Introduction: Joe Sacco’s Seismic Lines

Seismic lines carve out the frontiers of resource extraction in Canada’s Northwest Territories today. They are exploratory technologies used by multinational conglomerates to identify subterranean oil and gas reserves. First, vertical and horizontal corridors are cut through the region’s dense boreal ecosystems, clawing the surface of the earth into a physical grid. After these vast segments of forestry have been cleared to allow access for heavy machinery and equipment, a series of “shot holes” are plunged into the ground all the way along the lines and packed with small explosives. When detonated, these explosives generate seismic waves that ricochet unevenly against the subsurface rock formations. Their returning sonars reveal subterranean reservoirs of oil and natural gas, locating opportunities for future extraction. Seismic lines thus subject the landscape to a visuality that operates not in two, nor three, but four dimensions: they sound out the ground beneath the surface of the territory to locate historic repositories of fossil futures.Footnote 1

The renowned comics artist and journalist Joe Sacco first traveled to Canada’s Northwest Territories to learn more about the fracking industry in the early 2010s, but he soon found himself drawn to the historic and contemporary struggles of the Dene, an indigenous people who “have lived [in the region] since ‘time immemorial.’”Footnote 2 It is the Dene’s testimonies, experiences, and histories that fill the pages of his most recent book, Paying the Land (2020), the title of which is taken from the Dene custom to “pay the land” or “bring the land a gift”: to “treat it gently, not dig holes or make too much of a disturbance” (50). What follows is a detailed account of the ways in which the Dene way of life has been steadily enclosed by capitalist modernity through the force of a very particular kind of line.

Postcolonial and decolonial scholars have long shown how colonial lines are epitomized in the modern cartographic map, where the line is used as a technology of delimitation and enclosure, often in relation to land.Footnote 3 These lines are drawn across territories, fragmenting communities and displacing populations, and prioritizing a property regime of occupation and ownership over terrestrial habitation and situated presence. They authorize borders, constructing with pens and treaties and seismic lines a colonial “visuality,” to use the nineteenth-century term revived and reapplied by visual theorist Nicholas Mirzoeff. Beginning in the slave plantation and evolving through the heights of European imperialism, visuality has functioned by combining the lines of maps with other forms of “information, imagination, and insight,” both to realize and to naturalize capital’s accumulative logics.Footnote 4 The word emerges with industrial modernity, appearing in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries to organize global space into a particular vision of “History”: for example, through the creation of racial categories, the containment of racialized people within territories, and their subsequent organization as variously “primitive” or “civilized” along a linear axis, visuality represents the combined and uneven processes of capital accumulation as teleologically linear and “progressive.”Footnote 5

In Paying the Land, Sacco breaks open visuality’s lines by etching the spatial consequences of modernity’s resource-fueled metabolism into the layout of his comic’s page. As comics critics have long shown, the graphic novel’s narrative form is predicated on the “discursive presentation of time as space on the page,” rendering it potentially adept at registering the spatiotemporal contortions and enclosures of capitalist modernity’s combined and uneven world.Footnote 6 With his panel arrangements and hand-drawn lines, Sacco assembles indigenous testimonies into the narrative time of his graphic novel, repeating and extending visuality’s representational regime: just as seismic lines draw the territory’s large boreal forests and subterranean resources into the systemic force field of capitalist modernity, so do Sacco’s own lines draw the Dene’s stories into the analogous system of the comics page, with the effect of implying the graphic novel as itself a form of “resource” extraction. As Thierry Groensteen has influentially described, graphic novels operate as narrative systems: they tell their stories through “an art of fragments, of scattering, of distribution” (uneven) and also “an art of conjunction, of repetition, of linking together” (combined) at the same time. Footnote 7 This grounding dialectic of the comic’s narrative system allows Sacco to register, with his hand-drawn lines, the combined and uneven development that has been displacing the Dene for centuries, and which currently continues to pulverize the Northwest Territories’ peripheral and semi-peripheral zones.Footnote 8

However, Paying the Land is more than an extension of the processes of commodification that have long been enclosing the Dene’s territories and lives. Through hand-drawn meditations on the visuality of settler colonialism in the Northwest Territories, Sacco effects a “peripheral realism” that draws the systemic continuities—as both physical dynamics and metaphysical logics—between different phases of colonial modernity into view.Footnote 9 These lines, which are loaded with the volume of frontier capitalism’s historic violence, are what I will describe as Sacco’s “seismic lines,” wherein I use the word seismic to emphasize the systemic connections among cartographic, bureaucratic, and infrastructural lines that Sacco’s drawings reveal. For the extractive logic underpinning the seismic line begins not with today’s fracking industry, but with the arrival of the first settlers in the region, and it extends from the drawing up of colonial borders and treaty claims to the land, through to the fracking infrastructures that identify and extract resources from the earth, and finally to Sacco’s own self-reflexive concerns about his extraction of indigenous testimonies for their inevitable commodification in his journalistic art. Of particular note is Sacco’s continuation of his long-standing artistic interest in the literal and metaphoric implications of volume (he likes his comics to be “loud”) and his use of “sound as a presence or marker of materiality,” to borrow from Rose Brister’s description of Palestine (2001).Footnote 10 By capturing the epiphenomenal as well as physical volume of settler colonialism in his seismic lines, Sacco renders concrete—and therefore legible—the systemic force of global capital’s “gravitational field.”Footnote 11

The first section of this article sifts through the multiple physical and conceptual conjugations that are folded into the systemic volume of Sacco’s seismic lines. Then, in the article’s second section, I work my way from peripheral realism towards what I call Paying the Land’s “terrestrial realism”: more than a peripheral realism because it involves the participation of the reader as well, terrestrial realism takes place not in the colonial but the decolonial lines from which the Dene’s way of life is composed. As the anthropologist Tim Ingold has shown, colonial modernity does not have a monopoly on lines. The lines of the sketch map, for example, leave a gestural trace that stakes out a “re-enactment of journeys actually made,” marking not an overarching occupation or enclosure of, but a terrestrial habitation in the world, that way claiming space where encounters and new solidarities might occur.Footnote 12 Rather than sketching the Dene in the valence of symptomatic readings or subaltern studies, with their emphasis on silences, absences, and gaps, the volume and gesture of Sacco’s lines asserts a terrestrial presence instead, one in which the reader is implicated and in which they are themselves invited to stand.

