Book contents

- Civil War and the Collapse of the Social Bond

- Classics after Antiquity

- Civil War and the Collapse of the Social Bond

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Dedication

- Contents

- Figures

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 Figures of Discord

- Chapter 2 Oriental Empire

- Chapter 3 Empire without End

- Chapter 4 The Eternal City

- Chapter 5 The Republic to Come

- Chapter 6 The Empire to Come

- Bibliography

- Index

- References

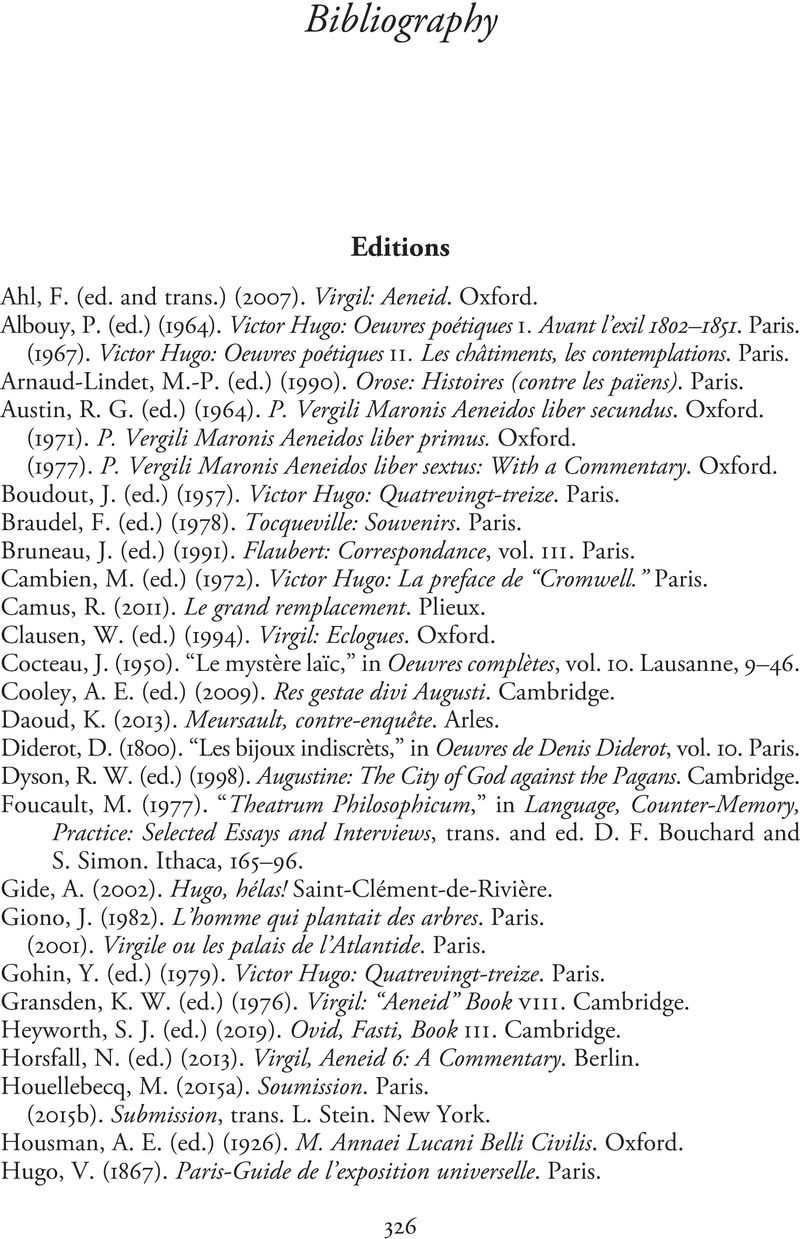

Bibliography

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 06 October 2022

- Civil War and the Collapse of the Social Bond

- Classics after Antiquity

- Civil War and the Collapse of the Social Bond

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Dedication

- Contents

- Figures

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 Figures of Discord

- Chapter 2 Oriental Empire

- Chapter 3 Empire without End

- Chapter 4 The Eternal City

- Chapter 5 The Republic to Come

- Chapter 6 The Empire to Come

- Bibliography

- Index

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Civil War and the Collapse of the Social BondThe Roman Tradition at the Heart of the Modern, pp. 326 - 355Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2022