1 Introduction

This book defines “positive cyber peace” as a digital ecosystem that rests on four pillars:

(1) respecting human rights and freedoms, (2) spreading Internet access along with cybersecurity best practices, (3) strengthening governance mechanisms by fostering multistakeholder collaboration, and (4) promoting stability and relatedly sustainable development.

These pillars merit broad support for their emphasis on justice, good governance, and diffusion of technology to bridge the so-called “digital divide.” They were developed through a global vetting process over time and in different fora, and they represent views of technologists, civil society thought leaders, and representatives of intergovernmental organizations (see Permanent Monitoring Panel on Information Security of the World Federation of Scientists, 2009; Shackelford, Reference Shackelford2014). Nevertheless, the conceptualization of cyber peace and its pillars deserves further probing. Is cyber peace really a kind of peace? International relations and global studies theories include a substantial body of literature on peace, a condition and/or a relation that is both more capacious than the pillars and, perhaps, in some ways inconsistent with them. In addition, the pillars seem to be different kinds of things. The first refers to abstractions that are instantiated in law and take form through the practices of governments. The second is a diffusion of a technology along with technical standards. The third is a preference for a certain form of governance, and the fourth once again brings up a technical issue, but then pivots to sustainability. If the pillars are supporting an edifice, they are doing so unevenly.Footnote 1 In this chapter, I probe the ontological basis of the concept of cyber peace and uncover tensions in the meanings embedded in it.

The task begins with ontological questions about what kind of thing cyber peace is. This section draws on the definitions cyber peace advocates use to taxonomize the stated or implied assumptions about cyber peace as a condition or as a set of practices. As a condition, cyber peace is sometimes defined as a kind of peace, and at other times as something within cyberspace. Distinct modes of ontologizing cyber peace as a set of practices include cyber peace as cyber peacemaking, as maintaining the stability of information technology, and/or as cyber defense actions. The second section looks to international relations and cognate field scholarship for insight into further honing the conceptualization of cyber peace. The topics in this section include unpacking cyber as a modifier of peace, unpacking the concept of peace itself, exploring the boundaries of cyber peace by looking at how it is different from similar social things, and analyzing the implications of metaphors associated with cyber peace. The chapter concludes with a brief comment on the intent of the critique.

2 Contending Definitions

The ontological question is what kind of thing is cyber peace or would it be if it were to exist?Footnote 2 Unless practitioners and scholars can come to some kind of consensus around the ontological nature of cyber peace the project risks incoherence. As cyber peace has slipped into the lexicon, beginning around 2008, the term has been used differently by the several interlocutors who draw upon it. Cyber peace is sometimes understood as a social condition or quality, sometimes as a set of practices, and sometimes as both. In this section, I interpret some core texts to tease out differences between the meanings and discuss the theoretical consequences of the differences.Footnote 3

In drawing upon a text, I do not mean to imply that my short selections are representative of everything authors think about cyber peace, or that their definition is incorrect. Instead, I use these different articulations to show the variety of ways cyber peace is imagined. Highlighting the unsettledness of the essence of cyber peace is the point of the exercise.

3 The Condition of Cyber Peace

An early use of the word “peace” in the context of cyberspace and the Internet is a 2008 forward written by the former Costa Rican president and Nobel laureate, Óscar Arias Sánchez, for the International Telecommunications Union’s (ITU) report on the ITU’s role in cybersecurity (Arias Sánchez, Reference Arias Sánchez2008). He referred to the need to promote “peace and safety in the virtual world” as “an ever more essential part of peace and safety in our everyday lives” and the urgency of creating a “global framework” to provide cybersecurity (p. 5). He implied that this safe place within cyberspace can be implemented through intergovernmental coordination around cybersecurity practices. The result would be to create the condition of feeling secure, very much along the lines of what one expects from the concept of “human security” (Paris, Reference Paris2001; United Nations Development Program, 1994). Techniques, such as the adoption of cybersecurity best practices, Arias suggested, are tools that promote this safe world, but these tools are not themselves cyber peace. In context, it seems that peace and safety are not two separate goals but rather one: Safety as peace – either as a kind of peace or perhaps as a part of peace.

Ungoverned cyberspace is dangerous because of “the pitfalls and dangers of online predators” (Arias Sánchez, Reference Arias Sánchez2008, p. 4) who inhabit it. As a state of (albeit non-) nature, it is a Hobbesian (Hobbes, Reference Hobbes1651) world of war and crime or, more precisely, the disposition toward violence which could break out at any time. This ungoverned, dangerous world of cyberspace is to be cordoned off and, perhaps, eliminated. Global coordination on cybersecurity is thus essential to promote the condition of safety.

Hamadoun Touré, writing in the introduction to The Quest for Cyber Peace, a joint publication of the ITU and the World Federation of Scientists (WFS), similarly seems to draw upon this Hobbesian view of ungoverned cyberspace when he writes that “[w]ithout mechanisms for ensuring peace, cities and communities of the world will be susceptible to attacks of an unprecedented and limitless variety. Such an attack could come without warning” (2011, p. 7). He continues, enumerating some of the devastating effects of such an attack. Touré’s description suggests that conditions of cyberspace could break the security provided by the sovereign state (the leviathan) to its citizens. Violence is lurking just under the surface of our cyber interactions, waiting to break out. Touré, in a policy suggestion consistent with some liberal institutionalists’ thinking in international relations, understands the potential of an international regimeFootnote 4 (though he does not use that term) of agreed-upon rules that would provide the condition of cyber peace in the absence of a single authoritative ruler. Arias and Touré both envision cyberspace as having a zone of lawlessness and war and a zone of safety and peace.

Henning Wegener’s (Reference Wegener and Touré2011) chapter in The Quest for Cyber Peace defines cyber peace more expansively than Touré did. More importantly, Wegener’s ontology is subtly different from the division of cyberspace into the peaceful and violent zones I associated with Arias and Touré. Wegener writes:

The starting point for any such attempted definition must be the general concept of peace as a wholesome state of tranquility, the absence of disorder or disturbance and violence – the absence not only of “direct” violence or use of force, but also of indirect constraints. Peace implies the prevalence of legal and general moral principles, possibilities and procedures for settlement of conflicts, durability and stability.

We owe a comprehensive attempt to fill the concept of peace – and of a culture of peace – with meaningful content to the UN General Assembly. Its “Declaration and Programme of Action on a Culture of Peace” of October 1999 provides a catalogue of the ingredients and prerequisites of peace and charts the way to achieve and maintain it through a culture of peace.

By identifying cyber peace as a kind of peace rather than as a carve out of cyberspace, Wegener shifts the focus away from cyberspace as the world in which cyber peace exists or happens and, instead, connects to the material reality of the geopolitical world. The distinction is illustrated in Figure 1.1. The image on the left represents the definition invoked by Arias and Touré. The image on the right represents the definition invoked by Wegener.

Figure 1.1 Different ontologies of cyber peace as conditions. On the left, both cyber peace and cyber war exist as kinds of social conditions within places of cyberspace. Cyber war is always attempting to penetrate and disrupt cyber peace. On the right, cyber peace is a subset of global peace, along with other kinds of peace.

