E. Morin developed thinking on how important it is for the social sciences to study crises.Footnote 1 In particular, he showed that a crisis of endogenous origin reveals the tensions and contradictions in a social system that led to the crisis occurring – that determined it from within. Also, beyond its analysis (its course, its eventual means of resolution, its consequences), studying an endogenous crisis helps better understand the social system in which it occurs.

The book in which this chapter appears aims to develop thinking on management education institutions facing the COVID-19 crisis.

The question of the relevance of this thinking arises immediately; the COVID-19 crisis is, first and foremost, a public health crisis. There is little doubt that it has had consequences on many other spheres, including that of management education. But what can we learn for this sector from a crisis imported from another sector? It seems logical to assume that management education institutions reacted to this crisis by trying to operate as closely and consistently to the way they had been accustomed to operating before the crisis period. Studying such a situation makes it possible to better understand how the management education sector reacts to a crisis of exogenous origin. But to what extent can this tell us about the dynamics of the sector in question? A review of the very notion of crisis clearly shows the potential for developing such thinking.

The COVID-19 Crisis Reveals the Social Role of Business Schools

The expressions commonly heard in everyday language at the time of a crisis such as that of COVID-19 (“return to normality,” “the new normal after the crisis,” etc.) demonstrate the extent to which the very notion of crisis is strongly linked to that of “normal” and “normality.” G. Canguilhelm approached the latter notion as consubstantial with that of abnormality, but above all, he highlighted the extent to which the normal is understood in relation to the implementation of a project

The abnormal, as ab-normal, comes after the definition of the normal, it is its logical negation…. The normal is the effect obtained by the execution of the normative project, it is the norm exhibited in the fact.

Thus, the notion of crisis describes a situation in which it seems as though one has left a situation of normality in which a project was being implemented.

The importance that one gives to the latter results in a will to return to normality (and is thus a “crisis project,” the existence of which implies a “crisis strategy” that one tries to carry out in parallel to the project that justifies an organization’s existence) and therefore to the previous situation. However, the realization of a crisis project can ultimately assert itself not as leading to the status quo ante but as revealing new possibilities to be implemented (Habermas, Reference Habermas1976). If an endogenous crisis provides information on the weaknesses of the past, the study of a crisis of exogenous origin makes it possible to analyze potentialities for the future.

These two attitudes – that of seeking a return to the previous situation and that of developing new ideas and their implementation – emerge from the examination of the strategies and actions of business schools in the face of the COVID-19 crisis. The analysis of this crisis makes it possible to appreciate the depth of the changes underway in management education and confirms Milton Friedman’s assertion that “only a crisis – actual or perceived – produces real change” (Friedman, Reference Fox1962/2002, p. xiv).

In other words, the study of the influence of the COVID-19 crisis on management education institutions leads not only to studying the way in which these institutions are organized in order to be able to continue to develop their management education but also, beyond management education, how they were able to structure themselves so as to help solve the constitutive social crisis which is that of public health.

Studying how management education institutions have responded to the COVID-19 crisis helps to shed light on how they see their mission.

Responsiveness to the Crisis in the Management Education Sector

Although some management education institutions had begun, as early as the start of 2020, to develop their thinking on how to react to the pandemic, the consequences of this did not really erupt into the management of business schools, except for those located in the Wuhan region, until February and March. Then, in management education institutions around the world, it suddenly became a question of responding to very concrete challenges. Examination centers being closed, it was impossible to take the Graduate Management Admission Test (GMAT) and the Graduate Record Examination (GRE) in China, and it very quickly became so in Bahrain, Mongolia, Kuwait, Thailand, Hong Kong, Singapore, and other places as well. It became necessary to cancel study trips and seminars in China even though “global experience,” “immersion trip,” “global consulting,” and other such programs in which social-impact projects constituted a significant feature had been rapidly increasing in the country. In a now-globalized management education market in which Chinese students represent a very large proportion of international students, we observed a drastic decrease in international applications for the following academic year.

Very quickly, too, immediate daily management problems arose as a result of the consequences of the epidemic that was taking hold across the world. Thus, institutions in Europe and Asia (quickly followed by those in certain regions of Oceania and Africa) had to face confinement as of March. At this time, when the United States was not yet intensely affected by the epidemic, the first effects of it were being felt on campuses (e.g., starting at the very end of February at Tuck School of Business, after a student came in contact with a patient during an on-campus party, Dartmouth College had to deal with the first effects of quarantine). In addition, management schools and faculties have had to tackle major reorganization and rescheduling issues.

The way in which schools reacted to the occurrence of a crisis is very revealing, both of their management style and of their position in the societies in which they operate. It is particularly remarkable that in Europe, Asia, and South America (and a little less in the USA), schools anticipated the measures taken by their regional and national political and administrative authorities. The examples are too numerous to all be cited, but we can present a few from various continents.

On March 12, a day after the outbreak was declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization, 16 cases of COVID-19 were reported among Mexico’s 128 million people. Although the number of cases was still very low in the country at this date, the IPADE Business School, sensitive to the global impact of the coronavirus, decided the next morning to temporarily suspend face-to-face activities in all of its national and international academic programs to protect the health and integrity of every member of its community. With the firm conviction that everyone must take part in the fight against the spread of the virus, IPADE implemented this precautionary measure even before the Mexican Ministry of Education decided to suspend all educational activities in the country (Alvarado and Romero, Reference Alvarado and Romero2020).

At the Gordon Institute of Business Science at the University of Pretoria on March 16, all face-to-face teaching had ceased, and the bulk of employees had begun to work from home (Kleyn, Reference Kleyn2020; while the first case of coronavirus detected in South Africa dated March 5, when there were in all only 27 cases in the whole of Africa). This decision long preceded the first measures taken by the South African government.

The Hong Kong University of Science and Technology was an even more specific case because, as a result of the troubled situation in Hong Kong, which had led some students to move away from campus, the school had been operating with hybrid teaching since fall 2019.

Grenoble Ecole de Management (GEM) decided to put an end to two essential activities – face-to-face teaching and work at school – 72 hours before the French government decided to initiate a national confinement strategy (Saviotti, Reference Saviotti2020). The reasons for this reactivity are extremely revealing of the reality of business school activities: at the end of December 2019 and in the beginning of January 2020, GEM received feedback from exchange students in Asia and on its campus in Singapore indicating the development of a difficult situation. Thanks to the quality of this dialogue that arose as a result of the internationalization of its activities, GEM had started to prepare itself to face a major crisis. In February, the school banned travel to China for its students and staff and asked all staff and students in the country to return to their home countries.

These few examples were chosen arbitrarily from dozens of similar ones. They trace how the international activities of business schools helped found their crisis management and how they are in a position to coordinate their decisions with those of national administrations. These examples are all clues to the way in which business schools now connect a regional and national dimension to an international one.

Adapting Schools’ Activity to Maintain Their Raison d’être

In general, the first responses of schools to the onset of the coronavirus crisis were situated in a reactive logic and centered around two priorities. These were, first of all, maintaining (or restoring, in the cases of institutions that had stopped teaching for a short period) their teaching activity as regularly as possible while also maintaining its quality (keeping in mind that they very quickly moved toward distance learning) and, second, recruiting students for the following academic year. (The globalization of management education had made it possible, for example, that even though in March the United States was still relatively unaffected by the coronavirus, business schools were already beginning to postpone the dates of their admissions rounds.)

