Supporting adolescents toward healthy digital media use and digital citizenship more broadly “takes a village” (Hollandsworth et al., Reference Hollandsworth, Dowdy and Donovan2011). Chapters in this volume have touched on different aspects of digital media use and adolescent mental health, pointing to the importance of clinical intervention. Schools are another crucial entry point for delivery of support and prevention of future mental health difficulties. Educators have considerable reach to a captive audience of youth. Examining why, what, and how they teach students about digital media use and well-being is vital. In this chapter, we review leading K–12 digital media curricula that aim to teach students how to lead healthy digital lives. We outline the content and pedagogical approaches present in these materials and distill a set of learning goals apparent across curricular resources: critical awareness, self-reflection, and behavioral change. Given the relative absence of external evaluations of school-based interventions, we draw on relevant research to suggest both promising directions and key questions for future research.

Why do schools take on healthy digital media use and digital citizenship more broadly as a topic of instruction and intervention? At least four distinct drivers are arguably at play: problems, parents, precedent, and policies. First, problems: Digital and social media are meaningful venues for young people’s learning and lives beyond the classroom (Ito et al., Reference Ito, Odgers and Schueller2020). As adolescents use apps for peer connection, there are meaningful upsides but also inevitable conflicts. Conflicts that start online routinely spill over into schools, creating problems educators must solve through reactive sanctions, proactive classroom lessons, or both (Hinduja & Patchin, Reference Hinduja and Patchin2011). Other problems that educators feel pressed to solve include in-school device misuse, distraction, and inattention in class due to media-linked sleep deprivation (e.g., Klein, Reference Klein2020; Sparks, Reference Sparks2013). Second, parents are searching for support as they raise the first generation of digital youth (Palfrey & Gasser, Reference Palfrey and Gasser2011). They may turn to schools for guidance, or even demand that schools intervene when issues like digital drama or cyberbullying cases involve their children and fellow students. Third, precedent: in many schools, there is a long history of teaching relevant topics, including media literacy, news and information literacy, and health and wellness. Teachers of these topics have naturally (even if reluctantly) had to incorporate digital media into their class content in order to keep it relevant. Fourth, policies: The above factors have triggered school device policies to which enrolled students must consent, especially in schools with one-to-one laptop or tablet programs. However, schools are not the only policy drivers. Increasingly, schools themselves are subject to state policies that suggest or even mandate teaching of digital topics (Media Literacy Now, 2020; Phillips & Lee, Reference Phillips and Lee2019). For example, in 2019, the state of Texas passed legislation requiring school districts to incorporate digital citizenship (defined as “appropriate, responsible, and healthy online behavior”) into curricula and instruction (Media Literacy Now, 2020, p. 12).

In sum, problems, parents, precedent, and policies create a demand for resources to support digital citizenship and healthy digital media use. Comprehensive curricula and other resources for schools emerged in the 2000s in response, initially with a focus on internet safety and then with the expanded purview and framing of “digital citizenship” (Cortesi et al., Reference Cortesi, Hasse, Lombana-Bermudez, Kim and Gasser2020). While these curricula center on the Internet and social media, they build on a longer tradition of media literacy education (MLE). MLE has long advocated competences for informed and critical reflection about media. Through MLE, students develop a core recognition that media messages are constructed and a related understanding of the persuasion techniques used in ads and other mass media (Hobbs, Reference Hobbs2010). Now expanded to encompass “‘the digital,” contemporary MLE spans skills and knowledge for critical reflection about digital content (i.e., posts produced by others and oneself) as well as traditional mass media content. Protection and empowerment are dual motivations for digital and media literacy education: building essential literacies to protect youth from potential risks (e.g., harm to their psychological well-being) and empower them to leverage media benefits (e.g., for learning, social connection) (Hobbs, Reference Hobbs, Blumberg and Brooks2017).

Digital citizenship encompasses all of the skills for participation in a digital world – personally, socially, and civically – including essential “new media literacies” (Cortesi et al., Reference Cortesi, Hasse, Lombana-Bermudez, Kim and Gasser2020; Jenkins, Reference Jenkins2009). Mike Ribble and Gerald Bailey, who were among the first to use the term digital citizenship, named digital health and wellness as a key aspect of digital citizenship in the first edition of their book, Digital Citizenship in Schools (Reference Ribble and Bailey2007). At the time, they emphasized physical health and framed the topic in relation to protection from harms like carpal tunnel, poor posture, and eye strain through improper ergonomics. Ribble and Bailey also referenced psychological well-being and internet addiction, which they acknowledged as “another aspect of digital safety that has not received the attention it deserves” (p. 32).

Psychological well-being is no longer at the margins of discussions about digital life. In recent years, technology overuse and psychological well-being have been a steady focus in both public discourse and academic research. These topics have also been a source of considerable debate among researchers. As discussed throughout this volume, research currently converges around a recognition that young people are differentially susceptible to digital media impacts (See Subrahmanyam & Michikyan, Chapter 1 in this volume; Valkenburg, Chapter 2 in this volume). Individual, social, and contextual risk factors present in adolescents’ offline lives are often mirrored or amplified as they use digital media. For example, adolescents who have mental health challenges, those who are victimized, those who have limited family resources, and those who are surrounded by more offline violence in their communities all face digital risks that can impact their health and well-being (e.g., see Nesi et al., Reference Nesi, Wolff and Hunt2019; Odgers, Reference Odgers2018; Patton et al., Reference Patton, Eschmann, Elsaesser and Bocanegra2016; Underwood & Ehrenreich, Reference Underwood and Ehrenreich2017). And yet, digital media use can also reduce or mitigate offline risk (Ito et al., Reference Ito, Odgers and Schueller2020). Youth who are ostracized offline can find supportive community connections and resources for coping and recovery online.

The design features of technologies also shape their use in ways that matter for adolescent health and well-being. Today’s apps and devices are designed with features that are intentionally tested, iterated, and deployed to hold users’ attention (Center for Humane Technology, 2020a). For example, social media apps provide an endless stream of intermittent rewards (Alter, 2017; Center for Humane Tech, 2020a, 2020b). Features like infinite scrolling remove natural stopping cues. Default push notifications interrupt other activities. And metrics like Snapchat streaks capitalize on social reciprocity. These features leverage psychological vulnerabilities to create powerful habits loops and even, in some cases, behavioral addictions (Alter, Reference Alter2017).

Although individual youth are differentially vulnerable to these design tactics, from a developmental standpoint all adolescents are in a position of vulnerability given their sensitivity to social feedback and peer acceptance (Steinberg, Reference Steinberg2014). At the same time, the neural bases for impulse control are still developing (Dahl, Reference Dahl2004; Tamm et al., Reference Tamm, Menon and Reiss2002). Thus, contemporary adolescents are in a precarious position: the rewards social media offer are compelling and their capacities for self-regulation are not yet fully mature. Given that avoiding digital technology all together is neither desirable nor practical, learning how to use it in ways that promote rather than diminish health and well-being is arguably crucial. Schools represent an opportune context for this learning given their reach to a wide audience of youth and the frequent role of schools (whether realized or aspirational) in providing guidance related to matters of health and well-being (e.g., health class and drug and alcohol prevention efforts).

Digital Citizenship and Related Curricula for School-Based Approaches

To examine existing school-based approaches to support healthy digital technology use, we conducted a two-phase review of available curricula. First, we identified and reviewed leading digital citizenship programs and lessons (Table 15.1). Second, we conducted a closer examination of curricular resources identified in Step 1 that addressed healthy digital habits.

