Book contents

Bibliography

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 15 May 2020

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

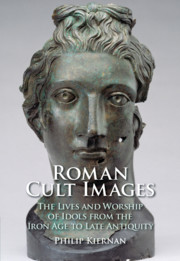

- Roman Cult ImagesThe Lives and Worship of Idols from the Iron Age to Late Antiquity, pp. 321 - 346Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2020