The reactive attitude initially implemented by management education institutions is therefore typical of crisis logic; it involved maintaining, through a series of detailed responses to organizational needs and specific dysfunctions, operations that were as close as possible to those in effect in the “normal” situation before the crisis.

Although it was accepted that logistical and educational adjustments were necessary (caused in particular by the switch to distance education), these were not to affect the logic and the deep coherence of the system of management education. The objective of management education institutions seemed to consist of getting through the difficult moment of crisis, getting out of this abnormal situation, and returning to a normal one by perpetuating the main modes of operation and the logic of the system.

However, clues quickly appeared that made it possible to measure how difficult such an approach would be. An episode in the life of business schools that took place in March and April is a particularly revealing example of this difficulty. The high tuition fees at business schools are, particularly in the United States, a constituent element of the system. Talented candidates who have already accumulated significant savings or a high borrowing capacity as a result of their prior professional careers and the resulting social recognition are admitted to business schools following a strict selection process. There, they receive an education that subsequently enables them to accelerate their careers and increase their income (and thus to reimburse, if necessary, the very high cost of their studies). The quality and relevance of this education constitute the supreme justification for its high cost because they guarantee that the system functions properly.

It is thus very interesting that starting in the second part of March, in many business schools, including some of the most prestigious, a petition signed by a very large proportion of students (for example, 80 percent of students at the Stanford Graduate School of Business) demanded that the management of their school reimburse part of the tuition fees to students during their schooling because of the switch to distance education (Moules, J., Reference Moules2020, April 12). These petitions particularly affected American universities (e.g., the Stanford Graduate School of Business; the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania; Columbia Business School; the University of California, Los Angeles [UCLA] Anderson School of Management; the New York University [NYU] Stern School of Business) but also schools beyond the United States, for example, in Europe (IE Business School in Spain) and in Canada (University of British Columbia [UBC] Sauder School of Business).

The signatories of the petition justified their request with two main elements: first, they presented distance education as being of inferior quality, and second, they argued that the tuition fees paid to schools cover not only the education provided but also campus life – the latter being a socialization process that includes starting a networking process for their future professional careers, both with the leaders and professionals with whom they might make contact through campus life and with the other students, who will later develop their own careers.

Switching to distance learning during an epidemic appears to be a logical and appropriate reaction; however, this change has had consequences on the operating logic of schools.

This episode has made it possible to measure the danger of a solely reactive approach that responds step by step to the difficulties caused by the COVID-19 epidemic and dispenses with a substantial reassessment of the practice and of the approach implemented. Such an approach risks losing the coherence of the functioning and activities of schools.

The pandemic presents some unique challenges to business schools because of their international character. Numerous business schools have experienced students and staff from a range of countries being forced to return to their home countries because of travel or visa restrictions (Krishnamurthy, Reference Krishnamurthy2020, p. 3). The top 20 MBA programs in the United States reported a 14 percent decline in the number of international students: compared to the fact that international students account for an average of 35 percent of students in elite programs, this indicates the magnitude of the challenge that COVID-19 poses to business schools. These students in the USA have the distinction of paying full tuition fees, which can be as high as $160,000 per year (Roth, Reference Roth2020).

In many business schools, foreign students are an important source of income because they subsidize the tuition fees of domestic students (Brammer and Clark, Reference Brammer and Clark2020, p. 453). As the number of foreign students declines, institutions may be forced to change their financial models. Moreover, institutionally, many business schools are now part of universities, whose entire business model is threatened by the pandemic.

Moreover, the mere fact that COVID-19 has had a significant impact on business has profoundly affected business schools. Entire sectors, such as aviation and tourism, have been severely affected, without any prediction of when or even if an upturn will occur. Similarly, small and medium-sized enterprises are often in a particularly unstable situation and are threatened with bankruptcy. This will have an impact on the opportunities for students after their studies and thus on the academic paths followed and the curricula. At the same time, there is a growing interest in health-care management (Krishnamurthy, Reference Krishnamurthy2020, p. 4).

These changes, as well as the labor-market volatility that graduates will face in the coming years, are expected to have an impact on enrollments. But these changes are also having an impact within schools themselves: a survey of 172 senior university executives indicates that their main short-term concerns have been identified as the mental health and well-being of students and staff, unbudgeted costs, and high dropout rates. In the long term, their main concerns are about the financial future of their institutions.

Alongside the various challenges to be overcome, it is interesting to point out that the current crisis has also created opportunities. The demand for flexibility and adaptability has led to a significant acceleration of innovation in the academic world, which may generate opportunities to reimagine the future of resilient and sustainable academic institutions. Previous research carried out before the coronavirus crisis indicates that students study slightly better online than in a traditional classroom environment, indicating the possible benefits of moving to e-learning (Krishnamurthy, Reference Krishnamurthy2020, p. 2).

In addition, teaching staff members have proven their resilience and adaptability, committing themselves to research and teaching throughout the crisis. Communication channels, as well as teaching and assessment methods, have been reimagined. A major challenge faced by business schools is continuity of teaching, mainly through a focus on the continued availability of educational opportunities for the students during disruption. Business schools strive to make arrangements to provide students with education during this period. Emphasis is placed on finding a way to maintain services during the disruption period. During this period, business schools undertake “emergency distance education,” with a focus on sustaining curriculum requirements (Hodges et al., Reference Hodges, Moore, Lockee, Trust and Bond2020). At the institutional level, the consolidation of technology as a central aspect of higher education offers various opportunities for collaboration and even restructuring of academic institutions. The crisis has also accelerated and intensified existing trends, providing the conditions for a natural experiment in which adaptable institutions can test innovative methods and practices. It has also opened up opportunities for new areas of research on changes in consumption, communication, and market trends, as well as on adaptive and innovative capacities in times of international crisis.

Emergent Strategy and the Need to Maintain Consistency in the Face of the Crisis

Our purpose is certainly not to argue that the community of management education institutions has contented itself with being reactive to the coronavirus crisis. Not only have strategies to respond to the effects of the crisis (see the crisis strategies mentioned previously) been implemented, but so have strategies involving fundamental changes whose relevance became apparent during the crisis.

If strategy is defined as a pattern in a stream of decisions and can be conceived as a continuum going from deliberate to emergent strategies (Mintzberg and Waters, Reference Mintzberg and Waters1985), the latter can be defined as “patterns realized despite or in the absence of intentions” (Mintzberg, Reference Mintzberg1979, p. 257).

The notion of emergent strategy reflects the way in which strategies have been developed in business schools in the face of the situation created by the coronavirus. Although the decisions taken were made in response to given challenges, it is possible to highlight a consistency between these decisions that creates a strategic pattern. The implementation of an emergent strategy requires that the actors in organizations have developed sufficient empirical knowledge and practical wisdom forged in the field to allow them to make decisions that are compatible with the needs of the context. That is, they need to have a clear understanding of what it is possible to do and the consequences of making a decision. The notion of emergent strategy does not imply that the decisions taken within this framework are secondary decisions, whereas the important decisions are only the subject of deliberate strategies. The culture; the type of staff working for business schools; the balance between administrative and academic staff; and the presence, in many cases, of very committed leadership have led to the implementation of emergent strategies that go well beyond the blow-by-blow response of reactive decisions.