4 Cyber Peace as Practices

Other interlocutors use the phrase “cyber peace” to refer to practices, which can range from using safer online platforms for cross-national communication to “cyber peace keeping” or “cyber policing” to engineering a robust, stable, and functional Internet. This approach is consistent with (though not intentionally drawing upon) what has been called the “practice turn” in international relations (Adler & Pouliot, Reference Adler and Pouliot2011; for example, Bigo, Reference Bigo2011; Parker & Adler-Nissen, Reference Parker and Adler-Nissen2012; Pouliot & Cornut, Reference Pouliot and Cornut2015). Practices constitute meaningful social realities because of three factors. First, it matters that human beings enact practices, because in doing so we internalize that action and it becomes a part of us. Second, there is both a shared and an individual component to practices. Individuals are agentic because they can act; the action has social relevance because others act similarly. Third, practices are constituted and reconstituted through patterned behavior; in other words, through “regularity and repetition” (Cornut, Reference Cornut2015). Since cyber peace is an aspiration rather than something that exists now, a practice theory focus could point toward emerging or potential practices and how they are accreting.

One example of this aspirational view of practices can be found in the 2008 report, “Cyber Peace Initiative: Egypt’s e-Safety Profile – ‘One Step Further Towards a Safer Online Environment’,” which defines cyber peace in terms of young people engaging in the practices of communicating and peacemaking.Footnote 5 According to Nevine Tewfik (Reference Tewfik2010), who summarized the findings in a presentation to the ITU, information and communications technologies (ICTs) “empower youth of any nation, through ICT, to become catalysts of change.” These practices would then result in a more peaceful condition in geophysical space. Specifically, the end result would be “to create safe and better futures for themselves and others, to address the root causes of conflict, to disseminate the culture of peace, and to create international dialogues for a harmonious world” (p. 1). The report emphasized the initiative’s efforts to promote safety of children online. An inference I draw from the presentation slides is that the dissemination of the culture of peace happens when children can engage safely with each other online. Cyberspace can be a place where children – perhaps because of their presumed openness to new ideas and relations – engage in peacemaking. Thus, the benefits of the prescribed cyber peace activities would spill over into the geophysical world.

Cyber peace is often defined as practices that maintain the stability of the Internet and connected services. (The tension between stability and peace will be discussed later.) Drawing on this definition leads advocates to argue for prescriptions of protective behaviors and proscriptions of malign behaviors to maintain the functional integrity of the global ICT infrastructure. Key to this is the connection between a stable global network of ICTs and the ability to maintain peaceful practices in the geophysical world. The WFS, for example, had been concerned with all threats to information online (“from cybercrime to cyberwarfare”), but the organization’s permanent monitoring panel on information security “was so alarmed by the potential of cyberwarfare to disrupt society and cause unnecessary harm and suffering, that it drafted the Erice Declaration on Principles of Cyber Stability and Cyber Peace” (Touré & Permanent Monitoring Panel on Information Security of the World Federation of Scientists, Reference Wegener and Touré2011, p. vii). The declaration states: “ICTs can be a means for beneficence or harm, hence also as an instrument for peace or for conflict” and advocates for “principles for achieving and maintaining cyber stability and peace” (Permanent Monitoring Panel on Information Security of the World Federation of Scientists, 2009, p. 111). These principles about how to use ICTs are, in fact, practices. By adhering to the principles and acting properly, engagements in cyberspace and ICTs promote peace in the world. The declaration seems to refer to a general condition combining life as normal without the disruptions that warlike activities cause to “national and economic security,” and life with rights, that is human and civil rights, “guaranteed under international law.”

In other words, for this declaration stability is a desired characteristic of cyberspace and peace is a desired characteristic of life in the world as a whole. However, it does not follow that stability is inherently peaceful, unless peace is tautologically defined as stability. The absence of cyber stability might harm peace and the presence of cyber stability might support peace, but the presence of stability is not itself peaceful, nor does it generate peace.Footnote 6 At best, we can say that peace is usually easier to attain under conditions of stability.

Another text focusing on cyber peace as a set of practices is the Cyberpeace Institute’s website. It first calls for “A Cyberspace at Peace for Everyone, Everywhere,” which seems to hint at cyber peace as a condition of global society, but the mission of the organization is defined primarily as the capacity to respond to attacks, and only secondarily as strengthening international law and the norms regarding conflictual behavior in cyberspace. Indeed, defense capacity is emphasized in the explanation that “The CyberPeace Institute will focus specifically on enhancing the stability of cyberspace by supporting the protection of civilian infrastructures from sophisticated, systemic attacks” (CyberPeace Institute – About Us, 2020). The ability to mount a swift defense in response to an attack does not create peace, it simply means that our defenses may be strong enough that the attacks do not disrupt the stability of the Internet and other information technologies.

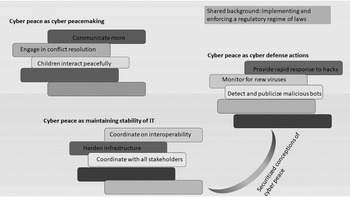

These conceptualizations of cyber peace as collections of practices thus ontologize kinds of cyber peace, which are distinct, but comparable. By comparing them, we can see underlying tensions regarding what can be considered peaceful – Is it peace making or securitization (defense and stability)? – though, as noted in the descriptions above, no collection of practices is wholly of one type. Figure 1.2 depicts different collections of practices that have been bundled together as the definition of cyber peace. (For clarity, I have not shown overlaps.) All of these conceptualizations are proposed against a background of a regulatory regime of implementing and enforcing laws.

Figure 1.2 Cyber peace as the sum of practices in both securitized and non-securitized conceptualizations, against a shared background of implementing and enforcing a regulatory regime of laws.

5 Cyber Peace as Both Conditions and Practices

A third category blends conditions and practices, seeing the condition of cyber peace emerge as greater than the sum of its constituent parts, which are practices. In an early iteration of his work on this concept, Scott Shackelford (Reference Shackelford2014) paints this sort of hybrid picture of cyber peace. He claims that the practices of polycentric governance related to cybersecurity spill over into a positive cyber peace:

Cyber peace is more than simply the inverse of cyber war; what might a more nuanced view of cyber peace resemble? First, stakeholders must recognize that a positive cyber peace requires not only addressing the causes and conduct of cyber war, but also cybercrime, terrorism, espionage, and the increasing number of incidents that overlap these categories.

This can happen, Shackelford suggests, through a process of building up governance on limited problems, thereby proliferating the number of good governance practices. The polycentric governance model specifically rejects a top-down monocentric approach:

[A] top-down, monocentric approach focused on a single treaty regime or institution could crowd out innovative bottom-up best practices developed organically from diverse ethical and legal cultures. Instead, a polycentric approach is required that recognizes the dynamic, interconnected nature of cyberspace, the degree of national and private-sector control of this plastic environment, and a recognition of the benefits of multi-level action. Local self-organization, however – even by groups that enjoy legitimacy – can be insufficient to ensure the implementation of best practices. There is thus also an important role for regulators, who should use a mixture of laws, norms, markets, and code bound together within a polycentric framework operating at multiple levels to enhance cybersecurity.

These interconnected, overlapping, small to medium-scale governance practices build upward in Shackelford’s model and could eventually become a thick cybersecurity regime. When the regime is thick enough, cyber peace obtains. This model relies on a securitized notion of cyber peace, despite the discussion in the text of positive cyber peace that is more far-reaching than just the absence of war. His more recent work, co-authored by Amanda Craig, expands cyber peace to include global peace-related issues and practices, including development and distributive justice. They write:

Ultimately, “cyber peace” will require nations not only to take responsibility for the security of their own networks, but also to collaborate in assisting developing states and building robust regimes to promote the public service of global cybersecurity. In other words, we must build a positive vision of cyber peace that respects human rights, spreads Internet access alongside best practices, and strengthens governance mechanisms by fostering global multi-stakeholder collaboration, thus forestalling concerns over Internet balkanization.

