8.1 Introduction: what is SDG8 and how can health policy contribute?

Health is wealth. As the introductory chapters have shown, decent work and economic growth benefit greatly from a healthy population. However, the possible contribution of health policy to SDG8 goes beyond its contribution to population health because of the massive economic and employment footprint of health care and related systems. This chapter explores how health policy can help support progress towards SDG8 (creating decent work and economic growth), in light of the health and care sector being a major source of employment globally. Although health policy also contributes substantially to economic growth by improving the health and therefore productivity of the population, this is discussed elsewhere in this volume and is not covered in this chapter. We include a case study which explores health policy actions taken in Romania to improve attraction, recruitment and retention of health and care workers (HCWs). Romania is chosen as a case study as it highlights a number of common health and care workforce (HCWF) challenges experienced by countries globally. These include chronic shortages of HCWs that have been exacerbated by substantial outward migration, maldistribution in rural and remote areas, and insufficient skillmix to meet population health needs. With the health and care sector a major employer globally, efforts to strengthen the health workforce can support progress towards meeting SDG8. While not the primary focus of this chapter, it is important to note that actions to strengthen the HCWF can also help promote better health and wellbeing for all (SDG3) and better educational opportunities (SDG4). Moreover, positive outcomes related to employment and education are likely to especially benefit women (SDG5), who are estimated to make up two-thirds of those employed in health and social care globally (Reference Magar, Gerecke, Dhillon, Buchan, Dhillon and CampbellMagar et al., 2016).

8.2 Background

SDG8 calls for countries to “promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all”. Health and long-term care and broader industries affected by health policy are major employers that can affect their own and others’ labour market prospects. The HCWF is estimated to directly account for 3.4% of total global employment, ranging from 1% of total employment in low- and middle-income countries and up to 10% in high-income countries (WHO & ILO, 2022). Some industries related to health care, such as research, higher education and pharmaceuticals, are also important contributors to employment in many countries (see also Chapter 9).

Health and long-term care is a well known driver of employment growth. This is for a variety of reasons, but one is simply that it is a high-touch service sector that is difficult to make more efficient. Many consultations with health care professionals or contacts with social care workers are provided on a one-on-one basis, and making them handle more patients in a day is likely to reduce the quality of their work and comprehensiveness of their services. Even clearly efficiency-increasing options such as telehealth consultations can turn out to have potential and unpredictable quality and cost implications.

Thus, due to factors like an expanding sector, changing population demographics, and the necessity to maintain high standards of care, health and care sector employment tends to grow. This tendency for employment growth is known to economists as Baumol’s disease (Reference BaumolBaumol, 1967). While growth and industry change make cost containment difficult, it does mean that growing health systems increasingly make up a large portion of the economy, therefore becoming increasingly important employers across countries. Greater numbers of people thus depend on health care incomes and health care system employment standards. Consequently, this employment growth and subsequent power means that health and care employers will have a large impact on a substantial portion of employable individuals through health sector decisions, governance and overall wages.

The health and long-term care sector can also be an important potential contributor to reducing employment-related inequalities (see also Chapters 7 and 10). Health care providers are often geographically dispersed across diverse localities, which means that health employers might be one of the few, and amongst the most important, employers in poorer areas. Health care and related sectors also employ people at a wide range of skill levels, formal education and salaries, such as highly trained specialist doctors, home health aides, administrators, hospital porters and people without extensive educational credentialling. In addition, health care and related sectors in most countries employ a large number of women, migrants and minorities, shaping prospects for people across the society. (WHO & ILO, 2022).

Finally, health care is responsive to the state because of substantial public/parapublic funding and extensive regulation. While changing health systems and implementing even simple policies is notoriously difficult, there is still a variety of tools such as financing, regulation and professional standards that can be used by policymakers.

