In the debate around Shakespeare and 9/11, the question of Shakespeare’s political uses tends to be addressed only in the most oblique of ways. As Matthew Biberman, the editor of Shakespeare Yearbook’s special issue on the theme, notes, criticism typically retreats into a looser discussion of ‘the role that canonical texts can play in the development of ethical, philosophical and civic frameworks’.Footnote 2 The one exception is the discussion generated by Henry V. Critics have noted the way in which Henry V is marshalled to support the language of contemporary militarism, with Diana E. Henderson and others citing the controversial manner in which the play was ‘issued to US soldiers … and repeatedly invoked in speeches … and on websites supporting military actions’.Footnote 3 In complementary work, critics have noted the popular comparisons between Henry V and figures such as George W. Bush, Tony Blair and Tim Collins.Footnote 4 But what tends to be dramatized most fully in these encounters is the gulf between academia and popular usages of Shakespeare’s text. Critical discussion is directed towards demonstrating the inappropriateness of contemporary parallels, and users are encouraged to engage more subtly with the play (undoubtedly good advice for succeeding British and American administrations, but unlikely to be heeded).Footnote 5 Hence, while such commentary implicitly acknowledges that Henry V has a special resonance inside the discourses of Afghanistan and Iraq, the precise ways in which Henry V signifies in the here-and-now remains to be fully considered.

Part of the difficulty is the scant attention afforded in such work to imaginative/creative productions of Henry V. As Matthew Woodcock notes, ‘the twenty-first century stage has gone much further than academic criticism in drawing comparisons between Henry’s campaign and the Iraq War’.Footnote 6 In fact, the period since 9/11 has seen unprecedented numbers of Henry V productions, as well as the first major film in almost thirty years. Thea Sharrock’s Henry V (2012), starring Tom Hiddleston, was crafted to form the high point of the cultural Olympiad, internationally co-produced (the BBC joined forces with Neal Street Productions, NBC Universal and WNET Thirteen) and distributed to great acclaim.Footnote 7 Like most of the theatrical productions of Henry V since 2001, the film draws on discursive strategies shaped by the ‘War on Terror’, the now-defunct term which signifies the international military campaign waged in the aftermath of 9/11, including the Iraq War and the War in Afghanistan.Footnote 8 Sharrock’s film – the first Henry V to be directed by a woman – crystallizes a trend initiated by a number of productions which, in the wake of the successful National Theatre production of Henry V directed by Nicholas Hytner in 2003, refract the Iraq and Afghanistan conflicts in the action on stage.Footnote 9

In reconceiving of Shakespeare’s history in a way which is inseparable from contemporary understandings of conflict, Sharrock follows in the footsteps of Laurence Olivier and Kenneth Branagh and their now-canonical film adaptations of the play.Footnote 10 In common with these directors, Sharrock also offers a reading of Henry V in part determined by the contemporary representational landscape. Recent work in film studies has highlighted ‘the way in which … depictions of war have shifted since the mid-1980s’, signalling, in particular, a move away from the anti-war Vietnam films.Footnote 11 As exemplary of this development, critics highlight a group of late 20th- and early 21st-century World War II films such as Saving Private Ryan (dir. Steven Spielberg, 1998), which, revisionist and recuperative in orientation, illuminates the rise of what Andrew J. Bacevich has identified as a ‘New American Militarism’.Footnote 12 Spotlighting a ‘tendency to see military power as the truest measure of national greatness’, Bacevich describes a romanticized and nostalgic conception of wars, armies and soldiers that ‘pervade[s] the American consciousness’ and ‘ultimately pervert[s] US [foreign] policy’.Footnote 13 Linked to this cultural phenomenon, but distinctive in style and approach, is a more recent and controversial series of films based on the Iraq War experience. Films such as Generation Kill (dir. Susanna White and Simon Callas Jones, 2008), Redacted (dir. Brian de Palma, 2007) and In the Valley of Elah (dir. Paul Haggis, 2007) are often edgy, uncomfortable and interrogative in their attitudes towards the War on Terror.Footnote 14 Guy Westwell notes that the Iraq War films generally proved unpopular, failing ‘to find an audience’, and the few that did, such as the Oscar-winning The Hurt Locker (dir. Kathryn Bigelow, 2008) and American Sniper (dir. Clint Eastwood, 2014), were notably much less political – less critical – in orientation.Footnote 15 Typically, the vision of war in the commercially successful Iraq War films embeds a human experience divorced from larger questions of political accountability. Sharrock’s Henry V begs comparison with this new wave of war films in that it retains a heroic emphasis while largely avoiding engagement with the politics of war – the ‘cause’ (4.1.133), as Shakespeare’s play has it – and it executes this dual manoeuvre through a narrow focus on the bodily experience of a small group of soldiers.Footnote 16

This focus on a trajectory of suffering allows Sharrock to negotiate in a unique way ‘the essential doubleness’ that critics from Norman Rabkin to Stephen Greenblatt have identified around Shakespeare’s Henry V.Footnote 17 In particular, the film invokes the associations around post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), which Anthony Oliver Scott ‘argues … is the defining feature’ of the Iraq War films, to reconcile and explain antithetically opposed images of Henry while connecting with the anxieties of present-day audiences.Footnote 18 Situated inside a new – post 9/11 – Shakespearian aesthetic which prioritizes the solider as spectacle, Sharrock’s film, energized by a decade of theatrical innovation, realizes a Henry V very different in complexion, scale and significance from that of her predecessors – hence, the unfamiliar effects of a film which cuts scenes and soliloquies traditionally regarded as essential, reintroduces episodes conventionally bypassed, invests in daring interpolations and capitalizes on a performative style that overturns received interpretation. Caught in a net of its Olympic contexts, the film has thus far been seen only inside its commemorative paradigms.Footnote 19 In arguing that Sharrock’s production manifests a fresh conceptual template for Shakespeare’s history, this article suggests that the contemporary applications of Henry V move beyond the simplistic parallels which have so exercised and animated critical discussion. By prioritizing the fields of debate that surround Henry V, it identifies, for the first time, the extent to which the War on Terror has transformed the meanings of Shakespeare’s greatest history.

