I Development Context

Bangladesh showed strong resilience and dynamism by rising rapidly from the ruins of a war-devasted economy in 1972 that was characterised by a high incidence of poverty (around 80%), low per capita income (less than US$ 100), and badly damaged infrastructure. In 2015, Bangladesh crossed the threshold of the World Bank–defined lower middle-income country category. In financial year (FY) 2018, per capita income stood at US$ 1,767 in current prices, the poverty rate was estimated at around 22%, and GDP growth accelerated to 7.7%.Footnote 1 Buoyed by these accomplishments, Bangladesh now aspires to achieve upper middle-income country status and eliminate extreme poverty by FY2031. The target GDP growth rate from FY2019 to FY2031 is around 9% per year (Government of Bangladesh, 2019a).

II The Public Resource Mobilisation Challenge

A macroeconomic framework has been prepared in the context of the Government’s perspective plan 2041 (PP2041).Footnote 2 The projections are built around major changes in policies and institutions. The public resource mobilisation task is particularly challenging: it seeks to raise total revenues as a share of GDP from 10% in FY2018 to 20% by FY2031 and to raise tax revenues from 8.7% to 17.4% over the same period. This amounts to a near doubling of the tax and total revenue mobilisation efforts over 12 years. The ability to achieve the tax effort target will determine the success of the total revenue mobilisation effort.

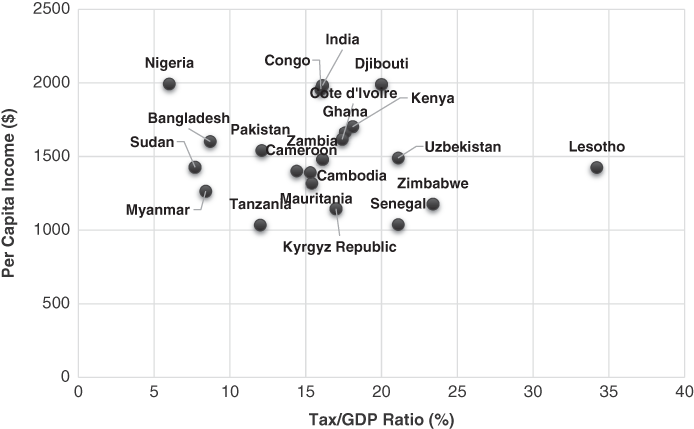

As against these ambitious tax targets, the tax performance in recent years is summarised in Figure 6.1. The tax to GDP ratio has grown modestly over the past 28 years (3 percentage points on aggregate). In more recent years (FY2010–FY2018), the tax to GDP ratio has basically stagnated, fluctuating around 9% of GDP. This is the lowest tax performance in South Asia and among the lowest in the world (Figure 6.2). Clearly, the PP2041 tax and revenue targets are overwhelmingly large in relation to the actual performance so far and present a huge policy challenge.

Figure 6.1 Trend in taxation (tax to GDP ratio) (%).

Figure 6.2 Tax performance: tax to GDP in 2017.

One major consequence of this low tax effort is the increasingly constrained fiscal space. Fixed obligations like civil service salaries, defence spending, office supplies and materials, the interest cost of the public debt, and transfers (subsidies, pensions, local government grants, and transfers to state-owned enterprises) are increasingly eating up the low level of available revenue resources (taxes and non-tax revenues), leaving little space for the development spending needed to support GDP growth and human development (Figure 6.3).

Figure 6.3 Declining fiscal space (% of total revenues).

III Main Objectives, Methodology, and Approach of the Chapter

Main objectives: The main objective of this chapter is to provide a diagnostic analysis of institutional and political economy constraints to tax reforms and tax revenue mobilisation in Bangladesh. It is particularly surprising that tax revenues as a share of GDP have virtually stagnated at a low level of 9% of GDP, at a time when the economy has been most buoyant in terms of the GDP growth rate. This chapter seeks to provide an analysis of this development puzzle, with an emphasis on the institutional dimensions.

Specifically, the objectives are:

to make a comparative assessment of the tax effort in Bangladesh vis-à-vis other countries;

to identify and evaluate the institutional constraints to tax revenue generation in Bangladesh;

to understand how political patronage affects the tax effort and impedes the implementation of tax reforms; and

to suggest ways to improve tax performance in Bangladesh.

Methodology: The international literature recognises that there are a number of reasons why tax performance on average tends to be lower for low-income countries compared with high-income countries. However, there is no standard theoretical model or approach to the analysis of institutional constraints to tax performance in developing countries.

The commonly adopted approach is to combine standard economic determinants of taxes, such as per capita income, share of non-agricultural income, and easy tax handles like imports and mining, with institutional and governance variables, such as the corruption index and estimates of the role of institutional and governance variables using econometric techniques. This approach has been formalised by Bird et al. (Reference Bird, Martinez-Vazquez and Torgler2014). They argue that the traditional approach to estimating tax effort that uses per capita income and measures of tax handles is deficient in that it only looks at the supply-side factors, while ignoring the demand-side variables. The demand factors that reflect the society’s willingness to pay must be included when carrying out a fuller analysis of the determinants of tax performance. The demand-side factors are essentially a number of institutional variables that impact on the society’s willingness to pay and to comply voluntarily with the tax laws. The institutional variables include quality of governance, country risk, regulation of entry, income inequality, and fiscal decentralisation.

This chapter follows this approach and looks at both supply- and demand-side variables in explaining the tax performance in Bangladesh. Given time and resource constraints, a full-fledged model for tax effort along the lines advocated by Bird et al., and its econometric estimation, is not possible. The analysis underlying this chapter is essentially based on a desk review of existing literature and an analysis of the Bangladesh tax database provided by the NBR and the Ministry of Finance, tax administration, and tax reforms. In looking at institutional constraints and implications for tax performance, it reviews the relevant literature and summarises the implications of the findings of relevant econometric studies for Bangladesh tax reforms and tax performance. Drawing on the findings of international experience, it seeks to relate the various institutional and administrative constraints to explain the failures in tax performance and tax reforms in Bangladesh, and the way forward.

The analysis has benefited from the author’s long-standing and deep understanding of the tax mobilisation effort and related institutions in Bangladesh, first while he was Sector Director of the Economic Management Team of the South Asia Region of the World Bank (2001–2006) and subsequently as Vice Chairman of the Policy Research Institute of Bangladesh (2009–present). In both capacities, the author has conducted policy analysis, dialogue, and discussions of tax reforms with officials of the National Board of Revenue (NBR) and the Ministry of Finance. He also has a solid understanding of various governance and institutional challenges of tax reforms in Bangladesh.

IV Tax Mobilisation Issues in Developing Countries: The Lessons from International Experiences

There is a huge literature on the analysis of tax performance in developing countries. The literature compares tax performance between developed and developing countries, and tax performance over time. It also shows how the tax policy debate and advice for developing countries has shifted over time, including the underlying economic theory and analysis. Importantly, it brings out the political economy and institutional dimensions of tax reforms that have tended to be neglected in early economic analysis and policy advice on tax mobilisation but that now occupy a dominant role in tax analysis and policy advice. Useful summaries include: Besley and Persson (Reference Besley and Persson2014); Bird et al. (Reference Bird, Martinez-Vazquez and Torgler2014); Bird (Reference Bird2012); Bird and Bahl (Reference Bird and Bahl2008); Bird and Zolt (Reference Bird and Zolt2003); Gordon and Lie (Reference Gordon and Li2005); and Tanzi and Zee (Reference Tanzi and Zee2001).

The main messages and lessons from the tax mobilisation experience of developing countries that have a bearing on the analysis of tax performance in Bangladesh include the following:

On average, the tax to GDP ratio is substantially lower for developing countries (17–18%) as compared with developed countries (33–34% of GDP).

There are wide variations in tax performance within each country group for both developing and developed countries.

While on average the tax to GDP ratio tends to rise with per capita income, this is not a linear relationship. The relationship is statistically significant only for low-income countries.

The tax structure shows that developed countries on average rely much more on personal income taxes, while developing countries rely substantially more on consumption and international trade taxes.