The question of selection tests, which is a central issue for business schools, is an example of how elements of emergent strategy have been formed. On the one hand, this question models the type of candidates, and therefore the students, that the school receives and thus, consequently, the character of the school. Moreover, to the extent that these tests require a great deal of preparation, they create expectations commensurate with the level of “suffering” they have generated in test-takers. At the same time, experience shows that the effort that students feel they had to make to be accepted is strongly correlated with their level of identification with their schools. In addition, the GMAT and GRE score requirements contribute to determining the schools’ reputations.

Lastly, and above all, because these tests are deemed reliable, they constitute an important “safety net” for schools by guaranteeing the quality of candidates in a certain number of parameters considered fundamental. Even if the GMAT and the GRE are sometimes criticized because they produce too homogeneous a profile of students, giving them up is a difficult choice for the schools. In addition, these tests have demonstrated their undeniable quality over the years, and moreover, they have demonstrated their ability to evolve and improve with respect to all the challenges they have to face.

Additionally, most of the schools, in particular, most among the more recognized ones, had retained a GMAT or GRE requirement for candidates until extremely recently. We must therefore consider the current trend to exempt GMAT and GRE at its proper importance.

Following the June decision by the University of Virginia Darden to waive these tests, other universities made the same decision in August and September (Wisconsin School of Business, Rutgers Business School, Northeastern University Kellogg School, University of Texas at Austin McCombs School of Business, Emory University Goizueta Business School). The consequences of these exemption decisions were not long in coming. For example, in mid-July, Darden announced an increase in MBA applications of 364 percent (Byrne, Reference Byrne2020c).

The rationale put forward for these exemptions is that during the coronavirus epidemic, it was very difficult for applicants to be able to take the GMAT and GRE tests within a reasonable timeframe. The decision was based on the observation that it was impossible to continually push back the deadline for submitting applications. At one point in the process, universities also feared that they might face a shortage of applicants (which may explain, for example, why Northwestern Kellogg, alongside granting test waivers, also decided to revisit rejected applications).

But now Pandora’s box has been opened. It is indeed difficult to think that after the eventual end of the epidemic, a return to the status quo ante in the selection process will be entirely possible. At the same time, no one can seriously imagine that this change will not have profound consequences for management education institutions. Indeed, this should upset the type of preparation done and change the level of investment in time and money in order to be a candidate. Schools will certainly not be satisfied with using the same selection process with one less evaluation parameter (the tests); they will have to completely rethink their selection process and take career profiles into account more.

Yet while some argue that this could give applicants from low-income families a greater chance of getting in (Byrne, Reference Byrne2020a), given the high cost of preparing for the GMAT and GRE tests, foregoing such a reliable and relevant tool does not appear to be an inevitable option. The Graduate Management Admission Council (GMAC), the company that designs these tests, has demonstrated its capacity for innovation and to face challenges that arise. Furthermore, one also imagines that GMAC will cooperate with the schools to limit the impact of the social environment of origin on the results of candidates’ tests. And without the tests, the assessment of applications from foreign applicants would be much more difficult because it is traditionally complicated to assess career profiles from distant countries; this could lead to a change in the composition of the groups recruited, and it would become necessary to modify the pedagogy during studies. The conditions of competition have also been disrupted; can one seriously imagine, for example, that being able to apply to Kellogg without having to take the GMAT or the GRE would not have a huge influence on candidates in Chicago (and therefore force this university to change its criteria, which would likely lead to the same at other institutions)?

Finally, it is difficult to think that schools have made such fundamental choices in terms of selection by imagining that it was only a question of solving a temporary, one-off problem and not of reacting to and participating in a systemic change.

Developing Comprehensive, Integrated Approaches to the Crisis

The fact that this example of a shift in the selection process seems to be a possibly favorable development should not lead one to infer that all developments provoked by the coronavirus crisis are easy and devoid of danger. We stand in opposition to the many articles published in recent months arguing that the chief among these developments (the spread of online education, exemption from GMAT and GRE tests, the increase in the level of admissions selectivity, authorization for deferrals of beginning of studies, etc.) are only accelerations of trends that began before the COVID-19 crisis and that, being “in line with the movement of history,” they are necessarily favorable.

We would like, on the contrary, to underline the difficulties that they carry with them, which attest to the fact that even if these developments were brewing and even if it was technically possible that they could be implemented, schools were careful not to spread them rapidly. They are only potentially favorable within the framework of approaches whose coherence we will present.

To highlight the issues, we will analyze a few examples of these supposedly fashionable developments that, in reality, were marginal before the COVID-19 crisis.

Even though online MBAs had experienced some development in recent years (Warwick, IE Business School, University of Massachusetts – Amherst, University of North Carolina [UNC] Kenan-Flagler Business School, Carnegie Mellon, Durham, Northeastern, Politecnico di Milano, Bradford, etc.), the majority of schools were careful not to rush toward this option.

The COVID-19 crisis has created a need to move toward this type of education. Examining the way in which schools have reacted to this imperative shows, however, that they have tried as much as possible to maintain outdoor or indoor teaching, at least in parallel to, and as much as possible side by side with, online education. Going online, if we want to combine it with quality education, requires significant investment, a fact that favors the most affluent and recognized schools. It is interesting to note that these have opted whenever possible for hybrid MBA education options rather than ones that are entirely online.

The approach adopted by INSEAD is indicative of schools’ preferences in terms of teaching during the COVID-19 crisis. At the same time, it is particularly remarkable for its coherence and the choices it entails.

Despite a 58 percent increase in MBA applications, INSEAD decided to reduce admissions on all its campuses by 38 percent in September 2020 in order to carefully manage social distancing guidelines and to organize all its MBA courses as face-to-face offerings (INSEAD, 2021). It is particularly noteworthy that this decision to conduct as much of the 2020–21 academic year as possible in an in-person setting was taken in consultation with students. It should also be noted that all courses will also be accessible by distance learning, making INSEAD’s approach a hybrid method with a preference for a classroom-based approach.

Similarly, at the beginning of July 2020, Harvard announced a move toward such a solution (at the cost of a reduction from 930 to 720 students in the entering MBA class) (Byrne, Reference Byrne2020b). Stanford is now moving toward an entirely online solution, as well, out of health necessity, specifying that if the situation vis-à-vis COVID-19 improves, its educational offerings will become hybrid. Even the institutions that have announced going online (Wharton; University of California, Berkeley, Haas School of Business; Georgetown; UNC’s Kenan-Flagler Business School; etc.) indicate that it is only to avoid remaining in limbo for too long a period and note that as soon as possible, things will change. Likewise, the case of Georgia Tech Scheller is interesting because after management announced that teaching would be partly on campus, the institution finally, reluctantly, gave up on the idea in early July. In fact, it was the teaching staff who drew the attention of the management to the fact that the state of health in Georgia did not allow for such a reopening. Management viewed maintaining education on campus as a strategic and educational priority but responsibly acquiesced to the public health argument.