A Modern Obituary

In Sharrock’s production, a radical take on the narrative is encapsulated in the scenes of Henry’s funeral which open and close the film. Merging the play’s prologue and epilogue, the film enables us to hear the former (the invocation to the muse) but to see the events associated with the latter (the death of the protagonist). The symbolism of the opening shot – a dirty-faced child plucking a wild flower (its shape evokes the epilogue’s ‘star of England’ (6)) and running past the Boar’s Head (the scene of revelries now eclipsed) – speaks of loss and impermanence. Dark painterly effects, tenebrous lighting and alienating medieval architecture match this mood and confirm the anti-heritage landscape characteristic of many recent Renaissance appropriations. Although the end reveals that he has been in attendance all along (he is finally revealed as Shakespeare’s ‘Boy’ offering a retrospective viewpoint), the Chorus is apprehended at this point only via a gravelly, sombre voiceover. In keeping with the muted emotional contours – and despite the verse’s aspiration towards elevation and an upward movement – the slow delivery and downward intonation of the prologue’s lines – ‘O for a muse of fire, that would ascend / The brightest heaven of invention’ (1–2) – strikes a defeatist note, with viewers being invited to imagine great possibilities (not least, ideas of animation and resurrection) in the context of brute mortality (the death/funeral) and communal devastation (the assembled mourners). Bolstering the emotional contours is the score – a doleful Celtic strain characterized by strings and minor chords – that, in contrast to the rousing epic film music of Branagh’s and Olivier’s adaptations, lends the scene a subdued melancholy and an elegiac air.

For Lindsey Scott, the summoning of different stages in the story of Henry V reminds us of ‘how Shakespeare’s audiences would have been aware of Henry’s short reign from the preceding performances of the Henry VI plays’.Footnote 20 But the crane-shot of the laid-out corpse covered by a heavy flag invokes 21st-century iconography of soldiers’ bodies being brought home from conflict; contrary to the historical record, the effect is to suggest the King as casualty of the war in France.Footnote 21 This is confirmed in the voiceover’s identification of the corpse as ‘warlike Harry’ (Prologue, 5), establishing the funeral under way as that of a military combatant. (A choreographed glimpse of the guard of honour stepping forwards reinforces the soldierly associations.) Pointed up in the scene, then, is what Andrew Hill terms ‘the hard Real of the body-corpse … the material presence of combat, which … constitutes the incontrovertible detritus of war’.Footnote 22 Like contemporary soldiers William James (The Hurt Locker) and Chris Kyle (American Sniper), Henry, from the start, is limned in terms of a fatal trajectory. By filtering the narrative through the depressive events described by the Chorus at the close, Sharrock’s Henry V not only prepares an audience for what is to come but also begins the process of elaborating the hero in terms of victimhood. Long before the English army lands on French soil, mourning infuses the endeavour, with viewers recognizing Henry as a ‘dead man walking’. The perspective is one that the ensuing narrative never moves beyond, not least because the continuing voiceover keeps us connected to the idea and import of the funeral in what is – by a large margin – the most extended use of the Chorus on screen.Footnote 23

More broadly, the mutedly retrospective method functions to downplay the triumphant associations of what Crystal Bartolovich describes as ‘the most overtly “nationalistic” and Anglophilic text in the Shakespearian canon’.Footnote 24 The demythologizing tendency is specifically realized in the opening’s reference to Agincourt as a traumatic memory. At the Chorus’s lines, ‘the very casques / That did affright the air at Agincourt’ (Prologue, 13–14), overlaid sounds of the clash of swords, men’s cries and horses’ screams are heard. These combine with a close-up on Exeter, the source of the experience, who blanches, closing his eyes at the inadvertent recollection. This eruption of the past into the film’s present looks forward to similar episodes involving psychologically afflicted soldiers. Henry V, as Jonathan Baldo notes, is a play deeply engaged in the ‘consolidation of the collective memory’, but, in Sharrock’s adaptation, remembering is, first and foremost, a traumatic endeavour.Footnote 25

The moment prefigures the fantasy of England’s remembering celebrated in Henry’s St Crispian speech but models instead a contemporary concern with the place of the personal story inside the commemoration of national conflict. Henry’s passing is figured simultaneously as a collective loss (the death that makes England and France bleed, as the epilogue has it) and as a private domestic tragedy. The latter is bolstered by the camera’s focus on the loving looks bestowed by Katherine on the corpse. Ideas of personal affliction are further emphasized when the corpse is unveiled and a giddy 180° camera pan mimics Katherine’s grieving perspective. Via self-conscious camera work, the production constructs the Henry–Katherine relationship as a love match, pre-emptively diffusing the later difficulties of staging Act 5, Scene 1. Re-envisioning a play ‘famous for the relative absence of women’, the interpolation characteristically amplifies the significance of Katherine (Mélanie Thierry), signalling a felt responsiveness to a world of heroism previously construed – by Olivier, by Branagh and by Shakespeare – almost wholly in masculine terms.Footnote 26 The sense that this is a tragedy belonging in the first instance to Henry’s nuclear family is strengthened by the appearance here of a character only mentioned in the epilogue – ‘Henry the Sixth’ – for, behind the spectating widow, a waiting-woman is seen carrying a vulnerable new-born in ‘infant bands’ (Epilogue, 9). As in Iraq films such as The Hurt Locker, Henry here is realized not in terms of the larger political landscape but at the level of the career path characterizing ‘the individual soldier’.Footnote 27 The method is exemplified as the camera zooms into the exposed corpse and pauses on a close-up of Tom Hiddleston’s fine (if fixed and pallid) features. At this moment, the music climaxes and the production title freezes, with title, theme and subject succinctly being brought into union. Made apparent via his lover’s gaze, but discovered simultaneously in terms of a soldier’s funeral, Henry – and his march towards death – is cemented as subject, object and theme. The effect is to substitute the customary Henrician trajectory of boyhood to manhood with a single focus on manhood cut off in its prime. That generational movement so beloved by adapters of the play is replaced by an arc that begins with the protagonist’s death, goes on to his war and circles back to the flag-covered corpse (we return to the same funeral at the end). Bracketing the proceedings thus, Sharrock telescopes the dramatization of warring nations into a modern obituary.

