A New Literary History of the Long Twelfth Century

A New Literary History of the Long Twelfth Century Book contents

- A New Literary History of the Long Twelfth Century

- Cambridge Studies in Medieval Literature

- A New Literary History of the Long Twelfth Century

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Figures

- Acknowledgements

- Conventions Used

- Abbreviations

- Part I Preliminaries

- Part II The Affordances of English

- Bibliography

- Index

- Cambridge Studies in Medieval Literature

- References

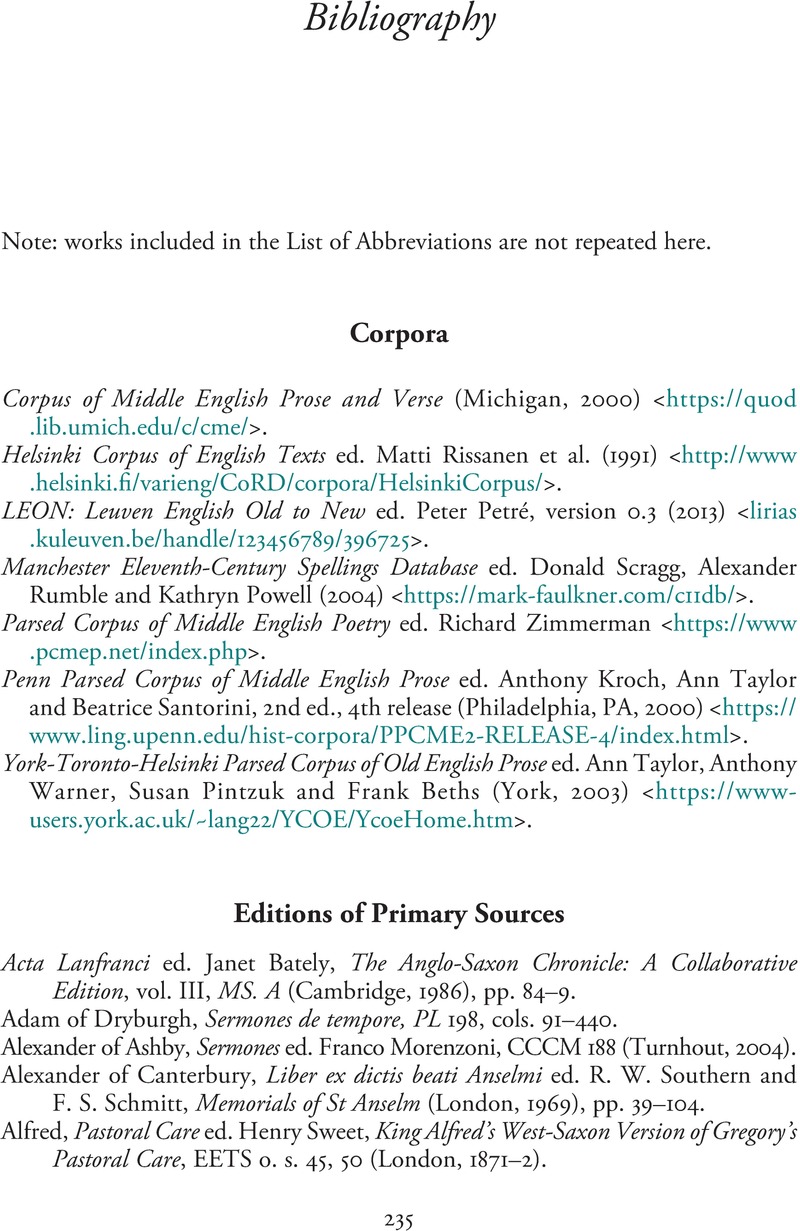

Bibliography

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 14 July 2022

- A New Literary History of the Long Twelfth Century

- Cambridge Studies in Medieval Literature

- A New Literary History of the Long Twelfth Century

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Figures

- Acknowledgements

- Conventions Used

- Abbreviations

- Part I Preliminaries

- Part II The Affordances of English

- Bibliography

- Index

- Cambridge Studies in Medieval Literature

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- A New Literary History of the Long Twelfth CenturyLanguage and Literature between Old and Middle English, pp. 235 - 277Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2022