I finish by showing how Sacco’s hand-drawn lines thus produce a terrestrial realism that occupies a grounded space from which “the right to look”—the right, that is, to visualize visuality and grasp the totality it is designed to conceal—can be claimed.Footnote 13 By drawing out this space, my aim is not to claim that it is somehow “outside” of capitalist modernity and the commodified relations of the global literary marketplace (or indeed, any other marketplace). Instead, in a concluding theoretical discussion, I consider how the practice of drawing might allow us to think through a response to modernity’s combined and uneven development that is both materialist and decolonial at the same time. Although the former typically insists on singularity and totality, and the latter promotes a contradictory plurality, the peripheral and terrestrial realisms of Paying the Land suggest a way for theorists of world literature to find a point of methodological solidarity that is both in and against capitalist modernity’s gravitational force.

The View from Above: Peripheral Realism

Paying the Land is typical of Sacco’s work insofar as it is mainly composed of firsthand interviews with people on the ground. These include a diverse cross-section of the Dene community, from academics and priests to chiefs and local activists to government premiers and abuse survivors. In his now characteristic style, Sacco draws these testimonies together to create a comprehensive, visually reconstructed account of the region’s historical and ongoing subjection to settler colonization and resource extraction. Less typical is the relative absence of Sacco himself in this book, something its reviewers have been quick to note. Usually blustering and comical and always an unflattering caricature of Sacco himself, the character “Joe” is far less prominent in Paying the Land than he has been in previous graphic novels. (For the remainder of this article, I will use the name “Joe” to refer to Sacco’s avatar in the comic, reserving the name “Sacco” to refer to the comics artist and author of the book.) Though partly due to obligatory changes in his method—many Dene chiefs would not allow Sacco to record or even take notes during their interviews, and access to some leaders was tricky to secure—reviewers agree that Sacco’s “predominantly realist artwork [reflects an] attempt to let the Dene people speak for themselves.”Footnote 14 Clearly, the discernible reticence in Sacco’s authorial voice is a response to the people and the history that the graphic novel documents. Since their earliest contact, settlers have been representing the Dene in ways that have served the interests of extraction and profit, with catastrophic consequences for Dene communities. As Linda Tuhiwai Smith observes, the flagrant continuities between early colonial and contemporary ethnographies mean that “research” has become “one of the dirtiest words in the indigenous world’s vocabulary.”Footnote 15

Sacco is best known for his war journalism, especially Palestine (2001) and Safe Area Goražde (2003), which both “tell the story of those who by the standards of modernity have no story to tell, precisely because they have no future towards which to move.”Footnote 16 Paying the Land continues this interest in the spatial excision and enclosure of racialized groups, itself an expression of visuality’s authorization of capitalist modernity. As the comic’s account of centuries of settler colonialism in the region demonstrates, the Northwest Territories have been and remain subject to multiple waves of extractive occupation.Footnote 17 Read within Sacco’s oeuvre, Paying the Land thus implicitly compares the situation of the Northwest Territories to the Palestine-Israel and Balkans conflicts (two of the most visualized in recent history), indicating how, in all of these situations, disenfranchized communities have been enclosed and expelled from the developmental teleology of “History” through the visualization of the realities of combined and uneven development as a singularly “progressive,” developmental line.

Little wonder, then, that this colonial line repeats throughout Paying the Land. Just as Joe hitches a lift with UNRWA into Gaza in Palestine and travels along the UN “blue road” in Safe Area Goražde, Paying the Land’s second chapter begins with his journey into the Northwest Territories, “along the Mackenzie River Valley to places that are accessible to wheeled vehicles only when the ground is completely frozen over” (27).Footnote 18 Sacco marks Joe’s route across a small map of the region in a thick line of ink. The journey itself is then documented in large parallelogram frames, the architecture of the comic resembling the folds of the Ordnance Survey map that Joe grapples with in the passenger seat next to Shauna, his guide for the trip. Joe moves into the “unknown” landscape along a “known” line, one that recalls the proto-colonial routes of Joseph Conrad’s Marlow up the Congo River, or the railway tracks that first opened up the northern and westernmost regions of the Americas to colonial settlement.Footnote 19 Joe’s other job, as passenger, is to regularly speak into a handheld radio, sending out a verbal signal to warn oncoming traffic of their presence on the narrow road. By shooting sonic waves into the landscape ahead as he travels along a penetrative line, Sacco implicitly compares his own linear movement into the territory with the “sonic-like exploratory process” of seismic lines (34).Footnote 20

Sacco next includes a vertical diagram that explains “fracking, the process of extracting hard-to-access oil and natural gas by shooting a toxic mixture of water, sand, and chemicals at extremely high pressure into shale rock” (33). Sacco’s hand-drawn lines here work much like seismic ones, revealing through the vibrations of his pen—cross-hatches, shading, proximate lines—the different textures of the subsurface rock (see figure 1). The line of Joe’s route into the territory is “echoed” in the line of the fracking well, the accumulation of capital measured in the accumulating reverberations of his hand-drawn line. In forensic close-ups, Sacco explains how the “toxic mixture” is flushed into the thin layer of shale, “opening up fractures” that then bleed “oil and/or natural gas” (33). This is not how the Dene “pay the land,” but it is how settlers have made the land pay: even as Sacco details the destructive process of fracking, he concedes that “environmental red lines are contested issues in a place where resource extraction drives the economy” (35).

Figure 1 As Joe and Shauna travel up the Mackenzie River Valley, we are presented with a map of the Northwest Territories and a vertical cross-section of the land that explains the fracking process (33).

In the following pages, Sacco embeds this colonial line into a longer history of extraction, wherein the first “resources” to attract settlers to the region were furs and pelts. Sacco points in particular to Hudson’s Bay Company that, though today a retail group operating across Canada, was originally a fur trading business founded in 1670. Describing the company’s appetite for beaver skins as a “fashion,” Sacco shows how the relationship between this peripheral frontier and the capitalist world has been shaped by the rhythms of the global marketplace since the mid-eighteenth century. The dark irony, of course, is that in the twenty-first century, it is not only the natural gas and oil industries that bring people to the region, but conversely, a growing settler interest in indigenous ways of life as a behavioral “resource” for mitigating climate change.Footnote 21 Sacco even worries about his own graphic novel, which will inevitably commodify Dene testimonies for circulation on the literary marketplace: “What’s the difference between me and an oil company?” Joe asks. “We’ve both come here to extract something” (107).