The Militarized, Vulnerable Body

The business of Act 1 proper is jump-started by a match-cut which shifts the audience from a close-up of the exposed corpse to a close-up of Henry alive. The shot which links the two views of Henry – that of eyes being jolted open – implies a Lazarus-like resurrection, self-consciously recalling both the ways in which film is the medium that reanimates Shakespeare’s play and the revivifying powers, as described by the Chorus, of the audience’s imagination. Moving from death to life, it is appropriate that the first shots of Henry privilege physicality, and, as the scene plays over the dialogue between Canterbury and Ely, an extended sequence shows Hiddleston – minus the crown – astride a galloping white horse.Footnote 28 As Canterbury and Ely discuss his transformation, Henry is realized leaping from his horse and rushing into the palace, stripping off clothes and, as he runs, snatching up the crown.Footnote 29 The stress on action contrasts with the earlier stillness of the corpse, while simultaneously – in the words of Yvonne Tasker – providing ‘a narrative justification for … physical display’.Footnote 30 Sharrock’s Henry V is seductively oriented, with the pleasures of Hiddleston’s gym-honed body being played up throughout.Footnote 31 Even when Henry is in armour, the viewer’s eye is invited to dwell on the eroticized body because the battle attire is so precisely – unfeasibly – tight-fitting. The designer explains that Hiddleston’s armour was ‘made … out of rubber, and he was sewn into things … so he could move and look sexy’.Footnote 32 For Sharrock, there was an intimate connection between Hiddleston’s physique and the production’s ‘feel’: ‘I wanted him to have a look that was … [a]ttractive’, she notes. ‘He’s an amazing, beautiful man. It seems crazy to [give him] a bowl haircut or put him in a pair of tights.’Footnote 33

If Sharrock here marks her distance from the traditional stage and screen image of Henry V, the distinction is disingenuous. In fact, Sharrock’s sense of Henry’s appearance is perfectly aligned with a recent trend in theatre and cinema which has been to highlight – to ‘sex up’ – the militarism of Shakespeare’s male roles. Thus, Coriolanus, the 2012 film directed by Ralph Fiennes, Othello, the 2013 National Theatre production directed by Nicholas Hytner, and Othello, directed by Iqbal Khan for the RSC in 2015, prioritized conflict-zone settings, relying, variously, on the military training undertaken by the casts and such identifiers as hard bodies, replica guns, flak jackets and desert fatigues.Footnote 34 In these instances, costuming, in particular, intimately equates the sexuality of the Shakespearian hero with his military identity, bringing to mind the romanticized construction of militarism in the contemporary war film. Unlike the French (who are dressed to appear ‘shiny and … mannered’), in Sharrock’s film the English mostly wear leather, which costume designer Annie Symons describes as giving the actors ‘sexuality and a warrior-likeness’.Footnote 35 Caught up in this reification are the intertexts of Hiddleston’s earlier parts in Hollywood films such as Thor (dir. Kenneth Branagh, 2011) and Avengers Assemble (dir. Joss Whedon, 2013).Footnote 36 As Loki, brother to Thor, Hiddleston established himself as an ambiguated intergalactic warrior, while his role as Captain Nicholls in War Horse (dir. Steven Spielberg, 2011) suggests most strongly the identification of the Shakespearian type as a sexualized military protagonist. In Sharrock’s film, the interpolated Agincourt scenes show Henry fighting aggressively and stress how an audience’s gaze is directed towards a moving, spectacular property. Minus both horse and crown (the latter shoved dismissively away as battle commences), Henry functions as a summation of innate athleticism and soldierly accomplishment that collapses boundaries of rank and class. The notion of the contemporary soldier is most stridently enunciated in scenes where, face muddied and shadowed, Henry’s appearance recalls the familiar contours of the War on Terror forces; a medieval setting notwithstanding, the visual complexions suggest camouflage, besmirching, nocturnal encounters and a particular enunciation of 21st-century warfare. The so-called ‘charred face’ (which supersedes the mud-bespattered mise-en-scène of Branagh’s adaptation) is the signature of the authenticated battle experience.Footnote 37