The reasons for reservations with respect to a change that technically appears to be positive are not just a problem of resistance to change. They are also due to the fact that such a change cannot be conceived in isolation by ignoring the need for consistency with the many other parameters of school management. Some difficulties experienced at the end of summer 2020 by Wharton are an illustrative example of this.

Faced with the sustained increase in coronavirus cases, the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania announced on July 31 that it had changed its mind (Wharton School, 2020). It had previously announced (on July 6) that the fall semester would be hybrid but ultimately opted for a completely virtual semester. It also announced that it would not be flexible on matters of deferral of studies or discounts on tuition fees.

The school did not communicate clearly enough, claiming until July 21 by press release that the semester would be hybrid, and many students lamented that it was only after they had paid tuition and declined the offers of other schools they had been accepted into that this news was announced.

They also regretted that the particular case of foreign students was not taken into consideration. While the latter had planned to come to the United States on the basis of Wharton’s first indications of a hybrid semester, the sudden announcement that everything would be online put them in a difficult situation with respect to visas because the American administration is now making it difficult for students studying online to get them.

Students, management education professionals, and the press have thus insisted repeatedly on the poor management of the crisis at this eminent school.

Likewise, NYU Stern’s decision to increase its tuition fees by 3.5 percent (Joung, 2020), announced in early August 2020, appears to pose a problem of consistency and adequacy in the current situation. It is true that business schools traditionally increase their tuition fees every year. But not to see that this increase was acceptable only because it was based on the implicit double assumption that the quality of education improves from year to year and that salary expectations at the end of the MBA were increasing constituted a serious lack of lucidity. Also, in the period of transition to online learning, which is producing a lot of uncertainty, continuing to increase tuition fees constitutes a dangerous temptation and a lack of coherence in management, to which a number of the schools that have renounced such increases (Harvard, Chicago Booth, etc.) have not succumbed. Although it is understandable that NYU’s financial situation may require additional resources, to raise tuition fees (which prompted a petition from over 200 MBA students) is to omit the need for consistency.

Likewise, the manner in which Wharton switched to wholly online education risks damaging that school’s credibility. This shows that even in a crisis situation, it is necessary to take a holistic approach to managing change. In this case, the question of virtual versus face-to-face education was raised in ignorance of the fact that it is linked to many other parameters of school administration, in particular to the management of foreign students and the question of tuition fees and related issues.

The Harvard or INSEAD cases mentioned previously, on the contrary, would seem to demonstrate a comprehensive awareness of the situation. Indeed, the loss of approximately 200 students for Harvard’s 2020 entering class occurred because it was necessary to take into consideration the fact that a liberal policy in terms of deferral was needed, in particular for foreign students. (Harvard decided that any student, after having been accepted, could freely postpone their admission to the school by 2 years.) In addition, this choice can be explained by the decision-making logic holding that maintaining some amount of face-to-face education is very important and that, to that end, it was necessary to be able to follow the imperatives of public health and therefore initiate physical and social distancing among students.

The crisis situation places management education institutions in perilous contexts that are liable to jeopardize the future. Articles, books, and conferences devoted to the direction of academic management institutions in the face of the COVID-19 crisis that repeat that these adaptations constitute an opportunity, or that they validate favorable developments that had already been initiated and were ineluctable, call to mind the famous scene in Monty Python’s The Life of Brian in which convicts sentenced to death by crucifixion joyfully sing, “Always look on the bright side of life.” To accomplish their mission of training creative managers and agents of change and to maintain the sustainability of their institutions, the management of these establishments must develop global, integrated approaches, of which I have tried to give a few examples.

Business Schools: Social Actors in the Face of COVID-19

The elements analyzed previously show management education institutions that have responded to the COVID-19 crisis by attempting to create the conditions necessary to continue to accomplish their missions and fulfill their raison d’être by training students in management. In certain cases, the discussion has indicated how, in an effort of strategy and foresight, these institutions went even further by attempting to make the crisis an accelerator of change and a catalyst for improvements in the way they function. That these various shifts within schools tend to make them better able to accomplish their missions may seem very self-centered.

Yet in fact, one of their justifications is that business schools and management faculties have a high level of awareness of their social responsibility to train competent managers who, through their activities in companies and organizations in general, contribute to well-being and progress throughout society.

But beyond this important social contribution through their graduates, the COVID-19 crisis has helped to reveal how business schools themselves are real social actors. If the inclination already existed for business schools to act as a positive force for social progress, the COVID-19 crisis has greatly accelerated this trend (Cornuel and Hommel, Reference Cornuel and Hommel2012).

This is arguably the most remarkable aspect of the COVID-19 crisis in the management education sector. Beyond the fact that schools have deployed powerful mechanisms to maintain and improve their teaching activity and its quality, there are many cases in which business schools have stepped forward to provide answers to the social difficulties created by COVID-19.

For these schools, it goes well beyond educating students and executives – it is a question of engaging as a social actor contributing to society’s response to the COVID-19 crisis by employing the skills present in the schools themselves, the research that is developed there, the social influence and mobilization capacity of these institutions, and so forth. The forms this commitment takes are diverse: offering assistance to companies by providing them with volunteer consulting; providing leadership support to help businesses meet the challenges created by the coronavirus crisis; creating labs for ideas and being a creative force in a region or for a network of for-profit or nonprofit organizations, in certain cases accompanied by a workforce commitment in the field; and so forth.

Occasionally, schools have mobilized to seek answers to the problems created by the coronavirus crisis at a particular organization. Thus, Wharton accentuated an existing partnership with the Philadelphia Zoo (Symonds, Reference Symonds2020). The university took the initiative to help the zoo find responses to the lack of visitors during the coronavirus crisis period, an issue that posed problems for zoo maintenance, for the mental and physical well-being of the animals, and especially for the educational programs of Philadelphia schools.

In many cases, schools made a commitment to the business community by identifying territories, particular branches, or even companies that could benefit from expertise in dealing with the COVID-19 crisis (and by providing them with students, professors, graduates, and/or business professionals with whom the school is in contact, to help deal with a particular problem). Sometimes, schools brought together representatives from these various groups to form a task force, a think tank, or a convivium on behalf of a company or a particular business community.

It is particularly remarkable that in almost all cases, the approach followed by the business schools was initiated by a clear desire to help the community and society through an action developed with (or in favor of) companies.

In most cases, it was the business school that offered its services, knowing that its integration into the business world and into society had put it in a position to spot a problem. It should be noted that the cases in which companies went to schools to ask for their support (less numerous, but they do exist) are no less revealing of the position occupied by the schools in the business community and in society.

It is also interesting to note that the schools based their intervention on already-existing systems (portals, webinar creation, project guidance, start-up labs, executive education activities, applied research, workshops, etc.) that, prior to the COVID-19 crisis, had developed expertise that proved to be relevant in the time of the crisis.

The mobilization of schools’ assets to develop a response to the COVID-19 crisis was also achieved through the mobilization of graduates. In this respect, the China Europe International Business School (CEIBS) was a paroxysmal case in terms of both its scale and impact and the fact that being a Euro-Chinese school, with its historical base in Shanghai, China, an acute awareness of the importance of what was at stake was established very early on. However, CEIBS, through its action, has been a particularly successful example of schools mobilizing their graduates and also their students: by donating masks, raising funds, offering free services, providing medical equipment, and volunteering in the local communities, students and graduates have responded to the pandemic in Hubei with agility and compassion, as shown by the following examples (communicated via both personal communication with the dean and via news releases on the school’s website):

Within 24 hours, the CEIBS graduates’ association collected 12 million RMB when the donation project was announced on January 30, 2020.