Over the past 50 years or so, two major changes have happened to the tax structure globally: many more countries have adopted a value-added tax (VAT), and countries have tended to lower the average tax rates on income (the so-called flattening of statutory income tax rates).

There is no theoretically determined optimal level of taxation. The size of tax collection depends on the political economy of government services and social preferences.

All taxes in practice impose a cost on the economy, both in terms of tax collection costs and economic costs generated through the effects of taxation on economic behaviour. A good tax system should seek to reduce these costs to the extent possible.

There is a growing recognition that the level and composition of taxes in any country is essentially an outcome of tax institutions and political economy, rather than determined by any theoretical model of taxation. Accordingly, tax reforms that ignore political economy and institutional factors are not likely to succeed.

V Determinants of Tax Performance in Bangladesh

A Supply-Side Variables

1 Level of Development and Tax Handles

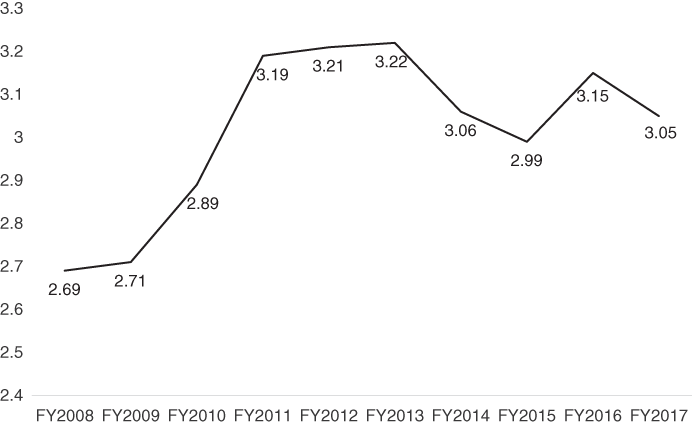

The most fundamental issue is why the tax to GDP ratio has remained stagnant at around 9% of GDP over the past decade or so, despite rapid strides in GDP growth that have led per capita income to accelerate in current prices from US$ 800 in FY2010 to US$ 1,767 in FY2018. In constant 2010 dollars, this amounts to US$ 1,535 in FY2018, a healthy 8.5% annual growth in real per capita income. The very low tax performance of Bangladesh relative to countries at a similar per capita income level is striking (Figure 6.4), suggesting that Bangladesh is a negative outlier in the area of tax performance. This suggests that the low level of development is not the main concern but that there are other factors at play, including the Government’s tax reform efforts, tax administration, and willingness to pay.

Figure 6.4 Tax performance in comparable countries in 2017 (per capita income US$ 1,000–US$ 2,000).

The tax performance model formalised by Bird et al. identifies several supply-side variables: per capita income; share of agriculture in GDP; size of the informal economy; access to natural resources; and share of trade in GDP. The latter two variables reflect the availability of easy tax handles.

The low per capita income relative to developed countries explains a part of the reason for the low tax to GDP ratio in Bangladesh. But, as noted, the low level of per capita income alone cannot explain the poor tax performance in Bangladesh because its tax to GDP ratio is only 50% of the average tax to GDP ratio in developing countries.

Regarding the roles played by the share of agriculture and the size of the informal economy, again they are a part of the factors that account for the low average tax ratio for Bangladesh relative to developed countries, but they do not explain the very low tax to GDP ratio for Bangladesh relative to other developing economies. Moreover, the GDP share of agriculture has fallen sharply over the years and continues to decline, while the share of the industrial sector has grown substantially. For example, between FY2013 and FY2018, the GDP share of the industrial sector grew from 29% to 34%, and the share of agriculture fell from 17% to 14%, but the tax to GDP ratio did not pick up, but instead declined from 9.5% of GDP in FY2013 to 8.7% of GDP in FY2018. Indeed, the 2018 industrial sector share in Bangladesh (34%) is substantially higher than the average for low-income countries (25%), yet the tax performance is substantially weaker than the average for low-income economies.

Concerning the role of the informal economy, unfortunately reliable estimates of its size and changes over time are not available. Nevertheless, a priori it is likely to be an important contributor to the low tax performance in general. However, it is not very likely that the share of the informal economy is substantially higher in Bangladesh than the average for low-income economies, and therefore, it is unlikely to be a reason for the very low tax performance relative to countries with similar per capita income.

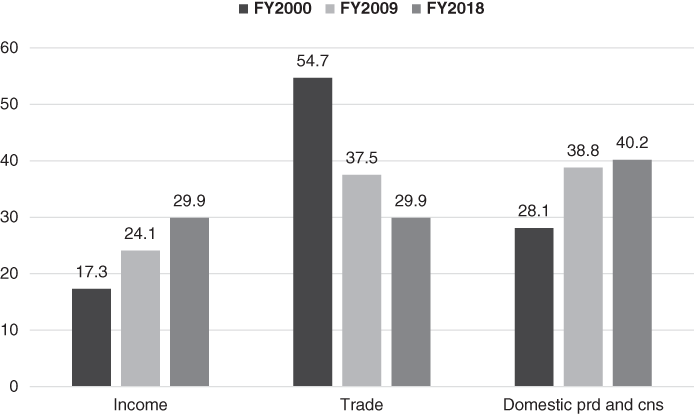

2 Tax Composition and Structure

The composition of Bangladesh tax revenues is shown in Figure 6.5. The structure of taxation in Bangladesh has improved significantly over the years. The share of income and domestic production/consumption taxation has increased, while the reliance on international trade taxation has declined. The introduction of the VAT in 1991 made a major difference to both improving the tax structure and increasing the tax to GDP ratio. Thus, the increased role of domestic production/consumption taxation reflects the growing importance of the VAT in revenue generation. This is a positive development; yet the revenue yield of the VAT has been stagnant since FY2011 (Figure 6.6). When compared with the statutory VAT rate of 15%, the low yield is indicative of the low productivity of the VAT.

Figure 6.5 Bangladesh tax structure (% share in total taxes).

Figure 6.6 VAT revenue yield (% of GDP).

A useful way of assessing the quality of the tax structure is to compare the Bangladesh experience with other countries. Using data from the International Monetary Fund’s (IMF’s) International Financial Statistics for the years 1996–2001, Gordon and Li (Reference Gordon and Li2005) summarise the results of the international tax structure by income groups, as illustrated in Table 6.1. The income groups were selected from the World Bank classification of low-income (below US$ 745); lower middle-income (US$ 746–2,975); upper middle-income (US$ 2,979–9,205); and upper-income (greater than US$ 9,206) prevailing during 1996–2001. Although the data in the table are a bit outdated, it illustrates well the major differences in the observed tax structure by income groups, which is not likely to change much with updated data. However, the relative weakness of the Bangladesh tax structure will likely be magnified.

Table 6.1 Sources of government revenue, 1996–2001

| GDP per capita | Tax revenue (% of GDP) | Income taxes (% of total taxes) | Corporate income taxes (% of total income taxes) | Consumption and production taxes (% of total taxes) | International trade taxes (% of total taxes) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <US$ 745 | 14.1 | 35.9 | 53.7 | 43.5 | 16.4 |

| US$ 746–2,975 | 16.7 | 31.5 | 49.1 | 51.8 | 9.3 |

| US$ 2,976–9,205 | 20.2 | 29.4 | 30.3 | 53.1 | 5.4 |

| All developing | 17.6 | 31.2 | 42.3 | 51.2 | 8.6 |

| >US$ 9,206 | 25.0 | 54.3 | 17.8 | 32.9 | 0.7 |

| Bangladesh (FY2018) | 8.7 | 29.9 | 51.0 | 40.2 | 29.9 |

Table 6.1 tells a useful story about the international experience with the modernisation of the tax structure as income grows and development proceeds. The main messages are set out in the following paragraphs.

First, the survey confirms that the tax to GDP ratio correlates positively with per capita income on average. Related to this, in order for the tax to GDP ratio to increase with income growth, the structure of taxation should be such that it responds well to income growth. In other words, the tax structure must be buoyant with respect to the expansion of economic activities, as reflected by the level of GDP.