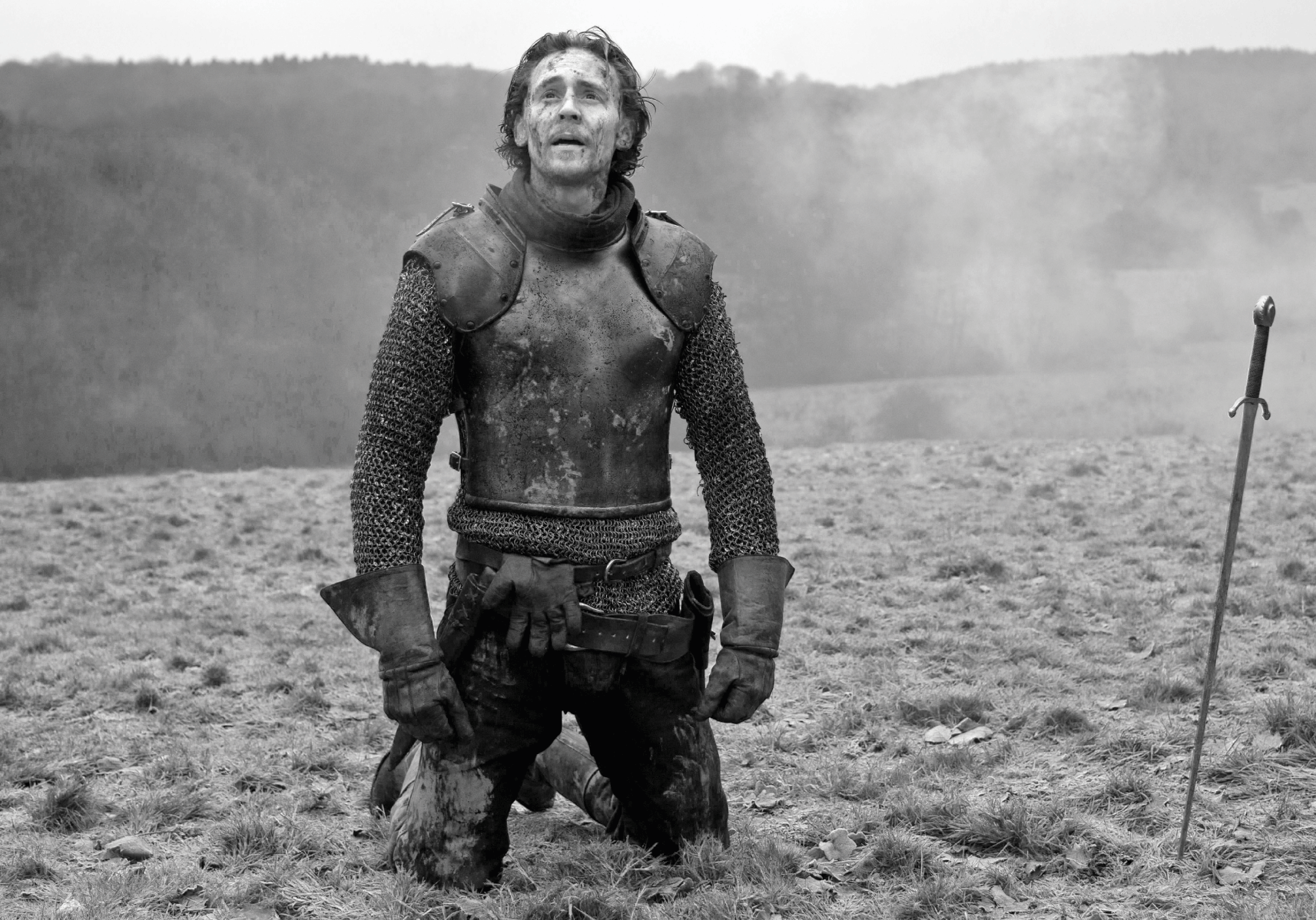

This fine adjustment in visual detailing sits well with the filmic motif of the victim-soldier. Echoing Iraq War films which delineate the vulnerability of American troops in Baghdad, Henry’s campaign in France is marked by a concentration on the beleaguered situation of the English. Characterized by inhospitable wintry terrain and formidable stronghold walls, France is alien territory and the war effort a depressed undertaking – coughing, exhausted men, some carrying compatriots, are the downcast corollaries for what is conjured as a wholly dispirited enterprise. At Harfleur, fearful and defensive camera work establishes the perspective as that of the ‘noble English’ (3.1.17) (Figure 1). Because screams, images of affliction and shots of burning oil being poured from the battlements are associated with the English experience, the dynamic of the historical siege is reversed, and Henry’s army is limned as the imperilled constituency. Eschewing the Union Jacks which so often accompany theatrical productions, Sharrock’s Henry V privileges a period-suitable tattered and dirty flag of St George which, fluttering in sorry fashion, emblematizes both the state of Henry’s army and its distance from patriotic imperatives. The flag finds a psychic correlative in the ways in which Henry’s soldiers, soon after arriving in France, begin to exhibit the ‘thousand-yard stare’, perhaps the most cinematically recognizable aspect of post-traumatic stress sufferers. Tracing the history of PTSD, Martin Barker notes that discourses around the condition serve as a point of consensus between all sides in American politics, and facilitate a reading of the US military as victims rather than perpetrators.Footnote 38 In Sharrock’s film, the representation of the pervasiveness of PTSD suggests that the condition is one of soldiering’s inexorable effects. The theme is expressed personally at Agincourt via the image of a foetally positioned Pistol who is paralysed and horrified by what he is witnessing – PTSD is triggered by his exposure to atrocity. Discovered in the next scene as crying, shaking and rocking his head, Pistol registers in his behaviour the disorder’s pre-eminent symptoms.Footnote 39 Interestingly, Pistol’s later lines are cut; PTSD, it is suggested, has become his defining story.

Notwithstanding the subtle colour distinction between the armies (‘dark congealed bloods for England and beautiful blues, whites and golds for France’), Agincourt is characterized by an overwhelming sense of visceral brutality.Footnote 40 Alternately accelerated and slow-motion representations of the battle make prominent the various acts of impaling and skewering in which both forces participate.Footnote 41 Thanks to a quasi-documentary style, realist details and hand-held filming techniques, a viewer is quickly immersed in battle scenes which invite comparison with Peter Babakitis’s lesser-known 2004 cinematic version of the play, Henry V. Sarah Hatchuel notes that, in this adaptation, the ‘cinematography … seems heavily influenced by media footage provided by … commentators during the 2003 British and American invasion of Iraq’.Footnote 42 In the Sharrock adaptation, the interpolated injunction from Henry (‘Advance the army thirty paces – now!’) and the scene which sees Essex wait for the perfect moment for the arrows to be loosed (‘Steady lads!’) simultaneously situate military success while allowing for the suspense so integral to contemporary depictions of warfare.Footnote 43 As befits this mode of representation, instead of the heavy classical orchestration of Branagh’s and Olivier’s scores, the soundtrack is merged with the noise of the combatants’ pain, anguish and blows in a critical cacophony of violence. Key military moments are backgrounded by a wall of smoke that rises from behind the combatants, and a sense of chaos dominates. When Henry pronounces, ‘I know not if the day be ours or no’ (4.7.82), the disorientation is absolutely convincing, for it is one that is filtered through a distinctly contemporaneous aesthetic.