8.3 Causal pathways

Health policy can contribute to attainment of SDG8 through the health and care sector’s role as a major employer (Fig. 8.1). SDG Target 8.2 calls for countries to achieve higher levels of economic productivity, in part by focusing on “high value-added and labor-intensive sectors”. SDG Targets 8.5, 8.6 and 8.8, meanwhile, focus on reducing employment-related inequities for all women and men – including migrants, people living with disabilities and young people – by promoting full employment, decent work with equal pay for equal value, and safe and secure working environments.

Fig. 8.1 Causal pathway mapping for SDG8: the health and economic outcomes, as influenced by governance mechanisms used by the combined economic and health sectors

As highlighted above, the health and care sector is highly labour-intensive as well as being a major employer of women, migrants and young people globally. Health sectors can therefore play a key role in meeting SDG targets of promoting decent jobs and reducing employment-related inequalities, consequently driving productivity and economic growth. The co-benefits are both direct, through the impact of health employment on employees, and indirect, through the impact of the health sector’s actions on the broader labour market.

Indirectly, health policy can affect local and national economies because of the size and diversity of the HCWF. In local labour markets they can influence overall wage-setting and employment conditions, both as a workforce model and by competing with other businesses for talented staff. Unionization also typically builds outward from areas of labour strength, so a unionized health care sector can be a linchpin for broader and potentially beneficial social partnership. Moreover, the health sector indirectly has a significant multiplier effect on the overall labour force and economy, by creating and supporting jobs in industries that drive innovation such as in pharmaceuticals, digital health technologies, research and development, and manufacturing (for example, medical equipment, physical infrastructure, etc.). While there is limited evidence on multiplier effects in low- and middle-income countries, multiplier effects in high-income countries are substantial. In Spain, for example, the health technology industry employed 28 500 people in 2020 and generated a turnover of €8.8 billion (Reference Bernal-Delgado and Al TayaraBernal-Delgado & Al Tayara, 2022). In France, digital health start-ups were estimated to have an annual turnover of €800 million in 2019, rising to a projected €40 billion by 2030, while the medical devices sector had a turnover of €30 billion in 2019 and generated 90 000 jobs (Reference Or and Al TayaraOr & Al Tayara, 2022). Given that health and care and related industries are both high value added and labour-intensive, the surrounding industries not only have inherent value but also can contribute to the broader attainment of SDG8’s goal of decent work and economic growth.

Directly, the functions within an employment system of hiring, pay, job design and career paths of health and care-related employers can contribute to reducing various inequalities and provide good jobs. Hiring and promotion systems can reduce inequalities by eliminating discriminatory practices that lead to less well-paid jobs for women, people with disabilities and other racial, religious and ethnic minorities. Reducing discriminatory pay differentials within jobs and discriminatory job classifications (for example, putting women into job categories with lower pay and worse prospects) can contribute to equality. Having standardized working conditions, transparent pay scales, formalizing informal jobs – particularly in long-term care – and tackling negative stereotypes around marginalized groups can further help promote equality. Other tasks that can use health policy to help reduce employment-related inequalities can be as distinctive as diversifying medical school admissions and hiring in order to have doctors who better represent the population at large, creating permanent and stable positions for traditionally precarious workforces in areas such as care for older people. Developing coherent career paths and equal opportunities for further training and promotion can enable upward mobility within organizations for those who might find fewer opportunities to rise in the broader economy.

All of this will have an impact on education, as to train a workforce that empowers and enables those historically overlooked will entail equal educational opportunities for all individuals (SDG4). Efforts to promote equal opportunities necessarily need to start early, by encouraging women and ethnic minorities to consider careers in STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) (WHO & ILO, 2022).

Creating decent work for all relies on creating conditions that promote a healthy work environment, a good work-life balance, and stable and fair employment conditions. Some effective health policy instruments to achieve these aims include ensuring fair remuneration, flexible working, safe staffing levels, limits on working hours, providing childcare and improving workplace occupational health and safety, among others (WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2022). Creating and maintaining systems and policies that promote training and promotion paths and offering lifelong training are also important to allow employees upward occupational mobility if desired.