Sacco reveals the colonial line’s systemic volume by drawing out its generic echoes throughout Paying the Land. He frequently shows fracking infrastructure and pipelines plunging down into the earth (37, 245), destabilizing the terrestrial surface by fragmenting the ground beneath (see figure 1). This material process, which operates along a vertical axis, then has deeper reverberations in the settler state’s systematic ungrounding of the Dene from their cultural and territorial roots. Throughout, Sacco’s drawings suggest metaphoric continuities between seismic lines, fracking lines, territorial lines, and treaty lines, which are all connected through the systemic, world-making force of the colonial line. Together, they uproot the physical and cultural grounds—conjoined and inseparable, in the Dene’s worldview—of the region’s indigenous communities.Footnote 22 The colonial line makes the violence of capitalist modernity possible by counterintuitively dividing reality from its representation, as the capacity to formulate an abstract vision of the world (in maps, plans, treaties, etc.) allows for its containment, conquest, and enclosure. By illustrating this division through the repeated application of the same genre of line, Sacco reveals how the multiple stages of settler colonialism are contained within and enabled by the same systemic logic that governs capitalist modernity as a whole.

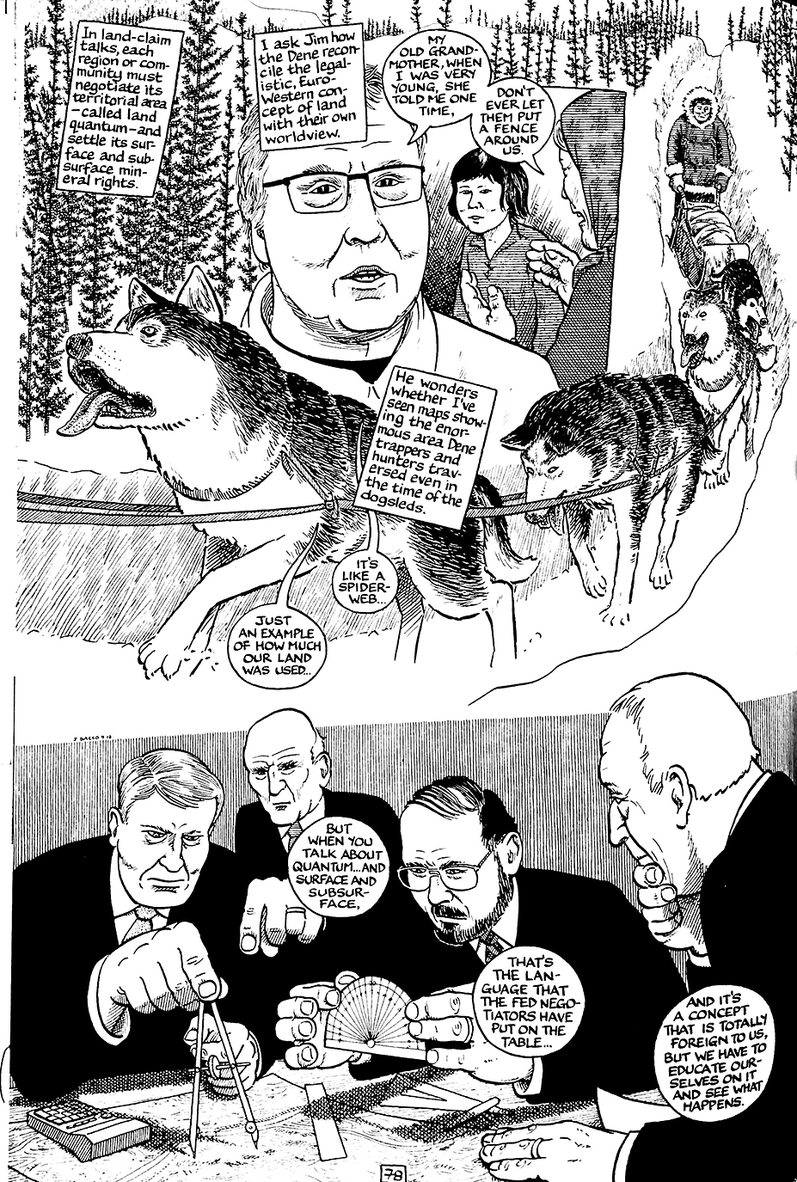

There is, however, another genre of line—a decolonial line—running through Paying the Land, one that is best illustrated by a page that appears midway through chapter 3 (see figure 2), in a section aptly titled “Divide and Conquer” (73–82). There are two kinds of maps on this page: in the upper half, Jim Antoine, an experienced indigenous politician and former chief of the Liidlii Koe First Nation, explains the vast territory once covered by Dene hunters and trappers. Crucially, the map he describes does not partition the land, but is instead composed of the winding and looping lines that the Dene “traversed even in the time of the dogsleds” and which resembled “a spider-web” (78). “What count are the lines, not the spaces between them,” writes Ingold of sketch maps, so they “are not generally surrounded by frames or borders.”Footnote 23 These lines are drawn along rather than across the land: they are terrestrial lines, capturing physical gestures and movements rather than a representation that is abstracted from the world. The territory emerges through its habitation, as the “spider-web” of journeys cut across and around one another to form a congealed surface: they do not contain or cut through the land as empty space but bring it into being through storied points of connection. What emerges is a surface marked by terrestrial presence rather than one of extraterrestrial occupation. Suitably, then, Sacco does not visualize the sketch map that Antoine describes, instead drawing images of the dogsleds themselves as they move along the carved tracks of their wayfaring lines.

Figure 2 Sacco draws the indigenous relationship with the land one as of terrestrial presence, whereas the settler relationship with the land is negotiated through abstracted representations (78).

The map in the image in the bottom half of this page is of marked contrast. With the land itself nowhere in sight, it epitomizes the genre of the colonial line. Sacco’s drawing shows a group of federal negotiators pondering over a paper map of abstract contours and grids, measuring treaty lines with various tools including a protractor, ruler, calculator, and compass—akin to what Walter Benjamin once described as “equipment” in his essay on the work of art in the age of mechanical reproduction.Footnote 24 This map authorizes the borders imposed by the settler state by rendering them through an abstract line that is drawn from a conceptual “above” (the protractor and compass literally hover above the map in this image). We do not even need to see the details of the map to recognize the power of visuality in this scene, which derives less from what the map represents (though of course that is important) and more from the act of representation itself. Visuality disguises itself as distanced and disinterested to produce an ostensibly dehistoricized representation of reality and to authorize capitalist modernity’s material effects. In opposition to this, Sacco’s comic exposes the map’s “equipment-free aspect of reality” as “the height of artifice” by repeatedly drawing the equipment of colonial modernity—fracking infrastructure, compasses, protractors, maps—into view.Footnote 25 With this, Paying the Land reveals the aboveness of colonial visuality to be far more than a rhetorical inflection or hierarchical cadence, but an abstract position that is folded into modernity as a world-breaking force, tearing apart the surface of the earth.