Inside this contemporary understanding of warfare sits Sharrock’s daring re-envisioning of the play’s great set-speeches. If, as Linda K. Schubert argues, ‘Branagh’s choices … [were] deliberately the opposite of those informing Olivier’s movie’, then Sharrock, in turn, sets herself against Branagh by avoiding, in her words, ‘the huge rhetorical thing’.Footnote 44 Playing down excess and working in conversational ways, her Henry V utilizes the rhetorical underplay characteristic of the Iraq War film to make its set-speeches the most understatedly delivered in the screen record. ‘Once more unto the breach’ (3.1.1) is realized instinctively, as evolving spontaneously from the contexts in which the protagonist finds himself, and Henry himself is represented on his knees (debris falling all around). In the ‘Feast of Crispian’ (4.3.40) address, low-key tones predominate, and most of the speech proceeds without scoring; the suggestion of a private farewell is assisted by emotive sighs and weighty pauses.Footnote 45 Recognized in both is an uneasiness with the declamatory mode – what Nicholas Hytner, reflecting on his own stagecraft, has termed a public ‘mistrust of … rhetoric’.Footnote 46 Sharrock’s Henry V is sensitive to the evisceration of rhetoric in the public sphere and, by dampening its force, endeavours to ensure that Henry is never figured in directly political terms.

Crucial to the construction is Henry’s participation in a shared experience of vulnerability. Hiddleston, as one reviewer notes, is a ‘cerebral actor’, and nonverbals – a broken delivery and pained facial expressions – make for a revisionist reading that places emphasis on the King’s own fears.Footnote 47 Given that the wearisome accoutrements of leadership are already written through Hiddleston’s body, the soliloquy on the ‘hard condition’ (4.1.227–81) of kingship (traditionally regarded as ‘central to the complex modern Henry’) is cut.Footnote 48 Instead of lonely communion, the emphasis is on Henry’s connection with a small group of individualized soldiers. Hence, the cropped camerawork of ‘Once more unto the breach’ underlines the closeness of the encounter, and Shakespearian plurals are suitably contracted – the general ‘yeomen’ (3.1.25) become a solitary ‘yeoman’. Such decisions make sense given the nature of contemporary warfare – no longer fought by large armies but by small detachments.Footnote 49 As in the Iraq films in which, as Martin Barker notes, ‘soldiers are shown bonding with each other, giving this as their first loyalty’, it is the values of the unit (the group whose interests Henry represents and defends) that are accorded the greatest importance.Footnote 50 In the St Crispian speech, this change of emphasis is encapsulated in the climactic delivery of the expression, ‘band of brothers’ (4.3.60), and in the registration of the hero’s sentimental mood in the tears of his listening soldiers. Accordingly, a break with performance tradition accents the inclusive ‘us’ (4.3.67), in contradistinction to the exclusive ‘not’ – the situation of ‘gentlemen’ (4.3.64) who do not participate – so that the significance of the saint’s day becomes about affirming male relations.

More generally, Sharrock’s Henry V visualizes man-on-man relationships in a way that is unprecedented in the stage and film history of the play. During Henry’s night-time meetings, the ‘comfort … pluck[ed]’ (4.0.42) is granted physical exposition, as hands are shook, smiles exchanged, backs patted and hugs welcomed from a singularly tactile protagonist. Consonant with the stress on male bonding, the production omits the discovery of the traitors’ conspiracy, eschews mention of the Scottish rebellion (1.2.136–220) and cuts that ‘furious repudiation of difference’, the four captains’ scene.Footnote 51 The infamous question – ‘What ish my nation?’ (3.3.66) – becomes untenable in a production where relations between men take precedence over national affiliation. Distinctively, the development is given a racial inflection through the casting of the black actor Paterson Joseph as York. The mode of representation accords with the ‘colour-blind’ casting of most contemporary Henry V productions, but – complicating Jami Rogers’s view that, in The Hollow Crown, no ‘ethnic minority actors’ were cast in ‘major roles’ – York is a notable presence, with extensions deepening and stretching the part.Footnote 52 These, and the fact that York is consistently visualized, mean that Henry’s soldierly fraternity appears, as L. Monique Pittman has discussed, as a contemporary, multicultural phenomenon.Footnote 53 It is also possible to read York as enacting a symbolic role, not least in the light of Martin Barker’s observation that, in the Iraq War film, ‘special figures … [often] representatives of minorities … stand out … [to] embody a new kind of soldier: the hero-victim’.Footnote 54 York’s death is staged as the centre point of the Agincourt scenes, with Surrey’s death (4.6) extracted out so as not to blur the solitary focus. Caught in an off-guard moment while comforting the Boy, he is violently stabbed in the back, the reprehensibility of the French Constable’s actions brutally realized in York’s abject condition and lingering death. York’s blood-steeped torso contrasts with the draped and cleansed corpse of Henry at the start, stressing the former’s status as a symbolic victim of derelictions in military conduct.

The symbolism is carried forward in the film’s most important property – the talismanic flag stained with York’s blood and retained by the Boy as an arm-band. A memento mori not only of the wounded war body but also of the war crime, the flag makes manifest the film’s memorializing strategies. As relic, it newly locates the monarch’s predictive claims: in the scrap of material, it is the illegitimacy of York’s death that is ‘freshly remembered’ (4.3.55).

The Ideology of the Suffering Soldier

Director Nicholas Hytner has argued that, post-Iraq, any contemporary reworking of Act 1, Scene 2 (in which the justification for war is set out) is ‘far more interested in the ways our war leaders … take us to war than it is in the rights or wrongs of the cause’.Footnote 55 Sharrock’s production similarly prioritizes process. The church’s plan to go to war to avoid financial ruin (1.1.7–11, 79–81) is captured in close-up, and Henry’s cynicism around ecclesiastics is stressed via a delay in Hiddleston’s pentameter. Henry’s response to Canterbury’s unctuous greeting, ‘Sure we thank you’ (1.2.8), is ruptured to read, ‘Sure’, with a notable pause before the subsequent expression of thanks. The meaning is akin to the modern ‘whatever’, a signal that the protagonist recognizes as insincere the archbishop’s rhetorical persiflage.Footnote 56 The warning ‘take heed’ (1.2.21) is delivered formally as a righteous affront, and the question ‘May I with right and conscience make this claim?’ (1.2.96) is highlighted because transposed to the start of Henry’s address. Typically for this production, nonverbals continue as indices of meaning: the expressions that flash across Henry’s face and the restless tapping of his fingers suggest hesitation, a monarch unsure whether there really is a persuasive case for war.