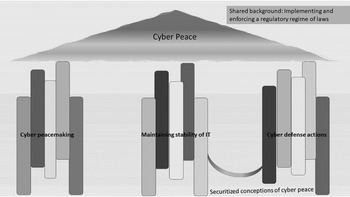

Figure 1.3 depicts this model of best practices developed from the ground up, ultimately producing a kind of cyber peace that exceeds the summation of all the different practices.

Figure 1.3 Peaceful practices and shared background emerge as cyber peace, which is greater than the sum of its parts.

The point of this exercise of categorizing different definitions of cyber peace is to say that a definitional consensus has not been reached and to remind ourselves that the ontology built into our definitions matters for how we think about what sounds like a very good goal. Moreover, ontological foundations matter for how the practitioners among us craft policies in pursuit of that goal.

6 Honing the Concept of Cyber Peace

The four parts of this section critically engage further with cyber peace, pointing to conceptual elements that could be productively honed to make a sharper point. The point here is not to provide an answer of what cyber peace is or should be but, rather, to draw upon scholarship from international relations and cognate fields to uncover contradictions and missed implications of the current usage. I begin by taking a closer look at “cyber” and “peace” and then turn to the boundaries of cyber peace as a social thing, followed by a discussion of the consequences of some of the metaphors associated with cyber peace.

6.1 Unpacking the “Cyber” Element

“Cyber” is a shortening of “cybernetics,” a term introduced by Norbert Wiener, who used it to refer to the control of information machines and human groups. He emphasized: “Cybernetics takes the view that the structure of the machine or of the organism is an index of the performance” (Wiener, Reference Wiener1988, p. 57; italics in original) because the structures – that is, the properties of the machine or organism – determine what the machine or organism is able and unable to do, and what it is permitted to do, must do, and must not do. Cybernetics concerns control and order; its purpose is to be a bulwark against disorder and entropy. The shortened form quickly came to connote that which involves computers and information technology. “Cyberspace,” famously introduced in Neuromancer by William Gibson (Reference Gibson1994), rapidly became the narrative means of reimagining a communications technology (the Internet) as a place (albeit a heterotopia [Foucault, Reference Foucault1986; Piñuelas, Reference Piñuelas2008]) in which or on which people (reimagined as users) do things and to which they go. As discussed in the section on cyberspace as a condition, we then imagine cyberspace to be a state of (non-) nature apart from the real-life physical world we live in, and we think of it as dangerous because it is ungoverned or incompletely governed. Some instances of cybercrime give credence to that, though such crimes may well be subject to law enforcement by real-life police or others. The irony is that although the cyber refers to the realization of control, cyberspace is thought of as a place of lack of control, as David Lyon (Reference Lyon2015) has recognized.

More recent morphing of the usage of “cyber” turns it into a noun associated with military activity using information technology-intensive tools. This particular nominalization immediately calls to mind warnings from securitization theory (Balzacq, Reference Balzacq2005; inter alia, Buzan, Reference Buzan1993; Hansen, Reference Hansen2000; Waever, Reference Waever1996). The theory focuses on how language constrains our thinking and specifically on how language recasts situations, people, processes, relations, etc. as security threats, and leads to a creeping expansion of control by institutions that command the use of force. This should be understood as a danger rather than a deterministic outcome,Footnote 7 and I am not arguing that we should excise “cyber” from the dictionary. But I am mindful of the securitizing language that drags the concept of cyber peace back toward a sort of negative peace. As Roxanna Sjöstedt (Reference Sjöstedt2017) puts it, “If you construct a threat image, you more or less have to handle this threat.”

In short, “cyber” is complicated. The word connotes the constitution of a space outside our ordinary existence in geographical space. Cyber implies order in the form of efficient control through code and other engineered rules that ought to work well. Yet cyber also hints at disorder and even chaos, since rules are often circumvented. Additionally, the military’s appropriation of cyber as a shortening of “cyber conflict” or “cyber war” risks turning cyber peace into an oxymoron, taking on the sense of martial peace. That linguistic change may condition thinking and securitize the very thing that ought to be desecuritized.

6.2 Unpacking the “Peace” Element

If anything, peace is even more complicated than cyber. Peace is the main focus of the entire field of peace studies, and it is also an important topic for scholars of conflict management and conflict resolution, as well as of international relations more broadly. Peace always sounds good – better than war, at any rate.Footnote 8 But the war-peace dichotomy may hide the definitional complexity. Johann Galtung differentiates between “negative peace,” understood as the absence of violence in a relationship and “positive peace,” a more complex term that is often used to refer to relations that are just, sustainable, and conducive human flourishing in multiple ways (see also Shackelford, Reference Shackelford2016). In its most expansive connotation, the relationship of positive peace is tied to peacebuilding and, ultimately, to amity. The main thrust of this volume envisions cyber peace as positive cyber peace. But the caveats articulated by Paul Diehl (Reference Diehl2016, Reference Diehl2019) about positive peace and its usefulness as a social type of thing are worth considering. He notes, first of all, the lack of consensus among positive peace researchers about what is actually included in it:

Conceptions include, among others, human rights, justice, judicial independence, and communication components. Best developed are notions of “quality peace,” which incorporate the absence of violence, but also require things such as gender equality in order for societies to qualify as peaceful (2019).

The lack of clarity over what positive peace is has, Diehl suggests, epistemological consequences.

Many of [the things that are required for societies to qualify as peaceful], however, lack associated data and operational indicators. Research on positive peace is also comparatively underdeveloped.Footnote 9

While Diehl finds the concept of positive peace desirable, he warns that the concept is underdeveloped in three important ways, and each of these resonates with considerations about cyber peace.

First, what are the dimensions of peace and why is so little known about how the many dimensions interact? His concern should provoke cyber peace theorists to consider whether the four pillars are dimensions in Diehl’s terms and, if so, whether they comprise all the dimensions. Given the potential for multiple dimensions of peace, perhaps only some are required for the situation to be deemed peaceful. Alternatively, perhaps cyber peace is actually an ideal type, and the different dimensions make a situation more or less cyber peaceful.

Second, Diehl also raises the concern about an undertheorized assessment of how positive peace varies across all forms of social aggregation (“levels of analysis” in international relations scholarship). How does positive peace manifest differently in different contexts? For cyber peace, this critique points to the not fully developed idea of how the scale works in cyberspace and how that matters. A neighborhood listserv is different from Twitter, but shares some characteristics relevant to peace – flame wars and incivility are a problem in both environments. But the risks of manipulation of communication by foreign adversaries on Twitter and the kinds of policies that would be required to make peace on Twitter means, I suggest, that the environment of cyberspace is similarly complicated with regard to scale.

Third, Diehl (Reference Diehl2019) notes that “some positive peace concepts muddle the distinction between the definitional aspects of peace and the causal conditions needed to produce peaceful outcomes.” I think that the four cyber peace pillars may fall prey to this lack of conceptual clarity and, perhaps, to a sort of tautology.

7 Boundaries

The next topic is boundaries and the distinctions that create them. An argument can be made that we are witnessing the creation of cyber peace as a new social entity, a thing. Andrew Abbott (Reference Abbott1995) suggests new things emerge through a process of yoking together a series of distinctions. This is an iterative process of asking what are the characteristics of the new thing and what are not? “Boundaries come first, then entities” (p. 860). Cyber peace has yet to cohere into the sort of enduring, reproducing institution that would count as one of the Abbott’s new social entities, but we do see the setting of “proto-boundaries” that may become stable when we examine the processes of trying to name and implement cyber peace. In this section, I discuss three “points of difference” that are important for the concretization of cyber peace: Between (1) cyber peace and cyber aggression, (2) cyber peace/aggression and cyber lawfulness/crime, and (3) associating multistakeholder cyber governance with cyber peace and (implicitly) associating other forms of cyber governance with non-cyber peace.