Table 15.1 Digital citizenship curricula and resources

| Topics addressed1 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Program | Resource structure | Target grade levels | Fee structure | Cyberbullying, drama | Identity, dig. footprints | Info. quality, news literacy | Privacy, safety | Sexting | Communication,Friendship | Violent and/or explicit content | Digital habits, media balance |

| Be Internet Awesome - Digital Safety & Citizenship Curriculum (Google) | Curriculum of 5 units with 26 lesson activities and an online game (Interland) | 2–6 | Free | ||||||||

| Cyberbalance and Healthy Content Choices Curriculum (iKeepSafe) | 3 lessons (1 lesson for students in grades K–5, 2 lessons for grades 7–12) with YouTube playlists for each lesson and an illustrated e-book series for elementary students | K–12 | Free | ||||||||

| Cyber Civics Classroom Curriculum (CyberWise) | 3-year middle school curriculum of 50+ lessons organized in 6–8 units per grade level | 6–8 | Paid (pricing based on number of students) | ||||||||

| Digital Citizenship Curriculum (Common Sense Education) | Curriculum of 50+ lessons across 6 topical areas with ~1–2 lessons per topic per grade from K–12 and several interactive online games | K–12 | Free | ||||||||

| Digital Citizenship+ Resource Platform (Berkman Klein Center at Harvard University) | Resource library of lessons, infographics, videos, podcasts, and guides spanning 17 topics | 6–12 | Free | ||||||||

| Digital Citizenship Collection (BrainPOP) | 20 self-guided, interactive online lessons; curriculum for grades 3–5 provides additional lesson supports and sequencing for a selection of these lessons | 3–12 | Paid subscription | ||||||||

| Digital Citizenship (Digital Futures Initiative) | 3 lessons (1 lesson per grade for grades 7–9) each touching briefly on a range of digital topics; required educator training course | 7–9 | Free | ||||||||

| Digital Literacy & Citizenship Curriculum (Google & iKeepSafe) | Curriculum of 3 workshop lesson plans | 6–8 | Free | ||||||||

| DQ (DQ Institute) | 8-week self-directed online digital citizenship course via an interactive adventure game that builds and scores “Digital IQ” | 3–6 | Free basic plan, paid premium plan | ||||||||

| Human Relations Media | Collection of 19 streamable videos with corresponding teacher guides, each on a different topic related to social media and youth | K–12 | Paid (each video purchased separately) | ||||||||

| InCTRL (Cable Impacts Foundation) | 7 lessons, each on a different topic | 4–8 | Free | ||||||||

| Media Education Lab (University of Rhode Island) | Resource library with an assortment of media literacy lesson guides, curricula, and multi-media resources (e.g., podcasts, magazines) | Not specified | Includes both free and paid resources | ||||||||

| Media Lessons and Resources (MediaSmarts, Canada’s Centre for Digital and Media Literacy) | Resource library with 50+ lessons searchable by grade level and/or topic | K–12 | Free | ||||||||

| Screenshots Curriculum (Media Power Youth) | Curriculum of 9 lessons organized as 3 units with corresponding podcast, videos, and PowerPoints (note: Media Power Youth’s after-school program was not included in this review) | 6–8 | Free and paid options | ||||||||

| NetSmartz (National Center for Missing & Exploited Children) | Four PowerPoint-based lessons on online safety (one each per grades K–2, 3–5, 6–8, 9–12); animated video series with lesson activities for K–3 (Into the Cloud); 3 elementary e-books with discussion guides | K–12 | Free | ||||||||

| News Literacy Project | E-learning platform (Checkology) with 13 lessons and other resources for teaching news literacy, including misinformation | 4–12 | Free | ||||||||

| The Digital Citizenship Handbook for School Leaders: Fostering Positive Interactions Online (Ribble & Park, 2019) | Book with a framework and progression chart that outlines 9 elements of digital citizenship and corresponding classroom activities | K–12 | Free tip sheet; book available for purchase | ||||||||

| Internet Safety (The Safe Side) | Week-long curriculum with 5 lessons (designed to be taught 1 per day) and an accompanying YouTube video | K–3 | Free | ||||||||

| Talks and Guidelines for Families & Educators (Center for Humane Technology) | Video-recorded presentation on persuasive technology; “Take Control” tech tips and strategies | Not specified; likely most relevant for 6–12 | Free (video of recorded talk available on Vimeo); paid guest speaker talks | ||||||||

| White Ribbon Week | 4 week-long curriculum units with 5 lessons each; designed for a whole-school approach where school takes on 1 topic per year, 1 lesson per day | K–5 | Paid (each unit purchased separately) | ||||||||

Notes: Shading key: dark grey = designated topic, covered in depth; light grey = topic mentioned or covered to some extent; white = not covered based on our review of resources.

In the first phase of our review, we identified 20 relevant programs through (1) Google search, (2) consultation with experts, (3) review of educator resource “round ups” (e.g., via Edutopia), and (4) a recent comprehensive report on digital citizenship frameworks and approaches (Cortesi et al., Reference Cortesi, Hasse, Lombana-Bermudez, Kim and Gasser2020). With one exception (Center for Humane Technology), all programs we reviewed are framed as curricula, lessons, and/or classroom resources designed for use in K–12 school contexts. All are described as resources for supporting digital media use, often under the label of “digital citizenship.” We did not examine programs related to coding or computer science skills, nor did we focus on programs that incorporate but do not center technology use (for example, programs focused on self-harm and suicide prevention that may also cover the role of online communities).

In Table 15.1, we outline for each program (as of Fall 2020) the structure and format of resources, target grade levels, fee structure, and whether each program provides explicit instruction on the following common digital citizenship topics: cyberbullying and drama; identity expression and digital footprints; information quality and news literacy; privacy and safety; sexting; friendship and communication; violent and/or explicit content; and healthy digital habits.

All of these topics are relevant to healthy digital media use and individual well-being. A few examples: Cyberbullying is linked to poor psychosocial functioning, increased likelihood of self-injury, and poor physical health, as well as diminished academic performance (Kowalski et al., Reference Kowalski, Giumetti, Schroeder and Lattanner2014). Certain types of sexting are associated with internalizing problems (depression/anxiety) and risky sexual health behaviors, particularly for younger adolescents (Mori et al., Reference Mori, Temple, Browne and Madigan2019). Self-expression and digital footprints are intertwined with identity development, which is a key task of adolescence and healthy psychosocial development for all youth (Davis & Weinstein, Reference Davis, Weinstein and Wright2017). Depressed adolescents also report online self-expression practices like oversharing, “stressed posting,” and disclosing their own mental health issues (Nesi et al., Reference Nesi, Wolff and Hunt2019; Radovic et al., Reference Radovic, Gmelin, Stein and Miller2017). These practices may amplify short-term risks (e.g., because they contribute algorithmic inputs that suggest an interest in depressogenic or triggering content) and create lasting digital footprints with sensitive mental health information. Graphic, violent content in video games and pornography is a persistent focus of adult concern, though causal impacts on youth health and behavior remain a source of contention among researchers (Anderson, Reference Anderson2003; Ferguson, Reference Ferguson2020; Gentile, Reference Gentile2011; Kohut & Štulhofer, Reference Kohut and Štulhofer2018).

Available school-based programs that address topics relevant to adolescent well-being vary considerably in their approaches. Some programs provide brief coverage of a topic, while others offer multiple lessons for a deeper dive. Some have one resource set that is designed for applicability to students across multiple grade levels, while others are grade differentiated. Programs that have resources framed as applicable across multiple grade levels include: The Center for Humane Technology, which currently has a single signature video-recorded presentation and related technology tips and strategies; Google’s Be Internet Awesome curriculum, which has a collection of lessons that are all framed as best-suited for students in grades 2–6; and White Ribbon Week, which also uses the same lessons across a grade band (in their case, all elementary school grade levels). Other programs are grade differentiated: Common Sense Education, for example, has different lessons aligned to every year of school from kindergarten through 12th grade and CyberWise has lessons for each year of middle school. Across programs, some lessons are structured around a lecture-style presentation while others are interactive and use discussion questions, writing prompts, or hypothetical scenarios to engage students through more constructivist approaches (where learners actively make meaning of content and their personal connections to it). Most have mixed-media elements and a few have their own full-fledged online games (e.g., Be Internet Awesome, Common Sense Education, and DQ). Nearly all of the programs have educator tips, guides, or resources to support teaching and several have comprehensive professional development training (e.g., webinars, courses, and certification programs).