Second, as development proceeds, the share of income taxes grows. Indeed, developed countries raise more than 50% of their revenues from income taxes. The rationale for this is based on the need to have a tax structure that meets three desirable principles of taxation: the ability to pay; equity principles of taxation; and the buoyancy argument.

Third, developed and upper middle-income countries rely much more on personal income taxes relative to corporate taxes. Thus, developed countries obtain as much as 45% of their total tax revenues from personal income taxes; corporate taxes account for less than 10% of total tax collections. The rationale here is that unduly high taxation of the corporate sector would tend to reduce investment incentives and lead to capital flight, which would hurt growth.

Finally, as development proceeds, the revenue role of international trade taxes tends to disappear. Thus, it accounts for less than 1% of total tax revenues for high-income countries and around 5% for upper middle-income countries. Even lower middle-income countries get less than 10% of their tax revenues from international trade taxes. The rationale for this is that trade taxes tend to distort resource allocation, hurting exports, and breeding inefficiency within domestic production.

Against this international evidence, the Bangladesh tax structure has many shortcomings. Bangladesh continues to rely very heavily on international trade taxes (30%), as compared with less than 9% for all developing countries. Even the low-income countries on average get only 16% of their revenues from international trade taxes, which is nearly 60% lower than in Bangladesh. This heavy reliance of Bangladesh on international trade taxes is a seriously negative policy development and indicates the distortionary effect of the tax structure.

The improvement in the performance of income taxes is a positive outcome. It is now roughly comparable with the average for low-income economies. But there are a number of major concerns. Although the share of income taxes from the corporate sector has been falling, it still accounts for more than 50% of income taxes. Corporate tax rates vary considerably by activities, with a heavy load on a few cash cows. Some sectors like mobile phone services, tobacco, and banks are required to pay hefty profit tax rates ranging from 40% to 45%. They account for most of the corporate tax yield. There are many exemptions that lower the average yield of corporate taxes.

A major issue of the tax structure is the very low yield from personal income taxes (Ahmed, Reference Ahmed2015). Very few people pay personal income taxes. Bangladesh does not have a universal income tax base, owing to exemptions of many sources of income and the very low taxation of capital gains. In addition, tax compliance is very low. The poor performance of personal income taxation is one of the primary reasons for the low tax buoyancy in Bangladesh, which has constrained the overall tax performance. Sadly, this also speaks volumes about the inequitable nature of the tax structure. Income inequality has grown substantially in Bangladesh, but the collection of personal income taxes has not increased much.

Finally, as noted, the productivity of the VAT has been stagnant, owing to many exemptions and inadequate coverage. This is yet another factor that explains the low buoyancy of the Bangladesh tax structure.

B Willingness to Pay: Demand-Side Issues

Bird et al. (Reference Bird, Martinez-Vazquez and Torgler2014) have argued convincingly that ‘a more legitimate and responsive state appears to be an essential precondition for a more adequate level of tax effort in developing countries’. They capture this effect of social and political institutions on tax performance by developing a fuller model of determinants of tax performance that includes the traditional supply-side variables as well as demand-side variables. Using cross-country data for mean values for 1990–1999 for 110 developing countries, they estimate the tax performance model (tax to GDP ratio) using a various mix of supply- and demand-side variables. The structure of the economy (measured by the GDP share of non-agriculture sectors), representing the supply side, and quality of governance (measured by the World Bank governance indicators and the International Country Risk Guide (ICRG) index), representing the role of institutions or demand-side variables, yield the most robust results. They conclude that institutions are a major determinant of tax performance.

Other econometric studies provide similar supportive evidence about the role of institutions in explaining tax performance (Ghura, Reference Ghura1998; Gupta, Reference Gupta2007; Nguyen, Reference Nguyen2015; Ricciuti et al., Reference Ricciuti, Savoia and Sen2019). Ghura (Reference Ghura1998) focuses directly on the role of corruption in explaining tax performance in African countries and finds that corruption is significantly and negatively correlated with tax performance. Using panel data over 25 years for 105 developing countries, Gupta (Reference Gupta2007) finds a negative contribution of corruption to tax performance and a positive contribution of political stability. Nguyen (Reference Nguyen2015) finds evidence that institutional quality has a significant positive impact on tax performance in low-income and lower middle-income countries. Ricciuti et al. (Reference Ricciuti, Savoia and Sen2019), in their empirical research focusing on the role of political institutions in building tax capacity, find evidence that the existence of effective constraints on the head of the government makes the tax system more accountable and transparent.

The governance challenges facing Bangladesh are well known. For example, an international ranking of corruption prepared by Transparency International puts Bangladesh at the bottom 15% of the countries ranked (149 out of 175 countries) for 2018. The World Bank governance indicators (2017) rank Bangladesh as follows: voice and accountability (bottom 30th percentile); political stability and absence of violence/terrorism (bottom 10th percentile); government effectiveness (bottom 22nd percentile); regulatory quality (bottom 21st percentile); rule of law (bottom 28th percentile); and control of corruption (bottom 19th percentile). These results suggest that there are major governance issues and challenges in Bangladesh that might serve to constrain tax performance. Drawing from the econometric evidence summarised above, it is most likely that corruption and other elements of weak governance are major factors for the low tax collection in Bangladesh.

The adverse impact of corruption on Bangladesh’s economic management is well recognised. It tends to operate through four main channels: land markets; financial markets; public procurement; and taxation. The corruption in tax administration is pervasive. This is a major factor underlying low tax compliance in all areas of taxation, which is a major constraint to tax revenue mobilisation.

The weakness on the demand side raises an important political economy issue. Are Bangladeshis unwilling to pay taxes because they do not feel that resources are used effectively? This is an empirical question that needs further research before an answer can be provided, but some preliminary observations can be made.

There is at least some degree of truth that higher tax collection is possible if citizens can see more and better public service provision in areas related to health, education, water, sanitation, and drainage. In developed countries, these services are typically provided by local government institutions. Bangladesh, on the other hand, is heavily centralised. While there are elected local government institutions, they are highly resource constrained in the absence of fiscal decentralisation (Ahmed, Reference Ahmed2017). Local government institutions collectively raise a meagre 0.16% of GDP as tax resources in Bangladesh (Ahmed, Reference Ahmed2017), as compared with an average of 6.4% of GDP in industrial countries and 2.3% of GDP in developing countries (Bahl, Linn, and Wetzel, Reference Bahl, Linn and Wetzel2013). Better services can also provide greater resource mobilisation through greater use of cost recovery policies (non-tax revenue measures). Strengthening of local government institutions and the associated fiscal decentralisation associated with more and better basic public services can certainly play a major role in increasing tax and non-tax revenues in Bangladesh.

However, there is also evidence that the demand for public services is growing in Bangladesh, and the Government has been making some efforts to respond to them. The budget making process involves considerable public consultation with various citizens groups, including business, non-governmental organisations, research and think tank institutions, and the media. This is conducted at quite a high level, involving the Finance Minister. The budget is also debated in the Parliament. The public consultation process is fairly open and considerable discussions about expenditure priorities and tax reform options are aired in these consultation process. The importance of increasing allocations for health, education, social protection, and infrastructure are raised every year. In response, the Government has done a fairly good job in keeping broad expenditure priorities focused on the development agenda. The Government has also protected total public expenditure as a share of GDP from falling despite shortfalls in revenues by running a budget deficit that is financed by foreign and domestic borrowing. This deficit has grown slightly over the past 10 years but is now capped at around 5% of GDP as a part of the Government’s self-imposed fiscal discipline.

The Government’s response to the need for tax reforms has also been positive in recent years, with as many as three reform efforts in the past eight years, but implementation has lagged behind due to political economy and administrative capacity considerations. These are discussed in detail in the next section.

