Book contents

- The Cambridge Handbook of the Philosophy of Language

- Cambridge Handbooks in Language and Linguistics

- The Cambridge Handbook of the Philosophy of Language

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Figures

- Tables

- Contributors

- Preface

- 1 Philosophy of Language: Definitions, Disciplines, and Approaches

- Part I The Past, Present, and Future of Philosophy of Language

- Part II Some Foundational Issues

- Part III From Truth to Vagueness

- Part IV Issues in Semantics and Pragmatics

- Part V Philosophical Implications and Linguistic Theories

- Part VI Some Extensions

- References

- Index

- References

References

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 12 November 2021

- The Cambridge Handbook of the Philosophy of Language

- Cambridge Handbooks in Language and Linguistics

- The Cambridge Handbook of the Philosophy of Language

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Figures

- Tables

- Contributors

- Preface

- 1 Philosophy of Language: Definitions, Disciplines, and Approaches

- Part I The Past, Present, and Future of Philosophy of Language

- Part II Some Foundational Issues

- Part III From Truth to Vagueness

- Part IV Issues in Semantics and Pragmatics

- Part V Philosophical Implications and Linguistic Theories

- Part VI Some Extensions

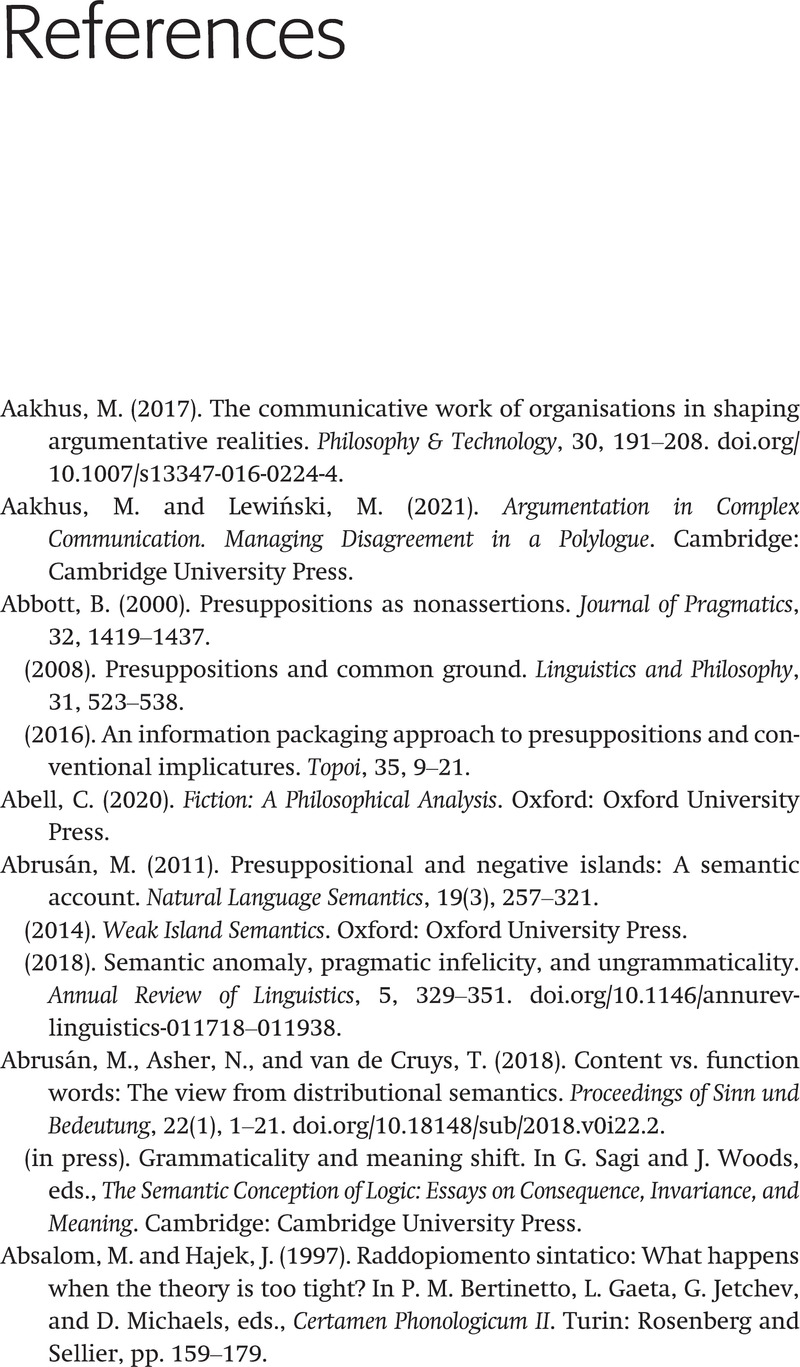

- References

- Index

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- The Cambridge Handbook of the Philosophy of Language , pp. 692 - 809Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2021