Even a brief review of the lessons also reveals considerable variation in how different programs approach the same topic. For example, with respect to cyberbullying, programs vary in how much time they allot to the topic (e.g., is cyberbullying a passing mention or the focus of multiple lessons?); in pedagogical approaches (e.g., do teachers provide students with strategies for dealing with cyberbullying and/or ask students to come up with their own ideas?); and – perhaps most crucially – in both implicit and explicit messages about the topic (e.g., are students primarily encouraged to be allies who stand with targets or to be upstanders who stand up to aggressors?). Each topic area listed in Table 15.1 could reasonably be the focus of a full review to examine these key messages and approaches and how they map to existing research. Given our focus in this chapter on healthy media use, we conducted a review of lessons that aim to promote healthy digital habits (i.e., those in the far-right column of the table, which is outlined and labeled “Digital Habits, Media Balance”).

A Closer Look at School-Based Lessons to Promote Healthy Digital Habits

The second phase of our review was a more focused examination of resources from across these programs that aim to promote healthy digital habits. To our knowledge, none of these lessons has yet been systematically evaluated. We therefore provide a descriptive review of what the available lessons teach about healthy technology use and how they approach this aim. All of the lessons we reviewed on healthy digital habits emphasize one or more of the following learning goals: (1) critical awareness of design features and/or psychological principles that shape technology use; (2) self-reflection on personal digital media use; and (3) strategies for behavioral change. In the following sections, we review these learning goals in turn. We provide examples of how each learning goal is approached in lessons about healthy digital media use, discuss how and why it might help promote healthy media use, and outline relevant questions for future research to build an evidence base for school-based approaches.

Critical Awareness of Design Features and Psychological Principles

One recurring aim of lessons designed to promote healthy digital media use is critical awareness and understanding. These lessons metaphorically pull back the curtain and reveal to students how digital features and design can powerfully intersect with psychological processes to shape technology experiences. Lessons from all but one program included an emphasis on this kind of critical awareness. Examples include teaching students:

how platforms harness data to push tailored content and targeted ads based on interests and browsing history;

how features like infinite scroll and auto-play intentionally remove friction to make for seamless ongoing use;

how metrics, especially “likes” and “streaks,” play off motives related to social status and instincts for social reciprocity;

how social media contributes to highlight reels that are ripe for social comparison and contribute to a common experience of feeling bad when scrolling through a social media feed;

how social media apps and gaming platforms leverage variable rewards much in the same way as casino slot machines to create a compelling unconscious reward structure;

how social networks can function as echo chambers that distort perceptions;

how misinformation is presented in ways that look real and promote circulation;

how to recognize active versus passive uses of technology, which seem to differentially impact well-being; and

how digital features like notifications and/or content like pornography activate dopamine reward circuits.

How and why might this kind of learning promote healthy digital media use? In traditional media literacy education, students learn that media messages are constructed, and they learn to recognize and analyze techniques that influence persuasion (National Association for Media Literacy Education, 2007). Critical thinking is seen as key to “liberating the individual from unquestioning dependence on immediate cultural environment” (Brown, Reference Brown1998, p. 47). A meta-analysis of 51 traditional media literacy interventions indeed found significant positive effects on students’ knowledge and critical understanding (Jeong et al., Reference Jeong, Cho and Hwang2012). More recent experimental research demonstrated that teaching adolescents about “addictive” social media designs and their harmful effects can prompt enduring awareness of design features. It can also motivate young people's interest in regulating their social media use and in learning relevant strategies (Galla et al., Reference Galla, Choukas‐Bradley, Fiore and Esposito2021).

Jeong and colleagues’ meta-analysis of traditional media literacy interventions indicated that: a) passive teaching approaches (e.g., lecture-style) and interactive approaches (e.g., discussion, role playing, games) were both effective, b) that lessons could be successfully delivered by peers or by expert instructors, and c) interventions with a greater number of sessions tended to have larger effect sizes. These insights may prove relevant for curricula aiming to promote healthy digital media use. That is, students may similarly benefit from learning how digital tools and content are constructed and how these constructions influence perception and persuasion. While varied pedagogies and lesson contexts hold potential value, repeated lessons are likely more effective than isolated “one-and-done” approaches. That said, these are still open questions for research on digital habits interventions, and especially so given emerging evidence related to the value of single-session interventions for mental health (Schleider et al., Reference Schleider, Dobias, Sung and Mullarkey2020). Further questions include: Do passive versus interactive approaches change learning outcomes related to critical awareness about digital media? Which formats (expert instruction, peer-based, etc.) are most effective? Further, in terms of content, which digital design features and principles are most relevant to include in curricula? And more generally, there is the crucial question of efficacy: Does teaching for critical awareness indeed impact students’ digital technology experiences and – if so – how?

Available digital media lessons aim to help students identify features that unconsciously drive their technology use. In addition to building students’ knowledge, recognizing these features and design tactics may also motivate their desires to take action toward more control. However, critical understanding alone is likely an insufficient catalyst for behavioral change. Jeong et al.’s (Reference Jeong, Cho and Hwang2012) meta-analysis indicated that media literacy interventions seemed to have greater effects on knowledge-related outcomes than on behavior-related outcomes. Relatedly, research from behavioral economics suggests that even when people know a strategy is being used to “nudge” their behavior, this knowledge does not remove its effect (e.g., Bruns et al., Reference Bruns, Kantorowicz-Reznichenko, Klement, Luistro Johnson and Rahali2018). Thus, lessons designed to impact healthy digital media use are likely wise to include a focus on critical understanding, but such understanding may prove insufficient to successfully reroute digital habits.

Self-Reflection about Personal Digital Media Use

Self-reflection is a second prominent learning goal in lessons that target healthy digital media habits. This is driven by fundamentally interactive (rather than lecture-based) activities that typically direct students to consider some aspect of their personal digital media use. In existing lessons within the digital citizenship programs we reviewed, self-reflection ranged from open-ended brainstorming about personal tech habits to the use of more templatized tools for logs and tracking. Such tools differ in both structure and in the focal behaviors they prompt students to consider. For example, CyberCivics provides a “Time Tracker” template where students log every activity (including but not limited to technology use) from morning until night and note the time spent, in minutes, on each activity. Students then bring their trackers to class, total their time on different activities, and use the data to make observations about their “digital diets.” InCTRL has a “24/7” log for tracking total technology time each day for a week. White Ribbon Week uses a circle graph divided into 24 slices where students shade in the number of hours they spend on different activities and then discuss what it means to “balance” a day. Common Sense has a “Media Choices Inventory” (embedded in a 7th-grade lesson), which prompts students to reflect on their media use from the prior day: “What media did you use?” “When did you use it?” (e.g., morning), “How much time did you spend?” (in minutes), and “How did you feel?” MediaSmarts offers a “Media Diary” where students fill out a checklist each day for a week to indicate “What I did using screen media” by checking boxes that correspond to digital activities like entertainment, keeping in touch, seeing what people are doing, posting or browsing photos, online learning, and music. Students simultaneously keep a separate “Mood Diary” focused on tracking, for each day, how they “experienced my different relationships and connections today” and then “How I felt today” overall. Other self-reflection lessons do not include logging tools but take approaches like directing students to take stock of all current digital habits and how each habit makes them feel (Common Sense, “Digital Habits Check-up”), or completing a “Digital Stress Self-test” to notice problematic digital habits (Media Smarts, “Dealing with Digital Stress”).

The aforementioned lessons share an emphasis on promoting healthy digital media use by building students’ awareness of their own technology habits. Keeping a media-use diary is an established approach in traditional media literacy education (Hobbs, Reference Hobbs2010). As Hobbs describes, “record-keeping activities help people keep track of media choices and reflect on decisions about sharing and participation, deepening awareness of personal habits” (p. 23). In the context of digital media, negative outcomes from technology use are often mediated by negative experiences people have while using technology (e.g., social comparison, FOMO; Burnell et al., Reference Burnell, George, Vollet, Ehrenreich and Underwood2019). Noticing and disrupting negative digital experiences may therefore serve a protective function. Recognizing, for example, that browsing Instagram before bed is contributing to anxious thoughts or that TikTok is a source of unwanted distraction during homework time can set the stage for making different choices. In this vein, Carrier and colleagues (Reference Carrier, Rosen and Rokkum2018) argue for digital metacognition as a relevant digital-age coping practice. They argue that critical self-reflection facilitates digital metacognition, which involves thinking intentionally and strategically about one’s technology choices. Self-reflection tools that help students draw links between specific digital activities and corresponding emotional reactions ostensibly support digital metacognition. At the same time, research is clear that how young people use technology is more important than simply how much they use (Reeves et al., Reference Reeves, Robinson and Ram2020). Self-reflection lessons that place heavy emphasis on logging screen time without further differentiation (e.g., of how time is spent or what emotions it evokes) may therefore prove less effective.

