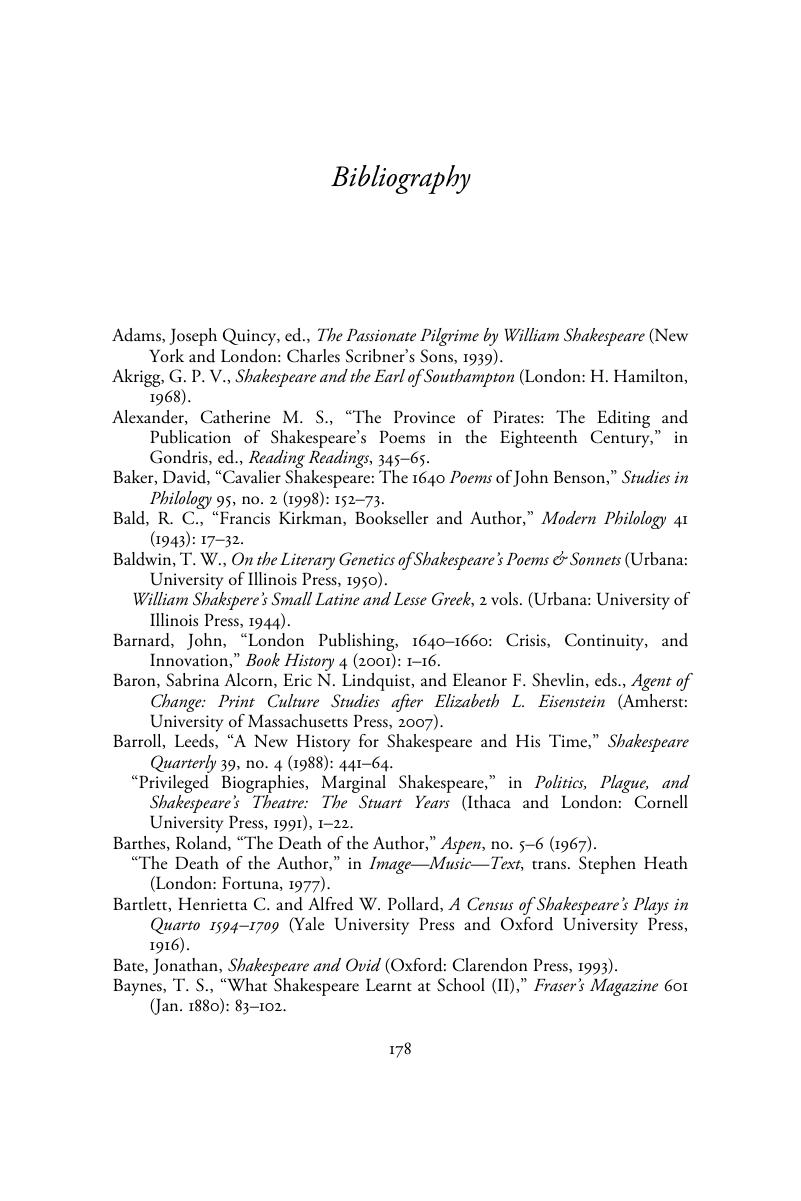

Bibliography

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 February 2016

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Selling ShakespeareBiography, Bibliography, and the Book Trade, pp. 178 - 193Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2016