By the end of May, CEIBS had collected a total of 1.285 billion RMB. The value of the donated materials reached RMB 474 million.

With the coordinated assistance of 26 CEIBS alumni sections, the procured medical supplies were distributed to nearly 100 provincial and municipal medical teams in Hubei in just a few days.

Alumni companies have also contributed (and continue to contribute) according to their capacity. For example, alumni companies have distinguished themselves by implementing the following examples:

∘ The Fosun Group set up a global command center, which quickly delivered donated materials to the front line through its sourcing network covering 23 countries.

∘ At JD Logistics, more than 100,000 employees across China made a concerted effort to ensure that emergency materials were reasonably coordinated, shipped in an orderly fashion, and delivered quickly.

∘ Yuwell Medical mobilized its employees to work overtime to ensure the supply of medical materials.

CEIBS alumni sections abroad also spontaneously organized to provide meals, masks, and travel assistance to those who were temporarily stranded.

The proactive approach of management schools, the desire to “do good” and contribute to resolving the problems posed by the COVID-19 crisis, is attested by the fact that the know-how (particularly in terms of hackathons and digital platforms) has led to particularly innovative approaches that are the reversal to those seeking to help a company, a business community, a region, or a particular employment area. That is, they seek to tackle a general problem (creating organizations that are resilient to the coronavirus crisis, strengthening health systems, developing social solidarity in the face of COVID-19, avoiding the exclusion of elderly people who must confine themselves, etc.). A platform makes it possible to solicit proposals worldwide while retaining or encouraging individual commitment from students, teachers, and the school. This involves facilitating the creation of start-ups (by providing a toolbox for such creation), giving support to actors already in activity who face a particular challenge, and so forth. In most cases, the project has a limited duration (on the order of 2 or 3 months), but the school supports certain projects over the long term (and it is assumed that for others, a decisive impetus was thus given). In addition, the objective of crisis-management training for students (and also for all participants) is also included in such projects.

All of this allows for both the type of social integration that business schools have been enacting in their new role as full social actors and the way in which the entire sphere of management education has faced the COVID-19 crisis.

Conclusion

The analysis of the consequences of the COVID-19 crisis on management education institutions reveals to what extent this crisis profoundly modifies our understanding of this sector.

Two types of particularly noteworthy lessons can be drawn, corresponding to the two levels at which the response of the management education institutions sector has been structured.

At the first level, a notable effort was made to allow the continuing education of management students and the populations of executives and managers. This happened in various ways, including switching entirely to distance education, attempting to maintain face-to-face teaching when possible and often preferentially, and moving to hybrid teaching styles. In addition, the response of the schools, which endeavored to maintain the most “normal” operations possible, focused as much on teaching questions and questions of selection for the following year as on research questions.

Yet it is remarkable that some schools have gone beyond the quest to operate as efficiently as possible. They have mobilized as full-fledged social actors to help respond to the difficulties caused by the coronavirus crisis at the societal level. This desire to intervene hic et nunc, as outlined previously, deserves to be highlighted. It resonates with a problem that emerged for business schools during another crisis – that of 2008. At the end of it, the observation that business schools had done a remarkable job in teaching the techniques, skills, and tools of business administration but had failed in their mission to instill ethics in their students sparked debates that have spread throughout the world of management education.

It appeared that Milton Friedman’s position that “there is one and only one social responsibility of business – to use its resources and engage in activities designed to increase its profits” (Friedman, Reference Fox1962/2002, as quoted by Fox, Reference Fox2012, para. 2) best illustrated the approach that business schools were at that time teaching. They seemed to ignore the fact that the Friedman quote is truncated; Friedman went on to write: “so long as it stays within the rules of the game, which is to say, engages in open and free competition without deception or fraud” (Friedman, Reference Fox1962/2002, as quoted by Fox, Reference Fox2012, para. 2). In fact, the foundation of the education provided lay in a misunderstanding of Friedman that had led management education institutions to limit corporate social responsibility to the creation of profit (which was supposed to contribute to the future well-being of the company) by neglecting the present social impact of the company. The “hic et nunc” became properly unthinkable in the social domain.

To remedy this state of affairs, following the 2008 crisis, many institutions, among which the European Foundation for Management Development (EFMD) ranked first, as well as many thinkers and researchers in management and just as many business leaders, stressed the need to reintroduce ethics and social responsibility to business schools. But on the question of how, the responses and proposals hardly went beyond the suggestion of strengthening and enriching the ethics and social responsibility courses. The fragility and the lack of impact of this suggestion made the sphere of management education expect a more appropriate and powerful response to this major challenge.

The response to the COVID-19 crisis shows how far schools have come and how much progress they have made. Management education institutions are no longer satisfied with responding to the crisis by maintaining and deepening their standard operations. They position themselves as actors intervening directly to help solve social problems. They see their roles as including social responsibility and the need to act in response to it here and now.

Thus, the COVID-19 crisis shows that the management education sector has made progress and has moved into a new stage in its maturity.

At the second level, the COVID-19 crisis has changed the balance between regional and global development within management education. Obviously, in recent decades, the world of management education has placed great emphasis on the importance of internationalization. The EFMD itself has preached a great deal in favor of the internationalization of faculty, research topics, student recruitment, and so forth. The importance of following this development was evidently apparent, insofar as it enriched debate in the classroom while avoiding the obvious topics and commonplaces that are the subject of consensus only in a very reduced geographical and social framework. In such a context, the development forced research to gain ground and to take a breath of fresh air and made it possible to increase sensitivities and approaches among professors and others. For example, the need for a high level of internationalization has often arisen in order to obtain accreditation for a school or for a program.

The COVID-19 crisis seems to have marked the return of the territorial, the regional, and the national in the field of management education. This is not surprising because the same trend has emerged in many areas, including health, defense, and food: the need for territorial anchoring – to avoid being in a situation of strategic dependence and the impossibility of defining a policy – has reappeared in the light of the many tensions that our societies face because they no longer control their own production and supply chains. It is therefore not surprising that jointly in the field of education management, the importance of not sacrificing territorial, regional, and national anchoring for the benefit of international anchoring is reimposing itself. For example, the prospect that the flow of foreign students (which had seemed to want to increase steadily on campuses) would slow down, that their proportion in the student body would decrease, reappeared after having been forgotten for 30 years. There has been a sudden reemergence of the importance of the fact that management education institutions are often important local, regional, and national institutions – places that have shaped local leadership for years, institutions whose names enjoy an important local aura that partly guarantees the development of the institutions. In addition, the examination of the commitments of schools in favor of the resolution of social problems created by COVID-19, mentioned previously, shows that in most cases, this commitment took place at the level of the primary anchoring territory of the schools – that is, regional or national rather than international. All of this encourages a rebalancing of the approaches brought into play by the management education sector. This rebalancing is certainly the bearer of new developments for management education that are better anchored in the humanities because it avoids culturally disembodied and socially evanescent approaches.