A basic distinction is between the common sense understanding of what constitutes cyber peace versus cyber aggression. The case of the 2007 cyberattack against Estonia is a clear example of cyber aggression. A more complicated case is Stuxnet, the malicious computer worm discovered in 2010, which was deployed against computer equipment used in the Iranian nuclear program. One interpretation of the Stuxnet operation would name it cyber aggression. A different interpretation would find the use of this cyber weapon de-escalatory when considered in its broader geopolitical context. Stuxnet decreased the rapid ramping up of Iran’s ability to develop nuclear arms, which made an attack with full military force unnecessary. On the one hand, information technology was used for a hostile purpose. On the other, the targeted cyber attack removed a significant threat with apparently no loss of life (though the spread of the worm through networks resulted in monetary losses). Perhaps in this case it makes sense to think of the possibility that Stuxnet was actually consistent with cyber peace. (See also Brandon Valeriano and Benjamin Jensen’s assessment of the potential de-escalatory function of cyber operations in Chapter 4 of this volume.)

But is it possible to thread that needle – to use low-intensity, carefully targeted cyber operations (limiting their harmful consequences) to avoid more hostile interventions – as a matter of strategy? And if so, do such actions promote cyber peace? The 2018 United States Department of Defense cyber strategy tries to do this with its “defend forward” approach to cyber security, and by “continuously engaging” adversaries (United States Cyber Command, 2018, pp. 4, 6). The implicit analogy to nuclear deterrence likely conditions decision makers’ expectations, in my view. As Jason Healey explains, proponents of the strategy seek stability through aggressiveness. They assert that “over time adversaries will scale back the aggression and intensity of their operations in the face of US strength, robustly and persistently applied” (2019, p. 2). But Healey is cautious – noting the risk of negative outcomes – as persistent engagement could produce an escalatory cycle. In short, further characterizing the nature of cyber peace requires achieving greater clarity in differentiating between the kinds of cyber aggression that promote more peaceful outcomes rather than less.

The second point of distinction creates a boundary between problems that involve criminal violations versus those that rise to the level of aggressive breaches of cyber peace. Unlike cyber aggression, cybercrime, I suggest, is not the opposite of cyber peace. The scams, frauds, thefts, revenge porn postings, and pirated software that are everyday cybercrimes seem to me to be very bad sorts of things, but as policy problems they generally fall into the category of not lawful, rather than not peaceful. A society can be peaceful or cyber peaceful even in the presence of some crime; all societies have at least some crime. Countering cybercrime requires cyber law enforcement and international collaboration to deal with transnational crimes. Countering cyber aggression requires efforts toward (re)building cyber peace. These might include diplomacy, deterrence, or – the less peaceful alternative – aggression in return. Automatically folding cybercrime into the category of things that threaten cyber peace risks diluting the meaningfulness of cyber peace.

A caveat must be added, however. The boundary between cybercrime and cyber aggression is complicated by what Marietje Schaake describes as “the ease with which malign actors with geopolitical or criminal goals can take advantage of vulnerabilities across the digital world” (2020, emphasis added). The “or” should be understood as inclusive: “and/or.” Cybercrimes can be used to attain geopolitical goals (acts of cyber aggression), criminal goals, or both. The 2017 “WannaCry” ransomware attack, attributed to North Korea, provides an example of both cyber aggression and cybercrime. Initially, WannaCry was assumed to be the work of an ordinary criminal, but once North Korea’s involvement became apparent, the evident geopolitical aim and the attack’s aggressiveness became more important. We would sort WannaCry and similar aggressive actions in the category of “threats” to cyber peace rather than into the category of (only) “not lawful.”

Yet cybercrimes can, paradoxically, be tools for cyber peace too. Cybercrimes involving activities in support of human rights provide oppressed individuals and groups opportunities to fight back against their oppressors. Circumventing repressive surveillance technology might be an example of this. In that case, breaking the law could, arguably, be an example of cyber peace rather than a difference from it.

Third, the cyber peace pillar on multistakeholder collaboration assumes a distinction between cyber peace and non-cyber peace in terms of forms of governance. The definition of cyber peace includes a strong preference for developing “governance mechanisms by fostering multistakeholder collaboration” (Shackelford, Reference Shackelford2016). Shackelford sees bottom-up multistakeholder governance as a form of polycentricity and as good in itself. But both polycentricity and multistakeholderism are problematic points of distinction for what is or is not cyber peaceful. Michael McGinnis and Elinor Ostrom (Reference McGinnis and Ostrom2012, p. 17), commenting on a classic article by Vincent Ostrom, Charles Tiebout, and Robert Warren (Reference Ostrom, Tiebout and Warren1961), call attention to how the authors:

[…] did not presume that all polycentric systems were automatically efficient or fair, and they never denied the fundamentally political nature of polycentric governance. The key point was that, within such a system, there would be many opportunities for citizens and officials to negotiate solutions suited to the distinct problems faced by each community.

A multistakeholder form of polycentric governance, however, involves not just citizens and officials negotiating solutions, but firms and other private actors as well, which potentially skews that political nature because the resources the different stakeholders have to draw upon in their negotiations can differ by orders of magnitude. As Michael McGinnis, Elizabeth Baldwin, and Andreas Thiel (Reference McGinnis, Baldwin and Thiel2020) explain, polycentric governance can come to suffer from dysfunction because of structural forms that allow some groups to have outsized control over decision-making processes. And this is certainly true for a cyberspace governance organization like the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN), where the industry interests have significantly more say in outcomes than users. Furthermore, whereas polycentric governance evolves organically out of efforts to solve problems of different but related sorts, multistakeholderism is designed into the governance plan from its initiation, as was clearly the case with ICANN.

Moreover, as Kavi Joseph Abraham (Reference Abraham2017) explains, stakeholderism is actually not about creating better forms of democratic governance. Rather, its origin story can be traced to “systems thinking” in engineering and related management practices that emphasized the need for control of complexity. Complex systems, as engineers came to understand, involved multiple inputs, feedback loops, contingencies, outputs, etc. Controlling such systems required coordination of all those factors. That idea of coordinating all inputs into processes spilled over into the academic field of business management, where the firm came to be seen as a complex system. Control involved the coordination of material inputs plus the coordinated activity and decision-making of people – workers, managers, customers, shareholders, suppliers, communities affected by effluents from the firm’s factory, etc. Groups that had a role to play were thus identified as “stakeholders,” but unlike the assumed equality of citizens in a democracy, there was never any assumption that stakeholders should be equal or equivalent. Managing is about dealing with complexity, not about governing while protecting rights. We should not assume that multistakeholderism is uniquely suited to be the governance form for cyber peace.

8 Metaphors

Finally, I raise the issue of metaphors and how they enable and limit thinking in some way (Cienki & Yanow, Reference Cienki and Yanow2013; Lakoff & Johnson, Reference Lakoff and Johnson1980). First, is cyber peace the right metaphor that describes the sought-after goal? How would cyber peace be different from cyber order, cyber community, or cyber health? Given that much of the activity that goes on in cyberspace is commercial and given that commercial transactions are generally competitive rather than peaceful, does it make sense to talk about cyber peace when the goal is not friendly relations but, rather, a competitive market in which exchange can happen without the disruption of crime? How is cyber peace distinct from a well-functioning cyber market? Yet another alternative would be to rethink the marketization of cyberspace and to imagine instead a regulated utility and the provision of cyber services to the global public.