These are, for the most part, hypotheses rather than conclusions. That said, one cluster randomized controlled trial of a school-based intervention in German schools showed promising results of a media intervention anchored in self-reflection that was designed to build metacognition related to online gaming activities (Walther et al., Reference Walther, Hanewinkel and Morgenstern2014). Future research should examine the specific curricular features that support effective digital self-reflection lessons: Does it make a difference if students reflect generally about digital habits versus if they track technology use? If tracking technology use is effective, what is the optimal duration for tracking (e.g., one day, one week) and what, specifically, should students be prompted to track (e.g., time spent, activities, emotional reactions)? How can curricula prompt both a light-bulb-type recognition of digital experiences and, crucially, support dispositional tendencies toward ongoing digital metacognition? Given that young people’s cognitive capacities for self-reflection develop over time, it may also be important to explore how different kinds of self-reflective activities align with students’ ages and developmental stages.

Behavioral Change for Healthy Digital Habits

Naturally, the end goal of much curriculum is behavioral change outside of the classroom: helping students establish and maintain healthy technology use in their real lives. Nearly all of the existing lessons we reviewed urge “balance” as a key aim. Some lessons utilize metaphors to concretize the finite nature of time and/or help students consider ways to balance technology with other activities or priorities. The Center for Humane Technology uses an “empty glass” metaphor to guide students’ thinking about the activities they use to fill their time. iKeepSafe uses the idea of a “rock garden of our life” to help students prioritize time spent on important “boulders” (career goals, friends) and “pebbles” (school work), and “grains of sand” (screen time). MediaSmarts uses the metaphor of a “media diet” with older students (this metaphor is also used by CyberWise); for younger students, the concept of balance is conveyed through an equally divided pie chart that has separate portions students fill out for active time, learning time, and screen time.

One way in which lessons try to help students achieve balance is through intention-setting activities. These involve making commitments that help bound screen time and facilitate other priorities and activities. Templates guide students in making “pledges” about their technology use (e.g., DQ Institute and iKeepSafe) or to work with their parents/guardians on “family media agreements” (e.g., Common Sense). Lessons also seek to support healthy habits in students’ lives outside of the classroom by teaching specific behavioral strategies. On-device strategies include, for example:

using apps to track and manage screen time;

adding browser extensions that support focused study time;

unfollowing or muting social media accounts that evoke negative reactions;

switching phone screens to grey scale;

turning off push notifications; and

trying to prioritize active rather than passive activities on social media.

Off-device strategies include practices like:

putting phones out of sight before bed;

using a “phone stack” when hanging out with friends to reduce digital distractions during face-to-face socializing;

scheduling screen time and screen-free time in advance;

keeping a personal inventory of favorite offline activities (e.g., basketball, coloring, yoga) to refer back to; and

identifying self-soothing and/or active nondigital activities that relieve boredom or sadness.

Another avenue toward behavioral change is scaffolding more deliberate personal challenges in which students actually try out strategies or plans that change their typical media habits. These challenges take the form of instructor-prompted digital media breaks (CyberWise, “Social Media Vacation”; MediaSmarts, “Disconnection Challenge”; Digital Future Initiative, “Digital Time Out”) and student-designed experiments to change a specific digital habit of their choice (Common Sense Education, “Digital Habits Check-Up”; White Ribbon Week, “Device-Free Zone”). Memorable heuristics like rhymes, acronyms, and thinking routines are used in some lessons to encourage retention of key principles. Examples include Common Sense’s “pause, breathe, finish up” saying to help younger students wrap up their technology use and Digital Future Initiative’s D framework “4 C’s” (Count to ten, Consider possible consequences, Careful with moods and emotions, Check for advice).

We still have much to learn about whether, how, and why these approaches actually enable healthy digital media behaviors. Technology pledges and agreements are one type of intervention that warrants focused study. On the one hand, these tools may facilitate proactive planning that supports digital metacognition and establishes valuable boundaries, in addition to catalyzing conversations between youth and their parents/caregivers. Research on rule-setting related to technology use is mixed, though, and generally suggests that compliance (or a lack thereof) is shaped by the content of the rules and young people’s relationships with the adults who are designing, implementing, and enforcing those rules (e.g., Hiniker et al., Reference Hiniker, Schoenebeck and Kientz2016; Kesten et al., Reference Kesten, Sebire, Turner, Stewart-Brown, Bentley and Jago2015). Technology limits handed down from adults can be ineffective or outright backfire (Samuel, Reference Samuel2015). Further, research on student pledges related to honor codes suggests that asking students to simply make a one-time pledge to follow a preconstructed set of principles is insufficient (LoSchiavo & Shatz, Reference LoSchiavo and Shatz2011). The idea that students will make commitments about their technology use and then simply follow through on those plans may also overlook the impacts of persuasive design features (Alter, Reference Alter2017), social pulls and pressures, and developmental changes as students get older. Likely, the value of pledges and media agreements depends on how they are developed and then used. Relevant, too, is the aforementioned experimental research, which demonstrated that education about persuasive tech design features – presented alongside messages about autonomy and social justice – can boost adolescents’ motivation to self-regulate social media use (Galla et al., Reference Galla, Choukas‐Bradley, Fiore and Esposito2021). Yet these experiments also underscore that motivational changes are no guarantees of lasting behavioral change (Galla et al., Reference Galla, Choukas‐Bradley, Fiore and Esposito2021).

Learning behavioral strategies may build digital agency and support self-regulation. Agency and efficacy – which both involve competence, confidence, and control – are inherently linked to psychological well-being (e.g., Bandura, Reference Bandura1989). Students have digital agency when they can control and manage their personal uses of technologies (Passey et al., Reference Passey, Shonfeld, Appleby, Judge, Saito and Smits2018). The strategies embedded in existing lessons arguably add “friction” to disrupt typical routines and unwanted, automatic behaviors – a crucial principle of habit change (Clear, Reference Clear2018). For example, strategies like using a phone stack create friction against the habit of instinctively checking messages during a dinner with friends; disabling push notifications reduces the otherwise ongoing diversion of attention that can derail focus during study time. However, it is not clear whether the strategies advocated in current lessons cover the most relevant approaches used by savvy youth. A key area for future research is identifying behavioral strategies that adolescents are already using and/or which resonate with their authentic device struggles and self-identified values and goals. Relatedly, what paves the way from learning about a strategy in class to trying it outside of the classroom, and to deploying it on a routine basis?

Digital Citizenship Education: State of the Field

Above, we describe a suite of potentially promising pedagogies keyed to three crucial learning goals for supporting healthy digital habits. In Figure 15.1, we distill these three distinct learning goals of existing digital habits lessons and propose a cyclical relationship among them. Although we developed this model based on our review of lessons that target digital habits and media balance, it holds broader relevance for other aspects of technology use – such as online sharing and digital footprints. This model may offer a guide for assessing digital citizenship lesson content and pedagogies.

Figure 15.1 Educating for healthy digital media use: three core learning goals

These three focal aims – critical awareness, self-reflection, and behavioral change – likely have relevance beyond school settings, too, and particularly for mental health professionals who work directly with youth. Consider, for example, a teen whose struggle with depression appears to be exacerbated by social comparison on social media (Nesi & Prinstein, Reference Nesi and Prinstein2015). Building critical awareness could begin with discussion of the ways social media feeds can function as highlight reels that invite comparison (Weinstein, Reference Weinstein2017). Self-reflection might then involve engaging the teen in a process of self-identifying whether and when this pattern holds in their personal media use: Are there specific accounts that lead them to compare themself to others in ways that erode their mood or well-being? This self-reflection step could include building digital metacognition so that they begin to self-monitor and recognize when comparative thinking comes up in their everyday media use. Behavioral change could be supported through active strategies, like curating their social media feed(s) by unfollowing accounts that spark toxic comparison and adding accounts that encourage recovery and spark inspiration.