The colonial line’s implied aeronautics are repeated in the images of airplanes and helicopters that are also braided throughout the comic as a whole. Politicians, lawyers, corporate representatives, “loud white business people”—all are repeatedly shown arriving in the most remote regions of the Northwest Territories from above by either helicopter or plane (see, for example, 67, 71, 75, 79). Halfway through the book, the plane becomes the visual and aural shorthand for the residential school system, a state-sanctioned policy of reeducation and cultural genocide that “unmoored [the Dene] from the culture that once anchored them” (122).Footnote 26 Sacco’s terrestrial language is here purposefully chosen, not for rhetorical effect, but to convey a physical reality: “for many of those living in the bush, [the residential school system] was heralded by the sound of aircraft engines” (122; see figure 3). Importantly, like the Dene, we hear the engines before we see the plane, a sensory prioritization that again echoes the sonic waves of seismic lines and Joe’s radio callouts on his route up the Mackenzie River Valley. Sound, of course, is the one sensory input that confuses Enlightenment modernity’s separation of concepts from the material world, blurring physical effects with cognitive functions. It manifests historically in the failure of the settler state to “recognize” oral histories and cultures until they are “translated”—by missionaries, federal negotiators, and other colonial agents—into the written lines of treaties and maps, which are again further reiterations of the colonial line. Simultaneously phenomenal and epiphenomenal, sound collapses the boundary drawn by Enlightenment thinkers such as Immanuel Kant between physical and metaphysical worlds.Footnote 27 Functioning according to the same sonic logics, the decolonial line erases this division, emphasizing that when the plane “uprooted” Dene children from their culture, it did so not only figuratively, but literally too, by lifting them away from the physical land.

Figure 3 Sacco’s words, which introduce the history of Canada’s residential school system, float through the sky in anticipation of the plane that eventually swings into view (122).

Air flight typifies the colonial line, reaching its summit in the countless flight paths associated with planetary globalization. As the artist Paul Klee observes in his sustained reflection on the movement of lines, the line of flight tells a story in which technological progress allows “modern man” (gender intended) to reconcile the gap between the movement of mind through “metaphysical spaces,” on the one hand, and the “physical limitations” of the material world, on the other.Footnote 28 This tension between physical stasis and metaphysical freedom is epitomized in the “gravitational pull” of the earth itself.Footnote 29 Klee demonstrates this with a hand-drawn line that begins by curving away from its earthly point of origin before curling back in on itself, under its own weight. For Klee, this disjunction between extra-terrestrial lightness and terrestrial weight is “the origin of all human tragedy.”Footnote 30 Refining Klee’s observation slightly, we might observe that this is less a human tragedy than a tragedy of capitalist modernity itself, which has of course been inextricably bound up with the coterminous colonization of the Americas and the rise of print capitalism as well.

With his seismic lines, Sacco is able to register the systemic volume of this history. After all, he does not scatter images of helicopters and planes throughout Paying the Land as convenient symbols for settler colonial invasion. Indeed, Sacco adheres to a documentary realism, drawing the details of the spoken testimonies of his interviewees and rigorously supplementing them with other sources and archives.Footnote 31 This means that the echoes, parallels, and continuities that are folded into Sacco’s lines are not so many subjectivist or modernist techniques, but rather realist responses to the physical world he depicts. He works with a realism that, as Fredric Jameson describes in his commentary on György Lukács, recognizes “the outside world as historical process” rather than some putative object waiting to be described: the world “is already an implicit narrative and thereby holds a narrative meaning within itself that does not have to be imposed from the outside by subjective fiat or by symbolist transformation.”Footnote 32

It is in this sense that we might speak of the “peripheral realism” of Paying the Land, insofar as Sacco uses his seismic lines to reveal the systemic nature of capitalist modernity as phenomena and epiphenomena that are concretized into the reality he draws and depicts. As Jed Esty and Colleen Lye describe, peripheral realisms “invite their publics to grasp the world-system, via its local appearances or epiphenomenal effects, and not to imagine it as a foreclosed or fully narrativized entity.”Footnote 33 It is precisely these same epiphenomenal effects, the sense that the world itself is a historical process, that lead the Dene activist and academic Glen Coulthard to assert that the reality of the periphery is also the reality of the system as a whole: “Land is where anti-capitalism comes from.”Footnote 34 Against the visuality that has authorized divisive treaties, land grabs, cultural genocide, air travel, pollution, and subterranean resource extraction, Paying the Land’s peripheral realism draws the multiple phases of settler colonialism that have played out in the Northwest Territories into view as so many aspects of capitalist modernity’s systemic effects.