Moreover, by invoking peace in the context of what is often intended to be best practices of cyber security to maintain a stable Internet we fall prey to “inadvertent complicity” (Alker, Reference Alker1999, p. 3), distracting attention from real violence. Overusing the peace metaphor flattens the differences between deeply consequential and ethically crucial peacemaking in the world, and getting people to use better passwords. We can see this flattening dynamic even when considering initiatives promising to save lives (anti-cyberbullying initiatives as a cyber peace practice, for example). I think cyberbullying is truly awful, and in the United States, it is a crime. It is often also a mental health challenge, both for the bully and bullied. It’s a social pathology and a behavioral problem. It is also a cyber governance issue, as E. Nicole Thornton and I discussed in an article on the difficulties faced by owners of social media websites trying to prevent hijacking of their sites by bullies (Marlin-Bennett & Thornton, Reference Marlin-Bennett and Thornton2012). But is it useful to think of cyberbullying as a violation of cyber peace? (And doesn’t doing so give the bully too much power?) Cyber peace becomes hyperbole, notwithstanding the well-meaning campaigns such as that of the Cyber Peace Foundation (CyberPeace Corps, 2018). Peace is a strong word. By invoking peace (and war by implication), context and historicity can be washed away, obscuring the difference between cyberbullying and Russian cyber election disruptions that threaten to do grave harm to democracies.

9 A Final Thought

In the oft-cited special issue of International Organization on international regimes, the final article was written by Susan Strange (Reference Strange1982). The title was “Cave! hic dragones: a critique of regime analysis.” A note in smaller type at the bottom of the page reads “The title translates as ‘Beware! here be dragons!’ -an inscription often found on pre-Columbian maps of the world beyond Europe.” The article, she explains in the first paragraph, does not ask “what makes regimes and how they affect behavior, it seeks to raise more fundamental questions about the questions.” Her intent, instead, was to ask whether the regime concept is at all a useful advance for international political economy and world politics scholarship. She famously decided that the concept of the international regime was a bad idea for seven reasons (five main and two indirect). She was wrong. The concept of the international regime has endured and is widely accepted, and it has been useful. But I do not think that the concept of an international regime would have been nearly as well integrated into our scholarly lexicon now if it had not been for Strange’s intervention. Over the subsequent years, proponents of the regime concept had to work to improve the concept to counter her claims, which were really quite fair, if expressed bluntly.

I do not have as negative an opinion of cyber peace as Strange did of international regimes, but her charge that the concept of international regimes was “imprecise and woolly” seems to fit the concept of cyber peace, as well. By analyzing the different meanings ascribed to cyber peace, I hope to do what Strange, intentionally or not, did for regimes theory: Make it better.

Introduction

The Chinese government has reportedly detained over a million Muslims in the northwestern region of Xinjiang (Maizland, Reference Maizland2019). The detainees, predominantly of the Uighur ethnic group, are being held in reeducation camps where they are forced to pledge loyalty to the Communist Party of China, renounce Islam, and learn Mandarin (Maizland, Reference Maizland2019). Officials in China purport that these camps are not only used for vocational training, but also cite the need to quell the influence of violent extremism in the Xinjiang population (Maizland, Reference Maizland2019). There are reports of prison-like conditions in these camps, including extensive surveillance, torture (Wen & Auyezov, Reference Wen and Auyezov2018), and even forced sterilization (Associated Press, 2020). The Uighur population is also under extensive surveillance outside of these detention facilities. Alleged monitoring has included location surveillance through messaging apps such as WeChat, facial recognition technology used at police checkpoints, as well as biometric monitoring (Cockerell, Reference Cockerell2019). These technologies are being used by the Communist Party as new digital tools for monitoring and controlling populations deemed threatening to the Chinese state.

Modern digital information and telecommunication technologies (ICTs) have changed the ways in which states and their citizens interact on a variety of fronts, including the provision of goods and services and the production of information and misinformation. As the case of the Uighur population in China suggests, ICTs have also changed the ways in which states address threats from their population. While these kinds of overt, blatant abuses carried out by authoritarian states against ethnic or religious minorities tend to capture much attention, the use of digital technologies for repression is by no means limited to authoritarian states (Dragu & Lupu, Reference Dragu and Lupu2020). New technologies are shifting the ways in which all states, democratic as well as authoritarian, repress.

While improvements in technology have often been associated with liberation, digital technologies in the hands of governments willing to repress can be a major threat to respect for human rights and freedoms worldwide and, as such, they are a danger to cyber peace. As defined in the Introduction to this volume, a positive cyber peace necessitates respect for human rights and freedoms and the spread of Internet access. These characteristics are threatened by domestic digital repression, which often includes intentionally limiting access to the Internet and cellular communications, and can both constitute and facilitate violations of human rights and freedoms. Our chapter focuses on the changing nature of repression through digital technologies as a risk to cyber peace. Differing from other contributions to this volume (see Chenou & Aranzales, Chapter 5), we explore the domestic side of the interaction between digital technologies and cyber peace. Digital technologies are transforming repression, but we still know very little about this transformation and its long-term impact on state behavior. We believe, however, that understanding the ways in which these technologies are reshaping state power and its relationship to its citizens is necessary to build a more peaceful and freer digital and analog world.

In this chapter, we provide a conceptual map of the ways in which ICTs impact state repression. This mapping exercise seeks to identify some initial sites of influence in order to further theorize and empirically evaluate the effects of ICTs on our current understandings of state repression. We begin by outlining a conceptual definition of digital repression informed by the extant literature on state repression. We then derive four constituent components of state repression and trace the impact of ICTs on each of our four components.Footnote 1 In conclusion, we discuss how our findings may inform or upend existing theories in the study of state repressive behavior.

1 Repression and Digital Repression

State repression refers to the actual or threatened use of physical violence against an individual or organization within a state for the purpose of imposing costs on the target and deterring specific activities believed or perceived to be threatening to the government (Goldstein, Reference Goldstein1978, p. xxvii). Traditional modes of repression have been conceptualized based on their impact on the physical integrity of groups or individuals, or as restrictions on individual or group civil liberties. Physical integrity violations refer to violations of a person’s physical being such as enforced disappearances, torture, or extrajudicial killings. Civil liberties violations include restrictions on press freedoms and information, and freedoms of association, movement, or religious practice.

All states repress, albeit in different ways and for different reasons (Davenport, Reference Davenport2007). Most scholars of state repression view the decision to repress as a rational calculus taken by political authorities when the costs of repression are weighed against its potential benefits (e.g., Dahl, Reference Dahl1966; Goldstein, Reference Goldstein1978; Davenport, Reference Davenport2005). When the benefits of repression outweigh the costs, then states are likely to repress. The expected benefits of using repression are “the elimination of the threat confronted and the increased chance of political survival for leaders, policies, and existing political-economic relations” (Davenport, Reference Davenport2005, p. 122). In addition, repression may demonstrate strength and deter subsequent threats. Traditional costs of repression, on the other end of the equation, include logistical and monetary costs, as well as potential political costs. The literature on the dissent–repression nexus suggests that while repression may neutralize a threat in the short term, it has the potential to yield to more dissent in the longer term because of a backlash effect to state policies (Rasler, Reference Rasler1996; Koopmans, Reference Koopmans1997; Moore, Reference Moore1998; Carey, Reference Carey2006). Democratic leaders who use particularly violent forms of repression may be penalized by voters (Davenport, Reference Davenport2005). Furthermore, leaders may suffer external political costs; for example, the international community may sanction leaders for excessive use of force against their civilian populations, or for behaviors that violate international human rights norms (Nielsen, Reference Nielsen2013).