Returning to the context of school-based efforts, our review confirms overall that there are a number of available resources designed for digital citizenship and the intended promotion of healthy digital habits. Many of these resources are free, well-developed materials that are ready for immediate use and accompanied by detailed guidance for facilitators. Educators who are interested in promoting healthy digital media use will likely have little trouble finding relevant supports. What is less clear at this point is whether available resources actually achieve their intended aims and, more generally, which pedagogical approaches are effective and for whom.

We caution, too, that research about digital citizenship topics themselves (e.g., young people’s experiences with digital drama, sexting pressures, news and civic life, and creating healthy digital habits) is rapidly evolving and extremely relevant to the content of classroom lessons. Notably, in some cases, research consensus is hard won. Ongoing debates about the interpretations of evidence regarding impacts of technology use on mental health are a relevant example. It is understandable, then, that creators of school programs might struggle to distill the latest empirical research into clear, age-appropriate instructional content and classroom materials. In reviewing the digital habits lessons, we saw at least three instances of decisive curricular messages that are arguably misaligned with current research: (1) using the language of “addiction” to characterize everyday media habits; (2) describing a causal relationship between media activities and mental health issues (e.g., depression, anxiety, suicide risk); and (3) emphasizing total screen time without any attention to the types of digital activities that comprise that time. In addition to including potentially problematic messages, we noted examples of simplistic and likely ineffective instructional approaches (e.g., just telling all students “Don’t compare yourself to others on social media”) (see Weinstein, Reference Weinstein2017 for context on why this approach may fall short). We also observed in some lessons a clear implication that offline activities are inherently more worthwhile than any online activities.

Researchers must also attend to different methods of implementation for school-based interventions. As we have touched on above, research should go beyond analysis of curricular content to consider details like where (e.g., advisory, health class, social studies, whole school assembly), how often (e.g., “one and done” versus multiple lessons across a semester or year), and who facilitates (e.g., classroom teacher, guidance counselor, expert guest speaker, peer mentor). A further question about interventions for healthy digital media use is by whom and for whom. Who decides what constitutes healthy versus unhealthy use, particularly given that youth use technologies in ways that reflect dramatically different offline circumstances and access to resources (Ito et al., Reference Ito, Odgers and Schueller2020; Odgers, Reference Odgers2018)? Who actually receives digital citizenship interventions and in which ways do such interventions “meet them where there are” versus miss the mark?

There remain persistent and pernicious inequities across US education (e.g., Jencks & Phillips, Reference Jencks and Phillips2011; Reardon, Reference Reardon, Duncan and Murnane2011). The recent example of remote learning during the COVID-19 pandemic provided yet another illustration of the ways in which young people differentially experience learning on a day-to-day basis in ways that set them up for stark differences in learning, health, and well-being outcomes (MacGillis, Reference MacGillis2020). Unsurprisingly, educational inequities play out in the context of technology-related education in ways that disproportionately impact black, Latino, and low-income youth (Watkins & Cho, Reference Watkins and Cho2018). A puzzle relates to who is responsible for attending to equity concerns when it comes to teaching digital topics. Should consideration of vulnerable students, and specific vulnerabilities, be “baked into” digital citizenship curricula and associated teacher supports? Or should programs leave it to teachers to make relevant adaptations for their students – whether they be students who have constrained resource access those who face learning challenges, those who have known mental health challenges, or any other number of relevant vulnerabilities? These questions are key for research, relevant to policy, and consequential from an ethical standpoint.

Other School-Based Approaches for Supporting Healthy Digital Media Use

Notably, digital citizenship curricula are but one approach to supporting healthy digital media use. The literature also suggests considerable advantages to integrating internet safety into already well-established and evidence-based programs that address related off-line harms (see Finkelhor et al., Reference Finkelhor, Walsh, Jones, Mitchell and Collier2020 for discussion). This integrative approach recognizes the considerable overlap between offline and online behaviors and corresponding intervention strategies. For example, as Finkelhor et al. (Reference Finkelhor, Walsh, Jones, Mitchell and Collier2020) describe, cyberbullying co-occurs with offline victimization and well-established prevention strategies for bullying hold relevance for cyberbullying (e.g., norm-setting about acceptable versus hurtful behaviors, teaching de-escalation strategies, discussing bystander support). Educational interventions that integrate cyberbullying with offline bullying appear effective based on meta-analytic review (Gaffney et al., Reference Gaffney, Farrington, Espelage and Ttofi2019). Finkelhor and colleagues argue that internet addiction/overuse is another topic best addressed through integration with existing interventions, specifically those that promote mental and physical health for high-risk youth, for example, by developing self-control, time management skills, and parental mediation.

Schools can also model or promote digital citizenship and healthy digital media use beyond the classroom lesson format. Additional venues for extra-curricular, school-based interventions – all of which are potentially relevant to digital citizenship – include whole school assemblies, peer-to-peer mentoring programs, and family engagement events. Acceptable use policies also set overarching guidelines and expectations for at-school technology use and/or the use of school-provided devices. These policies may bear resemblance to the aforementioned use-related “pledges” and represent another school channel for communicating messages and values about technology use.

Conclusion

Today’s digital technologies are designed with compelling features that contribute to their allure. These apps and devices are created to capture and hold people’s attention: designed and iterated to be “irresistible” (Alter, Reference Alter2017). Youth readily use these tools, though technologies are rarely created with young people’s healthy development front of mind. For adolescents, normative developmental drives and vulnerabilities contribute to heightened interest in the affordances digital media provide, from peer feedback to immediate rewards in gaming and on social media. While debate continues about the specific nature and mechanisms by which screen activities impact mental health, there is little question that digital media use should be a standard component of discussions about youth well-being.

As prior chapters in this handbook address, young people with particular mental health challenges may use digital media in ways that mirror or amplify risks. Clinical intervention represents an important avenue for providing these youth with targeted support. Yet questions about promoting healthy digital media use are widely relevant, and arguably merit attention with any and every young person who uses digital tools. Schools are a natural context for interventions particularly as they increasingly provide students with access to devices and encourage or require digital media use for learning. Our review documents a range of digital citizenship curricula and related resources to guide school-based intervention. These resources vary in their focal topics and in their approaches to those topics, as well as in terms of their formats, target grade levels, fee structures, and messaging. Across lessons that specifically target healthy digital habits, we observed three common learning goals: (1) building critical awareness so that students recognize and understand psychological dynamics and digital affordances that shape technology use; (2) scaffolding self-reflection that prompts students to take stock of their current digital media use and build digital metacognition; and (3) supporting behavioral change through strategies that promote digital agency and well-being. While programs often cover one or two of these learning goals, there is potential power in a three-pronged approach. Overall, relevant research suggests these aims and their corresponding approaches are good bets for supporting healthy digital media use. But, at present, we do not have a sufficient evidence base to guide decision-making about school-based interventions for promoting healthy digital media use. What works, for whom, and under what circumstances? Which topics, messages, and approaches align with current research on digital life and adolescent mental health/well-being? To what extent and how should school-based digital citizenship interventions be designed with an explicit equity lens?

All told, school-based interventions offer tangible ways to reach and support young people. Moving toward a set of well-developed and evidence-based curricular resources for digital media use will provide vital direction for the field.

The majority of mental health problems first emerge during the adolescent years (Kessler et al., Reference Kessler, Berglund, Demler, Jin, Merikangas and Walters2005). Thus, adolescence is a critical developmental window for both mental health prevention and intervention. Despite improvements in our understanding and ability to detect and treat youth mental health problems, there remains a persistent need for mental health services among youth, with the majority of youth untreated (Cummings et al., Reference Cummings, Wen and Druss2013; Merikangas et al., Reference Merikangas, He and Burstein2011). Among youth who do get treatment, there is often a long gap between the onset of symptoms and when youth first receive treatment (de Girolamo et al., Reference de Girolamo, Dagani, Purcell, Cocchi and McGorry2012), as well as low treatment attendance and completion in this population. As rates of mental health problems such as depression and suicidality continue to rise during adolescence (Centers for Disease Control, 2018), the gap between those who need and receive mental health services will only continue to grow.

