Book contents

- American Survivors

- American Survivors

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Figures

- Abbreviations

- Notes on the Text

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 Cities of Immigrants

- 2 Remembering the Nuclear Holocaust

- 3 Reconnecting Families

- 4 War and Work Across the Pacific

- 5 Finding Survivorhood

- 6 Endlessness of Radiation Illness

- Epilogue

- Notes

- Glossary

- Select Bibliography

- Index

- References

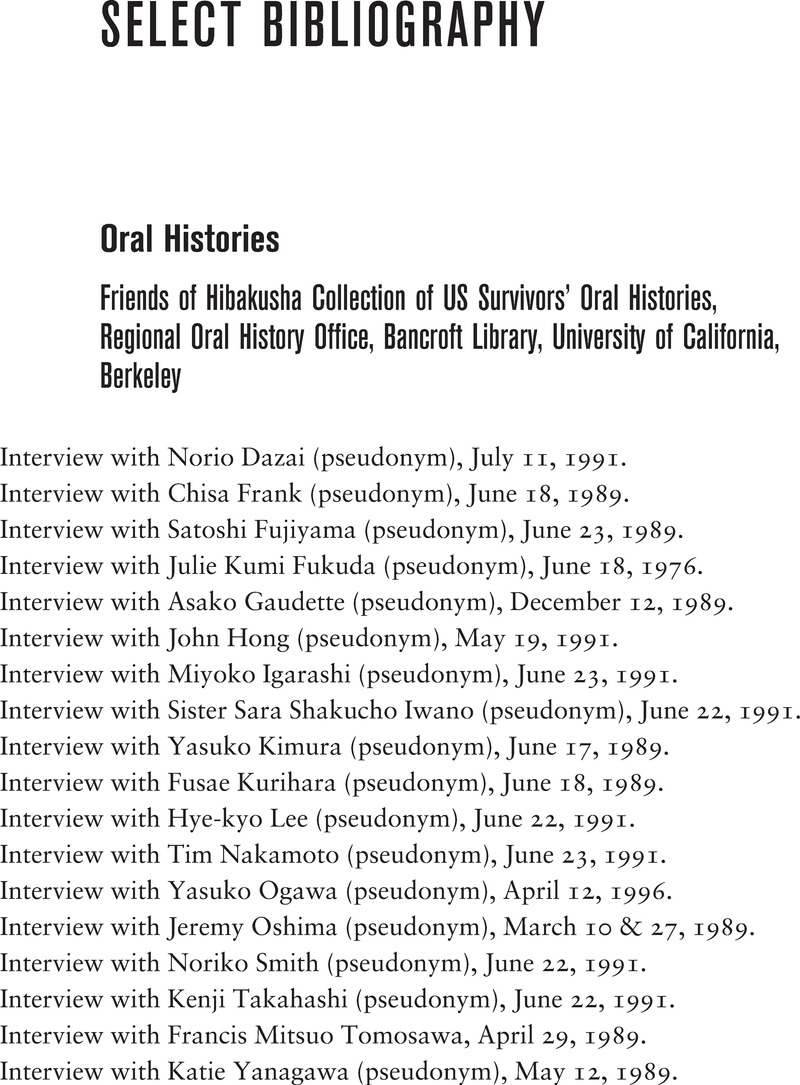

Select Bibliography

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 May 2021

- American Survivors

- American Survivors

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Figures

- Abbreviations

- Notes on the Text

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 Cities of Immigrants

- 2 Remembering the Nuclear Holocaust

- 3 Reconnecting Families

- 4 War and Work Across the Pacific

- 5 Finding Survivorhood

- 6 Endlessness of Radiation Illness

- Epilogue

- Notes

- Glossary

- Select Bibliography

- Index

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- American SurvivorsTrans-Pacific Memories of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, pp. 366 - 380Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2021