Overall, there are vast opportunities to use health policy to create employment and decent work for all within the health and care sector, and a substantial body of literature on education and management exists that proposes and tests interventions and policy ideas. However, these policy options are often not used effectively or at all, and many inefficiencies continue to persist in relation to the health and workforce globally. For example, it has been estimated that worldwide women wage earners in the health and care sector earn almost 20% less than men, with women overrepresented in lower paid occupational categories and men in higher paid occupational categories (WHO & ILO, 2022). Moreover, many countries are experiencing major shortages of HCWs and have insufficient skillmix to meet population health needs. In part, this is due to failures to enhance attraction, recruitment and retention of HCWs by improving employment and working conditions, including remuneration and career opportunities. Failure to address these inefficiencies in the HCWF will not only undermine efforts to meet SDG8 but will curb progress towards universal health coverage and achieving good health and wellbeing for all (SDG3).

8.4 Governance and politics: conceptual issues

Governance is how societies make and implement decisions. The contribution of health policy to most SDGs requires a great deal of intersectoral collaboration and governance. This is also the case for SDG8. Ensuring the sustainable supply and employment of HCWs requires the health and care sector to work together with other sectors, including the education, labour and finance sectors, although this is not always achieved in practice. A range of cross-sectoral governance actions, such as regulating and accrediting educational institutions, policies on access to the health labour market and setting general conditions of work and employment, all play a key role in shaping the HCWF (WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2022). Furthermore, departments of social protection and social affairs can play a key role in developing polices to reduce horizontal and vertical gender segregation (WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2022).

Matching and maximizing the contribution of health policy to SDG8 nevertheless primarily requires changes within the health sector. Health policymakers generally have access to key policy tools for improving employment and working conditions: sectoral bargaining systems, labour contracts, regulatory and inspection standards, accreditation and credentialling, and civil service rules. The governance of the health sector is what matters, including the range of available policy tools and rules for making decisions. The involvement and influence of the state, however, vary considerably between countries. A centralized national health service, for example, may generally have a larger regulatory and enforcement role than a fragmented health service with a large private sector, where regulation and enforcement might be difficult or not feasible.

The politics of attaining SDG8 through health are challenging because they frequently involve additional costs. Workplace health and safety measures will often have immediate and visible costs (equipment, slower working) even if they lead to longer-term benefits by reducing injuries, promoting mental health and ensuring quality and safety. Efforts to improve hostile workplace climates (for example, by addressing bullying or sexual abuse) can be difficult and may alienate powerful people who enjoy, and might have created, that climate. More equal pay and conditions will require either additional funds, redistribution from other health care budget areas or redistribution of expenditure away from the best-paid towards the worst-paid – for example, from the clinical workforce to the non-clinical workforce. In turn, this means confronting entrenched interests and, in many cases, constraints imposed by cost containment. Those entrenched interests can include unions and incumbent employees with strong legal protections if they do not feel that they or their members would benefit from changing employment conditions (a problem of labour market dualism that can entrench inequality between protected workers in unionized positions and unprotected workers without unions). They can also include outsourcing firms. In many cases, services that employ many workers who are the victims of discrimination, such as facilities maintenance and home health care, are outsourced to private firms to reduce costs. With private health care providers profit-focused, they are often unwilling to improve their workers’ salaries and working conditions. The employees might be both precarious and invisible to health policymakers, but the employers are likely to be well organized and politically represented. Finally, the effects of spending more in health affects other public employees and might create pressure to increase salaries in other sectors.

There are also strong arguments to be made against being a better employer than is strictly necessary. Efficiency can appear to be improved in many cases if there are fewer employees, they have more work, or their workplace does not adhere to the highest standards of health and safety. Why should (often publicly financed) systems pay more than they must to recruit staff? Against this way of thinking, it is clear that there are long-run benefits to being a better employer. This is the basis of the economic concept of the “efficiency wage” (Reference AkerlofAkerlof, 1984; Reference Akerlof and YellenAkerlof & Yellen, 1986). Above-market wages are paid to improve productivity and reduce the rates of sick leave by having a happier, more stable workforce that requires less oversight, can be trained to higher levels, and is not subject to all the cost and quality problems associated with turnover.