In this chapter, we review the potential for technology to advance our understanding and treatment of mental health problems among adolescents through digital mental health interventions (DMHIs). We first discuss existing barriers to mental health care among adolescents, followed by a discussion of how DMHIs can address these barriers to improve access to and quality of adolescent mental health services. We then review existing research on DMHIs and the digital frameworks that are used to collect and deliver psychoeducation, assessment, and interventions across different hardware (e.g., smartphones, computers) and modalities (e.g., online, text, apps). Finally, we conclude with a discussion of the current limitations of DMHIs and key directions for the field to improve adolescent mental health care using DMHIs.

Barriers to Existing Mental Health Services

Significant, and often systemic, barriers interfere with access and delivery of mental health services for adolescents, including barriers related to cost, geographic proximity, and time, among others. These barriers often result in long waitlists and travel times, as well as a shortage of professionals providing evidence-based care (Andrilla et al., Reference Andrilla, Patterson, Garberson, Coulthard and Larson2018), particularly those who are trained to work with youth (American Psychological Association, 2016). Access to treatment is especially challenging for youth in rural regions (Andrilla et al., Reference Andrilla, Patterson, Garberson, Coulthard and Larson2018) and for adolescents who are racial, ethnic, sexual, and/or gender minorities. These youth often face additional barriers to receive culturally sensitive care (Alegria et al., Reference Alegria, Vallas and Pumariega2010). Inadequate education about mental illness, distrust of medical providers, and stigma about help-seeking behaviors (i.e., internalizing stigma) and mental health care (i.e., treatment stigma) also prevent adolescents from seeking help (Clement et al., Reference Clement, Schauman and Graham2015; Gulliver et al., Reference Gulliver, Griffiths and Christensen2010). Teens also often lack awareness and understanding of their symptoms as clinically significant, are uneducated about their treatment options, or are hesitant to share their symptoms with parents or other adults (Gulliver et al., Reference Gulliver, Griffiths and Christensen2010). Even when youth do access mental health care, treatment completion and compliance are often low due to these persistent barriers (e.g., cost, time, transportation, stigma). Thus, there is a critical need for services that are scalable, accessible, and developmentally appropriate for the prevention and intervention of adolescent mental health problems.

Potential Benefits of Digital Mental Health Interventions for Adolescents

Advancing technologies offer novel opportunities to improve the detection, prevention, and treatment of mental health problems. DMHIs have the potential to revolutionize mental health care by providing effective, accessible, scalable, and low-cost interventions. While adolescents are at heightened risk for mental health problems, they also may be uniquely positioned to benefit from DMHIs and novel digital tools (Wong et al., Reference Wong, Madanay and Ozer2020).

DMHIs can overcome many of the aforementioned systemic and individual barriers for youth (e.g., availability, cost, transportation, stigma). There are several factors that suggest DMHIs may be promising for adolescent mental health care. First, certain technologies to deliver DMHIs are already widely in use. For example, smartphones have become nearly ubiquitous among youth, with over 95% of teens owning these regardless of gender, race/ethnicity, or sexual identity (Anderson & Jiang, Reference Anderson and Jiang2018). Second, adolescents are early adopters of many digital technologies. They report high levels of comfort with and preference for online communication, particularly when discussing mental health (Bradford & Rickwood, Reference Bradford and Rickwood2015). Thus, DMHIs also promote help-seeking behaviors and can serve as a “gateway” to initiating mental health care (Kauer et al., Reference Kauer, Mangan and Sanci2014). Third, adolescents also commonly use the Internet for mental health information (Leanza & Alani, Reference Leanza, Alani, Moreno and Hoopes2020; Park & Kwon, Reference Park and Kwon2018), which is especially the case for adolescents who identify as racial/ethnic minorities or have parents that are less health literate (Park & Kwon, Reference Park and Kwon2018). Finally, as the first point of entry for many adolescents, DMHIs can facilitate treatment by reducing uncertainty about interactions with providers and ambiguity about treatment options (Boydell et al., Reference Boydell, Hodgins, Pignatiello, Teshima, Edwards and Willis2014). Rather than being a passive participant, teens can gain a newfound understanding and agency over their mental health, which may promote treatment seeking and engagement.

Further, while stigma toward help-seeking and mental health care is prominent across age groups (Sharac et al., Reference Sharac, McCrone, Clement and Thornicroft2010), adolescents identify stigma as one of the greatest barriers to mental health care (Gulliver et al., Reference Gulliver, Griffiths and Christensen2010). DMHIs can be anonymous, private, and accessible to teens at any time of the day and in any location, thereby allowing teens to access and receive mental health care in the way that is most comfortable for them (Toscos et al., Reference Toscos, Coupe and Flanagan2019). In this sense, DMHIs can reach diverse groups of adolescents efficiently by connecting with teens where they are (online) and in the digital spaces where they feel most comfortable. DMHIs have the potential to not only reduce the gap in mental health services and delivery, but also reduce mental health disparities that exist across youth who are marginalized or undeserved (Schueller et al., Reference Chu, Wadham and Jiang2019). DMHIs can provide readily available, reliable, and accurate mental health information to adolescents, particularly youth who are traditionally underserved in mental health care. DMHIs may also be more readily adaptable or translated into other languages, which may help with the limited availability of multilingual mental health professionals. However, inequities in access to technology may actually create a digital divide in who has access to DMHIs (Odgers & Jensen, Reference Odgers and Jensen2020). By collecting and delivering content in real time and in real-world contexts, DMHIs have the potential to inform and deliver timely, flexible, and personalized mental health care, thereby improving detection and treatment of mental health problems across risk stages and demographics (Price et al., Reference Price, Yuen and Goetter2014).

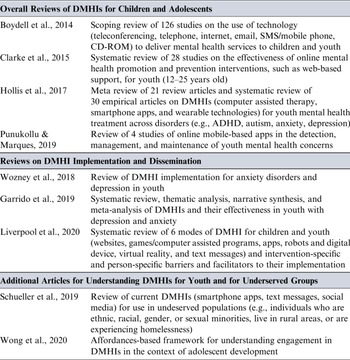

Modes of Delivery for Digital Health Interventions

As technology evolves, an abundance of novel digital platforms and tools have been developed to improve mental health among youth and adults. DMHIs provide online services for interventions through various hardware (e.g., computer, phone, tablet, wearable) and modalities. These modalities include online/web-based interventions, video conferencing, text messaging, smartphone applications (“apps”), social media sites, game-based approaches (e.g., “serious games”) (Lister et al., Reference Li, Theng and Foo2014), virtual reality, as well as emerging technologies like passive sensing (e.g., wearables, digital phenotyping) and artificial intelligence (e.g., chatbots). Yet, technology has far outpaced research on DMHIs. Most work examining DMHIs is heavily skewed toward modalities that have existed longer (e.g., telehealth, online/web-based interventions). Newer modalities of delivering mental health services, such as mobile health (e.g., text messaging, apps), wearables, or games, are still in the earlier phases of testing for treatment effectiveness with youth. Nevertheless, given their promise for reducing the burden of mental health problems in adolescents, the field is rapidly expanding to empirically evaluate DMHIs for adolescent mental health problems. Below, we briefly discuss the potential benefits and effectiveness of a range of specific DMHI modes of delivery. Table 16.1 provides a review of suggested readings about DMHIs’ effectiveness and implementation. Later in this chapter, we will discuss potential challenges of these technologies for mental health interventions.