The budget debate and discussions in the Parliament are less productive than they could be because the Parliament is usually dominated by the government in power. Tax issues are often raised and discussed but not in a forceful way that could bring about major changes. Additionally, the time when the budget is shared with the Parliament is less than a month before the current fiscal year ends and the new fiscal year begins. The budget is already approved by the cabinet and the prime minister, and the documents are printed. This leaves very little time and opportunity for any substantive budget debate and discussion in the Parliament. This is one area where the budgetary consultation process could be improved. One possible option is to involve the appropriate Parliamentary Committee responsible for oversight on budget and finance issues early in the process of budget making, to get timely inputs into the process. Another possible step would be for the Parliamentary Committee on budget and finance to request national researchers to prepare background papers on tax and expenditure issues and to discuss these with the committee early in the budget process. They could also seek technical assistance on the draft budget as inputs to their own review and discussions.

The Cabinet review of the draft budget could also be made more productive by requiring each Cabinet minister to make a presentation on their development targets and objectives for the year, and how adequate the proposed resource allocations are. Stronger participation by the Cabinet members in the budgetary process could be very useful in bringing out the internal tensions and the challenges posed by the revenue constraints upfront, so as to allow proper policy choices to be made, including the need for meaningfully strengthening revenue mobilisation. The Cabinet could also seek a technical briefing by NBR on the reasons for stagnant tax performance, and possible solutions.

VI Tax Reform Efforts and Implementation

Governance constraints not only impinge on citizens’ willingness to pay and contribute to the low regard for tax compliance, they also adversely affect tax reform efforts and the quality of tax administration. The tax reform experience in Bangladesh provides evidence that weak governance has been a major constraint on tax performance.

A Major Tax Reforms

A large part of the reason for the low tax performance and weak and stagnant revenue structure is the relative absence of tax reforms in Bangladesh. Tax reforms have generally taken a back seat in Bangladesh. The first and only successful major tax reform was carried out in 1991, when the VAT was introduced. This was the only tax reform that succeeded, despite considerable hiccups. The introduction of the VAT also coincided with a major reduction in trade protection, involving the removal of most quantitative restrictions and a cut in customs duties during the 1990s (Ahmed and Sattar, Reference Ahmed and Sattar2019). Since then, the tax system has been occasionally tweaked, particularly in the area of international trade taxes over the 2000–2010 period, but the underlying motivation was to reform the heavily protected trade regime often as condition for access to international aid. These second-phase reforms of the customs duties did not yield much benefit in terms of a reduction in trade protection. Indeed, once the heavily protected trade regime was brought down to more moderate levels during the first phase of trade and investment deregulation in the 1990s, trade taxes re-emerged as a major tool for revenue mobilisation based on the introduction of a complex system of regulatory and supplementary duties (Ahmed and Sattar, Reference Ahmed and Sattar2019).

The Government sought to re-engage in tax reforms in FY2011, when it announced a major Tax Modernisation Plan (NBR, 2011). This reform was a part of the FY2011 budget, although this was not converted into a law. The Government’s Sixth Five-Year Plan incorporated the main features of the Tax Modernisation Plan in articulating its macroeconomic framework and associated policy reforms. This was a fairly ambitious reform effort that sought to modernise the Bangladesh tax system, including reforms of tax laws, tax institutions, tax administration, and capacity building. The record shows little progress in its implementation: some limited progress was achieved in the computerisation of VAT administration, but overall tax administration remains as constrained as before.

A third attempt at tax reform happened in 2012, prodded by the IMF. As a part of its Extended Credit Facility agreement with the IMF, the Government adopted a new VAT reform act, called the ‘VAT and Supplementary Duty Act 2012’, which aimed at modernising and expanding the scope of the VAT. The reform promised to improve the efficiency of VAT collection and to raise substantial new revenues. However, the 2012 VAT Law remains on paper only and has not been implemented, in view of opposition from politically well-connected vested interest groups.

Finally, the new government elected in 2018 has now announced another round of tax reform in the National Budget FY2020 (Government of Bangladesh, 2019b). It has adopted the PP2041 as the long-term development vision and seeks to initiate implementation of the underlying macroeconomic and fiscal framework. In this regard, it has acknowledged the dismal tax performance in the past and seeks to change this by setting a lofty goal of increasing the tax to GDP ratio by an unprecedented 3% of GDP in one year. This massive tax target is to be achieved by focusing on the implementation of a revised version of the 2012 VAT Law and by strengthening income tax administration. Preliminary assessment of the proposed tax reforms suggests that the proposed tax reforms are inadequate and will not yield the desired revenue outcome (Ahmed, Reference Ahmed2019). There may be some marginal improvements in the tax to GDP ratio, but a substantial improvement will not be possible based on the inadequate reform proposals. The budget did not specify what institutional reforms will be undertaken to help mobilise such a massive increase in the tax to GDP ratio. Even the revised VAT 2012 proposal was not well defined in terms of which VAT rate would apply to which activities, and how it would be administered.

B Discretionary and Discriminatory Tax Treatment

Although the only successful major tax reform happened in 1991, in the context of the annual budget cycle, the tax laws/rules/regulations are invariably modified to introduce new measures or to provide exemptions or special tax treatments for activities or entities. This is most prevalent in the area of customs duties and the VAT. These annual interventions are mostly conveyed through the Statutory Regulatory Order (SRO). While it is understandable that budget management needs flexibility and reform measures are needed to increase revenues, the main issue with these annual interventions is that they are not based on proper analysis of the revenue and resource allocation effects of the interventions. More often than not, tax measures are ad hoc and based on easy tax handle considerations. For example, the annual changes in income tax measures tend to target easy handles such as tobacco, mobile telephone operators, and the banking sector. The VAT/customs duties tend to target imports. Indeed, to compensate for the revenue and protection loss from tariff reforms, a range of special supplementary duties and regulatory duties have mushroomed, which has offset the positive effects of tariff reforms on resource allocation, seriously distorted trade incentives, and hurt exports (Ahmed and Sattar, Reference Ahmed and Sattar2019). Furthermore, the reduction in the predictability of tax laws is an important constraint on the investment climate for the private sector.

Importantly, the introduction of exemptions and special tax treatment of activities/entities not only dilutes the transparency and predictability of tax policies, it substantially reduces the effectiveness of the tax base and is a major factor for lowering the revenue yields of the tax system. In most instances, these exemptions and special treatments, and often new budget measures, especially those related to trade taxes, are dictated by the political power of the beneficiaries. The potential revenue loss and adverse consequences for resource allocation (especially through the distortion of trade policy) are of no consequence. The large prevalence of discretionary and discriminatory tax interventions also creates room for corrupt practices by the staff of the NBR.

The way SROs reduce the transparency and predictability of the tax system is illustrated dramatically by a review of customs duty–related SROs issued between FY2015 and FY2019. As many as 926 SROs were introduced, each aimed at providing a special benefit to a target group. A sample from this long list of SROs is provided in Annex 6.1, to give a flavour of the kind of negotiated settlements that happen in taxation in Bangladesh. In most cases, these special treatments were allowed as a response to political lobbies by the beneficiary group. There are similar SROs related to income tax, the VAT, and regulatory/supplementary duties. The SROs are also a good illustration of the absence of systematic tax policy analysis. The SROs are mostly introduced to benefit politically well-connected groups: there is almost no concern about what this does to resource allocation or tax collection. This ad hoc approach to tax policy and tax administration is a serious problem that must be addressed in order to modernise the tax system in Bangladesh.

C Political Economy of Tax Reforms

The absence of significant tax reforms in Bangladesh despite an overall buoyant economy and the growing fiscal constraint on development is a serious problem that threatens to undermine the long-term sustainability of development progress. The half-hearted attempts with the implementation of the 2011 Tax Modernisation Plan, the inability to implement the 2012 VAT Law, and the inadequacy of the latest attempt to reform the tax system in the FY2020 budget suggest a combination of inadequacy of political will and a lack of readiness to tackle the tax challenge. The transparency and predictability of the tax system is further complicated by the introduction of new budget measures every year on an ad hoc basis along, with new exemptions and special tax treatments.