Introduction

The current COVID-19 crisis has triggered unprecedented upheaval on a global scale. From a strictly public health point of view, however, humanity has proven itself capable of joining forces and transcending political boundaries.

The Crisis Is Transforming Management and Leadership

Coming hot on the heels of our bicentenary year, the pandemic has had a severe impact on the work of École Supérieure de Commerce de Paris (ESCP) across all of our European campuses, affecting our faculty members and international students alike. The crisis has confounded forecasters completely and now raises serious questions as to the responsibilities of managers and the meaning attached to their work.

For the heads of higher education institutions, this issue takes on a dual significance. First and foremost, there is the question of the meaning, usefulness, value, and purpose of the knowledge we produce for society in general. Then, of course, there is the dissemination of actionable knowledge for the benefit of our stakeholders: students, alumni, businesses, organizations, and public administrations.

As deans of business schools, our duty reaches above and beyond the production and dissemination of knowledge, methods, and managerial practices. It also consists of guiding and responding to events and overseeing the constant adaptation of individuals within structured social systems.

Finally, as an academic specializing in leadership, I find myself wondering how business schools can best prepare the business leaders of the future for the challenges they will be facing.

I. Rethinking Leadership after the Experience of Multiple Lockdowns

1. ESCP as a Pan-European Business School

Our school was founded in 1819 and has rarely closed, even during the darkest periods of the three wars of 1870, 1914, and 1939. ESCP has 7,300 students in initial training, in programs ranging from bachelor to doctorate, and 5,000 managers in executive education (ExecEd). The school is unique in that it boasts campuses in six European countries, with national recognition as a Grande Ecole in France, as a university in Germany by the Berlin Senate, as a university in Italy, as a university in Spain, and as a British higher education institution. All of these campuses are managed and coordinated by a team that is united around European values and the ESCP culture: Excellence, Singularity, Creativity & Pluralism.

The pandemic has hit ESCP in several waves:

The first phase came in February–March 2020, when our Turin campus was the first to be hit. The resilience and relevance demonstrated by the Italian entity in its reactions provided some good practices for the benefit of the school as a whole, as the Madrid, Warsaw, Berlin, and Paris campuses were then confronted in turn with the challenges of managing a school in lockdown. Finally, the London campus was the last to close. During this initial lockdown phase, the school capitalized on its previous experience of coordinating multiple campuses, and our faculty members built on their experience of using digital tools. There was a reconceptualization of the student recruitment process for the start of the 2020–21 academic year, with written tests but no oral interviews so as to place all candidates on an equal footing, whatever inequalities there might be in their access to good-quality digital facilities. We must salute the continued research efforts by the faculty who leaped into action and succeeded in producing Managing a Post-Covid19 Era (Bunkanwanicha et al., Reference Bunkanwanicha, Coeurderoy and Ben Slimaneecsp2020), a collection of impact papers enabling students, employers and companies, and governments to better understand the global pandemic and its multifaceted implications for our societies.

The second phase came with the start of the new school year, from September 2020 through to the end of the year. After a start to the new school year with the students present in person, in compliance with the health regulations, a second partial lockdown was put in place with the introduction of a curfew. Because the various governments did not all make this decision at the same time, the organization of student mobility was disrupted, but it did provide an opportunity to put the new teaching facilities to use. At ESCP, we opened the Phygital (contraction of physical and digital) Factory, a place where our faculty can record their teaching modules easily. At the same time, increasing proportions of remote courses were organized, both synchronously and asynchronously. As an indication, whereas 3,070 courses were delivered online during the first lockdown, the second lockdown saw a significant increase to 4,200 online courses, representing more than 80,000 hours of teaching. ESCP has now entered a period of “Mobility and Motility” where students keep enjoying the experience of physical mobility and the experience of learning in just moving intellectually.

The third phase began in January 2021, with the various states making different decisions regarding the physical presence of students in higher education institutions. The latter is currently in a hybrid phase, with the possibility for students to return, subject to a maximum of 20 percent of the students physically present. However, the schools have now mastered the digital tools for the courses and services they offer, which is a big difference compared to the first lockdown. In March 2020, the schools were unable to organize the recruitment orals. This year, however, they will take place digitally, which shows the confidence higher education institutions now feel in their adaptation to digital technology. However, there is a feeling of weariness at present – weariness with the digital world, as well as with the lack of social contacts for our young people at a very important time in their student lives. It is this psychological aspect that led President Macron to keep the schools open. This third phase has also brought an awareness that ExecEd will no longer concern the same services or same profiles, and we will come back to that in detail in Part II. Similarly, in the governance of higher education institutions, meetings are taking place with a high level of quality, especially board meetings, and the same goes for the governance of the EFMD board and the EFMD deans conference, which I was able to attend at the beginning of February 2021. The level of satisfaction of the deans was very high, despite the distance and lack of real contact.

2. Responding to the Pandemic: Our Eight Key Takeaways

In short, the school’s internal stakeholders – students, faculty, administrative staff – have been strongly mobilized, and from our vantage point today, at the beginning of 2021, we can outline eight practical lessons that will inevitably change the way a Business School is run, in a lasting manner.

1. Taking the 20-40 digital turn today: ESCP has become convinced that neither students nor management research has anything to gain from the uberization of the business school model. What is needed is more widespread use of the forms of blended learning that were already emerging before the pandemic. We have also chosen to give the teaching staff a great deal of pedagogical flexibility. Looking to 2040, it has been decided to have a minimum of 20 percent digital and 40 percent in-class teaching for all courses. This will allow some teachers to favor 80 percent of class time with their students present in person and 20 percent remote, for example, or others might prefer to divide their teaching into 40 percent face-to-face content and 60 percent digital. This will make it possible to adapt the pedagogy of management disciplines. The challenge now is to produce digital modules that can be integrated into a symbiotic face-to-face architecture.

2. Delivering premium asynchronous courses: The crisis has revealed the need to provide students with courses of the highest standard wherever they are in the world. This has led many business schools to produce prerecorded (asynchronous) modules to take account of the realities of time-zone differences. Pedagogically, the production of an asynchronous module is much more demanding than filming a synchronous course livened up by questions from students. The asynchronous module must captivate the learner from beginning to end by means of a teaching sequence that is punctuated with videos of illustrations and quizzes for midterm evaluations, along with impeccable presentation materials.

3. Rethinking ExecEd: As will be discussed in Part II of this chapter, the changes underway in ExecEd are drastic. Corporate expectations will be radically different once the pandemic issues are resolved. The share of digital methods will increase, whereas the duration of seminars will be shortened considerably. Business school professors will be invited as expert witnesses, rather than as the half-day facilitators they were in the past, when they would give presentations with (albeit sophisticated) overhead transparencies and pass from one subgroup room to another to encourage executives to solve case studies. If the business school professor previously took the lead over the group of learners, it will now be the university or a pedagogical coordinator it has appointed who will lead the group of business school professors invited to the company’s training.

4. Striking a new equilibrium between research and teaching: The rise of digital technology will require business school deans to speed up the production of educational capsules for students and continuing education managers in a short space of time. This will have consequences for business school rankings, where the quality of an institution will be measured in terms of research, student selectivity, the pedagogical quality of teachers, and the size of the business school’s digital offering. Digital technology will not replace research; it will become an additional criterion for evaluation.

