidents in the life of a Slave Girl and John Jacobs's “A True Tale of Slavery”

- Through Her Brother's Eyes: Incidents and “A True Tale”

- Resisting Incidents

- Manifest in Signs: The Politics of Sex and Representation in Incidents in the life of a Slave Girl

- Earwitness: Female Abolitionism, Sexuality, and Incidents in the life of a Slave Girl

- Reading and Redemption in Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl

- Harriet Jacobs, Frederick Douglass, and the Slavery Debate: Bondage, Family, and the Discourse of Domesticity

- Motherhood Beyond the Gate: Jacobs's Epistemic Challenge in Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl

- “This Poisonous System”: Social Ills, Bodily Ills, and Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl

- Carnival Laughter: Resistance in Incidents

- Harriet Jacobs, Henry Thoreau, and the Character of Disobedience

- The Tender of Memory: Restructuring Value in Harriet Jacobs's Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl

- Conclusion: Vexed Alliances: Race and Female Collaborations in the Life of Harriet Jacobs

- List of Contributors

- Index

- CAMBRIDGE STUDIES IN AMERICAN LITERATURE AND CULTURE

Summary

Civil disobedience, or the public expression of dissatisfaction with the state through violation of particular laws, has assumed a central, familiar role in American politics. In the struggle for black liberation, civil disobedience has been upheld both as an organizing principle of action and as a crucial remedy for the failure of legal systems to secure necessary changes in their own structures. As Martin Luther King, Jr., observed in his 1963 letter written from the Birmingham Cityjail, the purpose of the civil disobedient is to “create a situation so crisis-packed that it will inevitably open the door to negotiation.” In the aftermath of the 1960s, a general description of civil disobedience has emerged in theoretical debate on the subject, but political philosophers have for the most part neglected questions of cultural context. They have failed to recognize a diverse field of conceptual possibilities: the untold variety of ways in which acts of disobedience have been rendered and critiqued in works of American literature.

In what follows, I compare two widely different nineteenth-century models of disobedience, both of which were constructed in response to a constitutional crisis arising from the fact of slavery in America. One model is Thoreau's famous example at Concord, which he describes in his 1849 essay “On the Duty of Civil Disobedience,” originally published under the title “Resistance to Civil Government.” The other is drawn from Harriet Jacobs's fictionalized slave narrative entitled Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, published in 1861.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

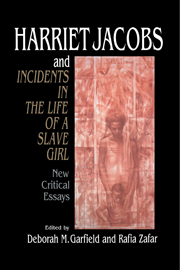

- Harriet Jacobs and Incidents in the Life of a Slave GirlNew Critical Essays, pp. 233 - 250Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 1996