The tax literature recognises the political nature of taxation (John, Reference John2006; Brautigam et al., Reference Brautigam, Fjeldstad and Moore2008; Prichard, Reference Prichard2010; Bird et al., Reference Bird, Martinez-Vazquez and Torgler2014; Besley and Persson, Reference Besley and Persson2014; Ricciuti et al., Reference Ricciuti, Savoia and Sen2019). One important piece of research in the context of Bangladesh that has sought to analyse the tax reform impasse and the frequent use of ad hoc tax measures through SROs by applying the political economy lens is that by Hassan and Prichard (Reference Hassan and Prichard2014). Their paper argues that the prevailing tax system in Bangladesh is the outcome of a complex set of negotiations between formal and informal institutions based on micro-level incentives for each of the political actors. As a result, the tax system is highly informal, is administered manually rather than on an automated computerised basis, and involves high levels of discretion. This dysfunctional system is sustained because it serves the interests of powerful political, economic, and administrative actors. Specifically, ‘the current system delivers low and predictable tax rates to businesses, provides extensive discretion and opportunities for corruption to the tax administration, and acts as an important vehicle for political elites to raise funds and distribute patronage and economic rents’ (Hassan and Prichard, Reference Hassan and Prichard2014, p. v). Reform efforts are constrained by the need to preserve this ‘political settlement’. Reform outcomes are weak or they fail because the resultant negotiations that seeks to reconcile the interests of the various competing groups with the need for reforms cause the reforms to be either abandoned or weakened considerably. In this framework, the SROs are simply instruments for favour distribution through discretionary and discriminatory application of the tax laws and rules and regulations.

The research from Bangladesh and other international experiences support the hypothesis that tax reforms are essentially political in nature and cannot succeed without reform champions at the highest level. They also recognise the strong link between economic and political governance, state tax capacity, and revenue mobilisation. As with any major reform, there are winners and losers from tax reforms. The stakes are particularly high with tax reforms because substantial amounts of money are involved. The beneficiaries of the present tax system in Bangladesh (political elites, big business, and the NBR administration) are happy with the status quo. The influence of these powerful lobbies will need to be offset by reform champions within the political system and in the civil administration.

This political economy lens can help us understand why the 1991 VAT Law was successfully implemented while other tax reform efforts failed. The successful implementation of the 1991 VAT Law and hurdles faced with the implementation of the Tax Modernisation Plan 2011 and the 2012 VAT reform experiences are also consistent with the lessons from international experience that suggest that tax reforms cannot succeed if they are donor-driven or led by international advisers (Dom and Miller, Reference Dom and Miller2018). Tax reforms must be led by the Government, with the Finance Minister in the lead, strong support by the NBR, and solid political backing from the head of the government. It must also have strong technical foundations based on sound background research, and implementation support in terms of suitable administrative infrastructure, including ICT solutions.

The 1991 VAT reform met all of these conditions. The reform was home grown. The technical work was led by senior staff of NBR and supported by technical assistance from the IMF. Overall policy leadership was provided initially by a technocrat Finance Minister and subsequent ministers carried through the work to the implementation stage. An IMF fiscal expert of Bangladeshi origin was procured and stationed in Dhaka on a long-term basis. Most importantly, the reform had the political backing from all heads of the government involved from the design to the implementation phases.

The 2011 Tax Modernisation Plan was grounded in the recognition by the Finance Minister that the tax revenue was inadequate and needed to be increased substantially. Accordingly, the Tax Modernisation Plan targeted an increase in revenue by 4 percentage points of GDP over a four-year period (FY2011–FY2015). The Plan was home grown and developed by a reform-minded Chairman of the NBR. He had the initial support of the Finance Minister, who was enthused by the prospect of substantial gains in tax revenues. But this support was more personal than institutional. The nature of the reforms envisaged required the full support of the prime minister and the cabinet, but a broad-based discussion of the reforms with the prime minister and the cabinet did not happen. Importantly, technical preparations were inadequate. There was also absence of ownership at the NBR staff level. Most unfortunately, the champion of the NBR Modernisation Plan 2011, the NBR chairman, was replaced by a new chairman in 2013. Unlike in the case of the VAT Law 1991, where the reform momentum continued despite the change in government because of a continuity of core NBR staff who were pushing the reform, the change in NBR leadership, combined with the absence of strong support from the political leadership, caused the 2011 reforms to fail.

The VAT 2012 reform was mainly pushed by the IMF under the Extended Structural Adjustment Facility programme. Within NBR, the Member VAT Policy and Member Customs were the main champions. There was also a solid technical assistance programme to help with the design of the new law and its implementation. At the political level, the Finance Minister provided support. The initial delay was caused by the need for adequate preparatory work. Finally, when the NBR was basically ready to launch implementation in the context of the FY2018 budget, it faltered because of strong opposition from the retail-level trading community, represented by the politically powerful and well-organised Federation of Bangladesh Chambers of Commerce and Industry (FBCCI). This opposition was grounded in the reality that except for the large retail units, most retail-level traders are a part of the informal economy and are therefore out of the tax net. The introduction of the new VAT Law would require the exposure of transactions and earnings to NBR through proper record-keeping. In this way, they could be exposed to higher tax obligations and/or rent-seeking intrusions by the tax officials. The prime minister decided to postpone the implementation decision in view of the strong FBCCI opposition and advice from the prime minister’s political party about the potential downside risks to the party in the then upcoming 2018 national elections, which were scheduled for the end of December 2018.

The half-hearted attempt to reform the tax system in the FY2020 budget is largely explained by the inadequacy of understanding regarding the complexity of the tax challenge and by an absence of strategic thinking. The installation of a new government elected in 2018 and involving a new Finance Minister provided a major opportunity for Bangladesh to rethink its tax reforms. As noted, there was indeed some positive intent. But the review of the FY2020 budget document shows that this positive political intent is not backed by a well-defined reform strategy and adequate associated specific reforms of tax policies and tax administration. Most unfortunately, instead of implementing the well thought out 2012 VAT Law in its original form, and taking advantage of the administrative progress already made, the new Finance Ministry team developed a hodgepodge variant of the 2012 VAT Law that was not properly studied or analysed in terms of revenue impact and the nature of the administrative preparations that would be required. Additionally, ambitious tax targets for personal income tax yields were set that had no policy or administrative reform content beyond the idea of recruiting additional income tax collectors. This is unfortunately a reflection of the ‘policing approach’ to tax collection that has proven to be the bane of the income tax system, as further explained below. So, political willingness alone is not enough. It must be backed by sound tax policy analysis and administrative reforms to improve the tax system.

D Tax Administration Issues

1 Taxation of Personal Income

It is well known that weak tax administration can be a serious constraint to tax resource mobilisation in developing countries. An excellent summary of these issues and lessons learnt from country experiences is contained in Bird (Reference Bird2015). A particular challenge is the ability to administer efficient and progressive personal income taxation. Thus, a major difference between developing and developed countries is the much larger share of personal income taxation in total taxation. Bangladesh collects a mere 1.3% of GDP as personal income taxes (FY2018), and this ratio has grown only marginally (it was 1% of GDP in FY2010), even as per capita income more than doubled in nominal dollar terms and increased by 92% in real dollar terms over FY2010–FY2018.

In addition to numerous legal exemptions, at the heart of the personal income taxation problem is the low level of compliance. The estimated compliance rate is a mere 12% (Ahmed, Reference Ahmed2019). Owing to exemptions and low tax compliance, actual tax yield from personal income has grown only slowly, from a low yield of 0.41% of GDP in FY2000 to about 1% of GDP in FY2018. As compared to this low revenue yield, depending upon the level of income, the legal tax rates vary from 10% to 30% plus (when the so-called wealth taxes are added). The potential loss of revenue from exemptions and low compliance is illustrated in Table 6.2 under two scenarios. The first scenario considers an effective average tax rate of 10% on the income share of the top 10th percentile. This group has average income much higher than the tax exempted level of Bangladeshi Taka (BDT) 2,50,000. The second scenario is a bit more ambitious and involves an effective average tax rate of 15% on the income share of the top 10th percentile. With proper reforms of the income tax that would not require any increase in tax rates but better implementation, including a move towards the concept of a universal income tax base with minimum exemptions and an effective tax administration mechanism, the yield from personal income tax could reach 3.8% of GDP under Scenario 1 and 5.7% of GDP under Scenario 2. Compared to these personal income tax potential scenarios, the very low actual yield dramatically illustrates the very low productivity of the personal income tax system.Footnote 3