At the same time, semi-circular blocking (mimicked by the claustrophobic circling of the camera around Henry) suggests the combined forces – ecclesiastical and political – ranged in opposition to Henry’s questioning, and in this regard it is noticeable that the production includes all of the nobles’ supportive assurances (1.2.122–31), along with a series of response shots that point up a shared encouragement.Footnote 57

The speech on the Salic law (1.2.37–95) is cut, its content transposed instead onto a scroll. The material surrogate is reminiscent of the National Theatre production (where Canterbury handed out ‘copies of an elaborately produced dossier … explain[ing] England’s right … to take military action’), but, of course, has its raison d’être in the Blair government’s ‘dodgy dossier’ (which fraudulently detailed Iraq’s ‘Weapons of Mass Destruction’).Footnote 58 Sharrock’s film extends the use of this property, as the scroll passes between king and nobles and is also substituted for the ‘paper’ later handed to the French King by Essex.Footnote 59 In this way, the narrative bypasses any exploration of the rationale for war, shifting attention instead onto texts that visibly circulate but are never revealed or interrogated. The effect is to keep ideas about the ‘cause’ circulating and to suggest that, throughout the narrative, it remains a matter of irresolution. Uncertainty around the ‘cause’ is given additional emphasis in Henry’s later discussions with Williams: the latter’s arguments are retained, while the former’s theological justifications are cut. Comments such as ‘That’s more than we know’ (4.1.128) echo moments in the Iraq War films in which discussion about the reasons for military presence are opened up only in order immediately to be closed down.

With the ‘cause’ displaced, endlessly deferred or never adequately addressed, it is Henry’s conduct in war on which an audience is obliged to focus. Here, as in the film adaptations A Midsummer Night’s Dream (dir. Adrian Noble, 1996) and Titus (dir. Julie Taymor, 1999), the interpretive lens of a child affords a vantage point from which Henry’s actions are scrutinized. Because the end of the film reveals the Boy to have the Chorus’s retrospective viewpoint, he is allowed a cross-narrative authority and an experiential – interpretive – knowledge. Although most of his lines (including the long speech at 3.2.29–54) are cut, the Boy consistently appears in the margins of the mise-en-scène: war and its attendant horrors are mediated through his gaze. Following the 2013 Michael Grandage production of Henry V, in which Boy and Chorus are similarly doubled, then, Sharrock positions the Boy/Chorus as a type of ‘embedded reporter’ imbued with authenticity.Footnote 60

The Boy’s function is exemplified in the Bardolph scenes. Unlike Branagh, who uses the episode ‘to emphasise the personal cost for Henry’, Sharrock directs the spotlight onto the implications of Bardolph’s offence.Footnote 61 As in Iraq War films, which are distinctive for including moments of culpable, even criminal, soldiering, an uncompromising reading of Bardolph as an example of aberrant soldierly behaviour is prepared for at Harfleur where he is visualized stealing a large gold cross.Footnote 62 ‘We would have all such offenders so cut off’ (3.6.108) is staged without excision as a rhetorical set-piece, a statement about conduct in war delivered for the benefit of the attendant audience of troops. In the context of concerns about the conduct of coalition forces in Iraq and Afghanistan, the only place for rhetoric in this production is when a condemnation of war crimes is required. Crucially, the Boy’s assessment concludes the episode. The camera lingers on the Boy as he stops to contemplate the significance of Bardolph’s swinging corpse. The tree from which the body hangs is located to the left of the frame, while the troops (which Nym and Pistol move to join) are seen on the right, suggesting a division of paths, a choice to be made. Most obviously, the Boy conveys the ‘rightness’ of Henry’s judgement as he physically turns away from the Boar’s Head fraternity to follow the army on its onward march. In Sharrock’s film, then, the traditional Henrician rejection of Bardolph is displaced onto the Boy in such a way as to play up the humanitarian significances of the protagonist’s stance on military ideals.

The episode’s reification of standards looks backwards to the manner of York’s death and forwards to the prisoner scenes. Distinctively, and again in contrast to Branagh’s film, in which, as the director states, ‘I rather flunked and avoided … the issue’, Sharrock’s production includes both deathly royal directives – ‘Then every soldier kill his prisoners!’ (4.6.37) and ‘we’ll cut the throats of those we have’ (4.7.61).Footnote 63 The inclusion is contextualized, of course, against the background of related controversies at the Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq, at Bagram in Afghanistan, and at Guantánamo, but goes further than other contemporary representations. While the Iraq War films never explicitly realize prisoner abuse on screen, Sharrock’s period setting permits her to follow all the major theatrical productions of the last decade in featuring the prisoner scenes. (Typical is the National Theatre production which has the French kill the boys and plunder the luggage, resulting in Henry’s bloody order.)Footnote 64 In Sharrock’s Henry V, Fluellen’s reference to the ‘poys and the luggage’ (4.7.1) is removed, and the decision presented in some part as an angry reaction to the news of York’s death. But the order is primarily understood in terms of the post-traumatic associations which gather about Henry in the battle scenes – the inhuman injunction over which he presides, it is suggested, can be seen as a catastrophic error emerging from exhaustion and stress.