The advent of modern digital technologies has ushered in new forms of digital repression. Digital repression is the “coercive use of information and communication technologies by the state to exert control over potential and existing challenges and challengers” (Shackelford et al., in this volume, Introduction). Digital repression includes a range of tactics through which states use digital technologies to monitor and restrict the actions of their citizens. These tactics include, but are not limited to, digital surveillance, advanced biometric monitoring, misinformation campaigns, and state-based hacking (Feldstein, Reference Feldstein2019). Modes of digital repression map onto the two modes of traditional repression mentioned above, physical integrity and civil liberties violations. Digital repression, while not directly a physical integrity violation, can facilitate or lead to such types of violations. For example, the data gathered by the Chinese state about the Uighur population has aided the government in locating and physically detaining large numbers of Uighurs. Digital repression can constitute both a civil liberties violation in and of itself, and facilitate the violation of civil liberties. For example, by limiting individual access to information and communication, the state violates the rights of citizens to access information. Alternatively, by closely monitoring the digital communications of social movements, states can deter or more easily break up political gatherings and protests. While states regularly gather and rely upon information about their citizens to conduct the work of governing, digital repression entails the use of that information for coercive control over individuals or groups that the state perceives as threatening.

As with traditional forms of repression, the use of digital repression can be seen in terms of a cost–benefit calculus on the part of the state. Yet, in the case of digital repression, this calculus is not well understood. Digital technologies impact the ways in which states identify and respond to threats, as well as the resources needed to do so. New technologies also impact the ways in which challengers, citizens, and the international community will experience and respond to the state’s behavior, in turn, affecting the costs and benefits of using digital repressive strategies. For example, the costs of digitally monitoring social movement participation through social media may have large upstart costs in terms of infrastructure and expertise. Yet, those initial costs may be offset over future threats. In certain circumstances, digital repression may reduce audience costs associated with traditional forms of repressionFootnote 2 as these newer forms of repressive behavior may be easier to disguise. Alternatively, if digital repression is hidden from the public, it may be less likely to deter future threats, as challengers may not fully understand the levels of risk involved in challenging the state. In sum, it is likely that digital repression is shifting the cost–benefit analysis of state repression. However, we have yet to adequately theorize how this analysis might differ from, and relate to, a cost–benefit analysis of the use of traditional state repression.

Before we map how ICTs are reshaping state repression, we first place some scope conditions on the set of technologies that are relevant for our inquiry. Within the last decade, scholars have begun to develop frameworks and explore empirical patterns related to digital repression in a still nascent literature.Footnote 3 This work has examined a wide range of technologies, strategies, and platforms, including Internet outages (Howard et al., Reference Howard, Agarwal and Hussain2011), social media use (Gohdes, Reference Gohdes2015), and surveillance technologies (Qiang, Reference Qiang2019). Building on this work, we focus on the technological developments that facilitate two kinds of activities: (1) access to new and potentially diverse sources of information and (2) near instantaneous communication among individual users. While neither of these activities is a fundamentally new use of technology, the volume of information available, the number of individuals that can access and communicate information, and the speed at which exchanges can occur are new. Therefore, we are interested in ICTs that combine cellular technology, the Internet and its infrastructure, the software and algorithms that allow for large-scale data processing, and the devices that facilitate access to the Internet (e.g., computers and smart phones).Footnote 4

As Shackelford and Kastelic (Reference Shackelford and Kastelic2015) detail, as states have sought to protect critical national infrastructure from cyber threats, they have pursued more comprehensive state-centric strategies for governing the Internet. This has led to the creation of national agencies and organizations whose purpose is to monitor communication and gather data and information about foreign as well as domestic ICT users. This is true for both democracies and autocracies. But whereas we tend to associate democracies with robust legal protections and strong oversight institutions (especially with respect to the private sector), we do not need to travel far to find cases of democracies with timid approaches to oversight and protection of individual rights – the obvious example is the US government’s reluctance to reign in technology giants such as Apple or Facebook. Once governments gather information about users, they can engage in two kinds of activities that may lead to violations of citizen’s rights through either physical integrity or civil liberties violations. First, states can monitor and surveil perceived existing or potential threats. Second, states can limit access to ICTs or specific ICT content for individuals or groups perceived to present a threat to the state. The monitoring of threats and restrictions on threatening behavior are not new behaviors for states. However, digital technologies provide new opportunities for states to exercise control.

2 The Impact of ICTs on State Repression

We argue that state repression requires four specific components to function effectively. First, a state must have the ability to identify a threat. Second, the state must have the tactical expertise to address the threat. Third, a state must be able to compel responsive repressive agents to address a threat in a specified way. And fourth, the state must have a physical infrastructure of repression that facilitates addressing the threat, or at least does not make addressing the threat prohibitively costly. Below we discuss these components of repression and conceptualize the potential impacts of ICTs on each.

2.1 Threat Identification

Governments engage in repression in order to prevent or respond to existing or potential threats. The first component of repression, therefore, requires the state to be able to effectively identify and monitor these threats. Identifying and monitoring threats is costly. These costs are largely associated with gathering information which, depending on the nature of the threat, are likely to vary. Costs vary depending on whether the government is responding to an existing and observable threat (such as a protest or riot, or formal political opposition) or whether the government is attempting to detect a potential threat, which could be more difficult to identify.

Threat identification requires that governments have cultural, linguistic, and geographic knowledge (Lyall, Reference Lyall2010). The costs associated with gathering this kind of knowledge vary depending on context (Sullivan, Reference Sullivan2012). For example, there are urban/rural dynamics when it comes to threat identification. In some circumstances, it is easier for the state to monitor threats in an urban center, which may be close to the political capital, rather than in the hinterland, where geographic barriers could hinder information collection (Herbst, Reference Herbst2000). Conversely, in other contexts, urban concentrations may make it more costly to identify and isolate a particular threat. The size of a potential threat also impacts the costs of threat identification. Mass surveillance of the Uighur population, for example, requires the identification and monitoring of approximately twelve million people.

In both traditional forms of state repression and digital repression, information is central to identify existing and potential challenges to the state. Digital technologies offer the possibility of significantly lowering the costs of information collection for the state. The speed and volume with which information can be collected and processed is far greater than with any monitoring or surveillance techniques of the past. Moreover, as Deibert and Rohozinski (Reference Deibert and Rohozinski2010, p. 44) write, “Digital information can be easily tracked and traced, and then tied to specific individuals who themselves can be mapped in space and time with a degree of sophistication that would make the greatest tyrants of days past envious.” Individuals leave digital footprints, online or through cellular communication, with information that ties them to specific beliefs, behaviors, and locations. States can also track a much broader section of the population than was ever previously possible. For example, states threatened by mass mobilization can now closely monitor, in real time, crowd formations with the potential to become mass rallies, allowing police to be put on standby to immediately break up a protest before it grows (Feldstein, Reference Feldstein2019, p. 43).

