Book contents

- Reproductive Realities in Modern China

- Cambridge Studies in the History of the People’s Republic of China

- Reproductive Realities in Modern China

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Figures

- Tables

- Acknowledgments

- Note on the Text

- Introduction

- 1 Building a Fitter Nation: Eugenics, Birth Control, and Abortion in Public Discourse, 1911–1949

- 2 Birth Control in Practice

- 3 Reaping the Fruits of Women’s Labor: Birth Control in the Early PRC, 1949–1958

- 4 “Birth Planning Has Many Benefits”: Weaving Family Planning into the Fabric of Everyday Life, 1959–1965

- 5 Controlling Sex and Reproduction across the Urban–Rural Divide, 1966–1979

- 6 The Rise and Demise of the One Child Policy, 1979–2015

- Epilogue: Birth Control and Abortion in the Longue Durée, 1911–2021

- Appendix: Interviews

- Glossary

- References

- Index

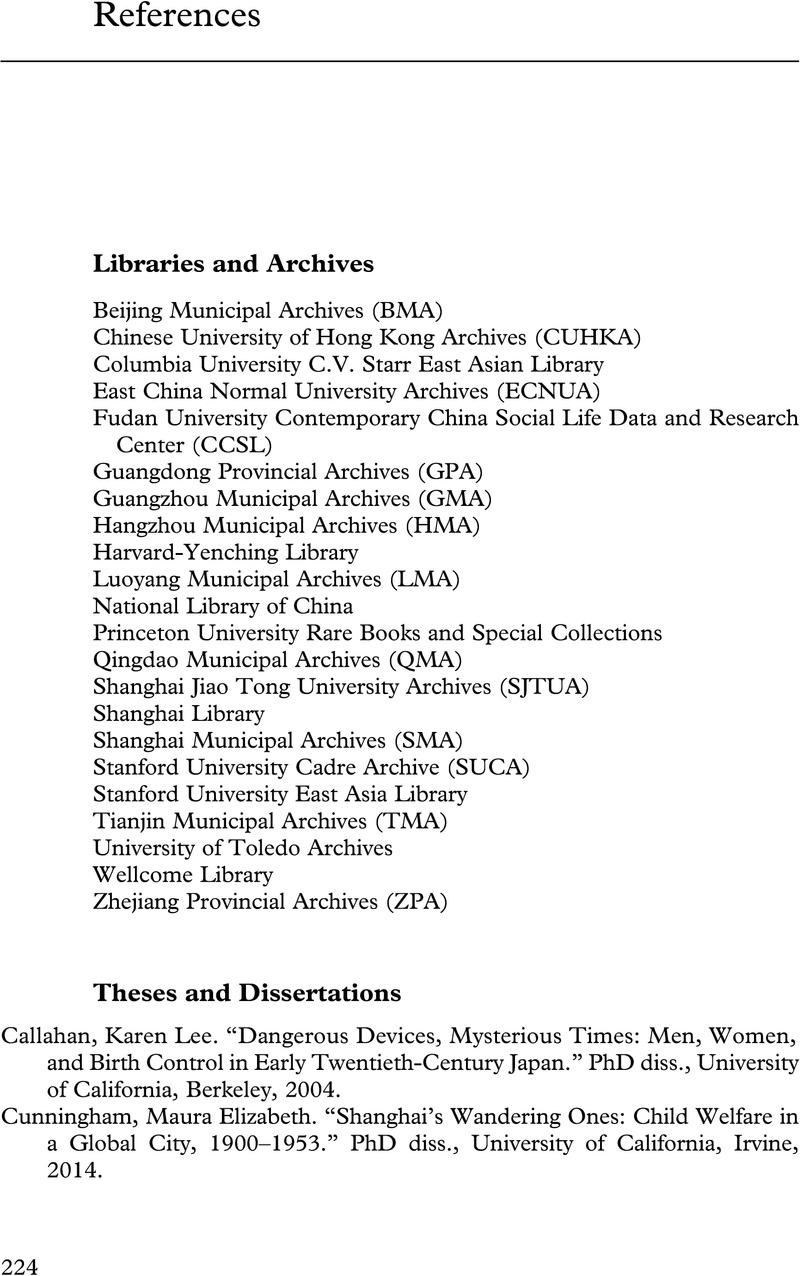

- References

References

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 19 January 2023

- Reproductive Realities in Modern China

- Cambridge Studies in the History of the People’s Republic of China

- Reproductive Realities in Modern China

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Figures

- Tables

- Acknowledgments

- Note on the Text

- Introduction

- 1 Building a Fitter Nation: Eugenics, Birth Control, and Abortion in Public Discourse, 1911–1949

- 2 Birth Control in Practice

- 3 Reaping the Fruits of Women’s Labor: Birth Control in the Early PRC, 1949–1958

- 4 “Birth Planning Has Many Benefits”: Weaving Family Planning into the Fabric of Everyday Life, 1959–1965

- 5 Controlling Sex and Reproduction across the Urban–Rural Divide, 1966–1979

- 6 The Rise and Demise of the One Child Policy, 1979–2015

- Epilogue: Birth Control and Abortion in the Longue Durée, 1911–2021

- Appendix: Interviews

- Glossary

- References

- Index

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Reproductive Realities in Modern ChinaBirth Control and Abortion, 1911–2021, pp. 224 - 244Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2023