Drawn to the World: Terrestrial Realism

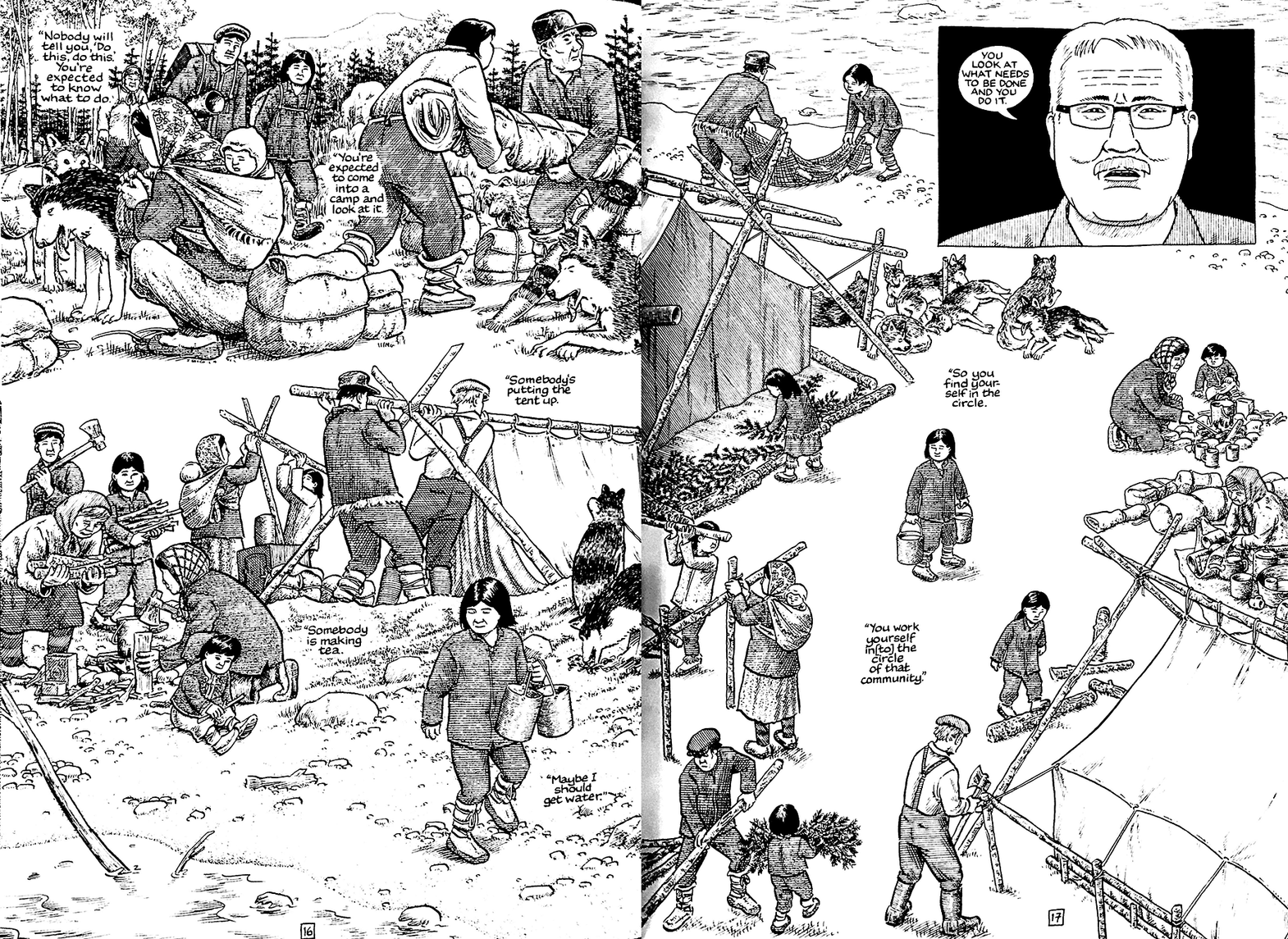

With this view of the totality in mind, it is important to note that Paying the Land does not begin with the colonial line. Instead, in chapter 1, Sacco begins the graphic novel by reconstructing the childhood memories of Paul Andrew, chief of the Shúhtaot’ine, who spent the first ten years of his life growing up in the bush. As Andrew remembers in the comic’s first words: “My grandfather tells me that when they were travelling in a moose-skin boat, that’s when I came into the world” (3). Sacco’s drawings begin “in the circle” (3, my emphasis), or on the land, rather than above it, looking down or looking in. In these opening pages, Sacco does away with frames, grids, or gutters, what I have elsewhere called the “narrative infrastructure” of comics.Footnote 35 There are no grid lines or geometric lines or pipelines or seismic lines in these pages, only the soft contours of the land, as Sacco’s graphic novel draws readers both literally and figuratively into a terrestrial point of view.

By doing away with the page’s architectural frames in this way, Sacco brings us closer to the ground of the Dene story, his hand-drawn lines attempting to emulate their precolonial relationship with the land. Importantly, this relationship is one that takes place: rather than lifting us away into the extraterrestrial plane of the colonial line, we are asked to lean in and participate in the page instead. As Andrew remembers, you must “work yourself in[to] the circle of that community” (17). This is the world not of the “apparent” but the “existent,” to use John Berger’s distinction, one that emphasizes the material conditions of labor and human survival as the “Necessity [that] makes reality real” (see figure 4).Footnote 36 As Berger writes in a particularly evocative commentary on the paintings of Vincent Van Gogh:

He saw the physical reality of labour as being, simultaneously, a necessity, an injustice and the essence of humanity to date. The artist’s creative act was for him only one among many. He believed that reality could best be approached through work, precisely because reality itself was a form of production.

Figure 4 Paul Andrew, chief of the Shúhtaot’ine, remembers the precolonial Dene way of life as late as the mid-twentieth century (16–17).

The paintings speak of this more clearly than words. Their so-called clumsiness, the gestures with which he drew pigment upon the canvas, the gestures (invisible to us but imaginable) with which he chose and mixed his colours on the palette, all the gestures with which he handled and manufactured the stuff of the painted image, are analogous to the activity of the existence of what he is painting. His paintings imitate the active existence—the labour of being—of what they depict.Footnote 37

Although I would not necessarily invite a direct comparison between Sacco and Van Gogh, the emphasis Berger places here on the physical labor of the artist is central to what I want to call “terrestrial realism” in this article. In the double-page spread of the Dene camp, the gestures and movements that are registered in Sacco’s hand-drawn lines don’t exactly repeat, but rather shadow or imitate the day-to-day labors of the Dene (“putting the tent up,” “making tea,” fetching water) that are necessary for their survival. Through the invisible gestures that nevertheless remain legible through the marks on the page, Sacco introduces not a colonial line but a terrestrial, decolonial one instead.

More importantly still, this emphasis on gesture and terrestrial presence is extended through Sacco’s hand to the reader as well. As the critical literature on processes of reading comics has demonstrated for decades, “the form requires continual reader engagement to make the images ‘speak’” and to bring the narrative system’s different correspondences and meanings into play.Footnote 38 “You’re expected to know what to do,” Andrew continues, describing the scene: “You’re expected to come into a camp and look at it” (16, my emphasis; see figure 4). Sacco frames Andrew’s words in such a way that they are imbued with two homologous meanings. Though he is speaking of the labor required upon arrival in the Dene camp, their second implication is clear enough: we readers must also work ourselves into the circle, deciphering the image without the help of gutters or grids or maps, or any other colonial lines. We must look and listen closely, not passively absorbing but participating in the story, plotting our own route through the world of the page. To again borrow a distinction from Walter Benjamin, the image refuses the “distracted mass [that] absorbs the work of art” and invites instead the person “who concentrates before” and is “absorbed by it.”Footnote 39 Insofar as these pages extend the ground of peripheral realism to include the participatory role of the reader as well, we might describe them as exhibiting a terrestrial realism that is rarely attainable on the printed page alone (“paintings speak of this more clearly than words”).Footnote 40

Indeed, though the difference between colonial and decolonial lines is most clearly illustrated in the opposing practices of sketching and map-making (the former indexing a grounded worldview, the latter claiming an abstracted view from above), it has parallels in practices of writing and reading as well. As Ingold observes, since the inception of capitalist modernity “the line of writing [has] undergone a historical transformation precisely akin to that of the drawn line on the map.”Footnote 41 Comparing indigenous cosmologies from across the world, from the Inuit to the Orochon to the Western Desert Aboriginal people, Ingold shows how oral storytelling and attendant modes of artistry and handwriting are broadly conceived as processes of line-making.Footnote 42 The same holds for pre-Enlightenment conceptions of reading in Europe, wherein the reader “would inhabit the world of the page, proceeding from word to word as the storyteller proceeds from topic to topic, or the traveler from place to place.”Footnote 43 Only with the rise of the print capitalism was writing slowly reconceived as a collection of abstract signs signifying a world beyond or “outside,” with the effect of transforming the modern reader from “an inhabitant of the page” into an overseer who “surveys the page as if from a great height.”Footnote 44 As I will argue below, this extraterrestrial positioning of the readerly gaze is epitomized in theories of world literature as a “conjecture” or “vision,” wherein the reader is not encouraged to inhabit the page of a story-world, but to assert a mastery over it instead.