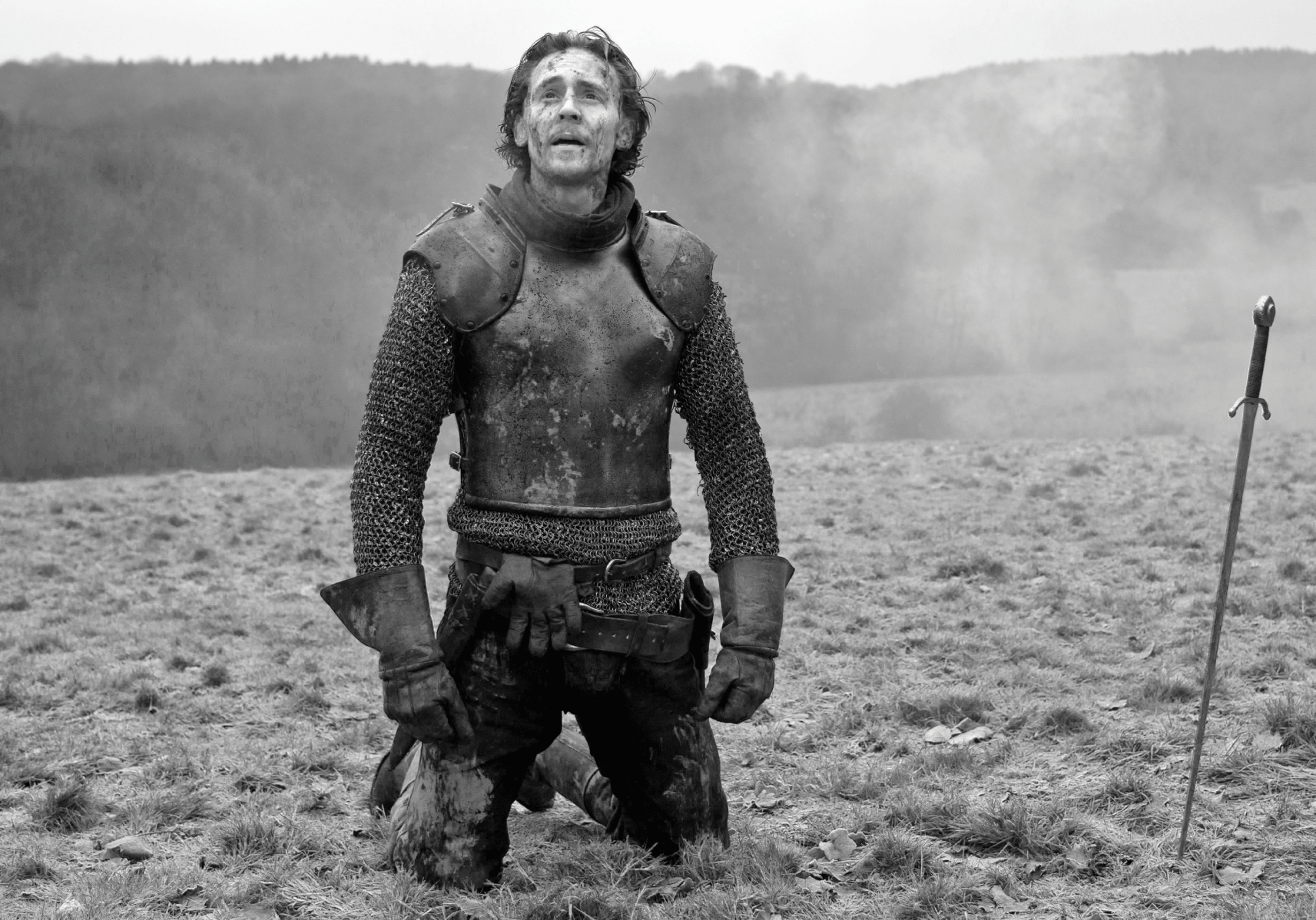

It is Henry’s traumatized condition that is pointed up in the scenes immediately preceding the order. Staggering about a burning field littered with bodies, he picks his way through numerous corpses, the mise-en-scène a spectacle of devastation that confirms, in the words of Karen Randell and Sean Redmond, ‘the relationship between trauma and witnessing a terrible event’.Footnote 65 Chiming almost exactly with cinematic representations of American soldiers in extremis, Henry’s wild-eyed expression and panicked breathing are the symptoms of a psychic disturbance triggered by exposure to battle. ‘I was not angry’ (4.7.53) is a screamed pronouncement directed heavenwards, the minor strains of strings and the reeling pans of the camera suggesting the depths of an emotional crisis. The idea of an irreparably disoriented protagonist is reflected in Essex’s startled (and interpolated) response to the order – ‘My lord?’ Simultaneously, the accompanying wide-shot of a seemingly physically reduced Henry, ringed by slaughtered men, reminds us of the overwhelming contexts underpinning his behaviour. Direct engagement with the viewer falls to the Boy whose sorrowful look to camera invites an empathetic response to Henry as a soldier pressurized into violence of action. In this way, the film not only asks us to accept that Henry orders the prisoners to be killed, but also – and uniquely – urges an audience to view that action with a degree of understanding.

The subsequent unwillingness of Henry’s men to execute the order reinforces its aberrancy while echoing the National Theatre production. There, the response of Henry’s soldiers points up, as Lois Potter notes, ‘the commander’s callous indifference’.Footnote 66 In Sharrock’s production, however, the emphasis lies with Henry’s felt participation in the fate of the prisoners and on the physical manifestations of his traumatized interiority. In a tightly sequential montage, we see the prisoners assembled for death (they kneel, with their backs to their guards), then move to a close-up of Henry’s tight face and, still with the close-up, we watch the King flinch at the prisoners’ screams as the arrows are fired. Throughout the close-up, Henry’s eyes are closed, suggesting an experience that is uncommunicable. The moment marks a transformation in Henry’s physical relationship with the camera. Distinctively, the Iraq War films have inaugurated a different – and more distanced – relation with viewers: the contemporary war hero is shot side on, head bowed, eyes averted. And, from this point in Sharrock’s film, Henry, while remaining centre-frame, increasingly looks away from camera, gesture and bodily comportment betokening knowledge, regret and recognition of his own complicity.