In many cases, the result is that healthcare workforce becomes a low-salience, high-conflict area of policy, wherein policymakers have limited incentive to start politically unrewarding arguments about expensive policies with professionals, unions, companies or managers. Politically, then, who can raise the salience of the issues incorporated in SDG8 and perhaps formulate solutions that gain agreement? The clearest answer is organizations that represent the groups who stand to benefit the most: unions, civil society organizations and advocates representing women, workers and minority groups who are the subject of discrimination. Broader coalitions in support of health policies that support SDG8 might include local governments, patient and community groups, and professional organizations. Publicized scandals (such as deaths among care workers and the older people they served during the COVID-19 pandemic) can sometimes lead to change.

It will always be difficult to avoid conflict when the subject is pay and conditions of publicly financed work, but increased budgets can ease distributive conflicts. It is not an accident that Agenda for Change, which regraded and shifted pay scales across the English NHS, happened at a time of substantial budget increases. These public budget increases meant that differentials at the bottom could be reduced while still increasing pay at the top of the income scale. Times and circumstances, like those created by the Agenda for Change, of increased health expenditure create an agreeable environment in which to push health systems towards supporting the goals of SDG8.

8.5 Country case study: tackling health worker shortages and maldistribution in Romania

As demonstrated, the health sector can play a key role in promoting economic growth, employment and decent work for all. Maximizing the contribution of the health sector to SDG8 nevertheless requires policy actions to ensure a sufficient supply, efficient employment, and equal geographic distribution of HCWs. In this case study, we provide an overview of policy actions taken in Romania to address health workforce shortages and other workforce deficiencies such as insufficient skillmix, by tackling issues related to recruitment, retention, maldistribution and international mobility of health workers. While Romania has experienced chronic health workforce shortages since the 1990s, this case study focuses on recent policy actions that were undertaken to address a substantial increase in outward migration of health workers after the country’s accession to the EU in 2007. It should be noted that the recent, or in some cases ongoing, implementation of these reforms means that their full impact cannot yet be assessed.

8.5.1 Romania has a chronic shortage and insufficient skillmix of health and long-term care workers especially in rural and deprived areas

Romania has a highly centralized, Social Health Insurance-based health system. Health spending increased by approximately 10.3% annually between 2015 and 2019 but remains among the lowest in the EU when measured as a share of GDP (5.7% in 2019) or per capita (EUR) (OECD & European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, 2021). The health sector in Romania accounted for approximately 5% of the economically active population (over 15 years of age) in 2018, making it an important source of employment in the country (Eurostat, 2020). The country has nevertheless faced long-standing issues over health worker shortages, in particular in rural and deprived areas. The number of practising physicians per capita (3.1 per 1000 population) in 2018 was the third lowest in the EU. The number of nurses (7.2 per 1000) was also below the EU average (8.2 per 1000) (OECD.stat, 2021). Alongside a shortage of GPs, the COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted acute shortages among intensive care unit (ICU) physicians, nurses and other specialized health care staff and carers. Persistent health worker shortages and maldistribution have contributed to geographic disparities in access to care and inequalities in health outcomes for vulnerable groups, and have had a deleterious impact on quality of care (OECD & European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, 2021; Reference Vlaˇ descu, Scîntee and OlsavszkyVlaˇ descu et al., 2016).

