Book contents

- The Cambridge Companion to Women in Music since 1900

- Cambridge Companions to Music

- The Cambridge Companion to Women in Music since 1900

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Figures

- Boxes

- Notes on Contributors

- Preface

- Abbreviations

- Part I The Classical Tradition

- Part II Women in Popular Music

- Part III Women and Music Technology

- Part IV Women’s Wider Work in Music

- Appendix: Survey Questions for Chapter 14, The Star-Eaters: A 2019 Survey of Female and Gender-Non-Conforming Individuals Using Electronics for Music

- Select Bibliography

- Index

- References

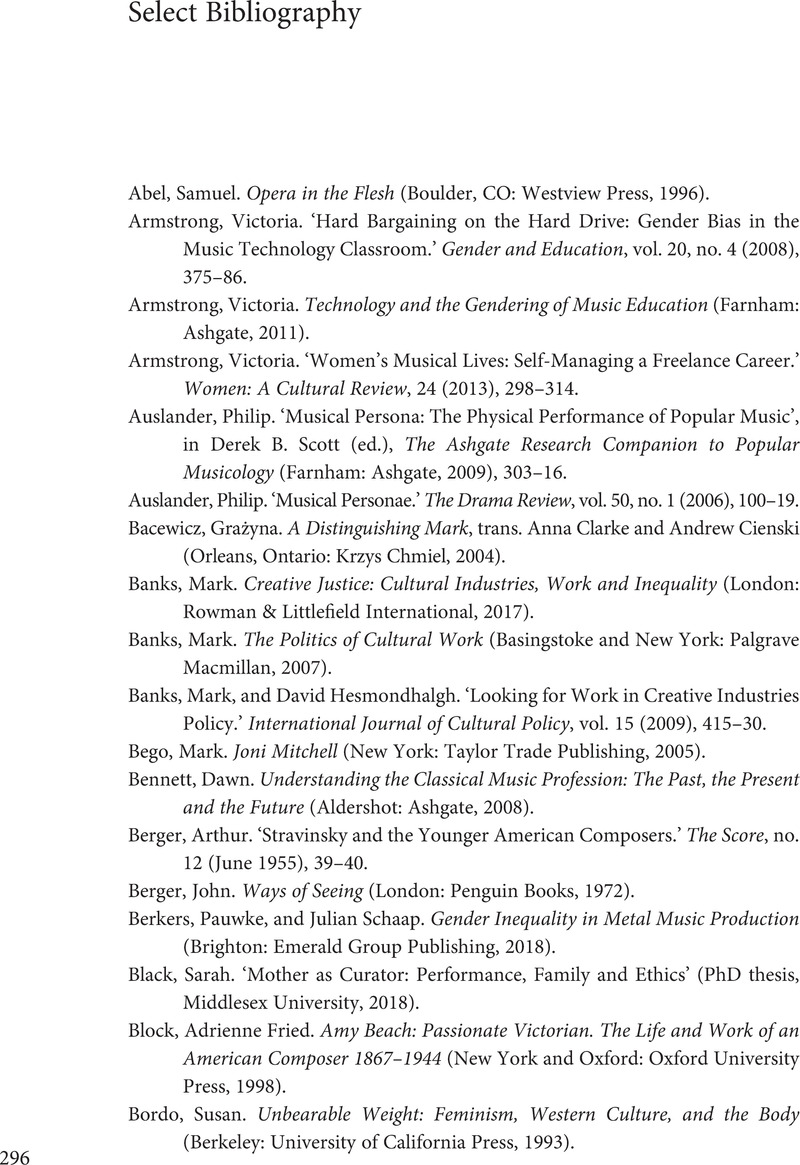

Select Bibliography

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 17 April 2021

- The Cambridge Companion to Women in Music since 1900

- Cambridge Companions to Music

- The Cambridge Companion to Women in Music since 1900

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Figures

- Boxes

- Notes on Contributors

- Preface

- Abbreviations

- Part I The Classical Tradition

- Part II Women in Popular Music

- Part III Women and Music Technology

- Part IV Women’s Wider Work in Music

- Appendix: Survey Questions for Chapter 14, The Star-Eaters: A 2019 Survey of Female and Gender-Non-Conforming Individuals Using Electronics for Music

- Select Bibliography

- Index

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- The Cambridge Companion to Women in Music since 1900 , pp. 296 - 307Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2021