Table 6.2 Personal income tax productivity

| HIES | Income share of top 10% | Effective tax rate (10%) | Potential income tax (% of GDP) | Effective tax rate (15%) | Potential income tax (% of GDP) | Actual income tax (% of GDP | Tax productivity (%) (10% av. effective rate) | Tax productivity (%) (15% av. effective rate) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 38.1 | 10 | 3.8 | 15 | 5.7 | 0.41 | 10.8 | 7.2 |

| 2005 | 37.6 | 10 | 3.7 | 15 | 5.6 | 0.60 | 16.2 | 10.7 |

| 2010 | 35.9 | 10 | 3.6 | 15 | 5.4 | 0.95 | 26.4 | 17.6 |

| 2016 | 38.2 | 10 | 3.8 | 15 | 5.7 | 1.00 | 29.0 | 19.3 |

Tax evasion is particularly large at the highest levels of income. A range of factors explain this tax evasion problem, including legal tax exemptions and loopholes, political connections, corrupt practices, complexities of tax assessment and collection, inefficient tax audits, and high marginal rates of taxation. Reform efforts have focused on enlarging the tax base by bringing more taxpayers into the tax base through electronic tax IDs, annual tax fairs, and cross checks on bank accounts, utility bills, home rentals, and import transactions, etc. To improve the productivity of audits, a Large Taxpayer Unit has also been established to monitor the tax returns of large payers. These reform efforts have yielded some results. The number of registered personal income taxpayers has increased noticeably (Table 6.3), but the average nominal yield per taxpayer has been erratic, with no discernible pattern. The average return per taxpayer has fallen when accounting for inflation.

Table 6.3 Personal income tax collection efforts

| No of tax payers (ml) | Tax collection (BDT, bl) | Average yield (BDT) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| FY2011 | 1.231 | 99 | 80,366 |

| FY2012 | 1.233 | 125 | 101,079 |

| FY2013 | 1.369 | 167 | 122,075 |

| FY2014 | 1.363 | 119 | 87,109 |

| FY2015 | 1.627 | 126 | 77,173 |

| FY2016 | 1.721 | 173 | 100,691 |

| FY2017 | 2.188 | 209 | 95,612 |

These results suggest two major concerns with the income tax mobilisation drive. First, while the effort to bring more people into the income tax net is laudable, the productivity in terms of impact on revenue yields has been small. Second, the stagnant or declining nominal yield per taxpayer suggests that tax returns are not able to capture the tax benefits of the growth of personal income at a time where the economy is highly buoyant and there is evidence of a growing concentration of personal income from HIES data. The evidence would seem to support the contentions of two populist perceptions: first, that the tax net is focused on capturing low-income taxpayers while many large-income earners remain outside the net; and second, the large-income taxpayers that enter the net end up paying low amounts through collusion with income tax collectors.

Tax evasion is an outcome of three major factors. First, according to the Labor Force Survey of 2017, some 85% of the workforce is in the informal sector and most workers are outside the tax net. Second, most of the rich elites are well connected with the government in power and are able to escape taxes, either by not filing or by sending in low returns that are not subject to audits owing to the political connection. Third, it is well known that many taxpayers are able to get away with low returns by making informal deals with tax collectors. The manual approach to tax assessment makes this process so much easier.

A serious problem with tax administration in Bangladesh is the complexity of the tax collection process and the harassment of the tax payer. Tax filing is not user-friendly, simple, or automated. One example of a bad feature of the present tax design that discourages tax filing and leads to harassment and corruption is the requirement to file a wealth statement based on balancing income and expenditure along with the tax return. Many taxpayers find this requirement onerous and it discourages them from filing taxes because of the fear that this will lead them to experience various forms of harassment. It also encroaches on citizens’ privacy. While the Government has the right to tax income, it is debatable whether citizens should be required to explain how they spend their money.

The value of this dubious requirement in terms of tax collection is negligible and on a net basis negative because it discourages tax filing. Importantly, there is a common perception that this feature creates incentives for income tax officers to harass taxpayers and extract a bribe. As an example, income tax collections and compliance are very high in the USA, where there is no such requirement to submit a wealth statement based on a matching of income and expenditure. On the negative side, in Bangladesh, the returns from personal income taxes as a share of GDP have hardly grown over the eight years from FY2010 to FY2018, despite a near doubling of real per capita income in dollar terms. It is obvious that the wealth and income expenditure statements have not helped increase revenues but have tended to support revenue leakages through non-filing and collusion between taxpayers and tax collectors.

2 Corporate Taxation

In the case of corporate taxes, similar problems exist as for income taxes. Most small enterprises are not registered and therefore are not a part of the tax net. Even for firms that are registered, the compliance rate is only 21% (Ahmed, Reference Ahmed2019). The low compliance rates reflect a combination of political power of many business houses that are well connected with the Government, and informal settlements between companies and tax officials. The corporate tax rates vary considerably by activities. There is a zero rate for many sectors or activities that are either exempted from taxes or have been given tax holidays for a number of years. Positive rates range from a low of 15% to a high of 45%. The NBR has targeted a few cash cows and slapped them with high tax rates: tobacco (45%); mobile telephone companies (40%); and banks and insurance companies (40–42.5%). Tobacco and mobile telephone companies are already heavily taxed through the excise, customs duties, and VAT instruments. Every year during the formulation of the annual budget, there is extra scrutiny to determine how much additional revenues can be extracted from these companies either through corporate taxation or by taxing their inputs. There is very little analysis to understand the implications of the existing corporate tax structure on incentives, including for foreign direct investments. Tax administration is cumbersome and time-consuming. The burdensome nature of tax filing has been identified as a major factor for the high-cost nature of doing business in Bangladesh, and as a constraint on improving the investment climate (Ahmed, Reference Ahmed2017).

An added problem is the large informal economy. Most small and micro enterprises escape the tax net because they operate outside the formal system and are not registered with the Government, either through business licences or through a tax identification number. The fear of taxation in terms of harassment is so large that small firms prefer to stay informal and forgo many benefits of government support programmes, including access to formal credit. In this regard, the tax system may work as an important deterrent to the growth of small enterprises and employment.

3 Implementation of the VAT

Problems of tax administration are also acute in the case of the VAT. The many exemptions and the inability to extend the VAT fully to the retail level, many services and to small and micro enterprises, along with evasion and tax administration inefficiencies, have sharply lowered the productivity of the VAT (Mansur et al., Reference Mansur, Yunus and Nandi2011; Ahmed, Reference Ahmed2013). Even for firms that are registered, the compliance rate is estimated at 12% (Ahmed, Reference Ahmed2019). The present VAT system is very inefficient and is characterised by low productivity. Cross-country comparisons show that this productivity is among the lowest when Bangladesh is compared with Thailand, Vietnam, Sri Lanka, Nepal, India, China, Indonesia, Philippines, and Pakistan (Mansur et al., Reference Mansur, Yunus and Nandi2011). The factors that contribute to this low productivity include multiple rates, large exemptions, tax evasion, and inefficiencies in VAT administration. These administrative inefficiencies include: cumbersome tax filing; absence of a centralised registration system leading to multiple registration; a weak and burdensome audit system; and the lack of a modern computerised VAT system (Mansur et al., Reference Mansur, Yunus and Nandi2011; Ahmed, Reference Ahmed2013).

As noted earlier, in recognition of these difficulties, and prodded by the IMF, in 2012 the Government enacted the new VAT Law. The Law simplified and modernised the VAT, along with provisions for major improvements in VAT administration, including a shift from manual to electronic filing, a voluntary approach to tax compliance, broadening of the tax base, a single registration for each taxpayer, the use of the invoice credit method for tax assessment, and a simplified VAT refund system (Ahmed, Reference Ahmed2013). Substantial technical assistance was arranged to prepare for the implementation of the new law. Between 2013 and 2017, good progress was made in preparing for the implementation. The draft budget for FY2017/FY2018 was prepared with a view to implementing the new VAT Law. But, as noted, the implementation was postponed on political grounds.