5. Launching a massive real estate plan despite the uncertainties: The question of business school real estate is being raised once again as we move from managing real estate to digital estate. The need will shift from managing classrooms, floor space, and teacher researchers’ offices to questions of ergonomics, furniture, and equipment adapted to digital technologies and teaching resource storage capacity in terabytes.

6. Not resting on the success of our flagship programs: Digitization is reshuffling the cards when it comes to educational portfolios, with the expected flowering of specialized and regularly updated digital certificates. The accumulation and combination of these certificates can lead to lifelong diplomas.

7. Anticipating what Google, Apple, Facebook, Amazon, and Microsoft (GAFAM) and educational technology (EdTech) will be able to offer tomorrow: This will involve establishing a position for the major digital and EdTech companies in higher education. They have a technological advantage in the global spectrum and have the financial muscle to acquire renowned universities, but they also run the risk of being rejected by the governments that serve as regulators of higher education. In any case, business schools will not be able to avoid taking this potential new player, partner, and predator into account.

8. Positioning higher education institutions in relation to EdTech: It is striking that there is much more talk about the transformation and innovation of EdTech companies than about the transformation of business schools. EdTech companies tended to be seen as subcontractors for the business schools before the pandemic, and increasing digitalization should not reverse that relationship. It would be a bit like science being hosted by Wikipedia.

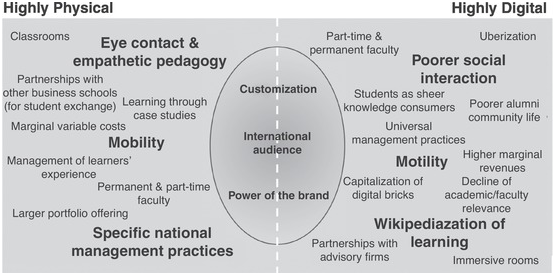

Business schools must therefore skillfully weigh up the advantages and risks when they engage in a pedagogical mix that combines physical and digital. Figure 14.1 shows the main elements to be taken into account, bearing in mind that there is no absolute “one best way” and that a balanced mix needs to be constructed according to parameters such as the duration of the training, the level of the participants, the size of the group, and the variety of the international audience.

Figure 14.1 Finding the right pedagogical mix.

3. Executive Profiles and Competencies

In a recently published work, Rebecca Henderson (Reference Henderson2020) of Harvard Business School explains that managers now have no choice but to totally reinvent capitalism. In La Prouesse Française (French Prowess), published in 2017, I insisted on the defining characteristics of the French style of management, highlighting its strengths and the weaknesses in need of a rethink (Suleiman et al., Reference Suleiman, Bournois and Jaïdi2017).

The COVID-19 crisis has thrust this debate front and center. Attentiveness to well-being at work, respect for individuality within groups, and a commitment to the greater good are all key pillars of European humanist culture. These values have come rapidly to the fore through the decisive measures taken to protect citizens, respect individual liberties, and prepare for the economic recovery of the European Union.

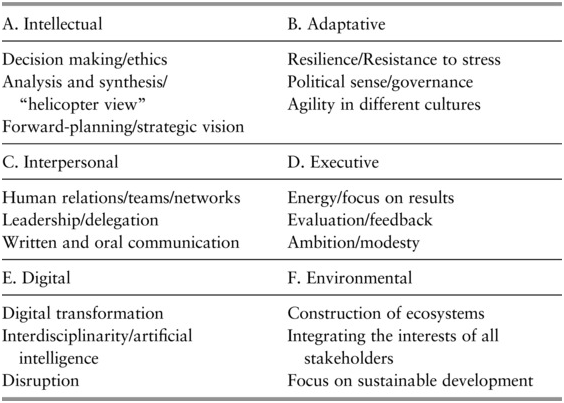

Leaders in both the public and private sectors are acutely aware of the impact of this enforced pause, this moment of reflection on a global scale, and must learn the lessons of the current crisis. Going forward, the six major dimensions identified in Table 14.1 will be of primary importance by 2030.

Table 14.1. Qualities and Aptitudes Required of Future Leaders

| A. Intellectual | B. Adaptative |

|---|---|

Decision making/ethics Analysis and synthesis/“helicopter view” Forward-planning/strategic vision | Resilience/Resistance to stress Political sense/governance Agility in different cultures |

| C. Interpersonal | D. Executive |

|---|---|

Human relations/teams/networks Leadership/delegation Written and oral communication | Energy/focus on results Evaluation/feedback Ambition/modesty |

| E. Digital | F. Environmental |

|---|---|

Digital transformation Interdisciplinarity/artificial intelligence Disruption | Construction of ecosystems Integrating the interests of all stakeholders Focus on sustainable development |

The ESCP Community Rises to the Occasion Once Again

I could not be more impressed by, or proud of, the monumental work done by the ESCP faculty – and all in record time! Students, alumni, and decision makers will find herein a rich profusion of ideas, debates, and pragmatic proposals for the future of the post-2020 economy.

What variety and depth of talent we have in the academic community of our business school! All of our European campuses, all of the disciplines of management studies, and all of the principal dimensions of decision making are represented here. Six overarching themes emerge, corresponding to the major challenges awaiting managers: the digital transformation (particularly at work); the limits of individualism and the rise of new forms of collective action; inclusive management/leadership; the resilience of businesses in times of crisis; uncertainty and the need for change (or stability) in the financial markets and the markets for goods and services; and finally, the challenges this crisis raises for higher education.

II. Business Schools Must Engage in Strategic Partnerships

During the past decade, large companies have made profound changes to the way they design programs within their corporate universities. Overall, they have shortened the duration of seminars for senior executives and managers, professionalized their program managers, internationalized the sourcing of their speakers, increased the variety of teaching tools, opened up the themes to include individual development and codevelopment, introduced metrics to systematically evaluate the added value perceived by participants, and so on.

This has led to the creation of much more varied ecosystems than in the past. The main idea behind this contribution is to show that the Grandes Écoles no longer have to do everything in-house, from collecting the company’s needs to providing certificates once the seminar is over, including the implementation of face-to-face or distance learning sequences. The trend that is emerging for the new decade will consist of business schools creating, devising, and professionalizing partnerships with other business schools, with consortia of leading companies in certain sectors of activity, and most certainly, with the leading professional service firms (PSFs), the consultancy firms for which education is at the heart of their strategy.

The ExecEd environment will be different tomorrow, driven by new quality expectations, a new relationship to the workspace, and new organizational and time-management habits. New types of partnerships will flourish in the coming decade. They will deliver diplomas and certificates from largely digital offerings, and the highest-profile and most reputable of them will succeed in attracting corporate leaders to take on a doctoral thesis based largely on their professional expertise.