Table 16.1 Suggested readings for understanding DMHIs’ effectiveness, implementation, and future directions

| Overall Reviews of DMHIs for Children and Adolescents | |

|---|---|

| Boydell et al., Reference Boydell, Hodgins, Pignatiello, Teshima, Edwards and Willis2014 | Scoping review of 126 studies on the use of technology (teleconferencing, telephone, internet, email, SMS/mobile phone, CD-ROM) to deliver mental health services to children and youth |

| Clarke et al., Reference Clarke, Kuosmanen and Barry2015 | Systematic review of 28 studies on the effectiveness of online mental health promotion and prevention interventions, such as web-based support, for youth (12–25 years old) |

| Hollis et al., Reference Hollis, Falconer and Martin2017 | Meta review of 21 review articles and systematic review of 30 empirical articles on DMHIs (computer assisted therapy, smartphone apps, and wearable technologies) for youth mental health treatment across disorders (e.g., ADHD, autism, anxiety, depression) |

| Punukollu & Marques, Reference Punukollu and Marques2019 | Review of 4 studies of online mobile-based apps in the detection, management, and maintenance of youth mental health concerns |

| Reviews on DMHI Implementation and Dissemination | |

|---|---|

| Wozney et al., Reference Wozney, McGrath and Gehring2018 | Review of DMHI implementation for anxiety disorders and depression in youth |

| Garrido et al., Reference Garrido, Millington and Cheers2019 | Systematic review, thematic analysis, narrative synthesis, and meta-analysis of DMHIs and their effectiveness in youth with depression and anxiety |

| Liverpool et al., Reference Liverpool, Mota and Sales2020 | Systematic review of 6 modes of DMHI for children and youth (websites, games/computer assisted programs, apps, robots and digital device, virtual reality, and text messages) and intervention-specific and person-specific barriers and facilitators to their implementation |

| Additional Articles for Understanding DMHIs for Youth and for Underserved Groups | |

|---|---|

| Schueller et al., Reference Chu, Wadham and Jiang2019 | Review of current DMHIs (smartphone apps, text messages, social media) for use in undeserved populations (e.g., individuals who are ethnic, racial, gender, or sexual minorities, live in rural areas, or are experiencing homelessness) |

| Wong et al., Reference Wong, Madanay and Ozer2020 | Affordances-based framework for understanding engagement in DMHIs in the context of adolescent development |

Note: Full references are available in the References section.

Videoconferencing

Telehealth services (e.g., telephone and videoconferencing) most closely mirror traditional face-to-face assessment and treatment delivery, and also offer new opportunities. Videoconferencing provides synchronous communication between patients and providers, with the increased convenience for patients of eliminating travel. Being in one’s natural environment has the potential to improve ecological validity of both assessment and treatment for youth with certain mental health problems (e.g., depression, psychosis, anxiety) compared to traditional treatment in an office or hospital setting. Specifically, videoconferencing may allow the clinician to observe the home environment to better assess a teen’s home or provide opportunities to participate in more naturalistic exposures. Therapy conducted using videoconferencing has received empirical support to effectively treat a range of youth mental health problems (Myers et al., Reference Myers, Valentine and Melzer2007, Reference Myers, Valentine and Melzer2008; Nelson et al., Reference Nelson, Cain and Sharp2017). Videoconferencing is now relatively common and accepted in mental health care among professionals, youth, and their caregivers (Boydell et al., Reference Boydell, Hodgins, Pignatiello, Teshima, Edwards and Willis2014). Following the physical distancing practices of the COVID-19 pandemic (Gruber et al., Reference Gruber, Prinstein and Clark2021), videoconferencing will likely continue to increase in its use and acceptability as a means of providing mental health care to youth. Despite its more common use in mental health care compared to other DMHIs, empirical research is still underway to provide guidance for the use of videoconferencing (Nelson et al., Reference Nelson, Cain and Sharp2017), including how to ethically navigate patient boundaries in their homes, which will be critical for delivering care using this modality.

Online/Web-Based Interventions

Online or web-based platforms can provide a myriad of services. This includes: access to comprehensive mental health information (e.g., blogs, websites); scalable, affordable, and effective interventions to youth and their families for mental health problems; and translation of existing evidence-based treatments into computerized or online lessons, modules, or sessions accompanied by homework or tasks, among others. Systematic and meta-analytic reviews of randomized control trials (RCTs) support the effectiveness of online/web-based services for treating adolescent mental health problems (Clarke et al., Reference Clarke, Kuosmanen and Barry2015; Hollis et al., Reference Hollis, Falconer and Martin2017). Most studies have been conducted with youth with subclinical or clinical levels of depression and anxiety (Grist et al., Reference Grist, Croker, Denne and Stallard2019; Khanna et al., Reference Khanna, Carper, Harris and Kendall2017). To date, online interventions for these clinical problems have garnered the most support. Most online or web-based interventions are based on cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) (Ebert et al., Reference Ebert, Zarski and Christensen2015). The majority of computerized and internet-based CBT programs were found to be of moderate to high quality (Clarke et al., Reference Clarke, Kuosmanen and Barry2015; Wozney et al., Reference Wozney, McGrath and Gehring2018). These programs included components of self-monitoring, interactive content (e.g., videos, characters storytelling, games), and both online and offline support. However, online programs now include other treatment modalities and approaches for targeting youth mental health problems (Garrido et al., Reference Garrido, Millington and Cheers2019), such as positive psychology, mindfulness (Ritvo et al., Reference Ritvo, Daskalakis and Tomlinson2019), and problem-solving (Hoek et al., Reference Hoek, Schuurmans, Koot and Cuijpers2012).

Importantly, there is a need to better understand the level of human interaction (if any) needed for online or web-based interventions to be effective with youth mental health treatment, especially to counter low rates of engagement and adherence. Most online or web-based interventions are therapist-assisted, including a virtual or online therapist or to supplement in-person and face-to-face clinician visits. Meta-analytic reviews suggest online interventions that included therapists or clinicians performed better in reducing depression and anxiety symptoms than interventions that were self-guided (Clarke et al., Reference Clarke, Kuosmanen and Barry2015; Hollis et al., Reference Hollis, Falconer and Martin2017). Indeed, some research suggests that self-guided online or web-based interventions were not effective for youth depression (Garrido et al., Reference Garrido, Millington and Cheers2019). Alternatively, some studies indicate that minimal therapist involvement was better for youth anxiety than significant or more extensive therapist involvement (Podina et al., Reference Podina, Mogoase, David, Szentagotai and Dobrean2016).

Some of the largest barriers for self-guided online treatments for adolescents are low rates of treatment completion and adherence (Clarke et al., Reference Clarke, Kuosmanen and Barry2015; Garrido et al., Reference Garrido, Millington and Cheers2019). To address these concerns, low-intensity web-based interventions have been developed to deliver skill-based interventions in single sessions (Schleider & Weisz, Reference Schleider and Weisz2018). Self-administered online single-session interventions have demonstrated effectiveness in reducing adolescent depressive symptoms, as well as other core characteristics of depression (e.g., low perceived agency, self-worth, and hopelessness; Schleider & Weisz, Reference Schleider and Weisz2018; Schleider, Dobias, Sung, & Mullarkey, Reference Schleider, Dobias, Sung and Mullarkey2020). One recent trial found that online single-session interventions demonstrate effectiveness in natural settings and also reach a large number of adolescents with one or more marginalized identities (Schleider, Dobias, Sung, Mumper, & Mullarkey, Reference Schleider, Dobias, Sung and Mullarkey2020). Thus, online single-session interventions may offer brief, low-intensity, accessible, and scalable mental health interventions for youth who may otherwise not engage in care, possibly serving as tools for universal or indicated prevention or during transitional periods of more intensive care. More research and diversification of these online brief interventions (e.g., length, type) is needed to evaluate the setting and context in which they are most effective (Schleider, Dobias, Sung, Mumper, & Mullarkey, Reference Schleider, Dobias, Sung and Mullarkey2020). Further, a recent RCT tested the effectiveness of a web-based decision aid to support young people in help-seeking for their self-harm (Rowe et al., Reference Rowe, Patel and French2018). Youth generally reported the online decision aid to be acceptable, easy to use, and informative for seeking help, which suggests another way in which online or web-based interventions can promote adolescent mental health.