4 Implementation of Customs Duties

The implementation of taxes on international trade is more organised and better administered. Modernisation of the customs system started in 1994 with the adoption of the Automated System for Customs Data (ASYCUDA) of the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). Bangladesh has sought to follow through with the various updates of the ASYCUDA. Progress has also been made on import valuation. Several reforms have been implemented to speed up and simplify the customs clearance process, including rolling out the Authorised Economic Operator programme, initiating implementation of a National Single Window, the establishment of a National Enquiry Point, and the development of the Advance Ruling System. A new Customs Act is also being prepared. Nevertheless, many problems remain. On the revenue mobilisation side, the main problem is tax evasion based on collusive behaviour between importers and the customs staff. This is a governance challenge that permeates the tax administration. Additional issues emerge for private investment in terms of high transaction costs of doing business at ports. Despite progress in simplifying clearance procedures and valuation, the transaction costs remain high, as indicated by the World Bank’s Ease of Doling Business indicators.

5 Tax Administration Capacity

A generic problem in tax administration is low tax capacity. The NBR lacks autonomy and is run like any other government department; it is staffed by civil servants. Its primary focus is tax collection through policing and threats: there is no concept of tax service or seeking voluntary compliance through user-friendly approaches.

There is very little capacity to undertake tax policy analysis (PRI, 2013). Tax changes are made in almost all budgets. There is little analysis of the revenue and resource allocation impact of these changes. This lack of separation of tax policy and tax collection, and the absence of capacity of the NBR to implement proper tax policy and analysis, is a severe institutional constraint that has hurt fiscal policy development.

Numerous efforts to upgrade the capacity of the NBR to improve tax collection and tax policy analysis have failed owing to a lack of political and administrative support (PRI, 2013). In situations where a reform-minded NBR chairman has sought to bring about tax administration changes, this has failed because the chairman was replaced before implementation could begin. Frequent changes at the top (chairman NBR) have further reduced the ability to reform NBR.

6 Summary of Institutional Constraints: Weak State Fiscal Capacity

The picture that emerges of the taxation system of Bangladesh is of a system that is characterised by informality; negotiated settlements by elites; a highly complex, non-transparent and discretion-based system; a manually run and weak tax administration; low compliance; corrupt practices; and low accountability. The end result is a highly inefficient, corrupt, and low-yield tax system. The political economy tax literature recognises this as an indication of weak state fiscal capacity.Footnote 4 The basic argument is that the reason why rich countries have a considerably higher average tax to GDP ratio is because they have invested successively in their fiscal capacities over a long period of time. This higher fiscal capacity is reflected in much greater reliance on modern tax bases like income and VAT, as well as much better ability to enforce tax compliance. By contrast, low-income developing countries have weak state fiscal capacity that sharply reduces VAT and income tax compliance, and therefore their ability to raise adequate fiscal resources. To increase tax revenues, a low-income country will need to invest in institutions that increase the state fiscal capacity. Within developing countries, there are differences in the degree of weakness of state fiscal capacity, some being relatively stronger than others and hence having relatively better ability to mobilise fiscal revenues than others. In this framework, Bangladesh falls into the list of countries that have among the weakest state fiscal capacity.

The specific areas of capacity building required will vary from country to country, but some generic areas that could help build state fiscal capacity include: strengthening the legal framework to enforce contracts; the establishment of property rights; strengthening the rule of law; facilitating the growth of democratic institutions; growth of the financial sector; and strengthening of the tax administration. Thus, state fiscal capacity is a combination of political institutions, economic institutions, and administrative institutions. Progress in any of these three areas will help increase state fiscal capacity and contribute to increasing revenues. The development of political institutions is a tough challenge and will likely evolve over a longer period of time, but investments in economic and administrative institutions hold greater promise for progress in the medium term.

VII The Way Forward

Summarising his views on the lessons of international experience with tax reforms, noted tax expert Richard Bird writes: ‘Fifty years of experience tells us that the right game for tax researchers is not the short-term political game in which policy decisions are made. Academic researchers and outside agencies interested in fostering better sustainable tax systems in developing countries will employ their efforts and resources most usefully if they play in the right game. That game is the long-term one of building up the institutional capacity both within and outside governments to articulate relevant ideas for change, to collect and analyse relevant data, and of course to assess and criticize the effects of such changes as are made. Tax researchers, especially in developing countries themselves, can and should play an active role in all these activities’ (Bird, Reference Bird2015). While tax reforms and tax institutional capacity building are indeed long-term endeavours, the fact that Bangladesh is a negative outlier in terms of the very low tax to GDP ratio when compared with countries at similar per capita income levels suggests that there is scope for progress even in the short term, through some relatively simple tax administration improvements.

A pertinent question to ask is, if tax reforms and administration improvements did not happen in the past why would they happen now? The answer to this question lies in the fact that the awareness at the highest political level of the need for some immediate minimum tax reforms is growing in Bangladesh. This is partly due to the emergence of an increasingly constrained fiscal space that is limiting the capacity of the Government to deliver even basic services at the same time that demand for these services are growing and expectations are building up. The successful implementation of the Government’s development strategy has accelerated GDP growth and improved human development and poverty outcomes. To keep the support of the people, the Government is now aspiring to reach greater development heights. It has adopted a new development vision, called the Vision 2041, and has converted this into a new development strategy, PP2041. The vision calls for Bangladesh to secure upper middle-income status (World Bank Atlas method) by FY2031, and high-income status by FY2041. Vision 2041 was an integral part of the Government’s 2018 election manifesto.

The Government’s own macroeconomic framework for PP2041 shows that the targets to reach upper middle-income status and eliminate extreme poverty by FY2031 require a doubling of the tax to GDP ratio over the next 12 years. Also, as articulated in PP2041, the Government agrees that the main focus of tax reforms should be to raise the revenue base for income and consumption taxes, while reducing reliance on trade taxes, in order to eliminate the anti-export bias of trade protection.

To show its concern about poor revenue performance and signal its intention to follow the PP2041 fiscal path, the Government put forth an ambitious target of raising the tax to GDP ratio by 3 percentage points in the FY2020 budget. However, as noted, this ambitious tax target was not adequately backed by policy actions. The new Finance Minister was probably not fully aware of the complexities and inherent weaknesses of the tax system. Independent research by fiscal policy experts and associated public debate on the need for credible tax reforms has set the stage for some constructive discussions about what might constitute some helpful and achievable tax administration reforms over the next few years as steps towards achieving the tax targets of PP2041. These reforms are based on the lessons from international experience, as well as experience from Bangladesh. The Government is now open to greater and more meaningful consultation with independent researchers on the type of tax reforms needed to achieve the PP2041 fiscal targets. This is an important development and consistent with Richard Bird’s observation noted above concerning the positive role of independent tax research and policy debate in furthering the case for tax reforms.

A Tax Institutional Reforms

Consistent with the analysis of weak state fiscal capacity, some minimum institutional reforms are essential to see any systematic progress with tax revenue effort. These include the following:

1. Separation of tax policy from tax collection: An essential institutional reform is to separate tax policy from tax collection. Although the NBR is entrusted with both tax policy and tax collection, it de facto serves as a tax collection entity. While it has senior tax policy staff, the overwhelming focus is on tax collection. This single-minded focus on tax collection has come into serious conflict with the design of a broad-based tax policy that is consistent with revenue goals, ensures the efficiency of tax collection, and avoids adverse implications for incentives and national resource allocation. It also explains the ad hoc nature of tax policy during the annual budget cycle, where the focus of tax policy is on raising revenues to meet the budget target, without regard to the impact of the tax measure on resource allocation or efficiency. A better arrangement would be to assign the NBR the primary responsibility for collecting taxes and giving tax policy responsibility to either a special unit within the Internal Resource Division or to the Budget Division of the Ministry of Finance. The advantage of assigning this to the Budget Division is that this entity has substantial macroeconomic policy analysis capabilities. It also has the responsibility for developing the medium-term budgetary framework and the annual budgets. These provide the Budget Division with considerable knowledge and stronger capabilities to formulate tax policies than the NBR or the Internal Revenues Division.