The change in camera angle reflects the ways in which the episode operates in a climactic capacity; put simply, the order to kill the prisoners is seen to overshadow all else. When told that ‘The day is yours’ (4.7.84), Henry struggles to compose himself, finally falling to his knees, a posture that recalls the previous situation of the prisoners and suggests that their fate has become part of the film’s psychic memory. Like Exeter’s traumatic memory at the start, the French prisoners’ fate subsequently haunts the action. ‘Praisèd be God’ (4.7.86) and ‘Then call we this the field of Agincourt’ (4.7.88) are commensurately downbeat and understated, played as tokenistic gestures emptied out of any meaningful substance. Similarly, when Henry reads aloud the ‘note’ (4.8.80) of ‘English dead’ (4.8.102), simultaneous shots of blinded noblemen and mutilated soldiers, and the general air of demoralization and deadened sensitivities, unhinge any note of affirmation (Figure 2). In this respect, Sharrock’s film throws into sharp relief the equivalent sequences in the National Theatre production where spectators were ‘invited to read the celebration of the victory at Agincourt as an analogue for British and American action in Iraq’.Footnote 67 In 2003, the year of the National Theatre production, it was still possible to imagine ‘victory’ in the War on Terror, but today, a decade and a half later, ‘the actual experience of war after 9/11 [has] demolished all such expectations’.Footnote 68 Instead, Sharrock’s film mirrors the view widely held in both popular and military realms that the costs of conflict are out of proportion to the outcome and that there never will be any kind of ‘victory’ – that its very prospect is unrealizable. Traditionally, critics have argued about whether adaptations of Henry V are pro- or anti-war. In representing a new kind of warfare, Sharrock’s film moves beyond these debates and suggests their contemporary irrelevance. Envisaging conflict as self-defeat, the film speaks to incompleteness, irresolution and regret as the only available realities.

The Homecoming and Commemoration

Even though we remain in France, Act 5’s alteration in pace and mood signals the idea of a return, recalling a cycle of war films whose narrative trajectories are often directed towards the homecoming that concludes a ‘tour of duty’.Footnote 69 Like the returning soldiers of The Hurt Locker and American Sniper, Henry is awkward in the unfamiliar domestic setting and his civilian velvet. Of course, the film’s framing device (we begin and end with Henry’s funeral) and construction – through the representation of the weeping widow – of a ‘love match’ helps make plausible the romancing of Katherine. Yet it is the echo of the homecoming that really makes sense of the scene: Henry’s uneasiness is situated as an inevitable accompaniment of the traumatized soldier’s difficult reintegration, thereby imbuing the episode – often stilted in production – with a naturalized logic. As the French King joins the pair’s hands, a match-cut from a close-up of a smiling Katherine moves us to a close-up of her grieving at his funeral. The dissolve from left to right underwrites the change in her circumstances (and clarifies the status of the wooing scene as the princess’s private commemoration). Reinforcing the course of a journey from mortality to vitality and back again, the mise-en-scène reverses the earlier match-cut from Henry’s corpse to the monarch alive and astride his horse, bringing the narrative full circle. Skilful elisions between Act 5 and the film’s epilogue inhere in the repetition of the ‘Amen’ (Burgundy’s prayer is echoed in Canterbury’s funeral mass) and in the close-up on the baby, who is, of course, both the ‘Issue’ (5.2.344) anticipated in the French King’s speech and the unfortunate offspring, ‘in infant bands crowned King’ (Epilogue, 9). Act 5, then, returns us to our starting point in a structural move which mimes the ways in which, in the Iraq War films, non-linear narratives register, as Guy Westwell notes, ‘the circular, endless, and ultimately impossible task of imposing order’.Footnote 70

Further bringing things full circle is the camera’s focus on the Boy, who is pictured gazing at the corpse while cradling the production’s most eloquent symbolic property – York’s bloodied flag. When exactly, according to the play, the Boy dies Shakespeare does not make clear, but most directors choose to stage his death. Uniquely, Sharrock’s adaptation leaves the Boy alive. The film’s third and final match-cut takes us, in a downwards–upwards movement, from a Boy to an old man (a veteran), a switch that moves the action on fifty years. Just as veterans figure as voices of experience on commemorative occasions, and their autobiographies are placed on record, Sharrock’s film constructs the Boy as the last survivor of the French campaign. The grown-up Boy – now played by the late John Hurt, an actor whose ravaged countenance underscores the costs of cyclical wartime experience – is revealed as having voiced the Chorus. And, as the now fully orchestrated score rises to a crescendo, the Chorus directly addresses the camera for the first time. The epilogue is quoted almost in full, but a single cut significantly adjusts the conventional petition to the audience. In the play, the plea ‘for their sake, / In your fair minds let this acceptance take’ (13–14) asks for the actors and the staging to be viewed favourably. Thanks to the loss of the meta-theatrical reference – ‘oft our stage hath shown’ (13) – in Sharrock’s film, it is the medieval soldier (rather than the theatrical performer) who features as subject. The final request, then, is to look on Henry, his army and his actions with compassion, to acknowledge the new realities of war and to accept the playing-out of a flawed humanity.

Via the traumatic experiences we have been pressed to remember, Henry, York and the English troops take on a larger representativeness. Just as the play’s epilogue looks forward to the next instalments in the history, so does Sharrock’s anticipate the myriad wars to come. Divorced from its theatrical provenance, ‘for their sake’ echoes the familiar motto of ‘Remembrance Day’, dedicated to the memory of all military casualties across the Western world. Enfolding the epilogue and ‘Remembrance Day’ still further is the idea of an appeal (as in the ‘Poppy Day Appeal’) to conscience and good will. Bridging Agincourt, Afghanistan and Iraq, Sharrock’s Henry V offers a bleak and inglorious vision of warfare as a continuum, a universal. The film merges the insights of contemporary theatrical and filmic interpretation to suggest the present as a recapitulation of the past, and to affirm war crimes – the misconduct of troops and the mistreatment of prisoners – as realities for which there is sustained historical precedent. Sharrock’s Henry V realizes the protagonist in elegiac fashion, and vital to this understanding is the construction of Henry’s damaged heroism and its inherent capacity for error. It is a vision replicated in the way in which, out of favour for many years, a cyclical presentation of the history plays is increasingly becoming the dominant paradigm.Footnote 71 Playing the Henriad in this way accentuates a mourning note, a serial concern with the inevitability of war, the transience of governance, the vulnerability of kings, and the plaintiveness of the historical process. The features of the individual play alter in the long shadow cast by the War on Terror, and the Shakespeare who emerges is darker and more doubtful than ever before.