Text Messaging

Text messaging can also be an affordable and effective way of providing interventions, monitoring symptoms, or prompting adolescents to engage in behaviors to promote mental health, such as coping skills during crisis. This type of platform can prompt adolescents to employ skills, as well as provide automated reminders for appointments and medication to improve treatment attendance (Branson et al., Reference Branson, Clemmey and Mukherjee2013). Texts can be personalized and tailored to the adolescent based on their needs and preferences by altering the message frequency, content, and customized interactions. Text-based services may be an especially accessible DMHI. Nearly all youth have mobile phones and smartphones and text messaging does not require internet for delivery. Further, text messaging interventions are not at risk for deletion, which is common for smartphone apps (Baumel et al., Reference Baumel, Muench, Edan and Kane2019), as text capabilities are embedded in phones. Text messaging interventions also may have lower upfront costs for development compared to apps that need to be adapted and delivered for both iOS and Android platforms. Importantly, there is some support for the effectiveness of text interventions for treating youth health problems (Loescher et al., Reference Loescher, Rains, Kramer, Akers and Moussa2018), including substance use and depression (Mason et al., Reference Mason, Ola, Zaharakis and Zhang2015; Whitton et al., Reference Whitton, Proudfoot and Clarke2015). Further, a recent text messaging intervention also improved the mental health literacy of parents of adolescents (Chu et al., Reference Chu, Wadham and Jiang2019), which may subsequently improve mental health care for teens by reducing one potential barrier to treatment.

Smartphone Apps

The widespread ownership of mobile phones, particularly smartphones, provides unparalleled and unobtrusive access to adolescents in real time and in the “real world” to deliver scalable and low-cost mental health interventions. Current mental health apps can serve multiple purposes, including for psychoeducation, monitoring symptoms or behaviors, providing “just in time” or ecological momentary interventions, and as adjunctive or stand-alone treatments. There are many potential benefits to using apps to engage youth in mental health services, including heightened sense of privacy, accessibility, convenience, and integration in daily life. Importantly, apps can be more personalized and tailored to the individual, and can provide more developmentally appropriate and interactive material that engages adolescents (Bakker et al., Reference Bakker, Kazantzis, Rickwood and Rickard2016). For some youth, the very act of mental health monitoring may be beneficial in improving symptoms (Kauer et al., Reference Kauer, Reid and Crooke2012), which can be delivered in a user-friendly manner and can be used as a preventive measure or adjunct to treatment. Monitoring apps that serve as an adjunct to treatment may increase engagement among youth, allowing adolescents to have an increased awareness and sense of agency over their own behavior and mental health symptoms. However, most monitoring apps available for download have received limited empirical support. In general, relatively few apps have been empirically tested to determine their effectiveness in treating youth mental health problems (Melbye et al., Reference Melbye, Kessing, Bardram and Faurholt-Jepsen2020; Punukollu & Marques, Reference Punukollu and Marques2019).

Although research is limited, apps designed to supplement other mental health treatment and aid care between sessions have demonstrated effectiveness, particularly for youth anxiety (Carper, Reference Carper2017; Pramana et al., Reference Pramana, Parmanto, Kendall and Silk2014; Silk et al., Reference Silk, Pramana and Sequeira2020). These apps enhance treatment exposures and skills-based practice, homework compliance, and symptom tracking between sessions. Apps also have the potential to provide adolescents with “just in time” adaptive interventions that are low-intensity and high-impact and when they most need it most, such as times of crisis. Indeed, specific suicide prevention apps have been developed (Martinengo et al., Reference Martinengo, Van Galen, Lum, Kowalski, Subramaniam and Car2019), with preliminary evidence of positive treatment effects (Arshad et al., Reference Arshad, Farhat Ul, Gauntlett, Husain, Chaudhry and Taylor2020). While not encouraged to be stand-alone treatments, digital safety planning and tools (Kennard et al., Reference Kennard, Biernesser and Wolfe2015, Reference Kennard, Goldstein and Foxwell2018) may help adolescents at risk for suicide while youth are in crisis or during high-risk periods by addressing the gap between hospital discharge and outpatient treatment.

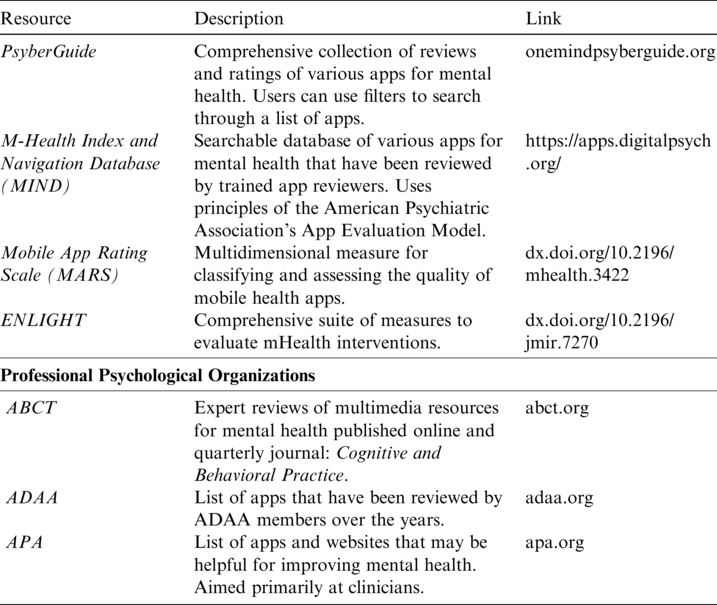

Most evidence-based apps developed by researchers are not yet commercially available (Punukollu & Marques, Reference Punukollu and Marques2019). In contrast, there are tens of thousands of commercially available apps for mental health, highlighting the large divide between apps developed for commercial use compared to those developed by researchers. Few of these available apps have been tested for effectiveness and most popular apps do not include therapeutic elements (Wasil et al., Reference Wasil, Venturo-Conerly, Shingleton and Weisz2019), though empirical evaluation is currently underway for some commercial apps (Bry et al., Reference Bry, Chou, Miguel and Comer2018). There is also very little regulatory oversight of apps and limited available high-quality information on the effectiveness of commercially available apps (Boudreaux et al., Reference Boudreaux, Waring, Hayes, Sadasivam, Mullen and Pagoto2014). This can leave adolescents vulnerable to mental health misinformation or using DMHIs that offer little therapeutic benefits (and some that could be harmful). Given that adolescents report difficulty distinguishing accurate from inaccurate information sources (Park & Kwon, Reference Park and Kwon2018), user guidance is needed to inform teens, parents, and providers (Palmer & Burrows, Reference Palmer and Burrows2021). There are several resources available that provide quantitative feedback, rubrics, and recommendations about mobile apps (Table 16.2). However, teens would likely benefit from a readily available tool, available in app stores, to provide information to them on which apps are research-based (Lagan et al., Reference Lagan, Aquino, Emerson, Fortuna, Walker and Torous2020) in a developmentally appropriate manner.

Table 16.2 Resources for evaluating mental health apps

| Resource | Description | Link |

|---|---|---|

| PsyberGuide | Comprehensive collection of reviews and ratings of various apps for mental health. Users can use filters to search through a list of apps. | onemindpsyberguide.org |

| M-Health Index and Navigation Database (MIND) | Searchable database of various apps for mental health that have been reviewed by trained app reviewers. Uses principles of the American Psychiatric Association’s App Evaluation Model. | https://apps.digitalpsych.org/ |

| Mobile App Rating Scale (MARS) | Multidimensional measure for classifying and assessing the quality of mobile health apps. | dx.doi.org/10.2196/mhealth.3422 |

| ENLIGHT | Comprehensive suite of measures to evaluate mHealth interventions. | dx.doi.org/10.2196/jmir.7270 |

| Professional Psychological Organizations | ||

|---|---|---|

| ABCT | Expert reviews of multimedia resources for mental health published online and quarterly journal: Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. | abct.org |

| ADAA | List of apps that have been reviewed by ADAA members over the years. | adaa.org |

| APA | List of apps and websites that may be helpful for improving mental health. Aimed primarily at clinicians. | apa.org |

Game-Based Interventions