The availability of less overt forms of threat detection may open up new strategic possibilities for governments, shaping their choice among forms of digital repression as well as between digital and traditional repression. For example, it is possible that a state would refrain from using certain monitoring tactics that are visible and attributable to the state, not because they would be useless in identifying a particular threat, but because the government does not want to tip its hand about its repressive capacity. In this circumstance, a government might choose to monitor a population, for example, rather than engage in mass incarceration. Still, digital technologies for threat identification also carry costs. The Xinjian authorities, for example, reportedly budgeted more than $1 billion in the first quarter of 2017 for the monitoring and detention of the Uighur population there (Chin & Bürge, Reference Chin and Bürge2017). However, this figure is likely lower than the amount the Chinese state would have spent to construct a comparable system without using digital technologies (Feldstein, Reference Feldstein2019, pp. 45–46). Furthermore, once those investments have been made, a form of path dependence is likely to ensure that the new expertise will continue to lead to particular forms or repression (as we discuss in the next section on tactical expertise).

The ability to access more, indeed enormous, amounts of information has the potential to increase the cost of threat identification. In fact, such volume of searchable data raises the challenge of identifying a threatening signal in an ever growing pile of digital noise. The problem, then, is not simply finding a signal, but the possibility that more digital noise could result in biased or wrong signals. Digital surveillance is often a blunter monitoring tool than individual surveillance techniques of the past, given the quantity of digital information which is now available. However, the development of algorithms and reliance on artificial intelligence for sifting through large amounts of information can significantly lower threat identification costs for states. But such tools, in turn, require new forms of tactical expertise. We discuss this issue in the next section.

2.2 Tactical Expertise

Once a threat has been identified, in order to repress effectively the state must have the ability to address the threat. Tactical expertise refers to the actual know-how of repression – that is, the skillsets developed by the state to exert control, ranging from surveillance techniques to torture tactics. A number of studies demonstrate that repressive tactics are both taught and learned (see, e.g., Rejali, Reference Rejali2007). Understanding the tactical expertise of a state when it comes to repression can tell us not only about the ability of the state to repress in the first place, but also about the type of repression the state is most likely to engage in when faced with a particular threat. Each state will have a specific skillset that enables it to repress in certain ways, but not in others. Certain techniques of repression may be unavailable to a state, or they would require the costs of appropriating a new skill. States may or may not be able to incur those costs. For example, states may invest in becoming experts at torture or, instead, they might invest in tools of riot policing. The “coercive habituation” of a state suggests that, if the state has engaged in repression or a type of repression in the past, this lowers the costs of applying the same form of repression in the future (e.g., Hibbs, Reference Hibbs1973; Poe & Tate, Reference Poe and Tate1994; Davenport, Reference Davenport1995, Reference Davenport2005). Therefore, the likelihood of becoming proficient at a particular repressive tactic is (at least in part) a function of the state’s history of threats and threat perception, as well as the history of the state’s response to these threats. We expect states to have varying levels of expertise across a variety of coercive tactics. These levels of expertise are reflected in the training centers, organizational infrastructure, and command structure of particular governmental actors charged with implementing repressive tactics.

Digital repression requires technological knowhow or expertise. This might be reflected in the availability of experts trained in information technology, fixed network and mobile technologies, or critical systems infrastructure. Technological expertise ultimately corresponds to the country’s reservoir of expert knowledge in the use, maintenance, and control of ICT systems. Given the resource requirements of acquiring this form of expertise in order to implement certain forms of digital repression, some governments may be unable or unwilling to incur the costs of developing the relevant skillset.

The relevant type and level of technological know-how required for digital repression varies based on who a state targets with digital repression, as well as what (if any) content is being restricted. Targets of digital repression can range from individual users to specific groups across specific geographic regions, or the whole country. States can also restrict access to, or publication of, information ranging from single websites to entire platforms or applications. In some cases, states can engage in a wholescale Internet or cellular communications blackout. Targeting individual users, as opposed to large swathes of the population, may be more costly as it requires a higher level of threat identification, and potentially greater levels of technical and algorithmic expertise. Similarly, targeting a specific website or single platform is often more costly and requires greater technical capacity than enforcing a wholescale Internet blackout.Footnote 5 The presence of a “kill switch” in some countries means that the state can easily disrupt telecommunications by creating a network blackout, a crude though often effective form of digital repression. It is more technically difficult, for example, to restrict access to a specific platform such as WhatsApp or Twitter, or to block access for a specific individual or group, especially if targeted individuals have their own technological expertise to develop effective workarounds (i.e., virtual private networks, for example). The target and form of digital repression is therefore influenced by the state’s availability and nature of tactical expertise.

2.3 Responsive Repressive Agents

Once a threat has been identified and a repressive strategy has been chosen, governments rely on repressive agents to implement that strategy. In general, the leader himself/herself is decidedly not the agent of repression. Instead, the state relies on a repressive apparatus. Unpacking the state into a principal (leader) and an agent (the security apparatus), as much of the literature on repression does, is helpful for demonstrating that organizational capacity and power are necessary dimensions of the state’s ability to repress. This ability corresponds to the level of centralization, the degree of organization, and the level of loyalty of the repressive agents. The agents of repression are often confined within a set group of organizations that vary by regime and regime type, such as the police, military, presidential security, etc. On rare occasions, state repression can be outsourced to agents not directly under the command of the state, for example, pro-government militias, vigilante groups, or private military contractors. The outsourcing of repression further complicates the issue of ensuring compliance from repressive agents. The state must have the ability to develop these organizations as loyal, responsive agents endowed with the expertise to implement the relevant repressive tactic.

Some forms of digital repression may require fewer repressive agents, simplifying principal-agent issues for repressive states. For example, digital repression might be carried out by a few technical experts within a government agency, or by an automated algorithm. One intuitive possibility is that requiring fewer agents to carry out a repressive action is less costly because of lower coordination costs and gains in efficiency. In the past, mass surveillance required an extensive network of informers. For example, in Poland in 1981, at the height of the Sluzba Bezpieczenstwa’s (Security Service) work to undermine the Solidarity movement, there were an estimated 84,000 informers (Day, Reference Day2011). New technologies produce the same level of surveillance (or greater) from the work of far fewer people. However, while fewer agents may be easier to coordinate, failure or defection by one among only a few repressive agents may be more costly in comparison to failure by one among thousands.

Online communication and access to digital space further requires a telecommunication company or Internet provider which may be outside of the state’s direct control. Though governments often have ownership stakes in these companies, which are seen as a public utility, the companies themselves remain independent actors. The level or ease of control that the state exhibits over the ICT sector varies, thereby shaping how easily the state can compel the sector to engage in repressive behaviors, such as monitoring usage or controlling access. For certain forms of digital repression, governments require greater capacity to compel specific actions on the part of these actors (such as shutting down the Internet, limiting access to specific platforms, limiting broadband access, etc.). The power to compel these actions is determined by government involvement in the sector and by market characteristics (industry structure and the number of actors), as well as existing legal protections – for example, regulations determining whether or when Internet service providers are required to turn over data to the state. In Europe, the General Data Protection Regulation, though aimed primarily at private actors, gives greater control to users over their individual data, and therefore makes it more difficult for governments to obtain access to personal, individual user data. If firms cannot collect it, they cannot be compelled to provide it to governments. In these ways, ICTs have the potential to simultaneously simplify and complicate the state’s relationship to its repressive agents, making it difficult to anticipate how ICTs will change the costs of repression in this regard.