Throughout Paying the Land, the printed word is mostly associated with the land treaties that, though offering the Dene an enticing promise of territorial sovereignty, ensured those claims were made on settler colonial terms and in the interests of capital. As Jim Antoine observes of the hearings that took place during the infamous Paulette Case in 1973: “The elders would talk about what happened [and the Justice of the Supreme Court, William Morrow] heard all the stories. Our stories became official … that was a big, key part for us, to have our voices heard” (67). Accompanied by an image of Justice Morrow writing down Dene testimonies in ink, the process of “being heard” described in this scene is more specifically one of “being seen”: visuality refuses to “hear” Dene voices until they are transcribed from an audible into a visual form.

It is therefore of consequence that, with the exception of the notes and acknowledgments at the back of the book, there are no printed words in Paying the Land, only Sacco’s hand-drawn letters and lines. Of course, we cannot actually “hear” the words that Sacco records in speech bubbles and caption boxes, but we can see the sonic vibrations that are registered in the scratches of his pen strokes.Footnote 45 Sacco’s pages are, to use Gayatri Spivak’s well-known distinction, more like “portraits” than “proxy” representations; or as Huda Tayob remarks of this distinction in relation to her own orthographic practice, the use of “drawing and handwriting as primary methods” render the researcher “active within the field of research, as opposed to being an ‘invisible’ author.”Footnote 46 The lines from which a drawing is comprised not only depict a world, but index the author’s presence in it, too. It is Sacco’s hand that draws the images on the page, just as it is the Dene’s hands that connect them to the land and the reader’s hands that hold the book open in their lap.Footnote 47 Against the image of the plane swooping in from above and uprooting the Dene from their terrestrial culture, the image of the hand reconnects them with the land, while Sacco’s hand connects them—and us—with the “physical reality of labour” that is required as a means of human necessity and indigenous survivance.Footnote 48

My aim in this reading is not to recourse to a deconstructionist fetishization of the spoken over the written word, nor to claim the page as somehow “outside” the enclosing lines of capitalist modernity. Rather, I want to suggest that Paying the Land renders legible a dialectical materialism in which the Dene, Sacco, and readers themselves are historically situated within capitalist modernity as a systemic whole. As Andrea Lunsford and Adam Rosenblatt have remarked of Sacco’s earlier work, Sacco’s aim is never to raise his “instrumental listening to some pure and noncommodified ideal,” but instead to insist “on the agency of his subjects even within a commodified relationship.”Footnote 49 Unlike the extraterrestrial mastery authorized by visuality, we instead find ourselves within a field of dialectical relativity where volume and mass are mutually constituted as relations and effects within capitalism’s gravitational force field. The lines of ink that show Andrew staring at us out of the page (as so many of Sacco’s interlocutors have done since his earliest comics) draw the relationship between Andrew and Sacco—and we readers, too—into a moment of encounter that is therefore both in and against colonial modernity’s systemic lines. Sacco’s drawings are “sketch maps of an encounter,” to borrow Berger’s words again, functioning more like portraits than proxy cartographies or treaty agreements.Footnote 50 Yet they also, through their peripheral realism, allow us to grasp the combined and uneven totality that visuality’s colonial lines were designed to conceal. The result is a graphic depiction not only of phenomenal vision, but of the system’s epiphenomenal reach.

The Gravity of World Literature

In the concluding sections of this article, I want to bring Paying the Land into conversation with the now decades-old “problem” of world literature. This turn to methodology may at first seem incongruous with the work undertaken so far. But it is precisely by flipping the conventional ordering of the “reading” and “methodology” sections of this article that we might come to view world literature—and indeed, the dynamic field of capitalist modernity itself—through Sacco’s literary world, as opposed to positioning the theory before or “above” the text as some predetermined symptom or line, as is sometimes practiced. So doing not only repeats Mirzoeff’s insistence that the right to look, here taking place within the ground of the text, always precedes visuality. It also allows us, as readers and critics “on this side of the text,” to historicize the moment “in which we ourselves are writing and reading” and to remain cognizant of our own standpoint within the totality of the world-system that Sacco’s peripheral realism brings into view.Footnote 51

We might identify two “waves” of world literature to help us with this task: the first, of Pascale Casanova, David Damrosch, and Franco Moretti, among others, around the turn of the twentieth century; the second, of the Warwick Research Collective (WReC), Alexander Beecroft, Debjani Ganguly, and Pheng Cheah, all of whom published key texts in 2015 and 2016. Lines are central to every one of these approaches, though with the exception of the WReC, they almost always restrict themselves to only one genre of line. On the one hand, there are those that limit their analysis to the decolonial line alone, with the effect of losing sight of the capitalist system that reshapes and overturns the ground beneath its feet. For example, we might consider Pheng Cheah’s attempt, in What Is a World?, to argue for “a normative understanding of the world [that] leads to a radical rethinking of world literature as literature that is an active power in the making of worlds”, yet which ends up collapsing dialectical analysis into a singular line that affords only a restrictively situated sight and sense of the world.Footnote 52

On the other hand, there are those that apply only the genre of the colonial line. For example, built into Damrosch’s well-known definition of world literature as a text that has “taken off” from its “culture of origin,” traversed national borders, and arrived somewhere else, is an imperial line that is interested only in points of departure and arrival, and of production and consumption, at the expense of the journey itself. “It is not so much a development along a way of life as a carrying across,” to return to Ingold’s distinction, wherein the arrival of a text “marks a moment not of tension but of completion.”Footnote 53 In this view, the world of world literature is delimited, circumscribed, and occupied as abstract space rather than grasped as a capitalist matrix of combined and uneven dialectical relativities constantly shaping and reshaping the ground of our terrestrial world.Footnote 54 Meanwhile, though his work is influenced by Immanuel Wallerstein, Franco Moretti’s notion of distant reading similarly seeks to eschew what I have elsewhere called “the weight of world literature,” using technologies of abstraction and visualization to cut ourselves free from the ground of literary materials as well as our own historical ground.Footnote 55 The effect is to create a scientistic vision of abstract lines that construct a cartographic visualization of literary worlds.Footnote 56 It is not only methods of “close reading” that are lost in this visualization, but more particularly our own relationship with—and our implication in—both literature and the world.