Prominent causes of health and long-term care worker shortages in Romania include low salaries compared to other sectors, limited career development opportunities, poor working conditions, a gap between required competencies and working opportunities – partly due to lack of modern technologies – and insufficient recognition and social status (Reference Galan, Olsavszky, Vladescu, Wismar, Maier and GlinosGalan, Olsavszky & Vlaˇ descu, 2011). Workforce challenges were further exacerbated by responses to the economic crisis in 2009/10, which saw budget constraints placed on hospitals’ staffing capacity and a recruitment freeze and salary cut of 25% introduced in the public sector (Reference Suciu, Popescu and CiumageanuSuciu et al., 2017).

These issues have seen young people increasingly opt for more attractive careers in other sectors, while a significant number of health professionals have left the public sector or migrated abroad (Reference Vlaˇ descu, Scîntee and OlsavszkyVlaˇ descu et al., 2016). The challenge of outward migration increased dramatically after 2007, when EU accession and the associated rights of free movement and mutual recognition of qualifications provided new opportunities to seek better remuneration, working conditions and training opportunities in other countries. While accurate data on migration trends are limited for most professions, it is estimated that from 2007 to 2013 approximately 14 000 physicians left to work abroadFootnote 1 (Reference 147Paina, Ungureanu and OlsavszkyPaina, Ungureanu & Olsavszky, 2016), with France, Germany and the UK popular countries of destination (Reference Williams, Jacob and RakovacWilliams et al., 2020). In the long-term care sector, the exact number of carers who have migrated is unknown due to the scarcity of data.

8.5.2 Tackling health worker shortages in Romania is a political priority

Addressing shortages and maldistribution of health workers has become a political priority in Romania owing to concerns over the impact on health and quality of care. Accordingly, an objective was included in the “National Health Strategy 2014–2020: Health for Prosperity”, to implement sustainable human resources for health strategy. A National Action Plan for Human Resources was later developed in 2016, with agreement from policymakers, labour unions and professional associations. The primary aims are to strengthen health workforce governance, data flows and research evidence to improve planning and policymaking (Reference Ungureanu and Socha-DietrichUngureanu & Socha-Dietrich, 2019). A Human Resources for Health Centre was also created in 2017 by the Ministry of Health to improve planning and management for the medical workforce and to support the return of physicians who have migrated. A national registry of health professionals in the country is currently under development (Reference Ungureanu and Socha-DietrichUngureanu & Socha-Dietrich, 2019).

The Romanian government has also taken on responsibility for improving the professional status of health workers by increasing salaries and developing performance assessment criteria and career pathways. As part of the vision for the Government Programme 2017–2022, a “motivating salary package” for health professionals was included as a key reform to reduce the number leaving the public health workforce (Reference Scîntee and Vlaˇ descuScîntee & Vlaˇ descu, 2018). Alongside addressing low salaries, these reforms also explicitly aimed to boost employment and the economy. The Committees for Labour and Social Protections, and Budget, Finance and Banks within the Chamber of Deputies approved small salary increases for health professionals in 2016, with commitments for further increases and improvements to working conditions by 2022 (Law 153/2017). While the vision to raise salaries gained broad political support and was seen as justified, it created some political conflict with the opposition party. The criticism pointed to a significant increase in Romania’s budget deficit, ultimately undermining the country’s fiscal sustainability. This would be especially true if other public sector workers asked for a salary increase (Table 8.1).

Table 8.1 Political importance and conflict: the context of policymaking and implementation of reforms to increase health worker salaries

| Conflict | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Medium | High | ||

| Political importance | High | x | ||

| Medium | ||||

| Low | ||||

The limited initial increase in salaries and the phased approach to improvement were not deemed acceptable by health professionals and their trade unions, leading to protest rallies and strikes supported by the public (Reference Scîntee and Vlaˇ descuScîntee & Vlaˇ descu, 2018). Successful negotiations between the government and representatives of health workers ultimately led the government to amend Law 153/2017 through an Emergency Ordinance in December 2017 to bring forward salary increases for physicians, nurses and other health workers in the public sector from 1 March 2018 (Reference Scîntee and Vlaˇ descuScîntee & Vlaˇ descu, 2018). Upon implementation, the average salary of a junior doctor increased by approximately 162%, and the average salary of a senior physician by 131%. While data on the impact of this reform are not yet available, the Ministry of Health has suggested there are early signs of more Romanian physicians expressing an interest in returning home to practise (Reference Scîntee and Vlaˇ descuScîntee & Vlaˇ descu, 2018). Nevertheless, the reform only targeted hospital-based doctors and has not addressed low salaries for GPs, which may contribute to a weakening of primary care and exacerbate inefficiencies in the health system in the future.