2.4 Infrastructure of Repression

The capacity to apply repressive pressure in response to an identified threat requires what might be called an infrastructure of repression. This infrastructure should be thought of as the physical, geographic, or network characteristics that make it more or less costly (in terms of effort and resources) to engage in repression. At its most basic, repression infrastructure refers to sites of repression, such as prisons and detention facilities. It also refers to the physical environment in which repressive tactics are executed, which include the man-made and natural terrain that shapes the costs of repression (Ortiz, Reference Ortiz2007). In civil war literature, many have argued that the existence of a paved road network reduces the government costs of repressing a threat because government vehicles and soldiers can more easily access their targets (Buhaug & Rød, Reference Buhaug and Rød2006). This result echoes James Scott’s discussion of the rebuilding of Paris by Hausmann, which had the explicit goal of constructing a gridded road that government troops could use to more easily reach any part of the city to prevent or put down riots or protests in the aftermath of the French Revolution (Scott, Reference Scott1998).

The concept of a repressive infrastructure has an intuitive analogue in the digital repressive space due to the physicality of telecommunications. The technologies that facilitate communication and the diffusion and exchange of information require physical infrastructures – the cellular towers, the fiber-optic cables, the data centers, and interconnection exchangesFootnote 6 – that are the building blocks of the networks of digital and cellular communication.

Scholars have begun to use the characteristics of a country’s Internet technology network of autonomous systems (ASs) and the number of “points of control” to rank and characterize digital infrastructure in terms of the level of control governments can exert over citizen access to telecommunications networks and the data flowing across them (Douzet et al., Reference Douzet, Pétiniaud, Salamatian, Limonier, Salamatian and Alchus2020). Autonomous systems route traffic to and from individual devices to the broader Internet, which in turn is a collection of other ASs. The AS is, therefore, the primary target of regulation, monitoring, and interference by the state. Because most ASs are part of a larger network of systems, the vast majority of Internet traffic flows through a relatively small number of ASs within a country (often between three and thirty).Footnote 7 The minimum set of ASs required to connect 90 percent of the IP addresses in a country are called “points of control.” The more points of control there are in a country, the more costly it is to regulate or restrict digital communication (both in terms of skills and equipment).

Roberts et al. (Reference Roberts, Larochelle, Faris and Palfrey2011) have mapped two characteristics of in-country networks: the number of IP addresses (a proxy for individual users) per point of control and the level of complexity of the network within a country (the average number of ASs a user has to go through to connect to the Internet). Countries with more centralized systems and fewer points of control are places in which governments can much more easily exert control over access to the Internet for large portions of the population, and over the data that travel across the network. For example, as of 2011, the Islamic Republic of Iran had only one single point of control, with over four million IP addresses and a low network complexity score, which ensured that the state could easily control the entire Internet. According to Roberts, “in Iran, shutting down each network takes only a handful of phone calls” (Roberts et al., Reference Roberts, Larochelle, Faris and Palfrey2011, p. 11). As a result, such systems may require less expertise, less time, and less equipment to obtain and collect data, monitor users, or limit access. The greater the level of control over the infrastructure a state commands, the lower the costs to engage in digital repression.Footnote 8

In addition to the network characteristics of the Internet within a country, the infrastructure for digital repression is also characterized by how the majority of individuals communicate and access the Internet. Smart cellular phones are by far the most common devices used to access the Internet, in addition to facilitating voice and text communication. They provide an additional point in the digital infrastructure where states can exert control. For example, states may impose regulations requiring proof of identification in order to obtain a cell phone and sim card. By doing so, they are able to collect large amounts of data about who owns which devices, and thereby monitor individual communications and data (including locational data).

3 New Thoughts on Digital State Repression and Cyber Peace

States repress when the benefits of repression outweigh its costs. But when states repress using digital tools, how does this calculus change? How do digital forms of repression coexist with, or substitute for traditional forms of repression? And how does the combination of traditional and digital forms of repression affect the goal of cyber peace?

These are some of the questions we need to address in order to tackle the complex interactions among domestic state repression, digital technologies, and cyber peace. This chapter does not provide comprehensive answers, but it begins to unpack these interactions. In particular, our contribution is twofold. First, we break down repression into four constituent components, facilitating a conceptualization of repressive actions that cuts across the traditional/digital divide. This framework provides a useful workhorse for advancing research on the empirical patterns of repression. Second, we use this mapping to begin to explore the complex ways in which digital repression can impact each of the four components.

The value of our mapping exercise for scholars and practitioners in the field of cyber peace and cybersecurity emerges most poignantly in the reflections we offer about the tradeoffs between domestic and international security. For example, an Internet architecture that has a single point of control allows for governments to easily control access to the Internet and monitor data traveling over the network, but it also presents a vulnerability to foreign actors who only need to obtain control of, or infiltrate that point of control in order to gain access to domestic networks. This was in fact the case with Iran which, as noted earlier, had a single point of control until 2011. However, in recognition of the potential vulnerabilities to foreign intrusions that this created, Iran has since sought to add complexity to its digital infrastructure (Salamatian et al., Reference Salamatian, Douzet, Limonier and Salamatian2019). But, as a result, it also had to acquire greater expertise to manage this complexity, developing a broader range of tools to monitor users and control access (Kottasová and Mazloumsaki, Reference Kottasová and Mazloumsaki2019). Another issue concerns strategic interdependencies: States may need to rely on international collaborations to carry out repression within their own borders. This problem is particularly acute given the fact that servers are often housed in data centers outside the country in which most of their users reside.

Our contribution also suggests that some of the core insights in the literature on repression need reconsideration. For example, the literature on repression suggests that while all regime types repress, democracies repress less than autocracies (Davenport, Reference Davenport2007). However, this may not be true in the case of digital repression. Given the importance of the audience costs that we tend to associate with democratic regimes, we might expect democracies to invest and engage more in forms of repression that are more difficult to detect and observe. Perhaps, more interestingly, the existing literature suggests that democracies and autocracies differ with respect to the way they use information, and such differences expose them to different threats (Farrell & Schneier, Reference Farrell and Schneier2018). This difference may shape the cost–benefit analysis of engaging in certain forms of digital or traditional repression in distinct, regime-specific ways.

Moreover, the repression literature further suggests that under certain conditions state repression may increase rather than eliminate dissent. The dissent–repression nexus may require reexamination in light of how ICTs are reshaping repression. The addition of a new menu of repressive tactics that can be used in conjunction with, or in place of, traditional forms of repression may lead the state to more effectively mitigate or eliminate threats in ways that make them less likely to resurface or produce backlash. This is in part because of the addition of more covert forms of repression that might be less observable and generate fewer grievances down the line.

Finally, the literature suggests that repression requires high levels of state capacity. However, when states repress through computers, and not police and tanks, repression may rely on sectors and skills that we do not currently measure or think of as relevant dimensions of state capacity. In particular, taking a more granular, multidimensional approach to state capacity, with particular attention to the specific capacity to repress, may shed new light on the relationship between generalized state capacity for repression and state capacity for digital repression.

These observations also yield a distinct, methodological question: If digital repression makes preemptive repression more effective, how can we continue to effectively measure repression since we will have many more unobservable cases in which repression preempted the emergence of an observable threat? Although we do not venture to answer this question, we hope that our chapter offers a starting point for a comprehensive analysis of repression in its traditional as well as digital forms.

The ability of states to violate the political and civil liberties of their populations through digital technologies is a direct threat to cyber peace. While often overlooked in our more internationalized discussion of cyber warfare, how states use and misuse digital technologies to monitor and control their populations is a subject that requires much more attention both because it can shape and be shaped by internationalized cyber warfare, and also because it is an important empirical and normative concern in and of itself.