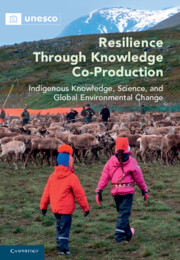

Resilience through Knowledge Co-Production

Resilience through Knowledge Co-Production Book contents

- Resilience through Knowledge Co-production

- Resilience through Knowledge Co-production

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Contributors

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Part I From Practice to Principles

- 2 The Progression from Collaboration to Co-production: Case Studies from Alaska

- 3 Learning about Sea Ice from the Kifikmiut: A Decade of Ice Seasons at Wales, Alaska, 2006-2016

- 4 Shaping the Long View: Iñupiat Experts and Scientists Share Ocean Knowledge on Alaska’s North Slope

- 5 Indigenous Ice Dictionaries: Sharing Knowledge for a Changing World

- 6 Mapping Land Use with Sámi Reindeer Herders: Co-production in an Era of Climate Change

- 7 Sámi Herders’ Knowledge and Forestry: Ecological Restoration of Reindeer Lichen Pastures in Northern Sweden

- Part II Indigenous Perspectives on Environmental Change

- Part III Global Change and Indigenous Responses

- Epilogue

- Index

- References

5 - Indigenous Ice Dictionaries: Sharing Knowledge for a Changing World

from Part I - From Practice to Principles

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 02 June 2022

- Resilience through Knowledge Co-production

- Resilience through Knowledge Co-production

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Contributors

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Part I From Practice to Principles

- 2 The Progression from Collaboration to Co-production: Case Studies from Alaska

- 3 Learning about Sea Ice from the Kifikmiut: A Decade of Ice Seasons at Wales, Alaska, 2006-2016

- 4 Shaping the Long View: Iñupiat Experts and Scientists Share Ocean Knowledge on Alaska’s North Slope

- 5 Indigenous Ice Dictionaries: Sharing Knowledge for a Changing World

- 6 Mapping Land Use with Sámi Reindeer Herders: Co-production in an Era of Climate Change

- 7 Sámi Herders’ Knowledge and Forestry: Ecological Restoration of Reindeer Lichen Pastures in Northern Sweden

- Part II Indigenous Perspectives on Environmental Change

- Part III Global Change and Indigenous Responses

- Epilogue

- Index

- References

Summary

At a meeting in Alaska in 2000, when several indigenous speakers shared stories about the rapidly shifting climate, sea ice, and weather in their home areas. I was amazed by how thoroughly they analysed signals of change and how nuanced their observations were, compared to the crude models of prehistoric climate change available in the literature. For many people living in the more temperate mid-latitude areas, ‘climate change’ is about heat and warming. Not so in the Arctic, where the best summary of climate change is that “it’s not cold enough” (Krupnik et al. 2010c). Indigenous people in the North, particularly those living on the seacoast, depend on long cold winter to build solid offshore ice. They monitor the ice for six to ten months every year; they travel on ice, and hunt from it to catch the animals that sustain their life. The Eskimo explanation “it’s not cold enough” has perfect sense from the principles of sea ice geophysics. It requires long cold days to build solid ice. If the ice is weak and broken, comes late or leaves early, more heat is absorbed into the ocean producing thinner and weaker ice next winter. This is a synopsis of what scientists call ‘Arctic amplification’. Over the past 40 years of satellite observations, Arctic sea ice has declined dramatically – in its seasonal extent, overall volume, age, and duration. In the northern Bering Sea, sea ice distribution in winter has changed, in professional terms, from a predictable system of icescapes to a mixing bowl of drifting floes. Hunters in many communities report that they have not seen thick bluish multi-year ice of their youth in years. Arctic people have noticed this transformation very early and they have spoken about it loud and clear since the late 1990s. Yet they monitor the ice from their particular vision of users, not as scientists. This paper introduces the study of indigenous sea ice nomenclatures as a path to document, sustain, and ‘co-produce’ local knowledge about ice and Arctic change.

Keywords

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Resilience through Knowledge Co-ProductionIndigenous Knowledge, Science, and Global Environmental Change, pp. 93 - 116Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2022