Other efforts to boost recruitment and retention of health professionals and to enhance skillmix include strategies to improve career development opportunities and working conditions. For example, specialization options for nurses have also been expanded through Order 942/2017, to include new disciplines such as paediatrics, psychiatry, oncology and community care, among others (Reference Vlaˇ descu and ScînteeVlaˇ descu & Scîntee, 2017). The Ministry of Health also took steps to reform residency options for medical graduates to reduce physician shortages in rural areas and for certain specialties. Under the reforms, graduates must work in a particular location or a particular specialty with shortages for the time of their medical training. However, while formal evaluations have not been conducted, some preliminary evidence suggests that poor management and lack of enforcement of contracts has seen a high proportion of residents dropping out of residencies early (Reference 147Paina, Ungureanu and OlsavszkyPaina, Ungureanu & Olsavszky, 2016; Reference Ungureanu and Socha-DietrichUngureanu & Socha-Dietrich, 2019).

8.5.3 Responding to health worker shortages requires international initiatives and cooperation

International actors have also played an important role in helping to strengthen Romania’s HCWF. In particular, the EU has launched a number of initiatives to help Member States improve workforce planning, training, development and retention. For example, a number of measures have been implemented with support from European and Structural Investment Funds (ESIF) to: increase competencies in certain medical practices such as minimally invasive surgeries, oncology and endocrinology; provide more training opportunities; enhance digital capacities; and increase access to modern equipment (OECD & European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, 2021). The EU’s Recovery and Resilience Facility initiated in 2021 in response to the COVID-19 pandemic has also provided funding that can be used to improve education systems and skills of health workers (Reference Williams, Maier and ScarpettiWilliams et al., 2022). Under this initiative, Romania’s Recovery and Resilience plan has been granted funding to improve “capacity for health management and human resources in health”. Specific measures that will be taken to meet this objective include the preparation of the Strategy for Human Resources Development for 2022–2030, training for health workers, and the establishment of the National Institute for Health Services Management (Reference Scîntee and Vlaˇ descuScîntee & Vlaˇ descu, 2022).

International cooperation and initiatives have also been put in place to help manage the international migration of health workers. A significant global effort in this area includes the development and adoption by WHO Member States in 2010 of the “WHO Global Code of Practice on the International Recruitment of Health Personnel” (WHO, 2010). The Global Code established “voluntary principles and practices” to reduce active recruitment of health workers from low- and middle-income countries facing critical shortages, while encouraging countries to strengthen their domestic workforces (WHO, 2010). To support monitoring of the Code in Europe, the OECD, WHO-Europe and EUROSTAT have worked together to extend data collection on health worker mobility to the entire region. It is important to note that the Code recognizes that international migration can be of benefit for source and destination countries if managed properly, for example, through the use of bilateral country agreements (Reference Williams, Jacob and RakovacWilliams et al., 2020). Romania itself has signed 11 bilateral agreements, although many of these pre-date the existence of the Code (for example, with Germany in 2005 to manage the recruitment of nursing aides). The impact of these bilateral agreements overall has not been monitored, making their effectiveness unknown.