1. Digitalization and Customization as Partners

Among the major developments of the past decade, there is one absolute certainty: digitalization is going hand in hand with the customization of ExecEd needs. The interviews I have conducted with many directors of corporate universities underline the trend toward microlearning, that is, highly specialized, carefully customized modules. At first glance, this may seem paradoxical if we think that digitalization boils down to automation, the accumulation of teaching resources, and increasing storage of knowledge (knowledge accumulation). In fact, if we know how to identify the needs of each learner in detail (senior executives and managers), if we know their previous experience, their personal approach to the digital world, and the time they have available for their personal training, then digitalization will make it possible to (1) provide them with specific resources, (2) guide them in their choice of modules, (3) provide them with numerous self-assessments, and (4) provide them with points of reference in relation to other managers in their category, all while respecting their rate of progress in conjunction with their direct bosses and line management. To do this, three main conditions must be met:

1. The business school must have a vast pool of teaching resources at its disposal.

2. The business school must have an information system linked to its teaching; this does not exist in many cases because the information systems mainly manage the administrative life of the business school, leaving pedagogical matters in the hands of teachers. If the business school succeeds in establishing the connection between pedagogy and information system, this opens up numerous possibilities for tracing individual paths and maintaining the motivation of participants to go further.

3. Because of the faster obsolescence of management knowledge, it is essential to have knowledge that is constantly updated and targeted by sector of activity, company size, and management issue. This is all the more essential because ExecEd is increasingly committed to lifelong learning, with shorter programs that are more dispersed throughout the career.

Today’s business school, taken in isolation, with its permanent faculty of between 150 and 300 professors generally, will not be able to provide the answers to this variety of needs requiring constant updating and dealing with heterogeneous business sectors and countries.

Alliances will be required, first to boost the revenues that will be increasingly necessary to finance investments (growing faculty size, digital development, rethinking buildings and real estate, etc.). Business schools will not disappear totally – there will always be a need for research production and teaching professionals (management faculty reproduction). The decade from 2010 to 2020 saw the Shanghai research ranking reach its acme, introducing a race toward high productivity in research, and business schools will continue to be ranked according to their ability to select the best students, their ability to produce research, and their ability to produce and market attractive and updated digital modules.

2. Partnerships at a Crossroads

In terms of alliances to be made, business schools are currently at a crossroads; according to the trendsetters, these alliances will be of four main kinds:

1. Alliances inside the existing network of business schools in order to provide a broad range of resources, combining materials from reputable business schools located in different geographies: the CEMS, with Bocconi, Cornell, Calcutta, and Keio, among others, is one illustration of a such a pioneering initiative.

2. Alliances with a consortium of companies (by sector, size, country). Business schools, mostly those with specialized know-how (supply chain, finance, leadership development, etc.), will thrive on a real-time connection with industrial partners. The latter will provide the expertise and high-caliber teaching leaders that will make the consortium extremely attractive to students.

3. Alliances with EdTech are also very likely, although there are risks of cannibalization. EdTech companies will be seeking academic legitimization, whereas schools will be in search of technological innovations.

4. Alliances with consulting companies will certainly be more promising because business schools and professional service firms (PSFs; consulting and advisory firms) are almost next of kin. Both are knowledge extensive and have education as a common differentiating factor. Business schools have the mission of grooming future leaders, whereas PSF or audit and advisory firms excel in tailoring management advice to the upper echelons of organizations.

My take is that it will be hard for business schools to establish sustainable alliances with all of these different players at the same time. Business school deans and governance will find themselves facing strategic choices and having to weigh up the relative benefits of their newly wrought relationships: the likelihood of boosting ExecEd revenues, raising their profile and enhancing their reputation, creating a sustainable and inimitable advantage, and increasing outstanding faculty and selected students.

3. Partnerships for MBA and Doctorate Programs

Alliances may also develop on several specific program levels (bachelor, master/MSc, and PhD). I would take the example of the visionary Next MBA program that Mazars developed in 2012 with participants from six or seven leading international companies. In this spirit, Mazars is working with business schools to develop its top leaders through a PhD degree. It provides the experience of research, with the dissertation topic being aligned with the job profile of the future leaders. Whereas in the past, top leaders would not find the time to enroll in a time-consuming PhD program, in the 2020s, we will certainly see growth in executive PhDs for senior managers eager to look at their practice with hindsight and contribute to management science. Such doctoral undertakings are very likely to have the following features:

1. Academic production focused on the hot managerial issues the leaders have on their front burners. In the near future, corporate social responsibility may very well also include academic social responsibility (ASR), especially in business environments fraught with risks of fast knowledge obsolescence.

2. These PhD degrees will serve as markers to differentiate the development paths of high-caliber leaders who will be seen as able to translate knowledge into action. As PhD holders, they will obtain a token of in-depth investigation skills and a sign of helicopter-view abilities.

3. Their doctoral pieces may get published in journals because they will present guarantees of scientific regard, as well as transferability to practitioners.

4. These future “leaders and doctors” will ideally be mentored by a tandem of two PhD supervisors representing the two worlds of academia and practice, very much in the approach and spirit of Peter Drucker in The Practice of Management (Drucker, 1955/Reference Drucker2007):

Above all, the new technology will not render managers superfluous or replace them by mere technicians. On the contrary, it will demand many more managers. It will greatly extend the management area, many people now considered rank-and-file will have to become capable of doing management work. The great majority of technicians will have to be able to understand what management is and to see and think managerially. And on all levels the demands on the manager’s responsibility and competence, his vision, his capacity to choose between alternate risks, his economic knowledge and skill, his ability to manage managers and to manage worker and work, his competence in making decisions, will be greatly increased.

5. PhD dissertations of this new kind will necessarily be innovation oriented. Disruptive methodological approaches must be encouraged.

6. It goes without saying that digital transformation aspects will be central to most dissertations of the 2020s.

7. The augmented “doctor and leader” is bound to play a key role in the dissemination of knowledge to peers internally and clients externally. This constitutes a radical change from the times when knowledge was reserved only for the learned.

4. The Making of the New Corporate University

From all of the previously discussed points, the profile of tomorrow’s new corporate university will emerge. Broadly speaking, its characteristics will include the following:

1. A close link with the company’s strategy. The role of the university will clearly be seen as a support mechanism for the company’s global strategy. A specific budget will clarify the contributions of each participant (business units, central budget, the participants themselves, etc.), whether for training activities or for obtaining certificates and diplomas, because all this will be done in the framework of partnerships with business schools.

2. Close coordination with career management. More than ever, the corporate university will be linked in with the systems for identifying potential and career development. Several modalities will exist on the spectrum:

Option 1 – participants are sent by career management.

Option 2 – the university defines the profiles of the participants it hosts.

3. Identification of target populations. This presupposes the existence of a sufficient internal population to justify the existence of a dedicated structure. In terms of volume, we find the following:

Level 0 – COMEX and extended COMEX (top 300)

Level 1 – COMEX-1 staff and leading experts (top 2,000). Integrate expertise and functional aspects.

Level 2 – those considered capable of joining level 1 (“key players”).

Level 3 – “key business lines of the company.” The aim is to provide business units with training that is specific to their profession and know-how.

Level 4 – “customers, suppliers, and ecosystem.” Corporate universities will also develop modules bringing together the different stakeholders in the company. In the extreme, participants from competing companies will reflect together on sector developments. The environmental, social, and governance (ESG) dimension will be more prominent than ever before in the modules and certificates issued.

4. A range of offers. There will be variety in the portfolio of education courses, their durations, e-learning methods, certification, and the possibility of combining several modules that will progressively earn credits towards obtaining a diploma. All the content will be updated very regularly. Participants will also be the developers of modules for others.