It has been some time since Edward Said made the point, in The World, the Text, and the Critic, that “the flight into method and system” risked “predetermining what [its proponents] discuss, heedlessly converting everything into the efficacy of the method, carelessly ignoring the circumstances out of which all theory, system, and method, ultimately derive.”Footnote 57 Against such extraterrestrial pursuits, Said always emphasized the “situated” nature of criticism, and his work is littered with “earthly and worldly valences” that come together to comprise the ground of his “terrestrial humanism.”Footnote 58 He anticipated with remarkable acuity world literature’s typically modern ambition to take flight, which manifests here in the turn to visualities that abstract the ground of literary texts into colonial lines. Functioning as visuality, world literature finds itself able to see only what it already knows and controls, prioritizing sight as a method of territorial occupation over the terrestrial habitation of the world.

In a concerted attempt to mark out a more explicitly materialist and interpretive method in this context, the WReC advance what has become an increasingly widespread world-systems approach that takes “‘world literature to be that body of writing that registers in various ways, at the levels of form and content, the historical experience of capitalist modernity.”Footnote 59 The world is here conceived as the totality of the capitalist world-system, which disaggregates the earth into cores, semi-peripheries, and peripheries that together coexist under the sign of a singular modernity.Footnote 60 World-literature, with the hyphen, is thus a model that holds the tension of abstraction and specificity, above and below, together at once, grasping the spatiotemporal granularity of global capital as it is marked out through a dynamic model of combined and uneven development. We might say that this dialectical method follows the dual movement of Klee’s modern line, taking flight into the conceptual totality before curving back under gravity’s pull toward the concrete hierarchies and divisions that are constantly inscribed and reinscribed into the surface of the earth.

With this brief theoretical context in mind, I want to suggest that Sacco’s seismic lines—which are able to capture the systemic totality driving centuries of extraction in the Northwest Territories, and at the same time, to register a decolonial line that is terrestrial and bound to the world—might help us to grasp what I will call here the gravity of world literature: the dynamic singularity of global capital that draws not only authors and texts but also readers and critics into its gravitational orbit, with the effect of conditioning but also enabling encounters through literary worlds. When we introduce the decolonial line that takes place within and against the matrix of capital’s systemic lines, we can begin to conceive of reading itself as a way of drawing ourselves into the world. The result is to take and make a place within the world-system that moves toward a decolonial force, emphasizing points of methodological overlap and solidarity rather than perpetual antagonism, differentiation, and divorce. As Jameson suggests, “Intellectual work in our time does not mean converting to a single code and trying to hammer it into people but rather being able to address the nuances that exist between codes.”Footnote 61

This is why I suggest “terrestrial realism” as a way through to this ground: it takes, on the one hand, Said’s terrestrial humanism, with its emphasis on human autonomy insofar as it operates as a collective force, and on the other, combines it with peripheral realism and its ability not only to grasp the totality, but to breath “new life into the critical and aesthetic project of apprehending the real [and thus of questioning] global capitalism’s status as a permanent fact.”Footnote 62 Which is to say, terrestrial realism, like peripheral realism, allows us to recognize the epiphenomenal effects of capital as a systemic force. However, against the tendencies of reification to objectify that system into a closed if internally differentiated loop, it instead keeps the dialectical method open by maintaining a humanist emphasis on our collective, future-oriented force. As I have suggested here, the graphic novel, which demands a particularly participatory form of interpretive reading, might be one such place where terrestrial realism’s view of the systemic whole—one that includes the reader in its model of capitalism’s gravitational field—can be most obviously grasped.