8.5.4 Multiple intersectoral governance structures and governance actions have been used to respond to health worker shortages

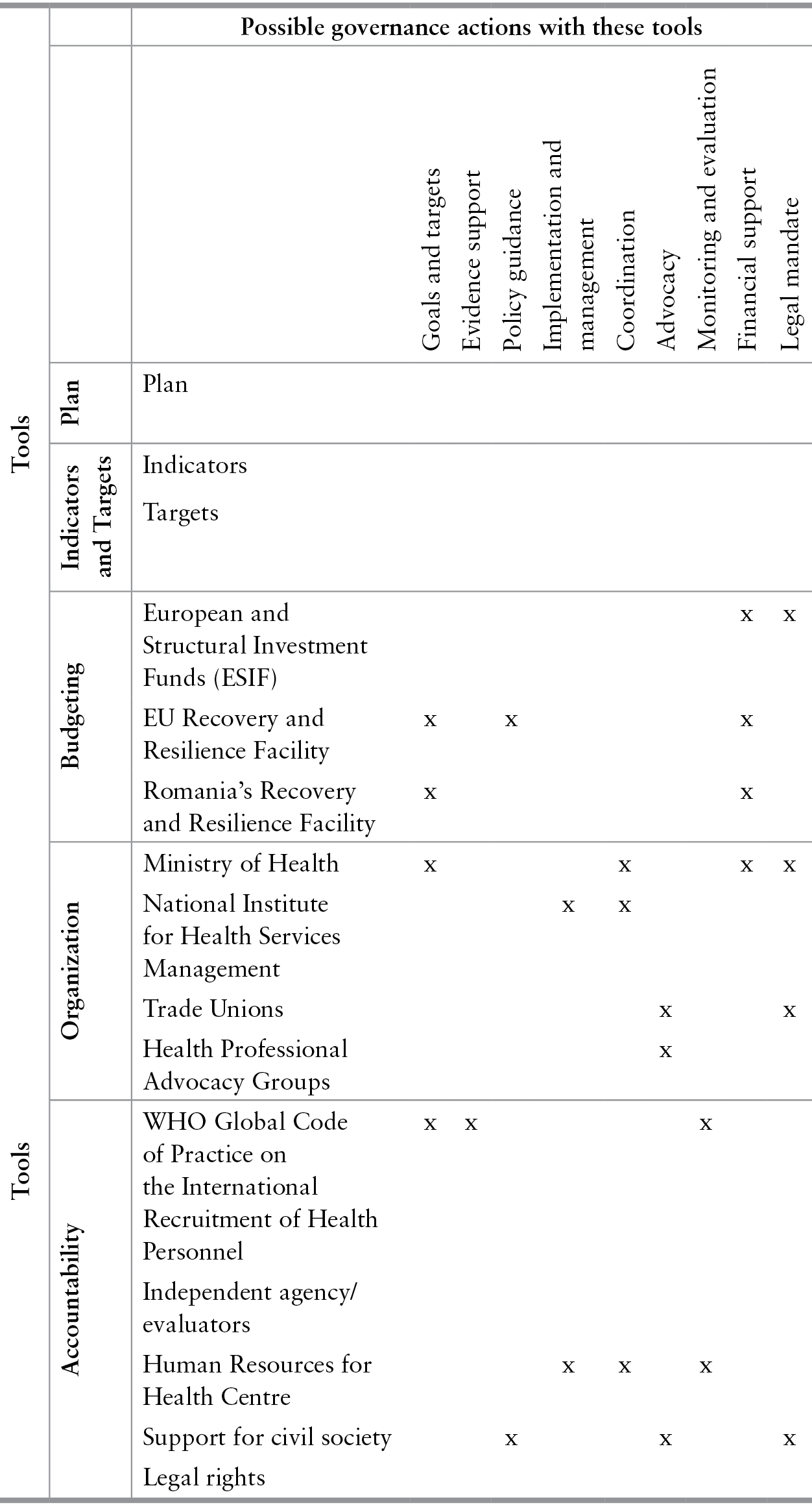

Ministerial linkages and stakeholder engagement across government ministries and with professional associations, trade unions and health professionals themselves have been key drivers of reforms at the national level (Table 8.2). Governance actions from the government and Ministry of Health have involved setting targets and goals, developing policies and strategies, and proving a legal mandate and financial support for reforms. In addition, advocacy from health professionals and their representatives has played a key role in driving actions around salary increases and improvements to working conditions. International cooperation and coordination among key stakeholders including the WHO, the EU and major destination countries, along with EU funding, have also been critical to tackling the international mobility of health workers.