2. Strengthening tax policy and tax collection agencies: Whatever institutional arrangements the Government may adopt, both tax policy and tax collection efforts have to be substantially strengthened through the induction of better professional staff. The Government has considerably increased civil service salaries in recent years, which has improved incentives for professional staff to apply for public service positions. The tax departments (the NBR and the tax policy unit) need a much stronger combination of professional staff with civil service staff. If needed, some additional incentives could be provided to attract fixed-term tax professional experts to the Ministry of Finance. This small investment in tax administration capacity would have a high rate of return in terms of better tax policy and revenue performance.

3. Selection and tenure of the NBR chairman: The frequency of changes of the NBR chairman has a serious negative impact on tax collection. The Government might want to delink the position from the civil service, select the chairman on a professional basis, and establish a minimum tenure of four to five years. This will strengthen the quality of tax administration leadership, de-politicise this position, and provide stability and an incentive for the chairman to take tough actions against corrupt practices.

4. Fully digitising the tax administration: Consistent with the policy of the prime minister to rapidly adopt online technology as the primary mode of transactions with the Government, full digitisation of the tax administration is of the highest priority. Some progress has been made for the customs and VAT administration, but there is a long way to go, especially for income tax administration. Full digitisation of tax administration, especially personal income taxation, will go a long way towards reducing corruption, increasing compliance, and increasing tax revenues.

5. Strengthening the budget consultation process: The Government already has a healthy consultation process involving the citizens. This should continue. However, the participation of the Cabinet and the Parliament could be strengthened considerably. The Cabinet review of the draft budget could be made more productive by requiring each Cabinet minister to make a presentation on their development targets and objectives for the year, and to discuss the adequacy of the proposed resource allocation to secure them. This process could be very useful in bringing out the internal tensions and the challenges posed by the revenue constraints upfront, so as to allow proper policy choices to be made, including the need for meaningfully strengthening revenue mobilisation. Regarding the Parliament, one possible option is to involve the appropriate Parliamentary Committee responsible for oversight of budget and finance issues early in the process of budget making, to get timely inputs into the process.

6. Promote fiscal decentralisation: Greater fiscal decentralisation could help mobilise revenues by providing a better link between service delivery and accountability. The Government has made some progress with administrative decentralisation by instituting a system of elected local government institutions. The next step is to assign clear service delivery responsibilities without overlap with competing national entities, build local government institution service delivery capacities, and institute a well thought out fiscal decentralisation system.

B Reform of the VAT

The proposed reform of the VAT leading to the VAT Law of 2012 was sound. Technical assistance to help with implementation had also progressed well. It is most unfortunate that this progress was ignored by the new government and a hodgepodge VAT reform was introduced in the FY2020 budget. As most tax experts familiar with the Bangladesh VAT system agree, the FY2020 VAT reform will likely not work. The Government is hesitant to accept this view and is bent on implementing the modifications to the VAT system it introduced in the FY2020 budget. It is hoped that the implementation experience with the VAT modifications of the FY2020 budget will provide good evidence of its limitations and the need to revert back to the provisions of the 2012 VAT Law. This hopefully can set the stage for the implementation of a solid VAT reform in the FY2021 budget.

C Reform of Income Taxation

Notwithstanding all the caveats associated with political and administrative constraints on income tax collection, it is high time that the Government made a serious effort to reform the income taxation regime, especially as it seeks to achieve upper middle-income tax status.

D Corporate Taxation

Several actions can be taken in regard to corporation taxation, including streamlining the corporate tax rate in a series of steps. As a first step, with the exception of tobacco, the maximum rate of taxation should be lowered, starting with 30% in FY2021 and 25% in FY2022. As rates come down, exemptions and tax holidays for foreign direct investment or specific sectors must be eliminated over a well-defined period, so that by and large all investors are required to pay taxes. Once the tax rates are lowered and made internationally attractive, exemptions will not be needed. Capital flight for taxation purposes will not be an issue because the investor will have to pay taxes in other countries as well.

E Personal Income Taxation

The personal income reform needs a substantial overhaul based on further research and analysis. The reform that is required is to lower the marginal and average tax rates and to increase the tax base through voluntary compliance. Bangladesh can learn the lessons from the positive experience with income taxation from other countries. These lessons include the following:

The best approach to increasing the tax base is to provide incentives for voluntary compliance. Having large marginal tax rates and putting pressure on those who pay is a recipe for disaster. It is like killing the goose that lays the golden eggs. Many taxpayers will find ways to escape the tax net by entering into collusive behaviour with the tax collectors, as presently.

The tax system must be based on the principles of universal income, self-assessment, and productive and selective audits. It must be fully digitised wherever possible, with no interface between the taxpayer and tax collector, except when subject to audits.

The tax system must be simple, with a low compliance cost. Indeed, the simpler the system and the lower the tax rates, the more likely it is that there will be voluntary compliance and the less the scope for tax harassment and corruption.

The audit system should be highly selective and productive. The objective of the audit system should be to discourage tax avoidance and not serve as an instrument of harassment or to extract a bribe. The audit system should be based on a computer-driven model developed on the basis of well-identified criteria that, if violated, would trigger an audit. The criteria must make the audit productive so that the collection cost is only a fraction of the total taxes raised through audits. It should be highly selective, with no more than 5% of returns audited systematically.

The attitude of the NBR should change from tax ‘policing and harassment’ to voluntary tax compliance based on a user-friendly and tax service approach.

Self-assessment, digitisation, and simplification of personal income tax filing with a user-friendly and service-oriented approach will vastly increase tax compliance and tax collections, as reflected in the experience of countries with good income tax collection records.

F Property Taxation

Most upper middle-income and high-income economies have a well-established system of fiscal decentralisation whereby the property taxes are assigned to local governments as the major source of tax revenues. In Bangladesh, such a political decision on fiscal decentralisation has yet to happen, although it is imminent as Bangladesh aspires to attain upper middle-income status. Indeed, the PP2041 puts considerable emphasis on the need for fiscal decentralisation. The next step is the political debate and buy-in at the top level.

In the interim, the Government should design and implement a modern property tax system that is different from the present fragmented two-part system whereby the NBR collects a wealth tax as a part of the income tax and local governments collect some nominal taxes on properties. A modern property tax that is based on the true market value of properties and evaluated and updated systematically using a computerised property ownership database is an essential element of a modern tax system. There are many models of a well-designed property tax system that can be researched and implemented in the specific political economy context of Bangladesh. Implementation can proceed in a phased manner, starting with the capital city of Dhaka and then extended to other divisional cities and finally to all urban areas.

G Reform of the Customs System

Recognising the continued high cost of customs administration and its adverse effects on trade logistics and private investment, the NBR has recently developed and adopted a new customs reform programme known as the Customs Modernisation Strategic Action Plan 2019–2022 (NBR, 2019). This is a comprehensive and ambitious endeavour that seeks to improve the efficiency of the customs system and reduce the transaction costs related to international trade. Tariff rationalisation is also an objective, although the end game of tariff rationalisation (reduction of trade protection) is less clear. Nevertheless, this is a welcome initiative and its sound implementation should be a high policy priority.

Annex 6.1 Import Duty–Related Sros Fy2015–Fy2019

| CPC | Description | Purpose | Beneficiary |

|---|---|---|---|

| 135 | Car/Micro Bus imported by industrial unit of EPZ | Special exemption for imports of cars/jeeps | EPZ industries |

| 137 | Car/Jeep imported by MP’s | Special exemption for imports of cars/jeeps | Members of Parliament (MPs) |

| 140 | Generator Assembling Plant, SRO 80/2007, CD 0% | LP gas cylinder manufacturers | LP gas manufacturers |

| 148 | AIT exempted for warehouse | Special exemption benefit | Special benefit to certain groups |

| 156 | Poultry Accessories, SRO-158/2004, CD, SD, & VAT exempted | Special benefit for poultry firms | Poultry sector |

| 157 | Textile, SRO-157/2004 (Table-I, CD, SD, VAT exempted & Table-II, CD 7.5%) | Textile machinery and parts | Textile sector |

| 159 | Leather, SRO-169/2005, CD 7.5% | Special benefit to raw materials for leather sector | Leather sector |