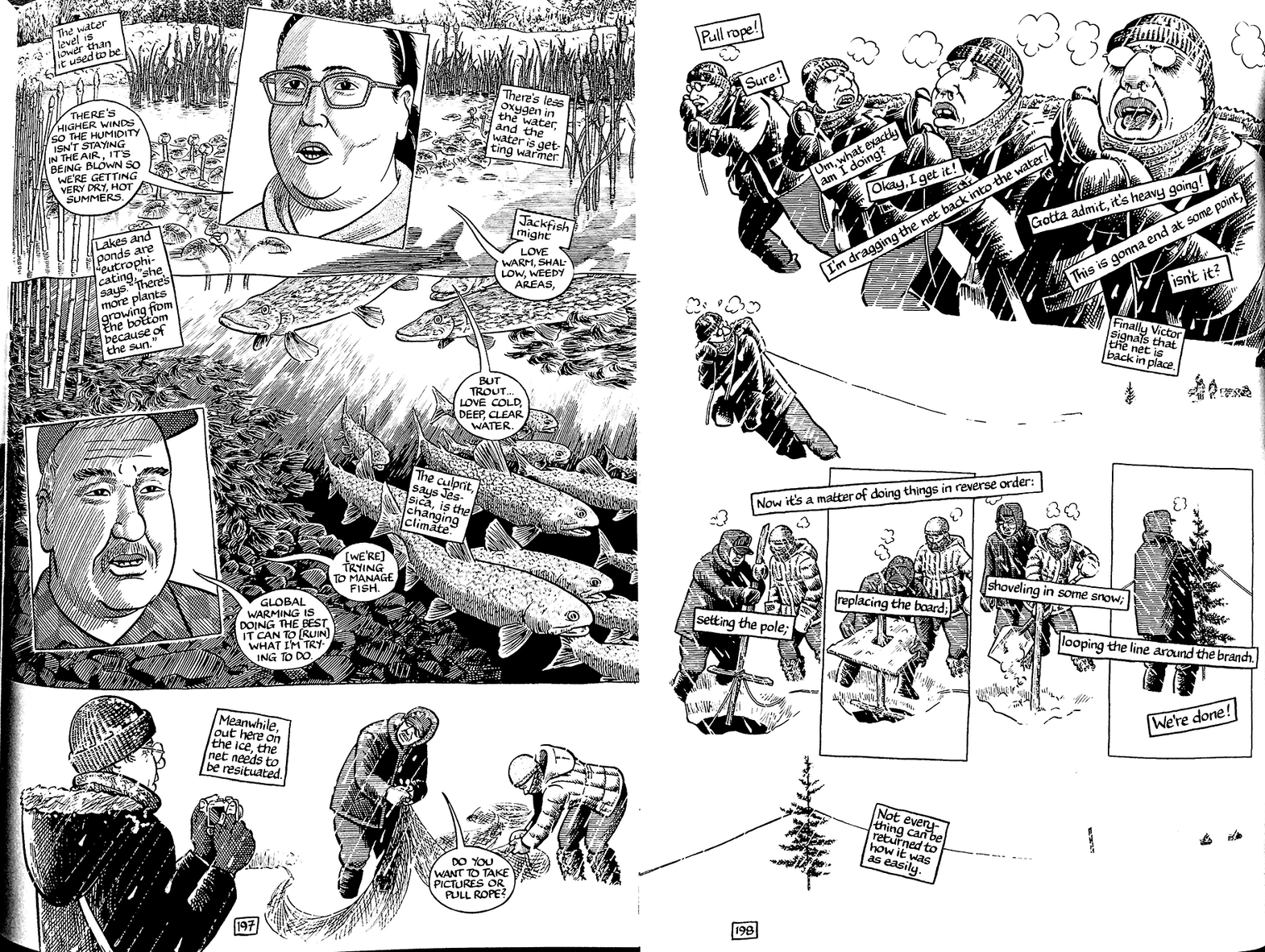

Conclusion: Van Gogh’s Lasers

By way of conclusion, I want to return these theoretical observations to a final, brief reading of an illuminating scene that occurs some two-thirds of the way through Paying the Land. Joe is in Trout Lake, one of the most remote regions he visits on his tour of the Northwest Territories. The first page shows Victor and Jessica, two local Dene, retrieving their fishing nets from beneath the frozen lake and explaining the consequences of a changing climate for marine life as they work (197; see figure 5). Joe looks on, holding up his camera to snap a photograph, while Victor and Jessica prepare to return the nets to the water. Suddenly, Victor turns to Joe and asks: “Do you want to take pictures or pull rope?” Joe promptly drops the camera previously held in both his hands, before grabbing the rope and dragging “the net back into the water” (198). Rather than observe from a distance through the viewfinder of a camera, he instead grabs a line with his hands and draws it across the page. When we observe the two pages together, the horizontal grid lines that divide the former page and hold it up to our gaze are, in the latter, tugged apart by Joe himself. Joe’s heavy panting emphasizes the manual labor involved in this reorientation, while his parting comment—“not everything can be returned to how it was as easily”—threads the singular fishing line back into the systemic tapestry that his peripheral realism has brought into view.

Figure 5 Joe drops his camera and grips the net with his hands, dragging—or drawing—a line across the page (197–98).

It is tempting to read this sequence as simply a callout to Sacco’s apathetic audience, who are reading their glossy, commodified graphic novels in the post-industrial centers rather than the peripheries of capitalist modernity: get up, take action, do something other than sit and stare. No doubt such a reading is partly in place, and it is supported by Sacco’s unflattering self-presentation as a bit of a hack, somehow detached from or disinterested in the world he observes and in pursuit of nothing more than a quick sound bite to ensure his commercial success. However, although this is a long-running theme in Sacco’s earlier comics, it is not what is most interesting here. Instead, we might note that in the second page of this sequence, there is a subtle breaking of the fourth wall, as Joe grabs and handles the architecture of the comic’s page and Sacco draws attention to the strokes of his pen; and yet, even as this fourth wall is broken, the lines remain actual fishing lines, part of the graphic novel’s “real” world. Through this visual paradox, Sacco folds the modernist techniques for which comics are well known back into the reality of his graphic novel’s diegetic world. In so doing, Sacco seems to raise Jameson’s speculation, highlighted by the WReC in their discussion of peripheral realism, that “the ultimate renewal of modernism, the final dialectical subversion of the now automatised conventions of an aesthetics of perceptual revolution, might not simply be … realism itself!”Footnote 63

No doubt what is registered in this additional turn of the dialectic is the now widely acknowledged systemic challenge of climate breakdown to global capital. In the age of the Capitalocene, capital operates as a “system of power, profit, and re/production in the web of life,” more evidently turning the world itself into a historical process than ever before.Footnote 64 As they speak to Joe of the warming waters of Trout Lake and the accumulation of micro-plastic debris in its fish, it is precisely this process that Sacco’s Dene guides, Victor and Jessica, seem to describe. With this in mind, we can see how the second page performs metaphysical work, suggesting less that we leap into action (though that is certainly implicit) and more that human action has already altered our “real” world, transforming it into historical material and imbuing it with narrative meaning and symbolic form. This, again, is Paying the Land’s terrestrial realism, one that inculcates readers into the force field of capital’s voracious accumulative metabolism and brings into view what Treasa De Loughry, in her discussion of capital’s gravitational force, calls the “‘kernel’ of emancipatory collectivity.”Footnote 65

Sacco is upfront about his laborious commitment to meticulous detail in his realist drawings: “I’m not going to caricature a fish,” he remarks; when drawing a Caribou, “looking at it closely, you’re thinking of the anatomy of it and how to make the fur right.”Footnote 66 Elsewhere he has emphasized the physicality of his hand-drawn lines—“I’ve never considered myself a particularly good artist, I kind of bludgeon my way through the page”—and critics have noted “the richness of [Sacco’s] haptically charged surfaces” and the way they call “attention to the reader’s embodied interpretive processes.”Footnote 67 But these readings have too often attached Sacco’s realism to an ethics of embodied and affective vulnerability, rather than reading for its material reality effects. By highlighting his peripheral and terrestrial realism, I have tried to show how Sacco draws the mutually constituting—if unstable—standpoints of both his readers and interlocutors into capitalist modernity’s singularly combined and uneven ground. We might return briefly to Berger’s commentary on Van Gogh for a final grasp of this process:

Once, long ago, paintings were compared with mirrors. Van Gogh’s might be compared with lasers. They do not wait to receive, they go out to meet, and what they traverse is not so much empty space, as the act of production. The “entire world” that Van Gogh offers as a reply to the vertigo of nothingness is the production of the world.Footnote 68

Sacco’s seismic lines work similarly, not as mirrors but as lasers, creating a force field in which we not only see but feel the gravity of world literature, and which implicates us as readers in the historical production of the world. Against the “vertigo” of visuality’s view from above, terrestrial realism grounds us in the dialectical composition of this world, which is also Sacco’s world, the Dene’s world, and our only world.