Table 8.2 Governance actions and intersectoral structures driving health workforce reforms

| Possible governance actions with these tools | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tools | Goals and targets | Evidence support | Policy guidance | Implementation and management | Coordination | Advocacy | Monitoring and evaluation | Financial support | Legal mandate | ||

| Plan | Plan | ||||||||||

| Indicators and Targets | Indicators | ||||||||||

| Targets | |||||||||||

| Budgeting | European and Structural Investment Funds (ESIF) | x | x | ||||||||

| EU Recovery and Resilience Facility | x | x | x | ||||||||

| Romania’s Recovery and Resilience Facility | x | x | |||||||||

| Organization | Ministry of Health | x | x | x | x | ||||||

| National Institute for Health Services Management | x | x | |||||||||

| Trade Unions | x | x | |||||||||

| Health Professional Advocacy Groups | x | ||||||||||

| Accountability | WHO Global Code of Practice on the International Recruitment of Health Personnel | x | x | x | |||||||

| Independent agency/evaluators | |||||||||||

| Human Resources for Health Centre | x | x | x | ||||||||

| Support for civil society | x | x | x | ||||||||

| Legal rights | |||||||||||

8.5.5 Romania has implemented a wide range of actions to tackle HCWF issues, but more remains to be done

Romania has taken a number of steps to address health workforce deficiencies. These actions have contributed to the number of physicians and nurses per capita working in the public sector increasing by 29% and 24% respectively since 2007 (OECD.stat, 2021). However, the density of doctors and nurses still remains among the lowest in the EU, and tackling overall shortages, maldistribution and insufficient skillmix continues to be of high political importance.

The HCWF challenges faced by Romania are not unique and are being experienced by countries worldwide. These issues are likely to become more severe in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic, which has proved enormously challenging for health and care workers and led to a backlog of missed care in many countries (Reference van Ginneken, Reed and Sicilianivan Ginneken et al., 2022; Reference Williams, Maier and ScarpettiWilliams et al., 2022). Sustained action is therefore needed to strengthen the HCWF to ensure it can meet population health needs and respond to future emergencies. Improving salaries, working conditions, training opportunities and the development of competencies, along with joint workforce planning underpinned by better health workforce data, are some health policy areas that can contribute to meeting this aim and the objectives of SDG8 – decent work for all and economic growth.

8.6 Conclusion

Better health promotes better work and employment. Health policy itself can also promote better work and employment by improving health system standards and making health sector actors better employers. In many cases, these improvements involve redirecting or increasing health expenditure to improve the safety, quality and career progression of jobs at the lower ranks of the health system. Increasing public budgets can lead to political discourse when budgets already face constraints. However, if implemented well, changes in health expenditure can have benefits to the organization. A suggested solution includes paying an efficiency wage for better productivity rather than simply hiring at the lowest possible wage.

The governance mechanisms and tools are often already available in human resources policies and planning; thus, less innovation is required than is described in some other chapters of this book. Opportunities to improve workplaces are everywhere, from addressing certain management behaviours in particular units, to strong and well enforced antidiscrimination law, to paying a higher minimum wage, and schemes such as “Workers can be Allies”. But the political difficulty is that, outside a large influx of funds, improving the quality of jobs and reducing inequalities will impose costs on organizations (for safer work, for adapting hiring procedures to not discriminate) and reduce pay differentials that benefit higher paid workers. The benefits to organizations of high-quality jobs without discrimination have not always convinced managers and policymakers. Focusing attention on political actors such as unions and civil society that will support SDG8 is therefore crucial.