Book contents

- Ecology, Conservation and Management of Wild Pigs and Peccaries

- Ecology, Conservation and Management of Wild Pigs and Peccaries

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Contributors

- Foreword

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Part I Evolution, Taxonomy, and Domestication

- Part II Species Accounts

- 6 Sulawesi Babirusa Babyrousa celebensis (Deninger, 1909)

- 7 Moluccan Babirusa Babyrousa babyrussa (Linnaeus, 1758)

- 8 Togian Babirusa Babyrousa togeanensis (Sody, 1949)

- 9 Common Warthog Phacochoerus africanus (Gmelin, 1788)

- 10 Desert Warthog Phacochoerus aethiopicus (Pallas, 1766)

- 11 Forest Hog Hylochoerus meinertzhageni (Thomas 1904)

- 12 Bushpig Potamochoerus larvatus (F. Cuvier, 1822)

- 13 Red River Hog Potamochoerus porcus (Linnaeus, 1758)

- 14 Visayan Warty Pig Sus cebifrons (Heude, 1888)

- 15 Philippine Warty Pig Sus philippensis (Nehring, 1886)

- 16 Mindoro Warty Pig Sus oliveri (Groves, 1997)

- 17 Palawan Bearded Pig Sus ahoenobarbus (Huet, 1888)

- 18 Bearded Pig Sus barbatus (Müller, 1838)

- 19 Sulawesi Warty Pig Sus celebensis (Muller & Schlegel, 1843)

- 20 Javan Warty Pig Sus verrucosus (Boie, 1832) and Bawean Warty Pig Sus blouchi (Groves and Grubb, 2011)

- 21 Eurasian Wild Boar Sus scrofa (Linnaeus, 1758)

- 22 Pygmy Hog Porcula salvania (Hodgson, 1847)

- 23 Chacoan Peccary Catagonus wagneri (Rusconi, 1930)

- 24 Collared Peccary Pecari spp. (Linnaeus, 1758)

- 25 White-lipped Peccary Tayassu pecari (Link, 1795)

- Part III Conservation and Management

- Index

- References

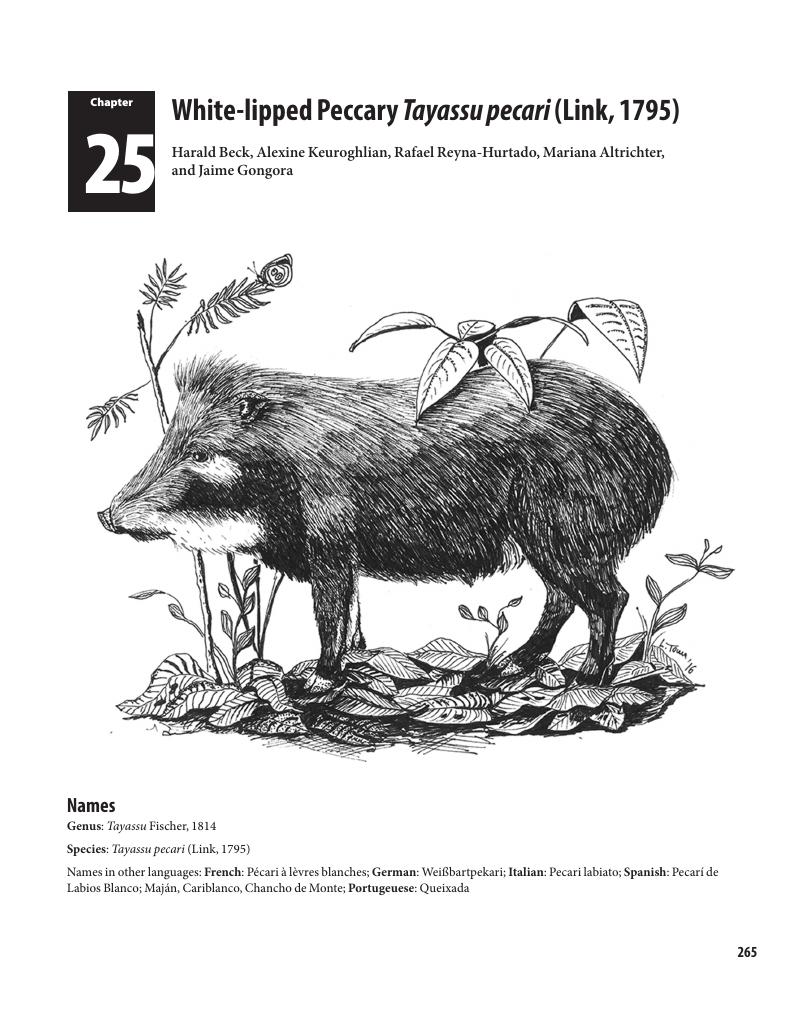

25 - White-lipped Peccary Tayassu pecari (Link, 1795)

from Part II - Species Accounts

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 21 November 2017

- Ecology, Conservation and Management of Wild Pigs and Peccaries

- Ecology, Conservation and Management of Wild Pigs and Peccaries

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Contributors

- Foreword

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Part I Evolution, Taxonomy, and Domestication

- Part II Species Accounts

- 6 Sulawesi Babirusa Babyrousa celebensis (Deninger, 1909)

- 7 Moluccan Babirusa Babyrousa babyrussa (Linnaeus, 1758)

- 8 Togian Babirusa Babyrousa togeanensis (Sody, 1949)

- 9 Common Warthog Phacochoerus africanus (Gmelin, 1788)

- 10 Desert Warthog Phacochoerus aethiopicus (Pallas, 1766)

- 11 Forest Hog Hylochoerus meinertzhageni (Thomas 1904)

- 12 Bushpig Potamochoerus larvatus (F. Cuvier, 1822)

- 13 Red River Hog Potamochoerus porcus (Linnaeus, 1758)

- 14 Visayan Warty Pig Sus cebifrons (Heude, 1888)

- 15 Philippine Warty Pig Sus philippensis (Nehring, 1886)

- 16 Mindoro Warty Pig Sus oliveri (Groves, 1997)

- 17 Palawan Bearded Pig Sus ahoenobarbus (Huet, 1888)

- 18 Bearded Pig Sus barbatus (Müller, 1838)

- 19 Sulawesi Warty Pig Sus celebensis (Muller & Schlegel, 1843)

- 20 Javan Warty Pig Sus verrucosus (Boie, 1832) and Bawean Warty Pig Sus blouchi (Groves and Grubb, 2011)

- 21 Eurasian Wild Boar Sus scrofa (Linnaeus, 1758)

- 22 Pygmy Hog Porcula salvania (Hodgson, 1847)

- 23 Chacoan Peccary Catagonus wagneri (Rusconi, 1930)

- 24 Collared Peccary Pecari spp. (Linnaeus, 1758)

- 25 White-lipped Peccary Tayassu pecari (Link, 1795)

- Part III Conservation and Management

- Index

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Ecology, Conservation and Management of Wild Pigs and Peccaries , pp. 265 - 276Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2017

References

- 5

- Cited by